Benozzo Gozzoli, frescoes on the east and south walls, Magi Chapel, 1459, Medici Palace (Palazzo Medici, also known as the Palazzo Medici Riccardi)

Inside the Medici Palace, just off the palace’s central courtyard at street-level, is the Medici Chapel (or Magi Chapel). Completed in the mid-fifteenth century, this intimate room still dazzles its visitors with its vividly painted frescoes and gold leaf which is in stark contrast to the palace’s rather modest exterior. One can easily imagine the glittering effect of flickering candlelight in the opulent space of the Medici Chapel.

The Medici family was a wealthy and powerful Florentine family, whose fortune was built on their banking industry. The Medici Bank was initiated in the late 14th century under Giovanni di Bicci de’ Medici, but the family’s economic power ultimately helped them garner increased political power, and they became the rulers of Florence (and later Tuscany) for much of the fifteenth through early eighteenth centuries.

Michelozzo, Medici Palace (Palazzo Medici, also known as the Palazzo Medici Riccardi), 1445–60, Florence, Italy (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

While the patron of the Palazzo, Cosimo de’ Medici (“il Vecchio”), wanted his family home to have an austere, geometric public face (so as not to be perceived as ostentatious), the family’s wealth and influence was strategically displayed throughout the interior, including in the Medici Chapel. This balance reflects Cosimo’s calculated efforts to maintain power and favor in Florence while avoiding conspicuous outward displays of the family’s wealth. This was especially important in the fifteenth century when power in Florence was constantly oscillating between the Medici and the Florentine Republic. So, it was beneficial for the Medici to avoid appearing too pretentious and greedy in their public displays of wealth.

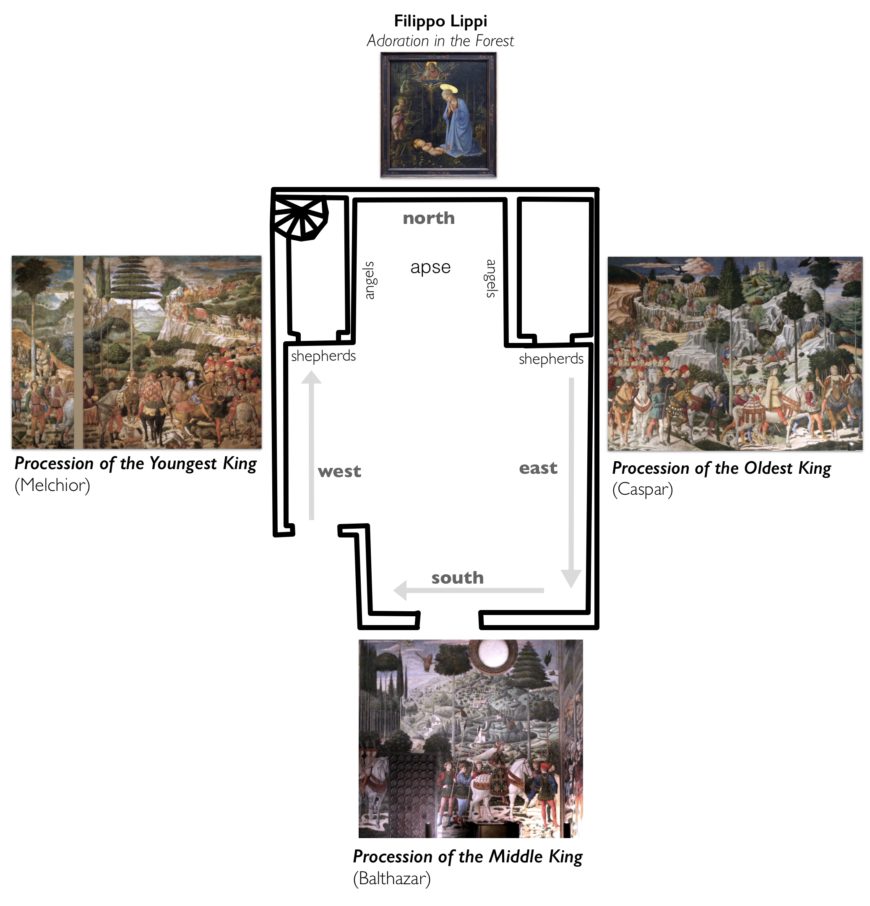

Benozzo Gozzoli, looking towards the apse and Fra Filippo Lippi’s altarpiece, Magi Chapel, Medici Palace (photo: Беноцо Гоцоли, CC 3.0)

The design of the Medici Chapel

The small Medici Chapel was meant to function as a space of private worship for the family. For the space’s fresco decoration, the Medici chose the painter Benozzo Gozzoli, who had trained under the Florentine Fra Angelico (known for his frescoes in the monastery of San Marco, a decorative program which was also funded by Cosimo il Vecchio).

Filippo Lippi, The Adoration in the Forest, 1459, oil on poplar wood, 118.5 x 129.5 cm, originally in the apse of the Magi Chapel Medici Palace, north wall (Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin)

Such private spaces for worship—whether in a public setting, such as a local church, or in one’s family home—were quite common for rulers and the wealthy in early modern Italy. However, papal permission for the construction of a private family chapel inside a residence was required, and the Medici had obtained this through Pope Martin V by 1442.

The completion of the chapel’s decoration was mostly overseen by Cosimo’s son, Piero di Cosimo de’ Medici (“the Gouty”), who took over as the head of the family after his father’s death in 1464. Piero also commissioned a portable family altarpiece from the Carmelite painter Fra Filippo Lippi for the chapel, which depicts the Adoration in the Forest, or Mystical Nativity. In the altarpiece, the Virgin Mary kneels beside the Christ child, who lays on a blanket of grass and flowers in a dark forest, while God the Father and the dove of the Holy Spirit appear above them, and Saint John the Baptist stands to their side.

Benozzo Gozzoli, Procession of the Youngest King, Caspar, east wall, Magi Chapel, 1459, Medici Palace (photo: Sailko, CC BY 3.0)

The Magi

A feast for the eyes, Benozzo Gozzoli’s frescoes cover every wall of the small chapel, enveloping the viewer from all sides. Said to have been painted in about 150 days in 1459, the theme centers around three biblical kings from far-reaching lands, commonly known as the Magi or wisemen. According to Christian tradition, these men visited the Christ child shortly after his birth and brought expensive and exotic gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. The three kings and their large entourage are painted with rich detail as they complete their long journeys.

Their procession extends across the east, south, and west walls of the nearly perfectly square space, leading towards the north wall which incorporates an unusual square apse (they are most often hemispherical). With Lippi’s altarpiece at its center (today a copy of the original work), the decoration of the apse denotes a separate realm, where frescoed angels appear to worship on either side of the Adoration in the Forest altarpiece.

Benozzo Gozzoli, detail of a figure with gold leaf applied to the sleeves of his blue shirt, south wall, Magi Chapel, 1459, Medici Palace (photo: Sailko, CC BY 3.0)

The altarpiece and the frescoes were conceived of as a united program, functioning together to produce an overall effect more powerful and spiritually moving than its constituent parts. Throughout the chapel, Gozzoli alternated between buon fresco and fresco secco, and in the final stages of the project, areas of gold leaf were applied. The gold leaf adds an opulence to the imagery and its use recalls what is now referred to as the International Gothic style, long associated with princely patronage.

The gold-leaf applied throughout the composition helped to create a shimmering, ethereal experience when viewed in candlelight. The incorporation of this expensive material, as well as the use of costly pigments like ultramarine blue, made from lapis lazuli, cast the Medici in the role of the Magi, “giving” Christ an expensive gift by way of paying for the construction and decoration of this space. This effect is reinforced by the inclusion of portraits of Medici family members in the guise of the Magi and their entourage (explored below). Spotted throughout the frescoed walls are orange trees, a common Medici symbol reflective of the palle (balls) of their coat of arms, lest any future visitors question the patronage of the space.

Benozzo Gozzoli, leopard (detail), west wall, Magi Chapel, 1459, Medici Palace (photo: Sailko, CC BY 3.0)

Across the Chapel’s walls, the Magi travel through an incredibly rich, detailed landscape, full of carefully rendered flora and fauna. Deer, hunting dogs, rabbits, various birds, monkeys, camels, and exotic cats galivant amongst the exquisitely dressed crowds. This verdant landscape also draws influence from works of the International Gothic style in its moments of careful ornamentation and patterning, bright and rich colors, and extreme attention to every tiny detail.

Benozzo Gozzoli, landscape (detail), south wall, Magi Chapel, 1459, Medici Palace (photo: Sailko, CC BY 3.0)

The perpetual procession of the Magi

Each of the three walls showing the long journey of the Magi focuses on one of the three kings: Melchior (the eldest king), Balthazar, and Caspar (the youngest). Interestingly, visitors to the chapel do not see the more commonly represented end of their journey, the moment when the three kings have actually reached the Holy Family and they adore the newborn Christ Child, such as we see in Gentile da Fabriano’s Adoration of the Magi altarpiece. The patron of Gentile da Fabriano’s work, Palla Strozzi, was part of a rival Florentine banking family. In this work, the Strozzi family also associated themselves with the generous Magi. Their Adoration, however, was visible to the general public, located in the family’s chapel in the church of Santa Trinità. Contrasting more common period depictions of the Magi having reached their destination (the newborn Christ child), in Gozzoli’s private Medici Chapel frescoes, the Magi are frozen in a perpetual and unfulfilled journey across the walls of the room. Instead, it was the flesh and blood members of the Medici family who worshipped before the altar in this space who were meant to realize the goal of reaching and adoring the Holy Family.

Benozzo Gozzoli, Adoration of the Magi, cell of Cosimo de’ Medici (San Marco, Florence, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

This kind of role-play was typical of many patrons, including the Medici, who frequently liked to imagine themselves as similar to these wealthy kings of the biblical past who adorned Christ with gifts. Another example of the Medici associating themselves with the Magi is found in Cosimo il Vecchio’s personal, private cell in the monastery of San Marco, also located in Florence. This room was used by Cosimo as a meditative escape, and he chose to have it decorated with a scene of the Magi giving gifts to the newborn Christ child. This image of the adoration of the Magi in his own private monastic retreat allowed Cosimo to reflect on important Christian stories while simultaneously considering his own family’s “similarities” to these three kings. Notably, this particular cell in San Marco was decorated by both Fra Angelico and one of his star pupils—Benozzo Gozzoli himself.

The Medici become the Magi

In the Medici Chapel, accompanying the Magi and their entourage on each of the three walls, recognizable portraits of members of the Medici family can be found riding along with each group.

Melchior, the oldest king, on the far left, and a figure in the center may be the young Giuliano de’ Medici. Benozzo Gozzoli, Procession of the Oldest King, Melchior, west wall, Magi Chapel, 1459, Medici Palace (photo: Sailko, CC BY 3.0)

A long caravan of figures leads several camels, donkeys, and horses, whose backs all appear to be loaded with goods, if not carrying people. Behind this caravan, the oldest king, Melchior, is accompanied by a group of contemporary figures, many of whom are recognizable allies of the Medici. Dressed in blue and lingering in a princely group just in front of Melchior, a figure proposed as a portrait of the young Giuliano de’ Medici rides his horse while accompanied by two exotic cats. This young man looks out towards the viewer, inviting them to contemplate this important journey. Here, Gozzoli includes his own portrait as one of the many pilgrims who travel alongside Melchior.

Benozzo Gozzoli, Procession of the Middle King, Balthazar, south wall, Magi Chapel, 1459, Medici Palace, Florence (photo: Sailko, CC BY 3.0)

The second king, Balthazar, continues the procession behind Melchior. Bearded, somewhat darker-skinned, and wearing a rich green and gold embroidered gown, Balthazar’s appearance indicates the vast global range from which the three kings came.

Benozzo Gozzoli, Procession of the Youngest King, Caspar, east wall, Magi Chapel, 1459, Medici Palace, Florence (photo: Sailko, CC BY 3.0)

It is important to note that the relative age of the three Magi is changeable in works of the period. For example, Balthazar is often identified as the youngest king, and is increasingly said to hail from the African continent. However, Gozzoli’s youngest king is Caspar. Taking on the role of Caspar is a young Lorenzo (il Magnifico) de’ Medici, soon to become one of the greatest Medici rulers of Florence’s history. He rides a white horse while leading the last part of the procession, another large group of lay people. The young Lorenzo may have been pictured as Caspar because his birthday fell on the Feast of Caspar, January 1.

Benozzo Gozzoli, Cosimo il Vecchio (left) and Piero di Cosimo de’ Medici (right), east wall, Magi Chapel, 1459, Medici Palace, Florence (photo: Sailko, CC BY 3.0)

Next in line in the group that follows Lorenzo/Caspar is Lorenzo’s father, Piero, and then his grandfather (the original patron of the Palazzo Medici), Cosimo il Vecchio. The huge group behind them includes recognizable depictions of many other important leaders of the period with close associations to the Medici, such as Sigismondo Malatesta (Lord of Rimini) and Galeazzo Maria Sforza (Duke of Milan), along with illustrious Florentines, like the humanists Marsilio Ficino and the Pulci brothers, important members of various Florentine guilds, and none other than Gozzoli himself.

Benozzo Gozzoli, self-portrait (detail), east wall, Magi Chapel, 1459, Medici Palace, Florence (photo: Sailko, CC BY 3.0)

Yes, the artist included his own portrait twice, just in case you missed him the first time. He looks directly out at the viewer in both instances. Here at the end of the procession, Gozzoli’s red hat is inscribed in gold leaf with the words, “Opus Benotii” (the work of Benozzo), the only legible text found on anyone’s attire. By incorporating these two self-portraits into the scene, Gozzoli made sure that he would be remembered long after his death, and even more importantly, that he would be remembered in connection with the powerful Medici family.

Benozzo Gozzoli, Black bowman (detail), east wall, Magi Chapel, 1459, Medici Palace, Florence (photo: Sailko, CC BY 3.0)

Diverse figures

Throughout the procession, viewers also find diverse characters, such as Black individuals and figures dressed in Ottoman fashion (see below). These figures are nods to the Medici’s broad reach of power and a desire to display their worldliness. In 1453, the Ottoman Empire overtook the Christian city of Constantinople and the Byzantine empire fell. As a result, the relationship between Christians and Muslims became more complicated in the latter half of the fifteenth century. Extensive trade still occurred through Ottoman territories, so Medici diplomats and traders were in frequent contact with Ottoman peoples during this period.

Benozzo Gozzoli, in the middle ground figures wear Ottoman inspired clothing and accessories (detail), west wall, Magi Chapel, 1459, Medici Palace, Florence (photo: Sailko, CC BY 3.0)

The depiction of figures like Melchior in distinct Eastern-inspired dress, along with several turbaned figures dotting the frescoes, reflect the visibility of Ottomans in the lives and business associations of wealthy Europeans like the Medici. Importantly, the fall of the Byzantine empire to the Ottomans meant that the Holy Land was now under Islamic rule. These non-European figures, therefore, are also simply to be read as signifying the Holy Land. This is seen in other Italian works from this period, such as Carlo Crivelli’s Madonna and Child, which incorporates turbaned figures in the background to help situate the scene in the Holy Land for Renaissance viewers. Similarly, the Black individuals that Gozzoli incorporates, such as the Black bowman walking along with Caspar’s entourage, might be read as both simple comments on the vast reach of Medici power, as well as a reflection of the prominent period belief that one of the three kings was from the African continent.

By including so many varied and recognizable faces, the Medici used this space to celebrate their political and economic power alongside a show of their piety. In fact, in an effort to convey the family as humbly as possible (despite literally comparing themselves to the wealthy kings that brought expensive and exotic gifts to the Holy Family), the family had most of their own portraits incorporated at the end of the procession, as part of the youngest king’s retinue and therefore physically farthest from the goal of reaching the newborn Christ child.

The Medici access the heavenly realm

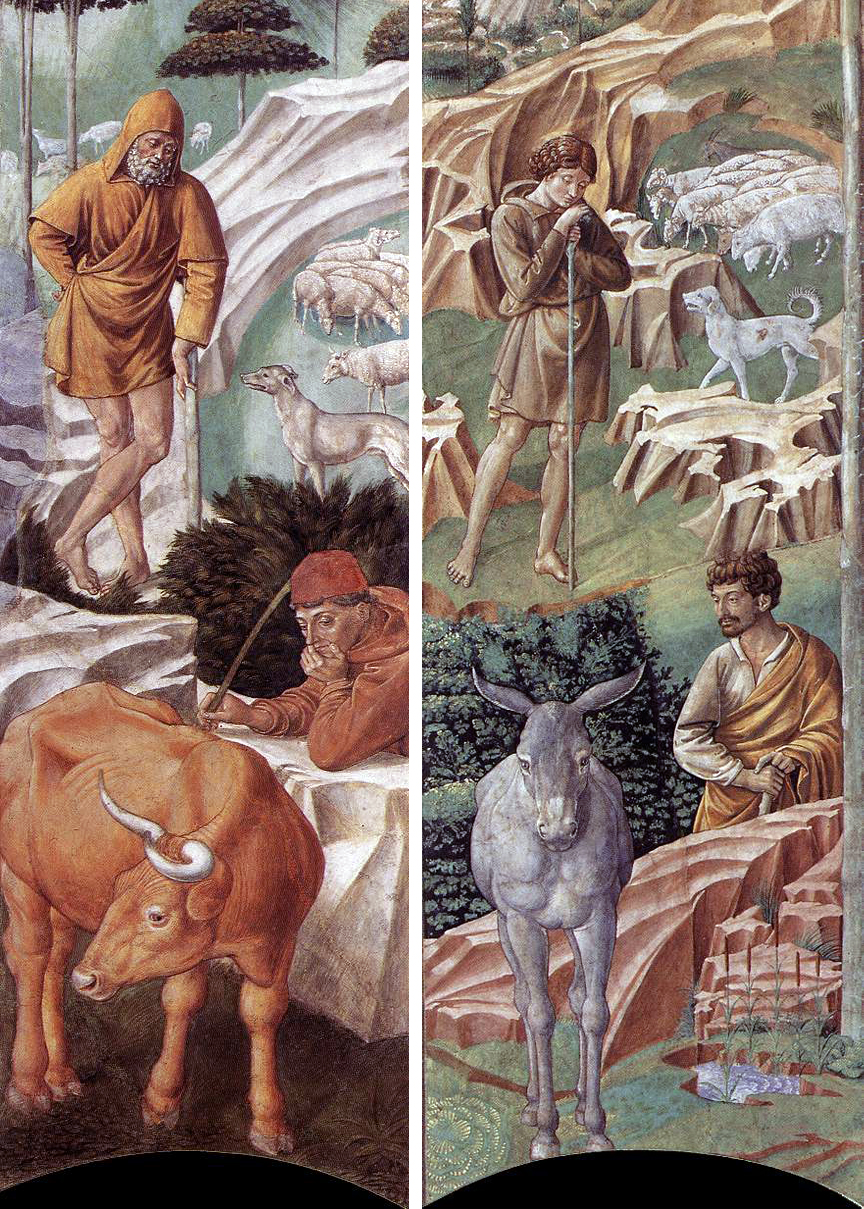

Benozzo Gozzoli, shepherds on the left and right walls of the apse, Magi Chapel, 1459, Medici Palace, Florence

While the painted members of the Medici family are mostly at the end of the long procession, when they knelt before the altar in the physical space of the chapel, they were actually afforded access to the space closest to Christ (depicted in Fra Filippo Lippi’s altarpiece). Two shepherds in the frescoed landscape depicted on either side of the apse’s entrance model the worshipful poses that would have been adopted by members of the Medici family, gazing upon the Christ child and completing the journey perpetually unrealized by the processing Magi on the surrounding walls.

Additional resources

Franco Cardini, The Chapel of the Magi in Palazzo Medici (Florence: Mandragora, 2006).

Diane Cole Ahl, Benozzo Gozzoli (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996).

Darrell Davisson, “Magian ‘Ars Medica’, Liturgical Devices, and Eastern Influences in the Medici Palace Chapel,” Studies in Iconography vol. 22 (2001): pp. 111–62.

Rab Hatfield, “Cosimo de Medici and the Chapel of His Palace,” in Cosimo “il vecchio” de Medici, 1389–1464: Essays in Commemoration of the 600th Anniversary of Cosimo de Medici’s Birth, ed. Francis Ames-Lewis (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992).

Rab Hatfield, “Some Unknown Descriptions of the Medici Palace in 1459,” The Art Bulletin 52, no. 3 (1970): pp. 232–49.

Cristina Acidini Luchinat, The Chapel of the Magi: The Frescoes of Benozzo Gozzoli in the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi, Florence (London: Thames & Hudson, 1994).

Philip Mattox, “Domestic sacral space in the Florentine Renaissance palace,” Renaissance Studies, special edition: Approaching the Italian Renaissance Interior: Sources, Methodologies, Debates 20, no. 5 (2006): pp. 658–73.

Howard Saalman and Philip Mattox, “The First Medici Palace,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 44, no. 4 (1985): pp. 329–45.

Allie Terry-Fritsch, Somaesthetic Experience and the Viewer in Medicean Florence: Renaissance Art and Political Persuasion, 1459–1580 (Amsterdam University Press, 2020).