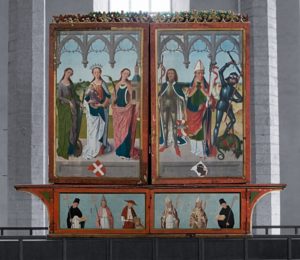

Hermen Rode, Saints Nicholas and Victor Altarpiece (second opening), 1478–1481, 632 x 348 cm (Art Museum of Estonia, Tallinn; photo: Anton Skrobotov, by permission)

Tapas and Tallinn

Commissioning an altarpiece (a work of art placed on top or beside an altar to aid in Christian devotional worship) in the 15th century was a lot like going out to a tapas restaurant with a bunch of friends. The group talks about the menu, consults with the server, orders several dishes, and after the kitchen prepares the meal, each dish is brought to the table to be shared by everyone. Sure, the final bill is expensive, but everyone chips in. You may even have that one friend who is particularly skilled at divvying up the bill, so each friend pays his or her fair share. In this way, the total shared experience is greater than the sum of its parts by virtue of the fact that everyone has contributed.

Nave of the Church of St. Nicholas, with a view toward the Saints Nicholas and Victor Altarpiece, Tallinn, Estonia (photo: JoJan, CC BY 4.0)

This experience of collective participation extends to the Saints Nicholas and Victor Altarpiece in Tallinn’s Church of St. Nicholas, home of the city’s elite and wealthiest merchants. Today, Tallinn is the capital of the Republic of Estonia, although the city was known in the Middle Ages by its German name, Reval. It was one of the largest cities in the historic region called Livonia, which comprises modern-day Estonia and Latvia. Situated on the coast of the Baltic Sea, Tallinn played a vital role in sea trade in the Middle Ages, distributing raw materials to western European markets.

In August 1481, the altarpiece was set up on the church’s high altar as an emblem of collective effort and enterprise. Members of the congregation, along with two local groups—the Great Guild and the Brotherhood of the Black Heads—pooled their resources to bring the altarpiece to Tallinn. They ordered and transported this enormous wooden object from the workshop of Hermen Rode in Lübeck, Germany, approximately 1,100 kilometers (684 miles) away by sea. In the last decades of the fifteenth century, Lübeck workshops prolifically produced painted wooden sculpture and retables (altarpieces) for audiences across the Baltic and North Seas. Rode, and his main contemporary competitor, Bernt Notke, maintained large-scale workshops capable of handling a variety of commissions, including those sent to distant cities.

The altarpiece cost 1,250 Riga marks—an equivalent amount to the cost of two stone houses or a new ship. This was a high price and covered the fine quality and large size of the altarpiece, as well as the added expense in arranging its long-distance transport. Today it remains one of the largest altarpieces in northern Europe, measuring 6 meters wide and 3.5 meters tall (more than 11 feet tall and 20 feet across).

Final view completely open, Hermen Rode, Saints Nicholas and Victor Altarpiece , 1478–1481 (Art Museum of Estonia, Tallinn)

Three Different Views

Many altarpieces have hinged wings that can open and close like doors. This altarpiece is double-winged, meaning it has two sets of doors, a hallmark feature of North German carved and painted retables (though double winged altarpieces are known elsewhere). The two sets of doors offer three distinct views: closed, the first opening with painted scenes, and the final view with carved and painted sculpture. The large-scale multimedia format across three views lends itself to displaying a high number of iconographic scenes. The altarpiece features 40 saints that resonated with the merchants of Tallinn.

View from rear of the left panel of the altarpiece that can be viewed when fully closed showing the Virgin Mary in the center, Hermen Rode, Sts. Nicholas and Victor Altarpiece, 1478–1481 (Art Museum of Estonia; photo: Anton Skrobotov, by permission)

Six standing saints, closed view, Hermen Rode, Sts. Nicholas and Victor Altarpiece, 1478–1481 (Art Museum of Estonia, Tallinn)

When the altarpiece is closed, the painted wings are decorated for daily devotional use. The two main painted panels visible when the altarpiece is closed shows six saints standing on a stone platform. From left to right they are: St. Catherine, the Virgin Mary holding the Christ Child, St. Barbara, St. Victor of Marseilles, St. Nicholas, and St. George. These six saints reflect the devotional needs of the congregation at Tallinn’s Saint Nicholas Church. For instance, the Virgin Mary served as the patron saint of Livonia, St. Victor of Marseilles was the patron saint of Tallinn, and St. Nicholas, the patron saint of sailors and merchants, was also the namesake of the church and the high altar.

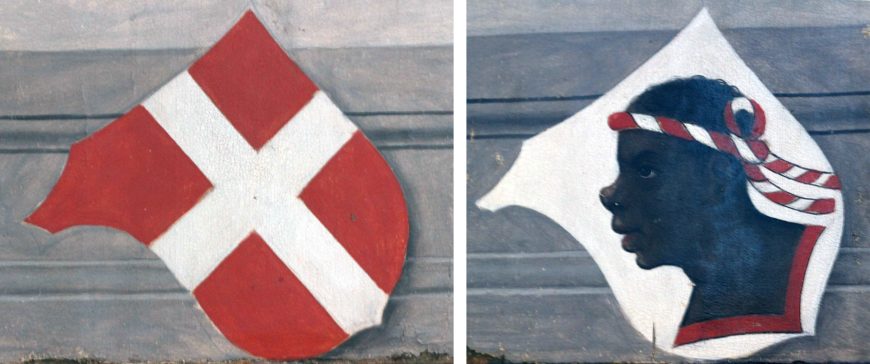

Emblems (Coats of Arms) of the Great Guild and the Brotherhood of the Black Heads (featuring St Maurice). Hermen Rode, Sts. Nicholas and Victor Altarpiece (closed), 1478–1481 (Art Museum of Estonia, Tallinn; photo: Laura Tillery)

Group patronage

The emblems of the Great Guild and the Brotherhood of the Black Heads are prominently painted below the saints on the front of the altarpiece. Both the Great Guild and the Brotherhood of the Black Heads worked together to finance, transport, and install the altarpiece.

The left wing features the red and white coat of arms of the Great Guild that was also the coat of arms of the city of Tallinn. The right wing contains a coat of arms with the profile of St. Maurice, who served as one of the patron saints of the Brotherhood of the Black Heads. St. Maurice, a black Roman soldier martyred in the early Christian period, was venerated as a warrior saint since the seventh century. The Brotherhood of the Black Heads celebrated warrior saints, including Sts. George and Victor, likely due to the long history of crusades in the eastern Baltic Sea region. Both groups’ emblems are repeated multiple times throughout the altarpiece program. Such an explicit marker could serve as a reminder of their generous donation as well as ensure the salvation of the groups’ members.

St. Nicholas saving seamen aboard a cog ship (detail), Sts. Nicholas and Victor Altarpiece (first opening), 1478–1481 (Art Museum of Estonia, Tallinn)

Protection at sea

The name of the altarpiece (the Saints Nicholas and Victor Altarpiece) stems from the collection of sixteen scenes that depict the lives of the local patron saints Nicholas and Victor that are visible when the first set of doors are open. Two painted scenes in particular would have been familiar to the mercantile audience of Tallinn.

In a scene from the life of St. Nicholas (the patron saint of sailors and merchants), the saint miraculously saves the seamen aboard a cog ship during a storm (note the ship’s broken mast). Barrels of goods are being thrown into the sea in a desperate effort to save the ship.

A cog ship was the primary seafaring vessel for merchants in the Hanse, also known as the Hanseatic League (a trade coalition made up of German-speaking merchants and cities in the late Middle Ages with established routes across the Baltic and North Seas). At the front of the cog hang four flags, marked with the coats of arms of the Brotherhood of the Black Heads and the Great Guild. In fact, many members of both the Brotherhood of the Black Heads and the Great Guild were also merchants within the Hanse trade organization. The comfort provided by St. Nicholas must have been powerful for the merchants, whose livelihood depended on shipping trade across the often rough seas.

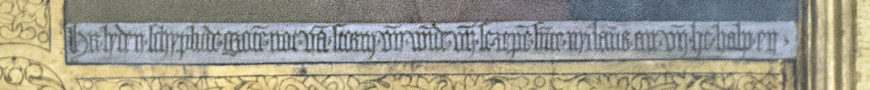

Inscription in Middle Low German. Hermen Rode, detail of St. Nicholas, Sts. Nicholas and Victor Altarpiece (first opening), 1478–81, Tallinn (Art Museum of Estonia; photo: Ad Meskens, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The inscription below the image reads “Here the shipmen suffered greatly from the storm and wind; they invoked Saint Nicholas and he helped them.” It is written in Middle Low German, the shared language of Hanse merchants. Tallinn provided raw materials such as honey, fur, and amber to the northern European markets through the Hanse. Hanse merchants traveled widely across the Baltic and North Seas, with direct trade routes connecting Tallinn (Estonia) to Bergen (Norway), Bruges (Belgium), and London (England) via Lübeck (Germany).

Hermen Rode, Death of St. Victor, Sts. Nicholas and Victor Altarpiece (first opening), 1478–1481, Tallinn (Art Museum of Estonia, public domain)

In the scene of the death of St. Victor, the skyline of church pinnacles and civic monuments in the background would have been familiar as the 15th century city of Lübeck, the leading city in the Hanse. The central geographic location of Lübeck between the Baltic and North Seas determined its vital position in Hanse trade: nearly every product from Tallinn traveled through Lübeck before entering other western European markets. The merchants of Tallinn, including members of the Brotherhood of the Black Heads and the Great Guild would certainly have been able to recognize Lübeck’s iconic skyline of seven churches and built fortifications.

There are varying interpretations as to why the Lübeck city view serves as the background to the beheading scene of St. Victor. Did Hermen Rode add the city view as a kind of signature, marking its place of manufacture? Or did the Great Guild and Brotherhood of the Black Heads request the inclusion of Lübeck to promote Tallinn’s vital position in the Baltic Sea trade economy? While we may never certainly know why the city view of Lübeck is included on this altarpiece, we can be sure that the painted scenes in the second view would have guided devotion for protection at sea.

Hermen Rode, Sts. Nicholas and Victor Altarpiece (open), 1478–1481, Tallinn (Art Museum of Estonia; photo: WanderingTrad, CC BY-SA 4.0)

After opening the second set of painted doors, the final view reveals two rows of 30 carved and painted standing saints (some of the original sculpture has been replaced). This interior view was rarely shown—it was reserved only for the most holy days according to the Christian liturgical calendar. The assemblage of individual saints, each set in intricate Late Gothic niches, work together to create a dramatic view.

Like Tallinn’s mercantile collective, the overall experience is greater than the sum of its parts. Today, the Saints Nicholas and Victor Altarpiece stands as a rare example of a high altarpiece that remains in its original location since its installation in 1481.

Additional Resources:

Merike Kurisoo – The Retable of the High Altar of St Nicholas’ Church in Tallinn. Workshop of the Lübeck Master Hermen Rode. 1478–1481. Art Museum of Estonia

The Retable of the High Altar of St. Nicholas’ Church. Art Museum of Estonia, Niguliste Museum

Hilkka Hiiop and Merike Kurisoo (eds.), Rode Altarpiece in Close-Up. History, Technical Investigation and Conservation of the Retable of the High Altar of Tallinn’s St. Nicholas’ Church (2013-2016) (Tallinn: Eesti Kunstikadeemia, 2016).

Anu Mänd, “Black Soldier-Patron Saint: St. Maurice and the Livonian Merchants,” Nordic Review of Iconography 1 (2014), pp. 57–75.

Anu Mänd, “The City of Tallinn (Reval) in the Late Middle Ages and the Renaissance, ” in Michel Sittow: Estonian Painter at the Courts of Renaissance Europe, ed. John Oliver Hand and Greta Koppel, exhibition catalogue, National Gallery of Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017), pp. 19–25.

Anu Mänd, “Symbols That Bind Communities: The Tallinn Altarpieces of Rode and Notke as Expressions of the Local Saints’ Cult,” in Art, Cult, and Patronage: die Visuelle Kultur im Ostseeraum zur Zeit Bernt Notkes, edited by Anu Mänd and Uwe Albrecht (Kiel: Ludwig, 2013), pp. 119-141.

Anje Rasche, Studien zu Hermen Rode (Petersberg: Michael Imhof Verlag, 2013).

Laura Tillery, “Hanse Cultural Geography and Communal Identity in Late-Medieval City Views of Lübeck,” Journal of Urban History (May 2020) https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0096144220917933