“The walled garden,” in the Roman de la Rose, c. 1490–1500, f. 12v (Harley MS 4425, British Library)

The woman question

In the late Middle Ages, one of the most popular books was the Romance of the Rose (Roman de la Rose), begun in 1237 by Guillaume de Lorris and expanded by Jean de Meun some decades later. The lengthy medieval poem describes a dream vision about romantic love or the art of love. At the center of the poem is a young man who, while asleep, encounters a garden of love. While there, he sees a rose with which he falls in love. During his dream journey he meets various allegorical figures or personifications. Eventually the young man will acquire the rose, deflowering it. The book was a bestseller, with many manuscripts illustrating the story, but it was also controversial for its descriptions of courtly love, women, and marriage.

In the early fifteenth century, a major debate about the Romance of the Rose ensued, as did the nature and role of women. It was called the querelle de femmes, or “the woman question.” It pitted important thinkers against one another.

One of the most active participants in this debate was Christine de Pizan, the first professional author and a woman to boot, and she, along with Jean Gerson (chancellor of the University of Paris) and others, challenged the misogynistic text’s ideas as well as broader societal notions of womanhood. She disagreed with the negative, misogynistic attitudes toward women that she felt the book promoted and penned numerous letters to defend women. Her participation in the quarrel is a reason that Christine is often called one of the first feminists. In her poems and prose texts, she would also argue for the rights of women and found opportunities to celebrate women’s achievements.

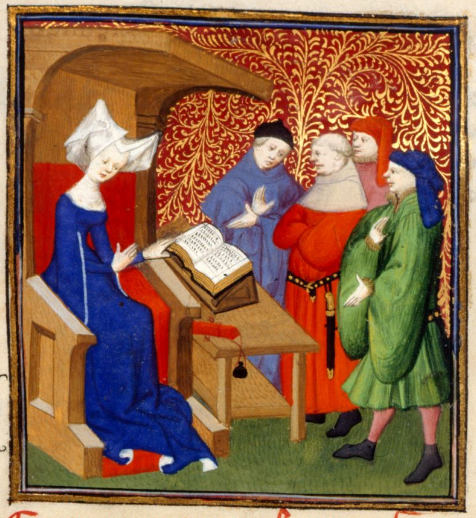

Christine de Pizan in her study (detail), for The Queen’s Manuscript, c. 1410–1414, f. 4r (Harley MS 4431, British Library)

The Book of the City of Ladies

Pizan’s most famous text, called The Book of the City of Ladies, written around 1404–05, is probably the best expression of her views on women. The text begins with Christine describing how she was sitting in her study, reading. She likely had in mind a space similar to the one we see in her portrait in the Queen’s Manuscript, in which the artist—possibly even a female manuscript painter—depicts Christine seated at a desk in her study, with writing implements and accompanied by a dog.

In The Book of the City of Ladies, she reads a book about women that she finds unpleasant and shocking. She feels sad and depleted after reading it, especially because the book complained about women, and especially marriage. At this moment of sadness, she is visited by three ladies, Rectitude, Justice, and Reason, who represent different virtues. They tell Christine to build a city of ladies, and to fill it with women worthy of recognition for their intellect, compassion, and strength.

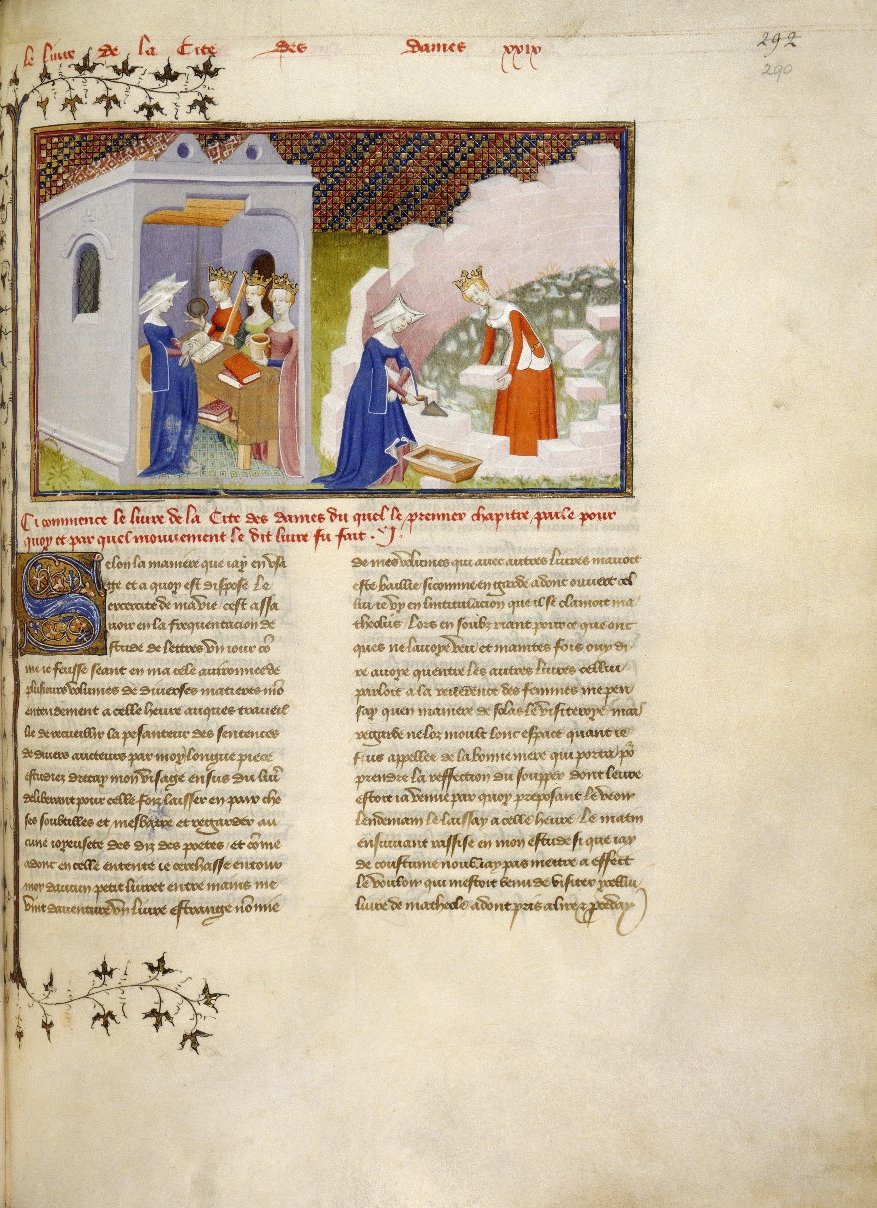

Christine de Pizan meets the three ladies and lays the foundation of the city of ladies, for The Queen’s Manuscript, c. 1410–1414, f. 290r (Harley MS 4431, British Library)

The book proceeds to catalogue important women (historical, biblical, and mythological), and includes individuals such as Judith, the Amazons, Blanche of Castile, saint Cecilia, and Sappho. Her extensive catalogue of women is indebted to Boccaccio’s On Famous Women, from 1361–62, which included short biographies of famous women (mythological and historical). Still, Christine’s text has many more women in it, and the text passionately defends them, especially their education.

The education of women

At one point in The Book of the City of Ladies, Christine discusses women’s education with Lady Rectitude, extending her arguments of the “querelle” and providing another opportunity to defend women and their right to be educated.

Christine, said, ‘My lady, I can clearly see that much good has been brought into the world by women. Even if some wicked women have done evil things, it still seems to me that this is far outweighed by all the good that other women have done and continue to do. This is particularly true of those who are wise and well educated in either the arts or sciences, whom we mentioned before. That’s why I’m all the more amazed at the opinion of some men who state that they are completely opposed to their daughters, wives or other female relatives engaging in study, for fear that their morals will be corrupted.’

Rectitude replied, ‘This should prove to you that not all men’s arguments are based on reason, and that these men in particular are wrong. There are absolutely no grounds for assuming that knowledge of moral disciplines, which actually inculcate virtue, would have a morally corrupting effect. Indeed, there’s no doubt whatsoever that such forms of knowledge correct one’s vices and improve one’s morals.”

Christine de Pizan, The Book of the City of Ladies, trans. Rosalind Brown-Grant (London: Penguin, 1999), part 2:36.

Christine instructs four men (detail), for The Queen’s Manuscript, c. 1410–1414, f. 259v (Harley MS 4431, British Library)

Christine’s defense of women’s education underscored her own education and her work as a writer. Other painted portraits of Christine, including those within the Queen’s Manuscript, portray her engaged in writing or disputation as visual arguments to support women and their education.

Building a city of ladies

Christine de Pizan meets the three ladies and lays the foundation of the city of ladies, for The Queen’s Manuscript, c. 1410–1414, f. 290r (Harley MS 4431, British Library)

In another image from The Queen’s Manuscript, the artist depicts Christine in her study as she is visited by the three allegorical ladies and as she begins to construct the city. Christine once again dons her blue dress and white horned headdress, and she rises from her chair to speak with her three visitors.

The three crowned ladies all hold attributes that relate to who they personify, as Christine describes in the text itself. Reason holds a mirror (symbolizing wisdom), Rectitude a ruler (symbolizing judgment), and Justice a golden container (symbolizing justice and salvation). Reason holds the mirror up to Christine so that she can see herself for who she is and not in the way that men have negatively addressed women. Rectitude’s ruler is to help Christine measure the materials needed to build the city and to separate good from bad, right from wrong. God gave Justice the golden container, and it is a reminder to live morally and justly in order to achieve salvation because Justice will dole out “the rightful portion” according to how each person lives.

In the right portion of the image, Christine is shown actively engaged in the building of the city, holding a trowel as she plasters stones one by one to construct the outer wall of the city. Reason assists her, carrying a brick to Christine. In a single image, Christine is an author, an intellectual, an individual graced with divine presence, and an architect at work.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Lydia Parker.

Additional resources

View the entire Queen’s Manuscript at the British Library

The Making of the Queen’s Manuscript project

Read about the Roman de la Rose on the British Library website

View a copy of the Roman de la Rose in its entirety on the World Digital Library

Susan Groag Bell, “Christine de Pizan in Her Study,” Cahiers de recherches médiévales et humanistes [En ligne], Études christiniennes, mis en ligne le 10 juin 2008, consulté le 18 juillet 2019.

Susan Groag Bell, The Lost Tapestries of the City of Ladies: Christine de Pizan’s Renaissance Legacy (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2004).

Charlotte E. Cooper, “Ambiguous Author Portraits in Harley MS 4431,” in Performing Medieval Text, ed. Ardis Butterfield, Henry Hope, and Pauline Souleau, 89–107 (Cambridge: Legenda, 2017).

Sandra Hindman, Christine de Pizan’s ‘Epitre Othea’: Painting and Politics at the Court of Charles VI (Wetteren: Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies, 1986).

Nadia Margolis, An Introduction to Christine de Pizan, New Perspectives on Medieval Literature: Authors and Traditions (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2012).

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun, The Romance of the Rose, trans. Frances Horgan (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009).

Christine de Pizan, The Book of the City of Ladies (London: Penguin Classics, 2000).

Christine Sciacca, Illuminating Women in the Medieval World (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2017),