Carlo Crivelli, The Annunciation with Saint Emidius, 1486, egg and oil on canvas, 207 x 146.7 cm (The National Gallery, London)

Carlo Crivelli, The Annunciation with Saint Emidius, 1486, egg and oil on canvas, 207 x 146.7 cm (The National Gallery, London)

Aside from Cosimo Tura, Carlo Crivelli was the most delightfully odd late Gothic painter in Italy. Born in Venice, he absorbed the influences of the Vivarini, the Bellini, and Andrea Mantegna to create an elegant, profuse, effusive, and extreme style, dominated by strong outlines and clear, crisp colors—perhaps incorporating just a whiff of early Netherlandish manuscript style. By 1458 he had left Venice to work in the Marches (the fertile plains south of the Appenines) in and around the port city of Ancona on the Adriatic. As a seaside painter, he could be credited with inventing a second Adriatic style that stands in stark contrast to the soft, suffused colors and gentle contours of Giovanni Bellini.

Carlo Crivelli, detail of The Annunciation with Saint Emidius, 1486, egg and oil on canvas, 207 x 146.7 cm (The National Gallery, London)

The subject matter

This Annunciation is signed and dated 1486, so it was an early commission in his adopted territory. The narrative is deceptively simple; the angel Gabriel interrupts the Virgin, engaged in reading and prayer, to announce that she will become the mother of the son of God. The actual event, the incarnation, occurs through words rather than actions, and to be recognizable as a dramatic encounter there are a variety of poses that the Virgin assumes to signify her reaction, from humble acceptance to visible consternation. Crivelli’s version rather peculiarly places Gabriel outside the Virgin’s home, accompanied, in another unusual variation on the theme, by St. Emidius.

Gabriel and St. Emidius (detail), Carlo Crivelli, The Annunciation with Saint Emidius, 1486, egg and oil on canvas, 207 x 146.7 cm (The National Gallery, London)

Emidius is the patron saint of the town of Ascoli Piceno, and Crivelli painted this altarpiece for the city’s church of the Santissima Annunciazione (the Holy Annunciation). A proud citizen, Emidius seems to have hurried to catch up to Gabriel to proudly show off his detailed model of the town, which he holds rather gingerly, as though the paint hasn’t quite dried.

The fact that Gabriel and the Virgin do not share the same space is unusual, but doesn’t seem to disrupt the delivery of the message. We see the descent of the Holy Spirit has penetrated the frieze of the building, through a conveniently placed arched aperture, into the room where Mary kneels receptively. The inclusion of Emidius brings the miracle of the incarnation home, and this corner of the city is depicted in the kind of deep perspective of contiguous spaces that one sees later in Dutch Baroque domestic scenes, such as Pieter de Hooch’s At the Linen Closet.

Carlo Crivelli, detail of The Annunciation with Saint Emidius, 1486, egg and oil on canvas, 207 x 146.7 cm (The National Gallery, London)

The variety of figures in the background on the left of the painting lend an atmosphere of spontaneity and the hubbub of everyday life; at the top of the staircase a little girl peeks around a column, a group of clerics are engaged in conversation and, in the upper mid-ground, two figures stand on the footbridge above the arch, one reading a just-delivered message (echoing the Annunciation).

Carlo Crivelli, detail of The Annunciation with Saint Emidius, 1486, egg and oil on canvas, 207 x 146.7 cm (The National Gallery, London)

The inscription along the base of the painting reads “Libertas Ecclesiastica” (church liberty), and refers to Ascoli’s right to self-government, free from the interference of the Pope, a right granted to the town by Sixtus IV in 1482. The news reached Ascoli on 25 March, the Feast of the Annunciation, which is probably the message the official in black is reading.

Carlo Crivelli, detail of The Annunciation with Saint Emidius, 1486, egg and oil on canvas, 207 x 146.7 cm (The National Gallery, London)

Carlo Crivelli, detail of The Annunciation with Saint Emidius, 1486, egg and oil on canvas, 207 x 146.7 cm (The National Gallery, London)

To the right of the two figures on the bridge, the bases of a crate and a potted plant extend out over the wall just far enough to suggest they could, with a little nudge, topple onto the head of a figure below who, oblivious, shades his eyes to better see the penetrating irradiation of the Holy Spirit entering the wall. He is the witness inside the painting, we are the witnesses outside the painting.

The spatial composition of the overall painting is actually quite traditional, hearkening back to the Annunciation fresco of Piero della Francesca at the church of San Francesco in Arezzo; in both the surface of the painting is essentially vertically bisected by the architecture, while the right half is squared by the horizontal division between the lower room and upper balconies of the Virgin’s dwelling. What is spectacularly different here is Crivelli’s architectural articulation, which consists of an entire dictionary of all’antica elements, made more dramatic by the profusion of materials from which the buildings are made.

The white columns carry gilded capitals, the entablature is elaborated by a red marble frieze, both are illusionistically “carved” with running reliefs of floral, vegetal, and acanthus decoration, springing from beautiful vases, and the frieze is further punctuated with putto heads, lending a sense of animation to the scene. Adding to the ornamentation are egg-and-dart and curious floral dentils, varied marbles, a carved imperial profile relief encircled by a wreath, and crenellations along the farthest wall.

Carlo Crivelli, detail of The Annunciation with Saint Emidius, 1486, egg and oil on canvas, 207 x 146.7 cm (The National Gallery, London)

Luxurious costumes

All the major characters wear luxurious costumes, painted to resemble gold and silver embroidered brocades. Gabriel wears a large gold medallion, on a heavy chain, studded with cabochon jewels. Emidius wears a bishop’s mitre similarly jeweled, with a large jeweled clasp on his golden cope. The Virgin wears a jeweled head-band and a dress modestly trimmed with pearls along the top of the bodice. Gabriel’s feathered epaulettes echo his glorious wings, which deserve an essay of their own. The elegant delicacy of Crivelli’s linear style can be seen best in the elongated, pale hands of the Virgin, floating at the ends of her arms, lightly folded across her breast in supplication.

A splendid interior

Rather than occupying a sparsely furnished monastic cell, the Virgin is depicted in a splendidly arrayed interior that echoes the magnificence of the palace exterior. Red and green pillows and blankets embroidered with gold thread cover her bed, with its sweep of red silk curtain, similarly embroidered in gold.

Carlo Crivelli, detail of The Annunciation with Saint Emidius, 1486, egg and oil on canvas, 207 x 146.7 cm (The National Gallery, London)

The objects on the shelf above the bed are made of a variety of materials, from the gold candle holder to the barely fluted glass carafe which holds clear water, a sign of Mary’s purity. The grain of the wood in the prie-dieu runs vertically, in contrast to the horizontal grain of the base of the bed, which helps to create the shallow recession in which the Virgin kneels on a splendid carpet.

Carlo Crivelli, detail of The Annunciation with Saint Emidius, 1486, egg and oil on canvas, 207 x 146.7 cm (The National Gallery, London)

A sense of cosmopolitanism

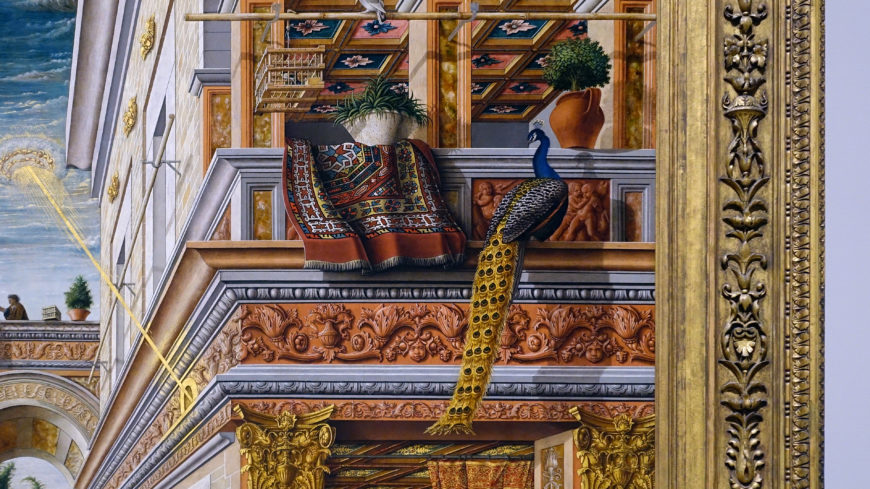

At the level of the balcony, Crivelli draws our eye to another carpet, this one displayed draped over the balustrade, and yet another is draped above the arch in the background. Carpets such as these were a major Italian import from the eastern Mediterranean, and used here they lend a cosmopolitan air to the city. The presence of a splendidly feathered peacock, another exotic import, reminds us that carpets from the eastern Mediterranean were coveted luxury items brought in through trade, and they lend an air of cosmopolitanism to the overall scene.

Carlo Crivelli, detail of The Annunciation with Saint Emidius, 1486, egg and oil on canvas, 207 x 146.7 cm (The National Gallery, London)

A pickle and an apple?

Of course, the objects that attract the most attention in this painting are the cucumber and apple, placed right in the center foreground of the painting, above the inscription. The cucumber, in fact, seems to project out of the painting and teeter into our space, breaking the fictive wall and blurring the line between a space of miracles and our everyday world. The apple can be taken to symbolize original sin, the source of our fall, the forbidden bite setting into motion the whole reason for the Annunciation. In all fairness, the National Gallery calls the cucumber a gourd (which does sound more Biblical), since cucumbers are part of the gourd family, and leaves it at that, there being neither a Holy Cucumber nor a Holy Gourd. Alas, here we enter the realm of speculation. One school of thought, absent any evidence, is that apples symbolize female sin and cucumbers symbolize male sin. I’ll leave it to you to work out why. Could it be a marrow? Marrows do appear in the Bible, as in Psalm 63:5: “My soul shall be satisfied as with marrow and fatness; and my mouth shall praise thee with joyful lips.” That seems rather appropriate. The controversy rages on.

Additional resources:

This painting at The National Gallery

Learn more about the expanding the renaissance initiative

Stephen John Campbell, C. Jean Campbell, Francesco De Carolis, Ornament and Illusion: Carlo Crivelli of Venice (Paul Holberton Publishing, 2015)

Ronald Lightbown, Carlo Crivelli (Yale University Press; 1st Edition edition, 2004)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”CrivelliNG,”]

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:04] We’re in The National Gallery in London, looking at a large painting by Carlo Crivelli, who comes originally from Venice.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:11] He’s associated with a region on the eastern coast of Italy known as The Marches.

Dr. Zucker: [0:16] He’s one of my favorite artists. There’s something incredibly compelling about his attention to architecture, to material culture.

Dr. Harris: [0:25] The kind of hard-edged realism that makes everything almost pop out and move into our space, but he’s clearly a master of perspective, so we’re pulled in at the same time.

Dr. Zucker: [0:37] The surface of this canvas is almost bejeweled. It’s so decorative.

Dr. Harris: [0:41] The ornament, the jewels, the gold, even the bricks and the marble, he’s clearly showing off his skill as a painter, and in that way making us aware of the incredible craftsmanship of the art of painting.

Dr. Zucker: [0:54] It’s so focused on the particular that it takes a moment to locate the subject, which in this case is an Annunciation.

Dr. Harris: [1:01] When the angel Gabriel announces to Mary that she will bear Christ, that God will be made flesh and she will be the mother of God.

Dr. Zucker: [1:09] In a traditional Annunciation, we see the archangel Gabriel almost always on the left, kneeling, having just landed. We see here Gabriel’s wings are still outstretched. To the right, we see the Virgin Mary, and she’s inevitably shown reading the Bible.

Dr. Harris: [1:25] We have very typical Annunciation iconography here. The angel Gabriel raises his hand, greeting the Virgin Mary. In his left hand, he holds a lily, a symbol of Mary’s virginity, her purity. On the right, the Virgin Mary accepting the message of the angel Gabriel, her hands folded in front of her, this expression of her humility. All of that makes sense, but we have a third figure.

Dr. Zucker: [1:49] I can’t remember another Annunciation scene where a third figure was taking such an active role.

Dr. Harris: [1:56] This is Saint Emidio, the patron saint of Ascoli, and the convent that this painting was made for is located in that city. He’s attempting to engage Gabriel, and Saint Emidio holds a model of the city in his hands.

Dr. Zucker: [2:11] This painting was a commission that was meant to commemorate a very important event in the city’s history. The city had been able to reach an agreement with the pope to cede to it a local political autonomy, which was enormously important to the city.

Dr. Harris: [2:25] It was a freedom under the protection of the pope, and we can see that clearly in the bottom inscription, which says “Libertas Ecclesiastica.”

Dr. Zucker: [2:33] This painting was commissioned to commemorate that freedom.

Dr. Harris: [2:37] Along the top of the triumphal arch, we see a papal messenger giving this document that announces the freedom of the city to an official.

[2:47] The critical thing here, though, is that the people of the city received this news from the pope on the holiday that honored the Annunciation.

Dr. Zucker: [2:56] So there was this clear connection in the minds of the townspeople between the Annunciation and the freedom that they had gained. This painting is bringing those two things together, and in fact, every year a procession was held to commemorate the gaining of this freedom. The procession would end at this painting.

Dr. Harris: [3:14] We see also the life of the city, some Franciscan monks and people, some rich, some poor.

Dr. Zucker: [3:21] This painting is filled with objects. Many of them have symbolic meaning.

Dr. Harris: [3:25] For example, we see a bird in a cage. That’s a goldfinch, a symbol of Christ’s death on the cross, his sacrifice for mankind.

Dr. Zucker: [3:34] There are also other birds. There’s this incredible peacock. Look at the decorative quality of the pattern of the tail. The peacock is a symbol of immortality, of the idea of the Resurrection.

Dr. Harris: [3:45] That cucumber and apple in the foreground.

Dr. Zucker: [3:48] The apple is easy enough to read. The apple is generally the fruit from the Tree of Knowledge, the forbidden fruit that Adam and Eve ate.

Dr. Harris: [3:57] The apple is about their fall from grace with God. That refers back to the scene that we see before us because it’s Mary and Christ who, in a way, fix that Original Sin caused by Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden by Christ’s sacrifice.

[4:14] The cucumber is filled with seeds, and because it’s filled with seeds, it’s a symbol of the Resurrection, of the idea of life after death, the central miracle of Christianity.

Dr. Zucker: [4:27] We see the golden light of heaven that pierces the wall of the house so that it can enter and make its way to the Virgin Mary. And we see a white dove, the Holy Spirit.

[4:37] There is a kind of conflict here. A conflict between the idea of the sacred and the wealth that’s being expressed in this painting. Mary, who we know was very poor, and yet she’s living in a house that couldn’t be more lavish. It’s filled with expensive objects, with gold.

Dr. Harris: [4:52] She kneels on a Persian carpet. There’s another Persian carpet in the loggia above. We’re reminded of the trading that was happening in this region.

Dr. Zucker: [5:02] And so there are two parts to this, one is that there were medieval traditions that understood Mary as being of royal lineage. The other part of it is that the worldly possessions are seen as a symbolic way of representing her divinity.

[5:16] In order to read this painting, we need to understand not only the story of the Annunciation but the traditions of how that story is painted, and we need to have some specific understanding of the circumstances under which this particular painting was made.

[5:30] When we look at the extraordinary work of an artist like Crivelli, I think it prompts us to think about why we focus almost exclusively on painting made in Florence or Venice.

[5:42] I think part of the problem is the way that art history itself was written at the end of the 19th and through the 20th century. It does a disservice to the more complex reality that existed in what we now call Italy.

Dr. Harris: [5:53] It’s important for us to see Italy as connected to the Adriatic Sea, and therefore to the Ottoman Empire, and Europe as an interconnected place, many artists who moved and served patrons in different places the way that Crivelli did, and to be able to really appreciate more work from the Renaissance than the usual superstars that we see.

[6:19] [music]