Rock art and the origins of art in Africa

The oldest scientifically-dated figurative rock art in Africa dates from around 26,000–28,000 years ago and is found in Namibia.

Between 1969 and 1972, German archaeologist, W.E. Wendt, researching in an area known locally as “Goachanas,” unearthed several painted slabs in a cave he named Apollo 11, after NASA’s successful moon landing mission.

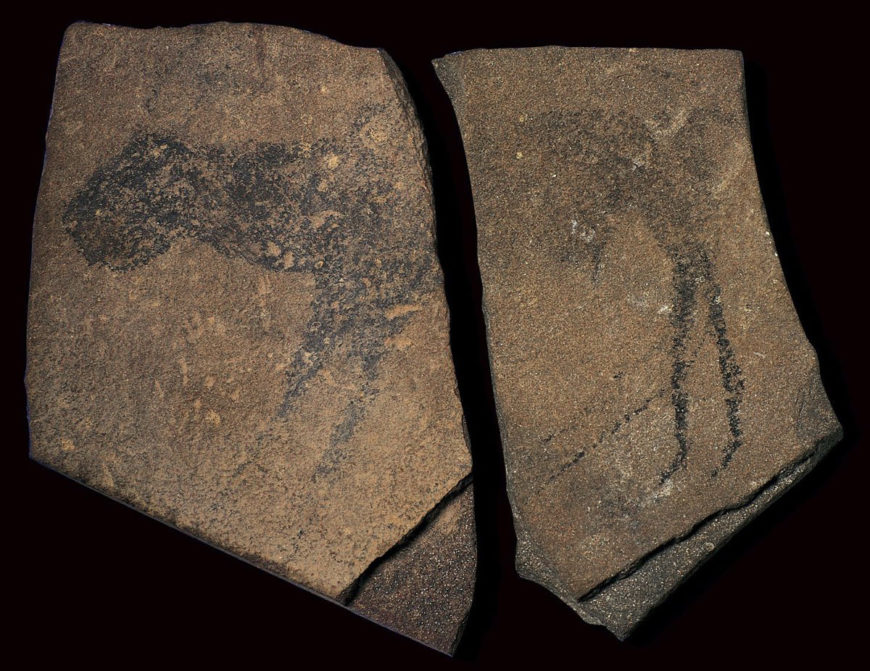

Seven painted stone slabs of brown-grey quartzite, depicting a variety of animals painted in charcoal, ochre and white, were located in a Middle Stone Age deposit (100,000–60,000 years ago). These images are not easily identifiable to species level, but have been interpreted variously as felines and/or bovids; one in particular has been observed to be either a zebra, giraffe or ostrich, demonstrating the ambiguous nature of the depictions.

Quartzite slabs depicting animals, Apollo 11 Cave, Namibia, c. 25,500–25,300 B.C.E. Image courtesy of State Museum of Namibia, Windhoek

Art and our modern mind

While the Apollo 11 plaques may be the oldest discovered representational art in Africa, this is not the beginning of the story of art. It is now well-established, through genetic and fossil evidence, that anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens sapiens) developed in Africa more than 100,000 years ago; of these, a small group left the Continent around 60,000–80,000 years ago and spread throughout the rest of the world.

Recently discovered examples of patterned stone, ochre and ostrich eggshell, as well as evidence of personal ornamentation emerging from Middle Stone Age Africa, have demonstrated that “art” is not only a much older phenomenon than previously thought, but that it has its roots in the African continent. Africa is where we share a common humanity.

The first examples of what we might term “art” in Africa, dating from between 100,000–60,000 years ago, emerge in two very distinct forms: personal adornment in the form of perforated seashells suspended on twine, and incised and engraved stone, ochre and ostrich eggshell. Despite some sites being 8,000 km and 40,000 years apart, an intriguing feature of the earliest art is that these first forays appear remarkably similar. It is worth noting here that the term “art” in this context is highly problematic, in that we cannot assume that humans living 100,000 years ago, or even 10,000 years ago, had a concept of art in the same way that we do, particularly in the modern Western sense. However, it remains a useful umbrella term for our purposes here.

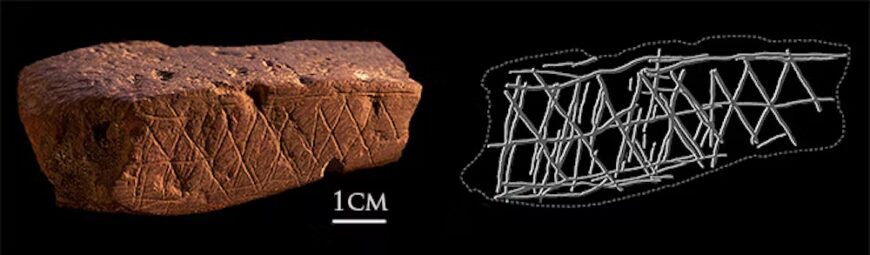

Incised ochre from Blombos Cave, South Africa. Photo by Chris. S. Henshilwood © Chris. S. Henshilwood

Pattern and design

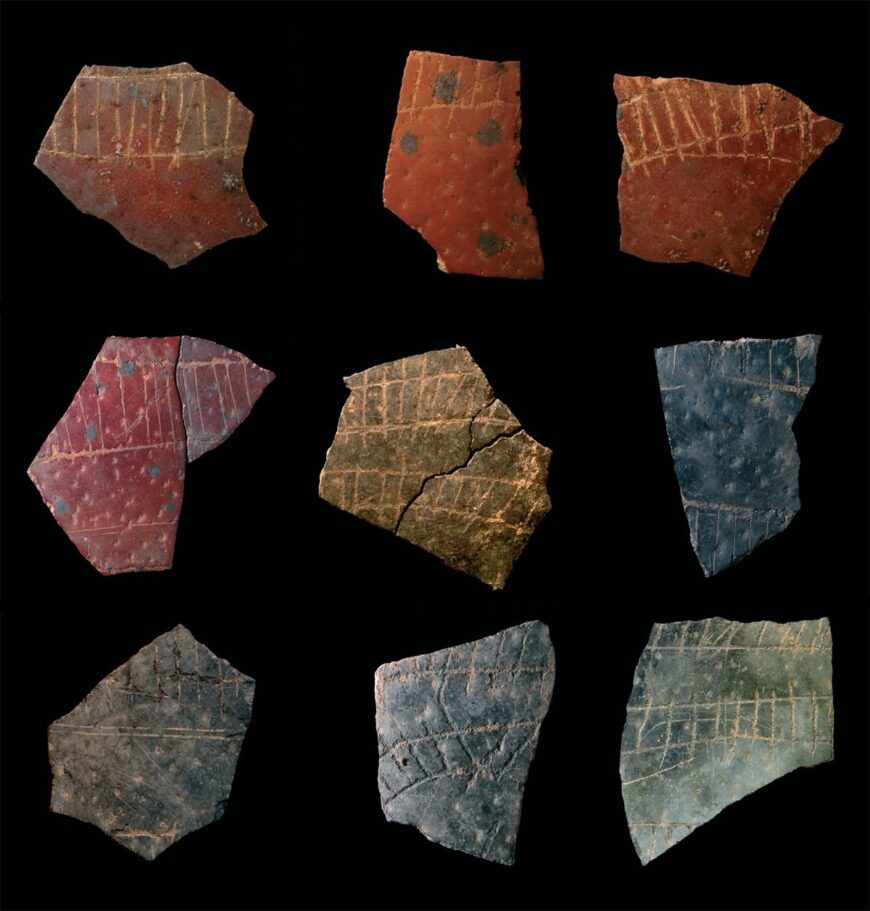

The practice of engraving or incising, which emerges around 12,000 years ago in Saharan rock art, has its antecedents much earlier, up to 100,000 years ago. Incised and engraved stone, bone, ochre and ostrich eggshell have been found at sites in southern Africa. These marked objects share features in the expression of design, exhibiting patterns that have been classified as cross-hatching.

One of the most iconic and well-publicised sites that have yielded cross-hatch incised patterning on ochre is Blombos Cave, on the southern Cape shore of South Africa. Of the more than 8,500 fragments of ochre deriving from the Middle Stone Age levels, 15 fragments show evidence of engraving. Two of these, dated to 77,000 years ago, have received the most attention for the design of cross-hatch pattern.

For many archaeologists, the incised pieces of ochre at Blombos are the most complex and best-formed evidence for early abstract representations, and are unequivocal evidence for symbolic thought and language. The debate about when we became a symbolic species and acquired fully syntactical language—what archaeologists term ‘modern human behaviour’—is both complex and contested. It has been proposed that these cross-hatch patterns are clear evidence of thinking symbolically, because the motifs are not representational and as such are culturally constructed and arbitrary. Moreover, in order for the meaning of this motif to be conveyed to others, language is a prerequisite.

The Blombos engravings are not isolated occurrences, since the presence of such designs occur at more than half a dozen other sites in South Africa, suggesting that this pattern is indeed important in some way, and not the result of idiosyncratic behaviour. It is worth noting, however, that for some scholars, the premise that the pattern is symbolic is not so certain. The patterns may indeed have a meaning, but it is how that meaning is associated, either by resemblance (iconic) or correlation (indexical), that is important for our understanding of human cognition.

Fragments of engraved ostrich eggshells from the Howiesons Poort of Diepkloof Rock Shelter, Western Cape, South Africa, dated to 60,000 BP. Courtesy of Jean-Pierre Texier, Diepkloof project. © Jean-Pierre Texier

Personal ornamentation and engraved designs are the earliest evidence of art in Africa, and are inextricably tied up with the development of human cognition. For tens of thousands of years, there has been not only a capacity for, but a motivation to adorn and to inscribe, to make visual that which is important. The interesting and pertinent issue in the context of this project is that the rock art we are cataloguing, describing and researching comes from a tradition that goes far back into African prehistory. The techniques and subject matter resonate over the millennia.

© Trustees of the British Museum