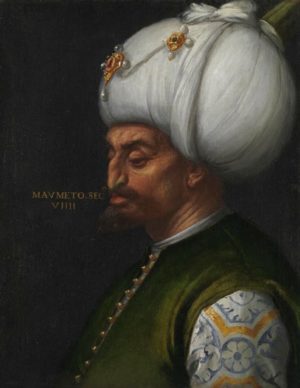

Gentile Bellini, Portrait of Sultan Mehmed II, 1480, oil on canvas, 69.9 x 52.1 cm, The National Gallery London. Layard Bequest, 1916. Currently on loan to the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

The afterlife of a painting

In a portrait attributed to the Italian artist Gentile Bellini, we see Sultan Mehmed II surrounded by a classicizing arcade, with a luxurious embroidered tapestry draped over the ledge in front of him. Gentile, already an accomplished portraitist from Venice, painted the sultan’s likeness when he spent 15 months in Constantinople at the court of the Ottoman sultan Mehmed II around 1480 on behalf of the Venetian Republic.

Today this famous portrait belongs to the National Gallery of Art, London. It has had many “afterlives,” that is, many ways it has been re-interpreted and understood since it was produced nearly 550 years ago.

Circle of Gentile Bellini (?), Portrait of Sultan Mehmet II with a Young Man, c. 1500?, oil on panel, 33.4 x 45.4 cm (purchased at Christie’s London by the Municipality of Istanbul in June 2020)

For example, in June of 2020, the Municipality of Istanbul spent over a million dollars at auction for a double portrait featuring the face of Sultan Mehmed II and a young man. The painting is mysterious: it is uncertain who painted it, when, or where, and the identity of the second figure is unknown. The image of the sultan, however, is based on Bellini’s well-known London picture, and the reputation of the mystery painting—as well as Istanbul’s risky purchase—depends on its fame. This is just the most recent, and ongoing, of the London portrait’s “afterlives,” which are the subject of this essay. Before exploring them, however, we must begin with the original painting and its production.

A Venetian travels to paint Sultan Mehmed II

When the London portrait was created, Mehmed was sultan of the Ottoman empire, and ruled from Constantinople (now Istanbul), the city that had been the capital of the Byzantine empire until Mehmed conquered it in 1453. (The Ottomans were Muslim, the Byzantines were Orthodox Christians, and European rulers were faithful to the Church in Rome, or to what we now call Catholicism—and these divergent creeds were no small matter.) Even today, Mehmed is known in Turkish as “Fatih,” or “conqueror.” In addition to being a warrior and politician, he was a great patron, bringing artists and architects together to write, paint, and build. When he petitioned the Venetians to send him artists skilled in portraiture, they sent Gentile Bellini, who seems to have had rare access to the private spaces of Mehmed’s palace. The London portrait is believed to have been produced there, and was probably transported to Italy soon after Mehmed’s death in 1481—by whom is unclear.

The painting resembles many other European portraits of the day, and is dramatically different from contemporary Ottoman portraiture. A single figure, bust-length and life-sized, poses in elaborate dress that reveals his rank and wealth. He is not quite in profile but turned ever so slightly forward, a visual strategy that, along with the carved stone arcade, gives a sense of depth and creates the illusion that the sultan actually sits before us. That illusion is disrupted by the flat, black background and six crowns that seem to float behind him, symbols either of his territorial rule or his place in the chronology of Ottoman sultans. Gentile signed the architectural plinth with his name and date, as a kind of painterly proof of his status as an eyewitness to the sultan (who was often hidden from view) and of the truthfulness of this image.

Why would Mehmed commission such a picture? The answer likely lies in his general curiosity as a patron. We know he studied classical languages, was fascinated by maps, and followed the latest advancements in military architecture. He collected coins and medals, and was aware of their power to glorify a ruler through the circulation of his image. In addition, Mehmed’s interest in portraiture suggests he was up-to-date on some of the most revolutionary things that were happening in Italian painting—in particular, new attempts to depict the world as if it were seen through a window, to paraphrase the contemporary art theorist Leon Battista Alberti. Commissioning a skilled Venetian artist to paint a life-sized, illusionistic portrait might have been a test of just what, exactly, this new form of image making could do.

Gentile Bellini, Mehmet II, c.1480 (later casting), bronze, 9.38 cm (Samuel H. Kress Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.)

Master of the Vienna Passion (attributed), El Gran Turco (The Great Turk), c.1470, engraving (Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Two points need to be clarified before we move on. First, the London portrait is sometimes considered the first “realistic” representation of a Turk to arrive in Europe (most images of the time were demonizing stereotypes, like “The Great Turk” engraving in Berlin). Yet it is misguided to assume Mehmed was focused on advancing European knowledge of foreigners. If, as is possible, he intended to circulate his image through copies of Gentile’s portrait, his goals were fame and power, not ethnographic instruction. Second, the equally misguided notion that Islam forbids naturalistic imagery also needs correcting: such imagery had a long tradition, especially in illuminated manuscripts, and was often acceptable outside religious contexts. Moreover, for sultans, rules and norms did not apply.

Mehmed’s portrait in Italy

How and when Gentile’s portrait of Mehmed arrived in Italy is another of its mysteries. In all probability, it landed in Venice shortly after the sultan’s death in 1481, and this is what the Ottomans thought—they even sent a delegate there to recover lost portraits of the sultans one hundred years after Gentile’s trip east (they failed, returning with modern works instead, including the one by an artist in the circle of Veronese). But the painting now in London did not come to light until hundreds of years later, in 1865, when it was purchased from an impoverished nobleman by the British explorer, collector, and eventual ambassador to Constantinople, Austen Henry Layard. Layard’s own circumstances offer an excellent introduction to the reception of Gentile’s painting in the modern era.

Circle of Paolo Veronese, Portrait of Sultan Mehmed II, 1578 or later, oil on canvas, 69 x 54 cm (Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich)

Like Gentile, Layard traveled to the Ottoman court in a diplomatic position, meeting privately at the palace with the reigning sultan, Abdülhamid II. As a young man, Layard had excavated, published, and sent back to London a trove of Assyrian artifacts from Nineveh (in modern Iraq), and had authored several illustrated volumes about his experiences.

In these roles, Layard was an archetypal “Orientalist,” someone whose status, power, and actions depended on a colonial imbalance between Europe and the Near East. On occasion, Layard even played at “Oriental,” donning headscarves and swords. As a collector, he was particularly proud of his portrait of Mehmed, which he immediately recognized as the famous lost work by Gentile Bellini. But what did he see when he looked at it, hanging in his Venetian palace among assorted fragments of Assyrian architecture? Might he have seen his own experiences as ambassador reflected back at him? One journalist of the period suggested as much, but we can only speculate—recognizing at the very least how different Layard’s interactions with the picture were from that of Mehmed.

Lowering the Great Winged Bull, lithograph, frontispiece to Austen Henry Layard, Nineveh and its Remains (London, 1849)

By 1915, Gentile’s portrait had been at the center of two other conversations that again reframe its meaning. The first has to do with definitions of national patrimony, a topic that is very much in the news today. Layard had willed his collection, which hung in Venice, to the National Gallery in London. But on the death of his widow, Enid, in 1912, the Gallery found itself up against several recent Italian laws that aimed to keep the greatest “Italian paintings” in Italy. Gentile’s portrait of Mehmed was among them: it “was regarded [by the Italians] somewhat as the Athenians regarded the Elgin Marbles,” wrote the British ambassador to Italy, making reference to the Greek sculptures that are still at the center of patrimony controversies. That the portrait was painted in Constantinople for an Ottoman patron by a traveling Venetian, that it was an inherently global object, was not mentioned. But these claims offer another way of thinking about Gentile’s picture—and presented a significant obstacle to its transport to London as well. (How the painting got out of Italy and into England in 1916 lay in the legal fine print.)

The second, equally philosophical controversy involved its status as a portrait. Layard left his collection to the National Gallery, but, in a clumsy turn of phrase, his will opened the door for his nephew to claim rights to all of his portraits. Both sides took legal action, bringing in experts to decide just what, exactly, constitutes a portrait. The surviving dossier reads like art theory crossed with intellectual property law and the observations of a private eye. Debate centered on questions of intent, interpretation, and continuity (“once a portrait, always a portrait”?); on whether there is a distinction between historical portraits and family portraits; and on how Layard organized, wrote about, and displayed his collection. Gentile’s image of Mehmed was the star witness, the one painting the antagonists consistently tussled over.

Again the National Gallery won, and hung the portrait prominently in its entrance hall. Over the next century, however, its fortunes swung dramatically, along with shifting understandings of conservation and authenticity (problematic, since only an estimated 10% of the paint is original to Gentile—over time, the canvas was damaged and was on several occasions repainted), as well as evolving attitudes within museums about how and why certain paintings are valued over others. After being one of the museum’s prize acquisitions, Gentile’s picture spent decades in the lower level galleries for “problem works.” In 2009, it was moved across London to the Victoria and Albert Museum where, along with carpets, ceramics, and metalwork, it is now part of a gallery dedicated to art and trade in the early modern Mediterranean. These shifting appraisals say more about the frames of interpretation than they do about the painting itself that, aside from the abrasions of time, has not changed.

The portrait today

In 1999, Gentile’s portrait of Mehmed traveled to Istanbul to star in a one-painting show that drew huge audiences and attention. “We have seen this picture so many times, in so many schoolbooks and on so many walls over so many years that it’s really imprinted on our brains,” one Turkish viewer told an American reporter. For many, aware of Mehmed’s broad patronage and support of a Venetian painter, the image signified a tight bond to Europe. Notably, it was also in 1999 that Turkey made its first petition for membership in the European Union.

In the two decades since, however, relations between Turkey and the West have soured, and Ottoman imagery, including that of Mehmed II, has been coopted in Turkey by more conservative political forces to stand for a separatist, nationalistic identity. In this “neo-Ottoman” framework, Gentile’s picture takes on new meaning, with emphasis on the sultan as “Fatih,” conqueror—thus it is this face that welcomes visitors to Istanbul’s new Panorama 1453 Conquest Museum, which celebrates the Ottoman taking of the city from the Byzantines centuries ago. The same face also appears on magnets, notebooks, tote bags, and countless internet memes, in a thoroughly contemporary stew of humor, nationalism, and entrepreneurship.

Is this painting exceptional in the many permutations of meaning we give to it? Probably not. Gentile Bellini’s portrait of Sultan Mehmed II is more likely an object lesson in how many lives a single artwork can take on, and of the value to be found in deep looking and extended research.

Additional resources:

This essay is based on Elizabeth Rodini, Gentile Bellini’s Portrait of Sultan Mehmed II: Lives and Afterlives of an Iconic Image (I.B. Tauris/Bloomsbury, 2020). An extensive bibliography and notes can be found there (and see the publisher’s site).