The mosque and cemetery of Sendang Duwur, located on a hilltop on the island of Java, was built in the 16th century. This was a time when the Javanese had begun to embrace Islam and Sendang Duwur represents one of the earliest extant Islamic complexes in Indonesia. The founder of the complex is believed to be Raden Nur Rahmat, a mytho-historical figure who is believed to have performed various miracles and later came to be referred to as Sunan (or Saint) Sendang. One of his miraculous acts was flying the original mosque from Mantingan to its current location in Lamongan, Java.

Map showing the location of the mosque and cemetery of Sendang Duwur, Lamongan, Java (underlying map © Google)

Although much of the original mosque no longer survives, vestiges of the tomb of Sunan Sendang and its stone entrances remind visitors of the transculturation between Hindu, Buddhist, and Islamic arts from Java.

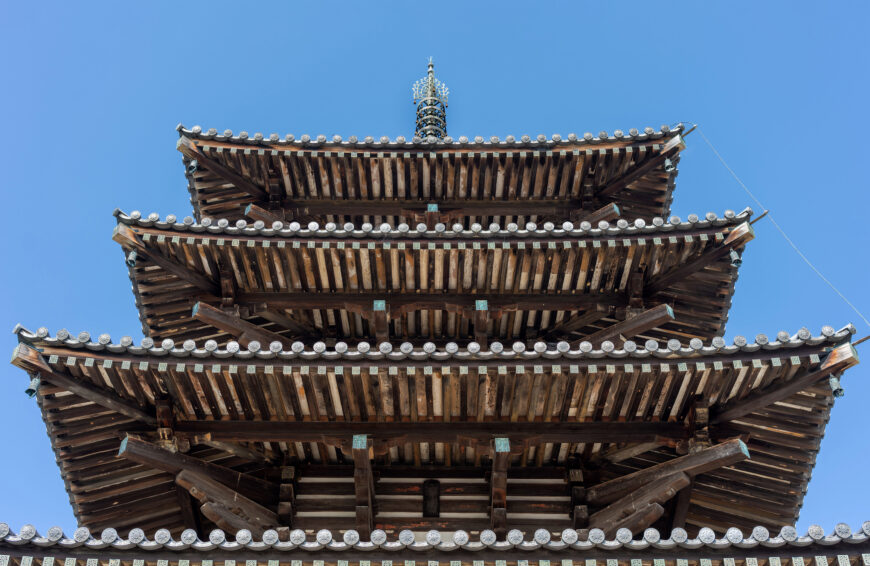

Prior to the 15th century, Hinduism and Buddhism were among the primary religions on the island. Evidence of Hindu and Buddhist art and architecture dates to at least the 5th century C.E. When Islam was adopted in Java, its monuments were influenced by the visual vocabularies of Hinduism and Buddhism. For example, the impressive, winged gate at Sendang Duwur (image below) is often thought to be inspired by the figure of the Hindu bird, Garuda. Meanwhile, the architectural style of split gateways at Sendang Duwur has its origin in the earlier Hindu-Buddhist kingdom of Majapahit.

Floral ornament on the wall of Sendang Duwur, Java, which is ubiquitous in earlier Hindu temples in Java, c. 16th century (photo: Panggah Ardiyansyah, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Islam in Java

In local tradition, the Islamization of Java has been attributed to several quasi-mythical figures from various regions on the island’s northern coast. Though these figures are now popularly known in multiple localized oral histories as Wali Sanga (Nine Saints) and assumed to have lived between the 15th and 16th centuries, James J. Fox, a scholar of Islam, has noted that the list was largely developed in the 19th century. [1]

Sendang Duwur, in the town of Lamongan, is located on the east side of Java’s northern coast. This geographical position is important to the history of Islam in Java because it is located near the estuary of the Brantas River, which facilitated access to the island’s interior and to those who had power and influence to adopt Islam and build mosques. It has been suggested that Muslim communities enjoyed a higher social status due to their wealth and influence in trading which helped to facilitate marriages into royal families, and that this, in turn, spurred the genesis of Islamic polities on the islands as well as the proliferation of art and architecture related to the faith. [2]

Map of Java Island showing related locations in the north coast of Java (illustration: Rizal Yoga Prayoga)

Archeological and historical evidence related to Sendang Duwur provides important insights into the ways in which Islamic practices were embraced and localized in Java. As one of the oldest Islamic monuments in Java, its architecture proves that earlier Hindu-Buddhist traditions seamlessly transitioned into newer Islamic practices. [3]

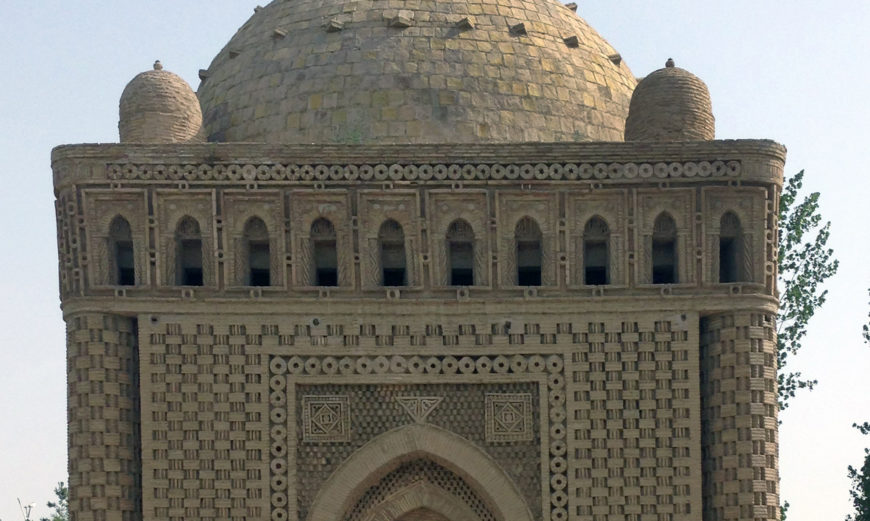

The cemetery

The cemetery at Sendang can be essentially divided into two parts. The front part, including the tomb house of Sunan Sendang, has been preserved as an archaeological site. Meanwhile, the other part, behind the tomb house, is still being actively used as a cemetery by the local villagers. Entering the cemetery at Sendang Duwur, visitors and pilgrims are greeted by a split gateway. It is as if a gateway was split into two parts to create a passage in between.

Split gateway at the entrance of Sendang Duwur’s cemetery, Java, 16th century (photo: Panggah Ardiyansyah, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The passage is equipped with a flight of stairs to allow entry into a more sacred space. The gateway has no roof, and the inner sides are left undecorated as is typical. It is not a standalone structure and is connected to a wall on its right and left.

Wringin Lawang Gate at Trowulan, Java, c. 14th century, around 72 km south of Sendang Duwur (photo: Panggah Ardiyansyah, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

This architectural style has been in use since the earlier, pre-Islamic Majapahit period as can be seen with the Wringin Lawang Gate, one of the surviving giant gateways into Trowulan, the capital of Majapahit. It is notable that split gateway architecture (at a smaller scale compared to the Majapahit gate) is readily found not only at Sendang Duwur but also in later Islamic cemeteries, mosques, and palaces in Java.

The tomb house of Sunan Sendang is distinguished by a monumental stone gateway. It is the most preserved and intact structure of the original 16th-century monument. On the lower centre part of the gateway’s roof is the head of kala, a mythical figure tasked to guard time. While its lower jaw has been replaced with new uncarved stones, two bulging eyes of the kala can still be seen under fiery, or rather, floral hair. Kala images are often found in Hindu and Buddhist temple’s gates. The Sendang Duwur gateway is decorated with two large wings on either side of the doorways. The wings are long and spread out, with the wingspan measuring roughly five meters. The upper feathers of the wings have been carved in an upward tilt to indicate flight, perhaps making reference to Sunan Sendang’s powers and the origin story of the mosque. However, winged imagery is commonly seen in both Hindu and Islamic art.

Some scholars have argued that the wings are a representation of Garuda, a hybrid avian-human figure who serves as the celestial mount of the Hindu god Vishnu. Instead, it is likely that the adoption of winged imagery was an adaptation of existing Hindu visual vocabularies for an Islamic context. The wings came to be associated with Buraq, a mythical winged horse (sometimes depicted with human heads) who is the celestial mount for the Prophet Muhammad’s ascent to Heaven. The winged gateway can be seen as a symbolic means to transport pilgrims into a more sacred space both figuratively and literally as they enter the tomb of Sunan Sendang.

Entrance to the mosque at Sendang Duwur, Java, c. early 20th century, the upper stone boulders, with darker materials and rectangle shape, appear to be an original structure from the 16th century (photo: Panggah Ardiyansyah, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The mosque

In contrast with the cemetery compound, local villagers renovated the mosque building in 1920, which was memorialized through a series of multi-lingual inscriptions (using Javanese, Arabic, and Roman scripts) installed in the front doors. A wealthy kyai (Islamic religious leader) from a nearby village is believed to have ordered and financed the renovation in the early 20th century. During this renovation, most parts of the mosque were replaced with new materials except for structural wooden beams and stone boulders. This information was written in an Arabic inscription currently placed on the portico. Below this Arabic inscription is a Modern Javanese inscription presenting the chronogram of 1561 C.E., the year when the mosque originally founded.

A stylized kala makara of minbar arch, in which the kala head figure has been reconfigured into a radiating circle shape containing eye, nose, and mouth, at Sendang Duwur, Java, c. 16th century (photo: Panggah Ardiyansyah, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The mosque’s main hall is square, with four pillars supporting the roof structure. This four-pillar architecture is quite common in Javanese mosques. A small chamber extends from the hall’s western wall. This small chamber functions as a mihrab, where the imam positions himself to lead a prayer. In Java, the Kaaba, to which Islamic prayers are facing, is to the west, hence the mihrab’s position. Also, inside the mihrab is a wooden minbar, a platform with a flight of steps and a chair where the preacher would speak during Friday prayer. This minbar is decorated with an arch. Both ends of the arch are shaped like curl that is intended to symbolize makara, which is known as the vehicle of the god of the ocean, Varuna, in Hindu mythology. At the center of this arch is a circle with rays containing a stylized eye, nose, and mouth. Such an artistic arrangement gives the impression of a kala image. Consequently, this iconographic combination reminds us of kala-makara decoration found in the Hindu and Buddhist temples in Java.

Pilgrimage in Java

Today the complex—or more precisely the grave of saint Sunan Sendang, sheltered inside the tomb house—is a popular destination for Muslim pilgrims. Pilgrims worship at the holy grave hoping for spiritual guidance and blessing. Water, collected from the springs at the complex, is considered sacred and is often taken home in bottles sold by the site caretakers. This sacred water is believed to distribute saintly blessings for the pilgrims against misfortune. It is also said that men with political ambitions shower with water from the well at midnight to accumulate blessings for a successful campaign in local elections.

Pilgrimage to Sendang Duwur is part of wider local tradition in Java. The graves of Islamic saints have been attracted thousands of visitors to such sites, particularly on auspicious days such as the Islamic New Year’s Eve. Like Sendang Duwur, these graves are also located on hills or mountain tops, reflecting on a longstanding belief between sacrality and nature.