Luca Signorelli, The Damned Cast into Hell, 1499-1504, fresco, 23′ wide (San Brizio chapel, Orvieto Cathedral, Orvieto, Italy) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Imagine being confronted by this scene—men and women screaming, their nude bodies contorted in pain as they are tortured by garishly colored demons.

Naked men and women screaming while being attacked by demons (detail), Luca Signorelli, The Damned Cast into Hell, 1499-1504, fresco, 23′ wide (San Brizio chapel, Orvieto Cathedral, Orvieto, Italy) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Off to the side, a fiery pit awaits these unfortunate souls. Fragmented bodies of those already consigned to the flames are visible through the acrid smoke.

Three archangels, Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael, clad in armor, observe as humans and demons tumble through the sky (detail), Luca Signorelli, The Damned Cast into Hell, 1499-1504, fresco, 23′ wide (San Brizio chapel, Orvieto Cathedral, Orvieto, Italy) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Above, demons and humans tumble through the sky. Standing next to them on small clouds are the three archangels, Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael, fully clad in suits of armors, drawing the swords at their sides. Although you might be wondering, what on earth is going on here—to a fifteenth century viewer it would have been quite obvious.

Left: Façade of Orvieto Cathedral, Orvieto, Italy; Right: view into the San Brizio Chapel in the Orvieto Cathedral (photos: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Painted by Luca Signorelli from 1499 to 1503 in the San Brizio Chapel in the Cathedral in Orvieto, Italy, the fresco represents one part of the End of Days narrative, when Christ returns to judge mankind—and to separate those who will go to heaven (the blessed) from those who will go to hell (the damned). An account of this event is found in the Gospel of Matthew (25:31-46), which reads in part:

But when the Son of Man comes in his glory, and all the holy angels with him, then he will sit on the throne of his glory. Before him all the nations will be gathered, and he will separate them one from another, as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats. He will set the sheep on his right hand, but the goats on the left; Then the King will tell those on his right hand, ‘Come, blessed of my Father, inherit the Kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world… Then he will say also to those on the left hand, ‘Depart from me, you cursed, into the eternal fire which is prepared for the devil and his angels;…These will go away into eternal punishment, but the righteous into eternal life.

In this passage the sheep are the faithful who have followed Christ in a sin-free life and the goats were those who did not. This subject was a popular visual means of illustrating the rewards and punishments that awaited the lay person at the end of time. It was most often depicted in a single composition, such as in Giotto’s Last Judgment fresco in the Arena Chapel.

Giotto, Last Judgment, c. 1305, fresco, 1000 x 840 cm (Arena Chapel, Padua, Italy) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Here we see Christ enthroned in the top center, flanked by the Apostles on either side. In the lower portion of the composition are representations of the two sides—the “sheep” and the “goats.” On Christ’s right hand side (the left side of the viewer) are the Elect, those who have been chosen to go to Heaven, some of whom are still emerging from their tombs, while on his left hand side, we see the Damned, those who have been consigned to the fiery pits of Hell and are being tortured by demons. Giotto’s Last Judgment was placed over the door into the chapel, thus providing visitors who were leaving a clear visual message.

Left: Inside the San Brizio Chapel; Right: The damned being carried across the river to the underworld (detail), Luca Signorelli, The Damned Cast into Hell, 1499-1504, fresco, 23′ wide (San Brizio chapel, Orvieto Cathedral, Orvieto, Italy) (photos: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In the case of the San Brizio Chapel, the entire chapel was used to represent this subject, not just one wall, and this was a rather unique situation. The subject was divided into six large, individual scenes including The Elect being called to Heaven, the Resurrection, the Deeds of the Antichrist and the Apocalypse. The Damned is located next to the altar wall—where we see another fresco, those consigned to Hell being carried across the river to the underworld (above).

Humans being tortured by demons in the foreground (detail), Luca Signorelli, The Damned Cast into Hell, 1499-1504, fresco, 23′ wide (San Brizio chapel, Orvieto Cathedral, Orvieto, Italy) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

One of the most striking aspects of Signorelli’s fresco is his representation of the nude figure. In fact, the Damned, along with its companion scene of the Elect (directly across the chapel on the opposite wall) seem to have been a means for Signorelli to explore the multitude of attitudes and positions possible in the human body. In the Damned, the brightly colored demons are pushing, pulling, tying up, and exacting all manner of physical torture on the sinners whose bodies are equally contorted, struggling to break free. The figures are all quite muscular, even hyper-muscular in some cases.

The interest artists had during this period in the study of the human figure was certainly driven, at least in part, by their interest in the classical past. As the Renaissance is the period of the “rebirth” of classical antiquity, artists looked to those exemplars of the past as ideals. For example the contropposto stance of the famous Doryphorus statue from Greece influenced most painters and sculptors of the period. There was also a general desire to understand the workings of the human body, and we can definitely perceive such interest in other similar works.

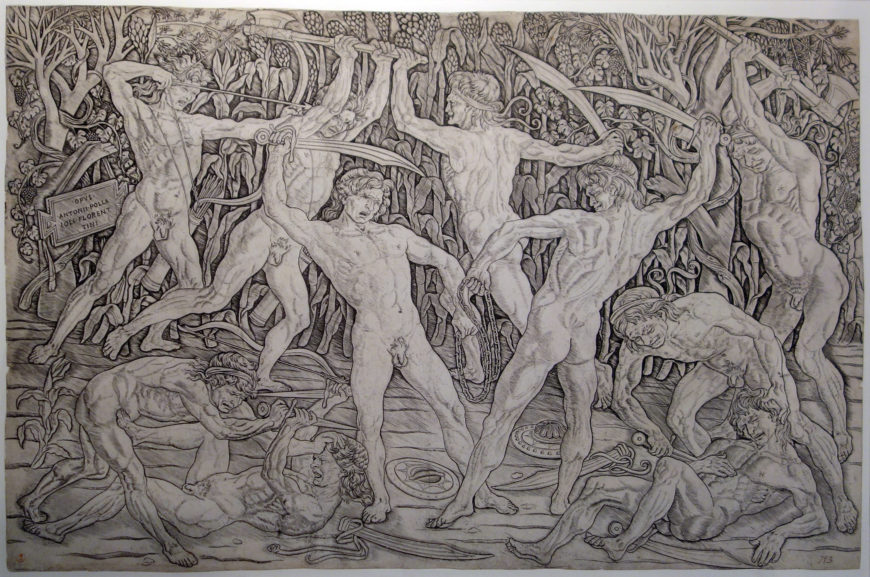

Antonio Pollaiuolo, Battle of the Nudes, c. 1470-95, engraving, 41.6 x 59.4 cm (The British Museum) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

For example, Antonio Pollaiuolo’s large engraving, The Battle of the Nudes, is one of the most important works of the period. In it, Pollaiuolo shows ten nude, male figures battling each other in a fantastical landscape. Notice the two men in the foreground are in the same pose, but reversed. This way Pollaiuolo could show both the front and back side of the same position. The other figures in the background assume equally exaggerated poses and dynamic movements, illustrating the flexing of muscles as the body engages in battle. This if very much in line with what Signorelli achieved in his fresco.

Aristotele da Sangalla, Battle of Cascina (after a lost Michelangelo), 1504-06, oil on panel (Holkham Hall, England)

Perhaps the artist most associated with the study of the male nude figure is Michelangelo and it has been suggested by scholars that he may have been influenced by Signorelli’s figures in some of his works. And indeed shortly after the completion of the San Brizio chapel, Michelangelo produced one of the most influential works of the period, The Battle of Cascina, 1504-06. In this large scale cartoon (a preparatory design for a fresco), which only survives in copies, we see many of the same interests as in Signorelli’s Damned. Michelangelo presented figures from a variety of different angles and complex positions as the soldiers rise to put on their armor and fight the oncoming enemy. And in both Signorelli’s and Michelangelo’s works, the artists were also interested in rendering various states of emotion. In both we see several figures with mouths open in exclamation along with general expressions of anxiety and fear.

Expressions of anguish and fear (detail), Luca Signorelli, The Damned Cast into Hell, 1499-1504, fresco, 23′ wide (San Brizio chapel, Orvieto Cathedral, Orvieto, Italy) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In the end, when looking at Signorelli’s fresco, it is hard not to be amazed by the sheer volume and mass he was able to achieve in representing the figures three-dimensionally. The acidic coloration of the demons adds to the sense of complete chaos and upheaval. And in the midst of all of this action, we may even see the artist himself. If you look closely at the center of the composition, there is blue demon with a white horn who grabs a woman around her waist, and we see her struggle against her captor. That this is the artist’s self-portrait has generally been accepted. What remains unknown is the identity of the woman he grabs although she appears twice more in the fresco…can you find her?