St. Michael defeats the devil in Renaissance Spain

[0:00] [music]

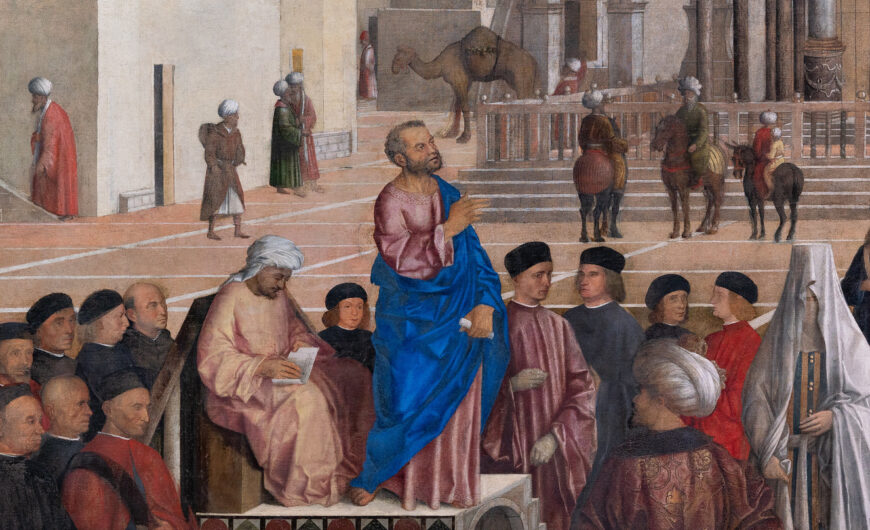

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:01] We’re in the Cloisters, part of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, looking at a large panel painting by an artist who goes by the name the Master of Belmonte. We use that term “master” when we can’t identify the individual artist.

Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank: [0:19] The Master of Belmonte is from Aragon, in Spain, in the 15th century. The painting we’re looking at here depicts Saint Michael the Archangel as he spears the devil.

Dr. Zucker: [0:30] What a devil that is. We often see Saint Michael in Last Judgment scenes, often holding the scales that weigh the blessed and the damned to determine who goes to heaven and who goes to hell. But he’s also commonly shown defeating evil.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [0:45] When he’s shown in this way, he’s often dressed in armor, which he is here. He’s dressed in fabulous armor, and he is standing on top of the devil. It is symbolic of the Church Militant, this idea of the church triumphant over sin, over the devil.

Dr. Zucker: [0:59] But here, the artist has been really playful. The devil is awful. He’s disgusting. He’s really vile, but he’s also almost comical.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [1:08] Instead of showing an individual body of the devil, we have a figure that is made up of all these different composite creatures and demons, and they’re biting each other and forming this anthropomorphized demon.

[1:19] We see bird heads that are twisting here and there. We see bird talons. We see what look like dog heads. We see reptilian creatures biting the arms of a body. We see all these different faces across this figure, and then what I can only describe as the hair, that looks like some Dr. Seuss figure.

Dr. Zucker: [1:36] Particularly disgusting, for me, are the frog and the snake that are coming out of the ear, and of course the insects that are crawling all over him.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [1:44] We see the tail of this creature is formed of a bird head, and it’s eating an insect in its mouth. We see all these scaly reptilian creatures that were associated with evil, that were associated with the devil.

Dr. Zucker: [1:56] It’s interesting that although there’s a spear going through the devil’s mouth, the devil is actually in a comfortable repose, as if the devil is on the beach.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [2:05] The devil’s here on the ground reclining, whereas Saint Michael is standing atop him looking very regal, very composed.

[2:13] He is standing in chain mail and he holds a shield. His sword is around his waist. He’s holding the spear in his right hand. His left hand is holding a shield, and his beautiful wings are spread out behind him, moving forward as if to envelop him.

Dr. Zucker: [2:29] The artist has really lavished attention and detail on Michael. Look at the peacock feathers that make up those wings. When the painting was new and bright, it must have been absolutely spectacular.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [2:41] Then there’s the other wings that are different colors. We see lime greens, and light pink, and golden hues. And not to be outdone is the remainder of the painting. The Master of Belmonte really did spare no expense in terms of details. It is a true feast for the eyes.

Dr. Zucker: [2:57] We see that in the tiles on the floor, where we seem to see references to Islamic tiles, tiles that were common in Spain at this time.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [3:04] The Master of Belmonte is a Spanish artist, but we see a lot of characteristics that we typically identify with Netherlandish or Flemish painting, and that’s because, in the 15th century, you have a lot of artists who are adapting and using Flemish painting techniques and characteristics.

[3:21] For instance, we see the close attention to details, the attention to different textures. We see the use of oil painting. This painting is actually a combination of both tempera and oil painting, but the use of oil painting with different glazes to build up a richer color palette.

[3:36] We really see that spectacularly here in the cape that Saint Michael is wearing, where he’s wearing this blue cape and the inside is this brilliant deep red.

Dr. Zucker: [3:45] I want to go back to a word you used just a moment ago, which was texture, because this is not a flat painting. The artist actually built up in gesso sections of this to create a sculptural quality, as if this was relief carving.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [3:57] In art history, we tend to call this pastiglia, which is an Italian word that denotes when an artist has built up these three-dimensional qualities on the painted surface. As we get closer to the painting and you see the light shining on it, it really does add this intensity to the painting where it really does seem like this figure is about to walk off the two-dimensional surface into your space.

Dr. Zucker: [4:18] It’s important to remember that we should not be seeing this painting in a museum. This was intended to be seen in a church environment. It would have been lit by light that was filtering in through windows high up on the wall, by candles, and by oil lanterns. And of course the flames would flicker and would dance across the surface, enlivening this figure.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [4:37] And much of the surfaces here that are done in gesso, in relief, are ones that are gilded or in silver. And so they’re associated with more luxury, but they would have reflected that light more brightly. I want to go back to something you said, which is that we would have seen this in a church. This painting is actually just a small portion of what would have been a much larger altarpiece.

Dr. Zucker: [4:56] A polyptych with numerous scenes that probably would have represented numerous scenes and many different saints.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [5:03] Because it’s in a church, you expect to see saints and other types of symbols and motifs that would accentuate their holiness, and we see that in this painting. If we look behind Saint Michael, for instance, we can make out that there is this beautiful brocade that’s hanging behind him.

[5:18] You can make out the blue-and-white striped wall on top of which the brocade is hanging. It not only accentuates the importance of Saint Michael here, but it adds even greater surface texture to this painting.

Dr. Zucker: [5:32] That brocade is magnificent. In it we can recognize a fairly standard motif, which is known as the pomegranate-and-thistle motif. The lavishness of this brocade would have been associated with the cultures of the eastern Mediterranean.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [5:45] This is not only a design that’s taken from Islamic textiles, but we also have to remember that in Spain you have a long and rich history of the three faiths, where you have Islam, Judaism, and Christianity all comingling with one another. To some degree, we’re seeing that encapsulated in this painting: the tiles on the floor that are likely derived from Islamic tiles, that brocade that is paying attention to Islamic brocade designs.

Dr. Zucker: [6:10] Although the reuse of Islamic motifs was seen as benign within, for example, that brocade or the tilework, this was the height of the Reconquest of Christianity over Islam in Spain. Seeing Saint Michael defeating the devil here certainly would have been seen in parallel to the Christian triumph over Islam in Spain.

[6:32] [music]

| Title | Saint Michael Defeating the Devil |

| Artist(s) | Master of Belmonte |

| Dates | 1450–1500 |

| Places | Europe / Southern Europe / Spain |

| Period, Culture, Style | Renaissance / Spanish and Portuguese Renaissance |

| Artwork Type | Painting |

| Material | Oil paint, Tempera paint, Panel |

| Technique |

Read about this painting on The Metropolitan Museum of Art‘s website

Alberto Velasco González, Virgin and Child with Musician Angels. The Master of Belmonte and Late Gothic Aragonese Painting (Jaime Eguiguren, 2017)

Loading Flickr images...

Take notes while watching the video, using the Master of Belmonte’s St. Michael Defeating the Devil active note-taking activity.

Read more about 15-century Spanish painting

Read more about the Renaissance in Spain