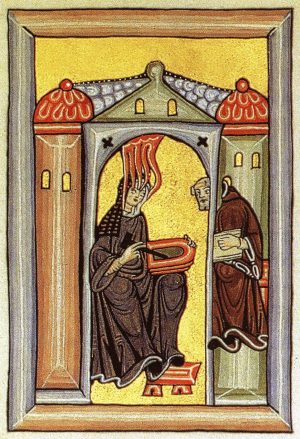

Christine de Pizan in her study, for The Queen’s Manuscript, c. 1410–1414, f. 4r (Harley MS 4431, British Library)

One of the thirty-nine women who gets a seat at the table in Judy Chicago’s iconic feminist artwork The Dinner Party, from 1979, is Christine de Pizan. As the first professional author and an important female role model from the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, she is certainly worth celebrating. A number of portraits that accompany her written works survive that show her in the act of writing. Since she often played a role in directing artists (sometimes other women) in how to depict her, we can conclude that these portraits reveal a great deal about Christine and how she wanted to be represented and understood within her lifetime.

Christine de Pizan in her study, for The Queen’s Manuscript, c. 1410–1414, f. 4r (Harley MS 4431, British Library)

Christine in Her Study

In one of the most recognizable portraits of Christine de Pizan, she wears a simple but brilliant blue dress, called a cotehardie, with her hair tucked back and covered with a double horned headdress covered by a transparent white veil. This distinctive headdress looks like one called the Attor de Gibet, or horned hennin (or possibly even the butterfly hennin), which originated in Burgundy and France.

Aristocratic or royal women typically wear them. The horns would be made to stand with wire to hold up cloth, and then often the veil draped over them. Christine communicates her noble status with her headdress, and dress. The saturated, luminous blue of the dress is painted with ultramarine, which comes from the semi-precious stone lapis lazuli which is mined in Afghanistan and was extraordinarily costly at this time. Throughout The Queen’s Manuscript, she wears the same blue cotehardie, with the expensive material undoubtedly conveying her status and a sense of luxury.

In the portrait, Christine sits within a study, framed by a rounded arch, which belongs to a larger architectural setting. She holds a pen as she writes in a book. Accompanying her in the study is a small white dog, loyally seated next to her chair. While we might wonder if Christine’s portrait is a fiction, Pizan actually did have a study with a desk, writing tools, and various books. The portrait imagines what it would have looked like. It is within her study that Pizan wrote her poems and prose texts, as well as studied the literary works of other authors–both her contemporaries and those who preceded her.

Christine gave The Queen’s Manuscript to Isabeau de Bavière, Queen of France and wife of Charles VI. The portrait of Christine writing appears early on in the manuscript, accompanying the One Hundred Ballades of a Lover and His Lady (Cent Ballades d’amant et de dame, virelyas, rondeaux), which Christine wrote around 1402.

Hildegard of Bingen experiencing a mystical vision and recounting it to the monk Volmar, from the Liber Scivias, completed 1151 or 1152 (photo: Manfred Brückels)

Christine’s portrait is remarkable for a number of reasons, including that it shows a known late medieval/early renaissance woman writing in a study. She was not, however, the first woman to be depicted in the art of writing or engaged in intellectual activities. Several centuries earlier, we find images of Hildegard of Bingen recording some of her mystical experiences (as in the Liber Scivias).

We know of other medieval women, such as Diemund of the Cloister of Wessobrun in Bavaria or the painter Ende, who wrote or illuminated manuscripts. Still, it was uncommon to show women in the act of writing since this was not understood to be their domain. Christine’s portrait is also noteworthy because it is not the sole portrait portraying her engaged in intellectual pursuits. There are a number of others within The Queen’s Manuscript, as well as in many other manuscripts as well.

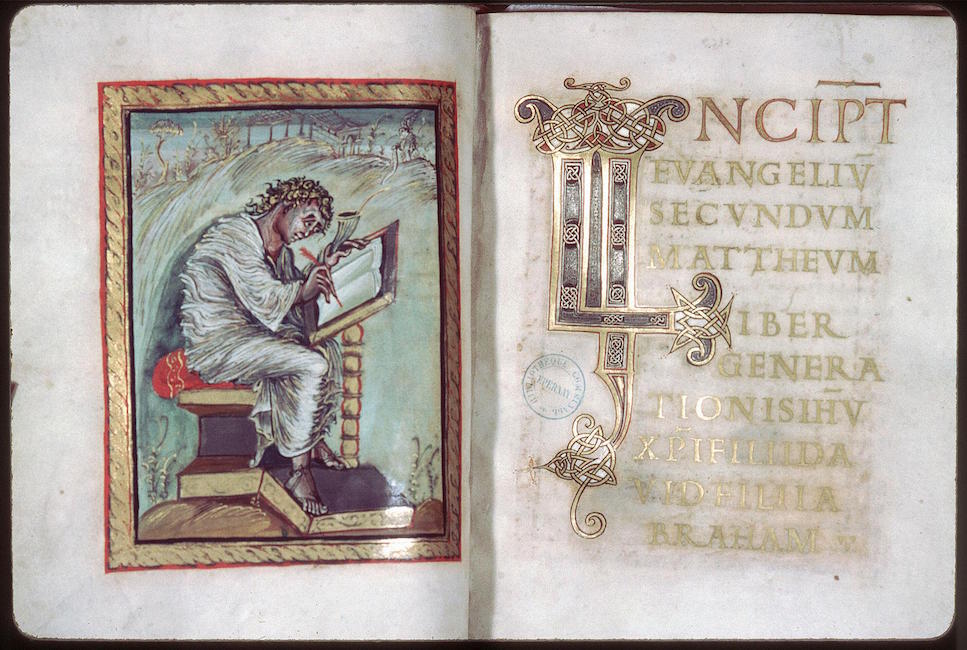

Saint Matthew, folio 18 verso of the Ebbo Gospels (Gospel Book of the Archbishop of Reims) from Hautvillers, France, c. 816-35, ink and tempera on vellum, 10 1/4 x 8 1/4 (Bibliothèque Municipale, Épernay)

Christine as author and intellectual

The portrait of Christine seated at a desk in her study while writing is a familiar type that dates back to antiquity. There are numerous examples of the solitary thinker and scholar, writing and engaged in deep thinking and other intellectual pursuits. Christine’s portraits likely called to mind portraits of the four evangelists who are often shown seated and in the act of writing, such as portrait of St. Luke from the Lindisfarne Gospels from c. 700 or St. Matthew in the Ebbo Gospels from the ninth century. Medieval scribes, such as Eadwine, were frequently displayed similarly, seated and writing in their studies or scriptoria. Christine’s portrait draws on this long heritage of images of educated authors.

Christine’s life

Christine was born in Venice, Italy, but at a young age her father (Tommaso di Benvenuto da Pizzano, or Thomas de Pizan) joined the French court in Paris as an astrologer and secretary to the king, Charles V. She had a humanist education, learning history, classical languages, and literature (among other subjects). She was married at fifteen to the royal secretary and notary, Etienne du Castel, with whom she had three children. Historical records, and even Christine herself, indicate that they got along well, which was certainly not always the case in arranged marriages.

Etienne supported Christine’s continuing education and literary endeavors. He died suddenly in 1390, when Christine was only 25, and her father died shortly thereafter, leaving Christine to support her children and mother. She turned to writing full time to make a living, and she was the first person in France to earn a living as a professional author. Later in her life, she entered a convent where she remained until her death in 1431. One of her final works was a poem celebrating Joan of Arc, likely written shortly before Joan was burned at the stake for her supposed heresy during the Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453). The War pitted England and France against one another, and Christine had witnessed the chaos and devastation the ongoing conflict wrought on the people of France.

Christine de Pizan talking with her son (detail), for The Queen’s Manuscript, c. 1410–1414, f. 261v (Harley MS 4431, British Library)

Throughout her literary career, Christine wrote on a number of topics, ranging from religion and political theory to courtly love poetry and military tactics. She also wrote in different genres, including poetry and prose texts. Many of her writings refer or allude to the upheavals that she experienced in her lifetime, including lingering deaths from the plague, an unstable crown, civil wars, and foreign occupation.

She produced many manuscripts in her own scriptorium, of which about 50 survive. There are many others (about 150) that include some of her work. Of those that she completed, we know that she determined how they would be arranged, what would be included or excluded, including the types of images. She had a direct hand in their entire composition, which is all the more remarkable as a female professional author at a time when women were not expected or encouraged to work—particularly not noble ladies—and most were not well educated.

Christine’s manuscripts, and the images she determined would be included within them, help us to learn what types of messages and ideas she hoped to convey to her readers. While she herself did not draw and paint the illustrations, it seems that she did employ female artists to produce them. She even mentions this fact in her Book of the City of Ladies (c. 1405), naming the artist Anastaise whom she said was “so good at painting decorative borders and background landscapes for miniatures that there is no craftsman who can match her in the whole of Paris, even though that’s where the finest in the world can be found…. [S]he is so well regarded that she is entrusted with finishing off even the most expensive and priceless of books.” [1]

Christine de Pizan presents her manuscript to the Queen of France (detail), for The Queen’s Manuscript, c. 1410–1414, f. 3r (Harley MS 4431, British Library)

Christine presents her manuscript to the Queen of France

Christine’s other portraits within The Queen’s Manuscript are easily identifiable because the artist (under the direction of Christine herself) consistently portrays her wearing the brilliant blue dress and horned white headdress. In the first image of the manuscript we see her kneeling and presenting a book before the Queen, who sits on a lounger within her royal chamber with a small white dog. Other ladies in waiting sit in the room. Another white dog rests at the foot of the bed, set to the right in the room. Blue textiles decorated with the royal golden fleur-de-lis adorn the walls.

The Queen and many of her ladies in waiting wear more elaborate clothes than Christine and have more intricate headdresses. The book that Christine offers is supposed to represent the very manuscript from which the image comes. This portrait was based on a type called presentation images, which typically showed a male author presenting a book to a king. Christine, and the artist she employed, modeled the image on established artistic conventions so that she could establish her position as legitimate author.

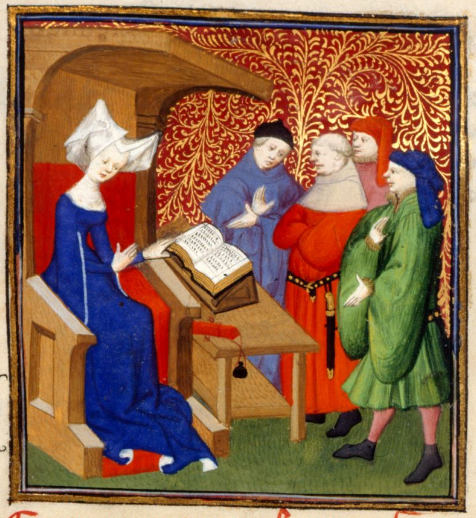

Christine instructs four men (detail), for The Queen’s Manuscript, c. 1410–1414, f. 259v (Harley MS 4431, British Library)

Christine in the act of disputation

In another portrait Christine appears at the beginning her Moral Proverbs (Proverbes moraux). She sits on what looks like a throne, once again dressed in a brilliant blue dress with a white headdress. The chair is similar to a cathedra, or a bishop’s chair, which was associated more generally with ecclesiastics but was also commonly associated with authors or men of intellectual regard in the medieval era. She has a book, open on a stand, that rests on a desk.

To the side of the desk are four men, three of whom look in her direction. The five of them seem to be engaged in conversation. Some have suggested that Christine and these four men are engaged in a debate, known as a disputation (disputa) in the Middle Ages. Disputations were common at universities, where students and professors would engage in intellectual debates to prove their wisdom. Women were not permitted at universities, so Christine’s seat in a position of authority and engaged in debate with four men communicates her intellectual abilities and elevates her to a position of authority.

This portrait, along with all of Christine’s portraits in The Queen’s Manuscript, highlight her important status. Still today, works like Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party recognize Christine’s significant contribution.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Lydia Parker.