The “Plus Ultra” motto of the Spanish Empire in the emblem of Charles V of Spain, Town Hall of Seville, begun 1526 (photo: Ignacio Gavira , CC BY-SA 3.0)

We often think of globalization as a modern phenomenon, but the confluence of cultures we see today was already growing in the Spanish Empire during the 15th and 16th centuries. For instance, dividing screens from Japan were imported to Mexico, where they were used in colonial Spanish homes. Chocolate and tomatoes from Mexico and Central America made their way to Spain, where they enlivened the cooking of royal chefs. Spain, with its territory reaching from Europe to the Philippines, soon amassed a huge amount of wealth, and consequently became not only a center for art patronage (the commissioning of artworks), but also a place where imported materials, goods and ideas fostered new approaches to art.

Diversity and dominance

For much of the Middle Ages, Spain had been home to three dominant religions: Islam, Christianity, and Judaism. The convivencia , or coexistence, of These groups Characterized Spain During this period. The coexistence ultimately ended in 1492, when the Catholic monarchs Ferdinand and Isabel of Castile toppled the last Muslim stronghold in Granada and expelled the Jews from the Iberian Peninsula. However, many Muslims and Jews remained and were converted (some forcibly) to Christianity, at which point they became known as moriscos and conversos .

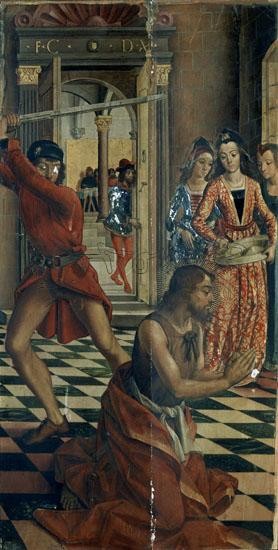

Ferdinand and Isabella also established the Inquisition, a Catholic institution whose job it was to root out Heresy. The officials responsible were highly suspicious of the newly converted, and numerous records attest to the persecutions, imprisonments, and occasional burnings undertaken by the Inquisition. A painting by Pedro Berruguete shows an auto-da-fe (“act of faith”): a ceremony in which someone was accused and then punished by inquisitors. Despite these persecutions, moriscos and conversos retained elements of their previous practices and continued to contribute to the cosmopolitan nature of Spanish society.

Pedro Berruguete, Auto da Fe Presided Over by Santo Domingo de Guzman, c. 1495, oil on panel, 154 x 92 cm (Museo del Prado, Spain)

1492 was also a remarkable year because it was the moment that Christopher Columbus discovered that the world was much larger than Europeans had previously believed. His expeditions to the Americas, and the often destructive colonization and evangelization that followed, helped the Spanish monarchs to amass a great fortune based on indigenous labor and natural resources. By the mid-sixteenth century, the Spanish controlled an impressive amount of land throughout the Americas, and large urban centers had been established in Peru, Mexico, and Hispaniola (today the Dominican Republic)—to name few—all the result of the conquest of local indigenous populations like the Inka and the Aztec. The Spanish viceroyalties eventually grew to encompass much of the Americas as well as the Philippines, making for a truly diverse and global empire.

Itinerant artists, traveling ideas

During the Renaissance, the Spanish empire also extended throughout Western Europe. The dominant ruling family during this time was that of the Hapsburgs, including the powerful Charles V, who became Holy Roman Emperor in 1516 after the death of Ferdinand and Isabel, and was succeeded by his equally influential son Philip II in 1556. Given Spain’s political reach in Europe, it is not surprising that Spanish Renaissance art displays influences from Flanders and Italy. Artists from around Europe traveled to the Iberian Peninsula to seek favor with the Spanish court, and artworks flowing in from other parts of the empire influenced artists already working in Spain.

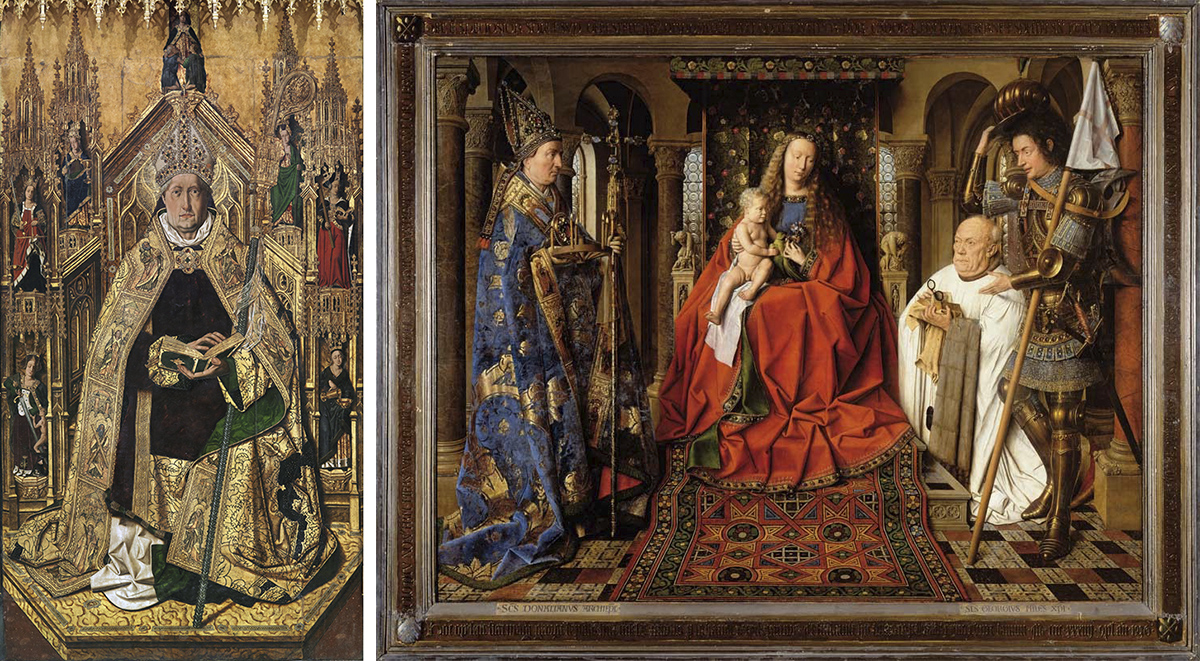

Left: Bartolomé Bermejo, Saint Dominic of Silos enthroned as a Bishop, 1474-77, oil on panel, 242 x 130 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid); right: Jan van Eyck, The Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele, 1434-36, oil on wood, 141 x 176.5 cm (Groeningemuseum, Bruges)

During the fifteenth century, prior to and during the reign of Ferdinand and Isabel, the influence of Flanders was felt most strongly. Artists like Bartolmé Bermejo and Fernando Gallego exemplify what is referred to as the Hispano-Flemish style, or the combination of Spanish and Flemish elements. In Bermejo’s Santo Domingo de Silos, for instance, the saint sits on an elaborate throne wearing golden robes executed in great detail. Like many Flemish paintings of this period, the work is a feast for the eyes with its ornateness, opulence, and attention to detail. The saint’s crumpled drapery also reveals Flemish influences.

Northern Renaissance paintings, tapestries, and other kinds of artworks bought by wealthy Spanish collectors also influenced art in Spain. Prints (for instance, engravings by Northern Renaissance artists such as Albrecht Dürer or Martin Schonguaer) circulated throughout Spain and influenced artists like Bermejo. Some of the most famous Flemish painters traveled to Spain or had their works collected by Spanish patrons. Jan van Eyck journeyed to the Iberian Peninsula in 1428–29. He and Rogier van der Weyden, and many other Flemish painters also regularly sent paintings to patrons in Spain. Spanish royalty collected many well-known paintings at this time (many of which are now on view in the Museo del Prado in Madrid), including Hieronymous Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights, Dürer’s 1498 Self Portrait, and Titian’s Bacchanal of the Andrians, which also influenced courtly tastes and the direction of Spanish art.

Italian artistic ideas and motifs are also noticeable in Spanish painting and sculpture. These influences can be seen in works like Berruguete’s Beheading of the Baptist from c. 1490 in the parish church of Santa Maria del Campo, in which the black-and-white tiled floor recedes into the background, creating illusionistic sense of space, complete with classicizing architectural elements—all of which are hallmarks of the Italian Renaissance. Nevertheless, the complex nature of Spanish art is simultaneously revealed in this painting, because it also includes “Hispano-Flemish” characteristics like the stylized drapery.

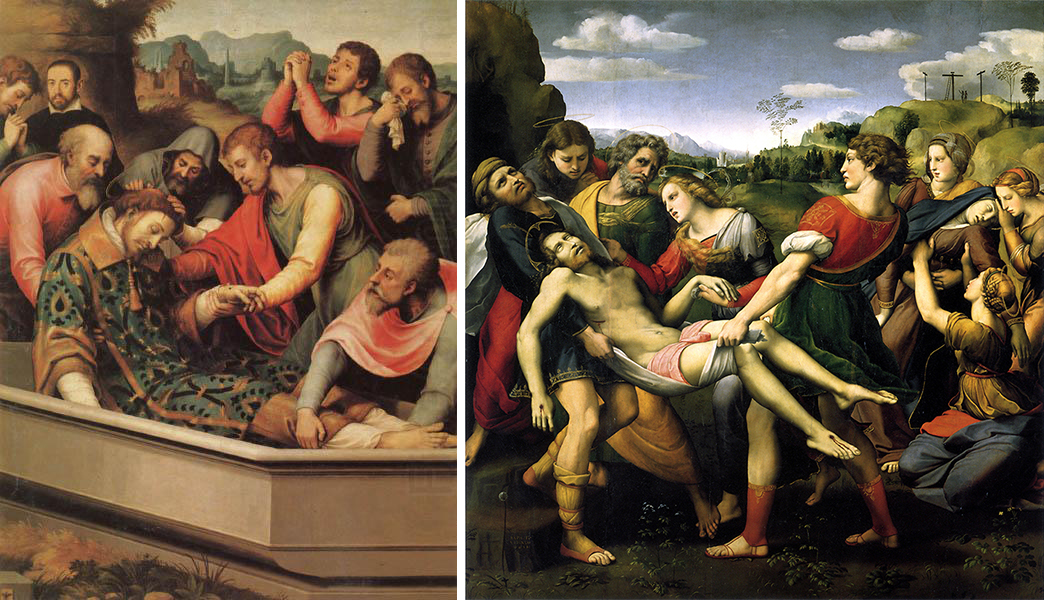

Left: Joan de Joanes, The Burial of Saint Stephen, c. 1562, oil on panel, 160 x 123 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid); right: Raphael, The Entombment, 1507, oil on wood, 184 × 176 cm (Galleria Borghese, Rome)

Luis de Morales, The Virgin Nursing the Child, 1560-65, oil on panel, 38 x 28 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid)

Other Italianate influences on Spanish art appear in the paintings of Joan de Joanes and Luis de Morales. Joanes was inspired by Raphael’s lyricism and gracefulness, and sometimes directly quoted from Raphael’s artworks. Luis de Morales painted multiple devotional paintings of Christ and the Virgin Mary, many of which show the artist’s adaptation of Leonardo da Vinci’s sfumato and Mannerist elements, including elongated bodies and faces. Spanish artists like the sculptor Alonso Berruguete (son of Pedro Berruguete) sometimes traveled to Italy for training, but many only encountered Italian art that was displayed in Spain or through prints or copies of Italian artworks.

Juan Bautista de Toledo (architect), El Escorial, 1563-84 (San Lorenzo de El Escorial, Spain) (photo: Monasterio Escorial, CC BY 2.0)

The Court of Philip II

Pompeo Leoni, Retablo Mayor, Basilica de El Escorial, 1579-88 (photo: José Luis Filpo Cabana, CC BY 3.0)

During the reign of Philip II in the later sixteenth century, Spanish art shifted away from the “Hispano-Flemish” mode that had been popular earlier. Philip II favored several artists, among them the revered Titian, who sent portraits of the Hapsburg ruler from his studio in Venice. Other court artists, including Alonso Sánchez de Coello and Sofonisba Anguissola, painted portraits of court members, fulfilling Philip II’s desire to visually represent the power of his imperial court. Philip II also sponsored the construction of the Escorial, an immense complex that comprises royal burials (including the body of Charles V), a royal chapel, and a seminary. The plan is rigidly geometrical, and is defined by a giant, symmetrically subdivided square. The classical entrance bay is drawn from Italian Renaissance architecture, and the tower-flanked façade borrows from the French chateau style. The overall impression is austere and foreboding—an expression of Philip II’s fervent religiosity and imperial power. On the interior, numerous artists, some hailing from Italy, were commissioned to produce paintings, frescoes, sculptures, and tapestries to adorn this monumental space.

Juan de Juni, Burial of Christ, c. 1541-44, polychromed wood (Museo Nacional de Escultura, Spain)

Drama in wood

We typically associate materials like marble and bronze with Renaissance sculpture—not polychromed (multicolored) wood. Yet in Spain, painted and gilded (gold-covered) wooden sculpture was immensely popular, and sculptors who worked in wood, like Juan de Juni, Alonso Berruguete, and Diego de Pesquera, were well-known in their heyday. After the sculptor crafted the figures, typically another artist would paint the sculpture. This was often done using the time-consuming estofado technique, which involved layering gold or silver leaf onto the wood, then painting over it to create a brilliant surface. Sometimes the artist would remove layers of paint to reveal the metallic materials beneath.

In 1544, Juni completed his Burial of Christ for the lower level of an altarpiece. It is a large figural grouping, carved from wood and painted, and portraying six life-sized individuals grieving over Christ’s dead body on a sepulcher. These figures include Christ’s mother, John the Evangelist, Mary Magdalene, Mary Cleophas, Nicodemus, and Joseph of Arimathea. Though Juni originally hailed from Burgundy, France, here he created classicizing, naturalistic bodies that reflect the adaptation of Italian artistic trends.

A clash of beliefs

Even as Humanist ideas spread throughout Charles V’s Spain, the sixteenth century was also a time of religious controversy and reform. Catholicism found itself threatened by Protestantism, which had been taking hold in northern Europe since Martin Luther’s Reformation in the early decades of the century. In Spain, the Inquisition investigated groups thought to be unorthodox or subversive (such as the moriscos and conversos), including ones too closely aligned with Lutheran thinking.

Many of the artworks during the reign of Philip II responded to the Council of Trent, where Catholic officials re-emphasized the significant role that art could play in moving the faithful to piety—particularly in response to Protestant criticisms. Domenikos Theotokopoulos, better known as El Greco, is a key example of an artist who understood the power that images could have to move souls, and his emphatic religious work was welcomed in Spain.

El Greco, The Savior, 1608-14, oil paint, 100.4 x 80.2 cm (Museo del Greco, Toledo)

El Greco was trained on the Greek island of Crete, where he painted icons in the Byzantine tradition. He then traveled to Italy, where he absorbed the influences of Tintoretto and others before finding work in Toledo, Spain. El Greco’s The Savior provides a fitting end to this short essay on the artistic influences that shaped visual culture in Renaissance Spain. The painting not only displays the mannerist, mystical tendencies in Spanish art that were absorbed by this Cretan artist, but also speaks to the globalized Spanish Empire: the red glaze on Christ’s tunic comes from the crushed cochineal bug, acquired from Spain’s American colonies and exported to the Iberian Peninsula to be traded around the world. Renaissance Spain was truly eclectic.

Additional Resources:

Pedro Berruguete’s Auto da Fe Presided Over by Santo Domingo de Guzman at the Museo del Prado

Bartolomé Bermejo’s Saint Dominic of Silos enthroned as a Bishop at the Museo del Prado

Images of a Burgundian cope (cape worn by a priest)

Joan de Joanes’s The Burial of St. Stephen at the Museo del Prado

Luis de Morales, The Virgin Nursing the Child at the Museo del Prado