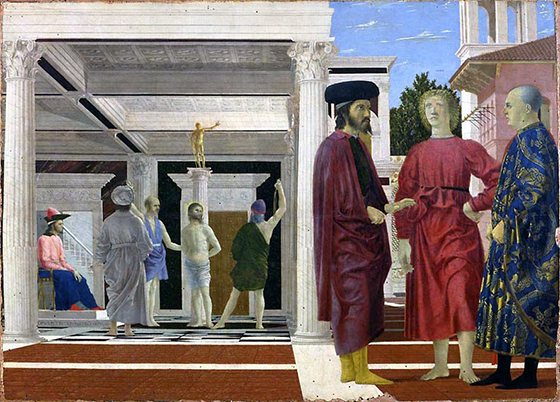

Piero della Francesca, Flagellation of Christ, c. 1455-65, oil and tempera on wood, 58.4 × 81.5 cm (Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, Urbino, Italy)

The subject of the Flagellation

Piero della Francesca’s Flagellation of Christ is proof that, sometimes, good things really do come in small packages. Despite the panel’s size (only 58.4 cm × 81.5 cm), the painting has been a mainstay in the last century in discussions of Quattrocento (fifteenth century) painting. An early example of the use of oil paint—though Piero used both tempera and oil in its execution—the work depicts the moment in Christ’s Passion when he was whipped before Pontius Pilate. Though the New Testament says very little about this moment, mentioning only that Pilate ordered Christ to be flogged, later Christian writers wrote much about the event and even speculated about the number of lashes Christ received. Though the New Testament does not say that Christ was tied to a column while being whipped, during the fifteenth century this became a convention in depictions of the scene, which Piero here follows.

A masterpiece of the early Renaissance

This painting is a masterpiece of the Early Renaissance. The figures are expressive; especially noteworthy is the face of the bearded man in the foreground. They are also given real volume through the use of modeling (the passage from light to dark over the surface of an object). True to Humanism, the painting shows a preoccupation with the classical world, as seen especially in the architecture and inclusion of the golden statue in the background. Above all, Piero’s obsession with perspective (the naturalistic recession in to space), is evident. In fact, the artist was the author of a treatise on perspective, entitled De Prospectiva Pingendi (On the Perspective of Painting) and was also known as a mathematician and geometer.

Three men in foreground (detail), Piero della Francesca, Flagellation of Christ, c. 1455-65, oil and tempera on wood, 58.4 × 81.5 cm (Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, Urbino)

Who are the men in the foreground?

But Piero della Francesca’s picture is also highly unusual. The flagellation, which is the gruesome main event, takes place in the background, while three extraneous men are painted prominently in the foreground. Piero uses two main devices to further emphasize the division of subjects. The first is setting. While the flagellation takes place inside of a covered courtyard with dramatic black and white checked tiles, the men are outdoors standing on the reddish tiles that pervade the scene. The second is the use of the orthogonal lines of the perspective, which divide the painting in half, and also delineate the interior and exterior space.

Not only is the painting strange because Piero marginalized the primary subject, relegating it to the back of the painting, but also because art historians cannot agree on who the three men in the foreground are. Theories abound.

The traditional identification of these three men is that the young man in the center is Oddantanio da Montefeltro, ruler of Urbino, flanked on either side by his advisors. All three of these men were killed in a conspiracy. In this case, it is suggested that the patron of the painting was Federigo da Montefeltro (who was later immortalized in a famous diptych by Piero) to commemorate his brother’s death and compare his innocence to that of Christ.

Art historian Marilyn Lavin offered another notable interpretation of the painting. She suggested that the two older men are Ludovico Gonzaga and a friend, who had both recently lost their sons, symbolized by the young man in the center. The painting in this case would compare the pain that the two fathers felt to that of Christ during his Passion.

Other art historians have suggested that the painting is an allegory for the suffering of Constantinople after its fall to the Muslims in 1453. In this view, the two men watching the flagellation are Murad II (the Islamic sultan who waged a decades-long war against Christianity), and Byzantine Emperor John VIII Palaiologos (against whom that war was waged). The emperor had gone to the 1438 Council of Florence to ask for protection from the Muslims, but received no aid. The three enigmatic men, then, represent nobles who stood by and let the Christian nation be destroyed.

Christ tied to a column, being flogged by two men (detail), Piero della Francesca, Flagellation of Christ, c. 1455-65, oil and tempera on wood, 58.4 × 81.5 cm (Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, Urbino)

Still another interpretation suggests that the key to understanding the painting lay in the lost inscription on the frame, which putatively said, “Convenerunt in unum,” or “They come into one.” This is a line from the Bible that was traditionally read each year on Good Friday, the day that commemorates Christ’s Passion. “They” would refer then to the Sanhedrinists, or councilmen of Israel, who were present during Christ’s suffering. In this way of looking at the panel, Piero did not include a contemporary political message, but rather painted a narrative that is true to the text, and depicts exactly what it purports to, the flagellation of Christ.

No definitive interpretation

The enigmatic nature of Piero della Francesca’s Flagellation underscores the fact that works of art, regardless of their age, continue to engender interesting art historical research. In the case of this painting, it is unlikely that a definitive interpretation will ever be accepted, as there is little documentation to support a single argument. Perhaps this ambiguity is partially why the painting continues to intrigue, and, almost 600 years later, grants multiple entry points to the viewer, drawing him into Piero’s fictional world.