Andrea del Verrocchio (with Leonardo), Baptism of Christ, 1470–75, oil and tempera on panel, 70 3/4 x 59 3/4″ / 180 x 152 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence)

In the contemporary art world, artists and their workshops enjoy a remarkably symbiotic relationship. Examples abound: artist Jeff Koons, for instance, floods his studio with artists who can fabricate his ideas; before him, Andy Warhol developed his thriving New York studio known as “The Factory,” where an extended entourage of artists and admirers contributed to the Pop artist’s myriad projects of the 1960s. Such relationships can be traced back through history, with roots of this symbiosis originating in the Italian renaissance, where the conceptualization of the artist’s workshop took on new meaning.

It can be difficult, however, from our contemporary perspective to reconcile the group mentality of workshop practice with the pervasive characterization of individual artistic talent. This enduring belief in the singular “genius” of artists who rose to prominence in this era is a construct slowly being dismantled through scholarly probing of the origins and functions of the renaissance workshop.

The rising profession of the artist

The emphasis on singular artistic genius was perhaps an unintended outcome of the impetus in the early years of the Renaissance to declare a new space for the profession of “artist.” Until roughly the fourteenth century, artists were typically grouped among the “mechanical arts.” This broad field included professions ranging from agriculture to architecture and was distinguished from the more lofty field of the “liberal arts.” While the liberal arts were valued higher because they stressed one’s intellectual abilities, the mechanical arts garnered less esteem because they were generally considered manual labor.

Nanni di Banco, relief showing stone and woodcarvers, c. 1416, marble, commissioned by the Guild of Stone and Woodcutters (Arte dei Maestri di Pietra and Legname), below the sculpture group of the Quattri Santi Coronati, Orsanmichele, Florence (photo: Allan T. Kohl and MCAD, CC BY 2.0)

Pressures to elevate the artistic profession, however, began in earnest in the midst of the rising Renaissance era. Organizations, for example, specifically oriented toward artistic networking and training began to appear. Prior to this moment, those practices relegated to the mechanical arts were often guided by various guilds. For example, artists would have been grouped into the Arte de Medici e Speziali (a guild for doctors and apothecaries). Around the mid-fourteenth century, though, the Compagnia di San Luca took shape in Florence. Though the structure of this confraternity was not that distinct from earlier guilds—both organizational types could be defined as groups of individuals united by a role, be it devotional or professional—the Compagnia was nevertheless notable as it was one of the first confraternities designed solely for artistic members.

The Compagnia di San Luca became a space for individual artists to gain acclaim for their talents in the first steps toward raising the artist above the rank of a menial trade. As the years progressed, this confraternal foundation became the root of even more formal academic training. Academies proliferated in the centuries to follow across the Italian peninsula and ranged from the prestigious—like Florence’s Accademia delle Arti del Disegno, whose membership included figures like Michelangelo, or Rome’s Accademia di San Luca, which launched in 1577 under the guidance of Federico Zucchari—to the more esoteric, like the later sixteenth-century Bolognese Accademia degli Incamminati, founded by the Carracci in 1582. These academies became a benchmark of accomplishment for artists, and they also underscored the idea of singular artistic talent.

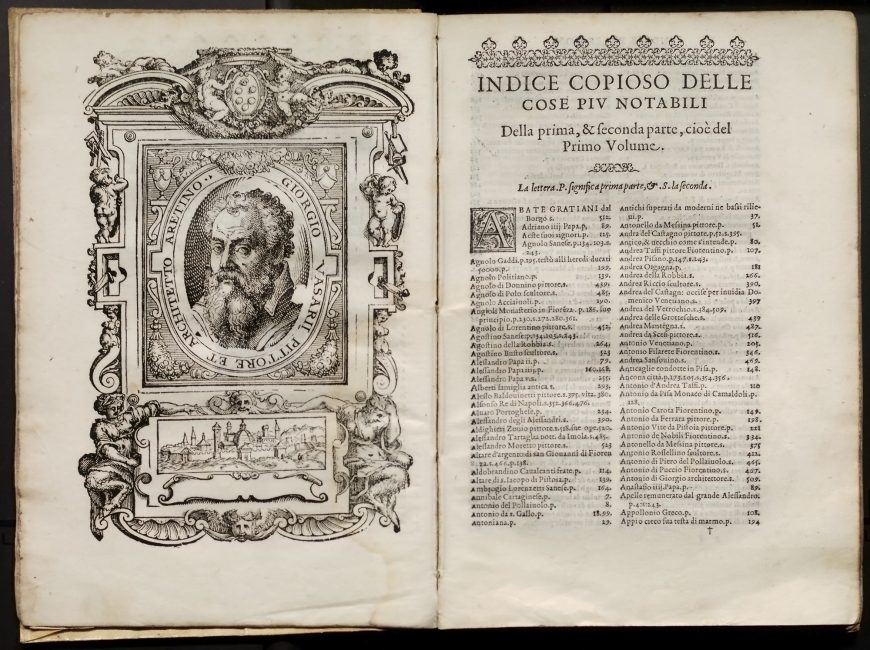

Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574), Le vite de’ piu eccellenti pittori scultori e architettori (Florence, 1568) (National Gallery of Art)

The importance of the artist’s hand

Fostered within this environment (and further emphasizing this celebration of the singular artist) was the notion of the artist’s hand— the element of a work that stressed the unique manner (maniera) or the invention (invenzione) of that artist. This was a concept highlighted across period literature, from the biographies of Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Artists (1550 and 1568) to the ideas presented in Baldassare Castiglione’s Book of the Courtier (1528). It also pervaded the arts themselves, with figures like Michelangelo placing great stock in defining his hand as a signifier of his unique talents.

Amplifying this evolution of the artist’s status was the growing presence of powerful private patrons who yearned for works by these illustrious hands. Singular families, like the Medici of Florence or the Sforza of Milan rapidly became power-players in the Renaissance art world, and while attaining such wealthy patronage was a boon from the artist’s perspective—as it meant a potential steady source of future work—it also underscored the necessity for the individual artist’s presence in a commission. In other words, implied within most acts of patronage was that the artist him- or herself would play a crucial role in the creation of the work requested. This level of involvement would, in reality, vary greatly, but for many patrons the pressures to own a work authored by these singular masters was incredibly high.

Raphael, Santa Cecilia, 1514, oil transferred from panel to canvas, 220 x 136 cm, originally in the Church of San Giovanni in Monte (Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna)

Michelangelo, Tomb of Pope Julius II, completed 1545, marble, in San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome (photo: Darren and Brad, CC BY-NC 2.0)

This meant that singular artists were ascending to professional heights—and commission rates—never seen before. Annual wages for Leonardo da Vinci, for example, by the time he arrived in Florence in 1503 were rumored to have reached 2,000 ducats annually, a salary more than double the estimated average Florentine household annual finances at the time. Raphael was awarded nearly 1,000 ducats in 1514 for a singular altarpiece, Santa Cecilia, for the Bolognese church of San Giovanni in Monte. Even more astronomical were the wages garnered by Michelangelo: in a 1524 letter, he notes the price of 10,000 ducats agreed upon by Pope Julius II years before for his planned tomb. These astronomical commissions catapulted these artists into artistic stardom, where they remained for generations as singular figures of genius.

From family to full-scale operation

Concurrent with this rising acclaim of “solitary” figures, though, was the development of the artist’s workshop. In the thirteenth century, these botteghi (singular, bottega) were originally comprised of familial networks of artists that often worked together—for example, painters Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti, who were brothers, or the father-and-son sculptor team of Nicola and Giovanni Pisano. By the century following, though, artists began to develop a coterie of assistants for their myriad commissions that extended beyond their family members. Fourteenth-century documentation, for instance, noted the various workers and students that circulated in acclaimed Sienese painter Simone Martini’s orbit; Ambrogio Lorenzetti also welcomed aides in some of his final works.

Andrea del Verrocchio (with Leonardo), Baptism of Christ (detail), 1470–75, oil and tempera on panel, 70 3/4 x 59 3/4″ / 180 x 152 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence)

To be sure, assistants and apprentices at some level were to be expected in almost any artist’s studio, thanks in part to the fact that such tutelage was the primary means for artistic training in the period. What changes in this period, though, was the sheer scale of operations: it seems clear that leading artists embraced the practice of the thriving workshop teeming with talent. Andrea del Verrocchio cultivated a workshop that welcomed rising talents like Leonardo da Vinci and Pietro Perugino (who would go on to develop his own workshop in which Raphael would garner his early training and commissions). Similarly, Domenico Ghirlandaio developed a fifteenth-century bottega that hosted, in addition to his sons, multiple apprentices to assist in his artistic output. One of these apprentices was Michelangelo who, though never establishing a workshop during his career, was known to collaborate at times, including with Venetian painter Sebastiano del Piombo while the two were working in Rome.

The benefits of the growing bottega: copies and collaborations

Such relationships presented benefits for both master and apprentice. Younger artists who were welcomed into a workshop could learn from their leader, honing their skills while garnering the formative technical exposure offered through copying drawings and collaborating on compositions.

Left: Raphael, Marriage of the Virgin, 1504, oil on roundheaded panel, 174 x 121 cm (Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan); right: Perugino, Marriage of the Virgin, 1502, oil on panel, 234 x 185 cm (Musée de Beaux-Arts de Caen)

At the same time, the master artist could also benefit greatly from maintaining a workshop, as it afforded accelerated output of commissions. Such was the relationship, we can imagine, between Leonardo and his mentor, Andrea del Verrocchio, whose works Leonardo both studied and contributed to up until the point he officially entered professional practice in 1476. The same can be said of Raphael, who carefully studied the work of his master Perugino to conjure works of near replication to meet patron’s demands. A prime example is that of his Marriage of the Virgin, which has been widely recognized for its strong parallels to Perugino’s composition of the same subject.

Marcantonio Raimondi, The Massacre of the Innocents, 1512–13, designed by Raphael, engraving, 28.3 x 43.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

This element of output was perhaps what fueled Raphael himself to build a thriving workshop in the early years of the sixteenth century in Rome, as demand for his art rapidly exceeded the rate at which he could supply it. Soon after he arrived in Rome, Raphael established a vibrant network of artists who were able to channel his “brand” and thereby meet (or at the very least, attempt to meet) the extraordinary demand for his work. Raphael’s workshop included artists working in varied media. From Giovanni da Udine, who became Raphael’s resident expert in stucco decorations and all’antica motifs, to Marcantonio Raimondi, who worked closely with Raphael in the translation of some of his images into prints, Raphael’s varied circle in essence afforded Raphael the ability to meet his patron’s every demand while still presenting finished work by his “hand.”

Probing the bounds of the bottega

The challenge in navigating this realm of the Italian renaissance workshop is that its very presence creates a paradox: how can one reconcile the notion that the individual genius we note in the work of key renaissance figures is actually thanks to the efforts of many? Modern scholars are aiming to explore this conundrum that is made all the more challenging given the fact that the legacy of these individual workshop members is, in many cases, largely obscured.

Contemporary scholarship, though, has helped to shift this conversation to recognize the “back-up bands,” as it were, that made these artistic leads so successful. By recognizing the potential that individual innovation and workshop production were not mutually exclusive concepts, scholars have made major inroads into our understanding of the popularity of and practices within Italian renaissance workshops.

Additional resources:

Bambach, Carmen, Drawing and painting in the Italian Renaissance workshop: theory and practice, 1300–1600 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999)

Dunkerton, Jill. “Leonardo in Verrocchio’s workshop: re-examining the technical evidence”. National Gallery Technical Bulletin 32 (2011): 4–31

Hirschauer, Gretchen A., and Walmsley, Elizabeth. “Verrocchio’s spring: collaboration in the painting workshop”. In A. Butterfield, ed. Verrocchio, Sculptor and Painter of Renaissance Florence (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2019): 69–85

Hirst, Michael, Michelangelo (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011)

Kwakkelstein, Michael W. “Perugino in Verrocchio’s workshop: the transmission of an antique striding stance”. Paragone. Arte. Arte. 55 (2004): 47–61

Ladis, Andrew, Wood, Caroline H., and Eiland, William U. eds., The Craft of Art: Originality and Industry in the Italian Renaissance and Baroque Workshop (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1995)

Saunders, David, Spring, Marika, and Meet, Andrew. The Renaissance Workshop (London: Archetype Publications, 2013)

Shearman, John K. G. “The organization of Raphael’s workshop”. Museum Studies / the Art Institute of Chicago (1983): 41–57

Talvacchia, Bette. “Raphael’s workshop and the development of a managerial style”. In M.B. Hall, ed., Cambridge Companion to Raphael (NY: Cambridge University Press, 2008): 167–185