In Ryan Coogler’s 2018 film, Black Panther, the supervillain Erik Killmonger goes to a fictional museum—The Museum of Great Britain. While there, he meets with the curator of African art. Killmonger challenges the curator on her introduction of one of the African objects, asserting that “it was taken by British soldiers in Benin, but it’s from Wakanda [a fictional African nation in the film], and it’s made of vibranium [a fictional metal].” He further astonishes the curator when he casually says that he will “take it off [her] hands.” The curator declares, “These items aren’t for sale.” Killmonger then asks: “How do you think your ancestors got these? You think they paid a fair price? Or did they take it, like they took everything else?”

This exchange points to an actual moment in Britain’s colonization of West Africa: the violent destruction and looting of Benin City, the capital of the Kingdom of Benin (currently, Benin City is the capital of Edo State in present-day southern Nigeria).

During the 1897 attack, the British stole an estimated 10,000 objects made of copper alloy (plaques and other artworks), carved and uncarved ivory, works made of wood and coral, and human remains (such as skulls and teeth). Today, these objects are known collectively and loosely as the Benin “Bronzes,” and are displayed or stored globally in museums and galleries, private and family collections, and other institutions. [1] Originally, the plaques were displayed in the audience courtyard of the Oba’s (king’s) palace. The plaques were commissioned and created during the reign of two kings, Oba Esigie and his son, Oba Orhogbua. Sometime during the 17th century, the plaques were taken down. The British found them in an otherwise empty building in the Oba’s compound during the invasion of the city.

The violent sacking and pillaging of Benin City, (usually referred to as the Benin Expedition or the Punitive Expedition of 1897), had been framed in British newspaper articles of the time as a justified act of retaliation in response to another episode: the Phillips Expedition.

Artist unidentified, Relief plaque showing four page figures in front of palace compound, courtyard or altar entrance with high tiled roof and turret, c. 16th–17th century, brass, from Benin City, Edo Kingdom, Nigeria, 55 x 39 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

The Phillips Expedition

In June 1896, the Niger Coast Protectorate (NCP) appointed James Robert Phillips as its Deputy Commissioner and Consul. The British claimed Benin City was within the NCP’s domain, and tried multiple times (beginning in 1862) to get the reigning Oba (king) to sign a trade treaty that would give the British access to commodities in the area. In March 1892, the king at the time, Oba Ovonramwen, signed a trade treaty with the British. Marking the treaty with an ‘X’, it is unclear to what extent Oba Ovonramwen understood the conditions of the treaty, as multiple individuals served as translators.

Ultimately, NCP officials regarded Oba Ovonramwen as an obstacle to British access to trade commodities such as palm kernels, as they perceived that the king was not fulfilling his part of the agreement. To force Oba Ovonramwen to comply with the conditions of the trade treaty (which were far more advantageous to the British), Phillips requested permission from the British government to send an armed force to Benin City. In an effort to have his request fulfilled, he added that the vast amounts of ivory in Benin City would help to pay for the costs of the armed force.

Artist unidentified, altar tusk, 16th–19th century, carved elephant ivory (Benin City, Edo Kingdom, Nigeria), 116.5 x 9 x 8 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

After this request was denied by the Foreign Office, Phillips led (without permission) an expedition of nine British men and an estimated 200–250 carriers in January 1897. [2] When Phillips’ party reached Gwato, they received warnings that any white man who approached Benin City would be killed. Phillips’ party was on their way to Benin City during the Ague festival, or festival of yams. Since the Ague festival required that the Oba refrain from certain practices, such as meeting with foreigners, he was restricted from receiving the Phillips’ party. [3] Not heeding the warnings, the Phillips’ expedition continued with their mission. All of the British participants, except for two, were killed. It is unclear how many carriers were also killed. [4]

This incident, known as the Phillips Expedition, has been framed as the main impetus for the violence perpetrated by the British soon after. However, a few months after Oba Ovonramwen signed the trade treaty in 1892, NCP officials had expressed their desire to depose him. Accusing the king of hindering trade with the British, NCP officials wanted to be rid of Oba Ovonramwen nearly five years before the Phillips Expedition. NCP officials perceived that the Oba’s authorization of human sacrifices and other practices (which the British referred to as “fetishes” or “juju”) caused certain commodities to be taxed heavily or to be restricted from being traded. The British would use the existence of human sacrifice as another reason to justify their attack on Benin City. [5] The ambush of Phillips and his party (it is unclear how many non-British participants were injured and killed) gave the British a justification to finally remove Oba Ovonramwen and to destroy Benin City.

![Reginald Kerr Granville, Interior of King's compound burnt during fire in the siege of Benin City, with three British officers of the Punitive Expedition [from left, Captain C.H.P. Carter 42nd, F.P. Hill, unknown], seated with bronzes laid out in foreground, 1897, photograph, 16.5 x 11.5 cm (Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford University)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/destroyed-palace-870x635.jpg)

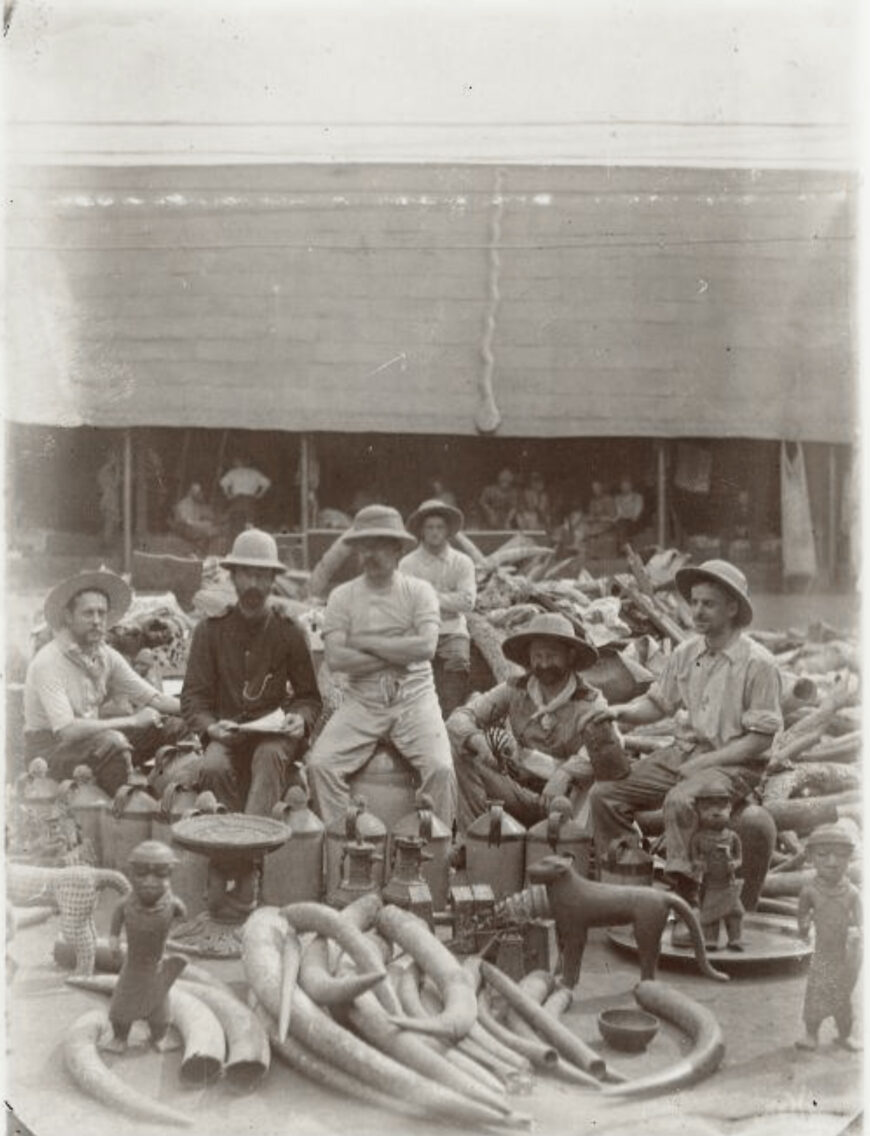

Reginald Kerr Granville, Interior of King’s compound burnt during fire in the siege of Benin City, with three British officers of the Punitive Expedition [from left, Captain C.H.P. Carter 42nd, F.P. Hill, unknown], seated with bronzes laid out in foreground, 1897, photograph, 16.5 x 11.5 cm (Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford University)

The Punitive Expedition at Benin City

Newspapers informed the British public about the Phillips Expedition days after it occurred, and reported that a punitive expedition was a likely response. On January 13, 1897, Vice Admiral Harry Rawson was appointed to lead an immense force to Benin City: an estimated 1,400 soldiers and 2,500 carriers, along with NCP staff, medics, and scouts. [6]

The Punitive Expedition of 1897 took place between February 9 to 27. During this 3-week campaign, the British machine-gunned, bombarded, and torched villages and towns, and indiscriminately massacred countless Edo people, the inhabitants of the Kingdom of Benin (and present-day Edo State). It is unknown what the death toll was. On February 18, the British took Benin City. They destroyed buildings, homes, and palaces, desecrated sacred sites, and blew up a sacred tree. The British believed that they were cleansing the city and breaking the power associated with “fetishes” or “juju” through these acts of demolition and vandalization. During their attack, the British also looted the wide range of objects referred to as the Benin “Bronzes.”

Photographer unidentified, members of the British expedition to Benin City with objects from the royal palace, 1897, gelatin silver print, 16.5 x 12 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Dan Hicks, Curator of World Archaeology at the Pitt Rivers Museum, reminds us that besides taking objects from Benin City, the British also took photographs. In one of the most well-known and circulated photographs from this expedition, we see six men sitting among a massive array of looted objects. In the foreground, we see a pile of elephant tusks (uncarved ivory), a bowl, bells, statues of leopards and people, and other objects (likely a stool and jugs or jars). In the middle ground, the men sit comfortably (several look at the camera). The man to the far right holds a statue of a head against his right leg. Behind the men is a large pile of loot (numerous elephant tusks) and perhaps debris from the destruction of the city. The background is blurry, but people can be seen underneath the roof of a building. Slightly towards the right of the roof, a copper alloy-casted snake appears to slither down.

Oba Ovonramwen escaped during the invasion of Benin City, but surrendered himself to the British in August 1897. He was put on trial for the killing of Phillips and his party, but was not found guilty. However, six other chiefs were convicted. [7] Oba Ovonramwen was exiled to Calabar, where he lived until his death in 1914.

Artist unidentified, Relief plaque, 16th–17th century, Benin City, Nigeria, brass, 46.5 x 37.5 x 11 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Artist unidentified, Relief plaque, 16th–17th century, Benin City, Nigeria, brass, 46.5 x 37.5 x 11 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

The Punitive Expedition at Benin City was not an isolated incident, as other punitive expeditions were led by the British in present-day Nigeria (Brohemie, 1894; Brass, 1895; Ediba, 1896; Agbor, 1896; and Cross River, 1896). These expeditions were also characterized by the burning of villages and towns, the desecration of sacred spaces, the displacement and murder of Indigenous peoples, and overthrow or murder of local chiefs or kings seen as impediments to British control. The Punitive Expedition at Benin City should be understood not as an anomaly, but as part of a recurring pattern in which the British used violent means to conquer lands that they claimed for themselves and to terrorize and subdue their inhabitants.

Display and interpretation of Benin “Bronzes”

Within months of the Punitive Expedition at Benin City, some of the stolen loot was displayed in various museums in London. For example, 300 plaques were loaned to the British Museum and exhibited. Charles Hercules Read and Ormonde Maddock Dalton, the Keeper and Senior Assistant in the British Museum’s Department of British and Medieval Antiquities and Ethnography respectively, praised the beauty and sophistication of the plaques. Regarding them as works of art, Read and Dalton acknowledged that their makers possessed remarkable experience, knowledge, and technical skill on par with Italian Renaissance artists. Similarly, Felix von Luschan, Assistant Director at the Königliches Museum für Völkerkunde in Berlin, promoted the metalwork and ivory as art. He invoked the highly-esteemed, skilled craftsmanship associated with the Italian Renaissance sculptor and goldsmith, Benvenuto Cellini, to describe the casting employed. However, in spite of their great admiration for the Benin art and material culture, Read and Dalton posited that the fabrication of the plaques could not have been made by the contemporary Edo people, whom they described as “barbarous.” [8] Like other British contemporaries, Read and Dalton perceived Benin City to be in a state of “degeneration.” [9]

Artist unidentified, Relief plaque (Portuguese soldier, detail), c. 16th–17th century, copper alloy, from Benin City, Edo Kingdom, Nigeria, 47 x 31 x 9 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Artist unidentified, Relief plaque (Portuguese soldier), c. 16th–17th century, copper alloy, from Benin City, Edo Kingdom, Nigeria, 47 x 31 x 9 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Based on the representations of Europeans (including their manner of dress and weapons) on the plaques, Read and Dalton asserted that they were made in the middle of the 16th century, and speculated (incorrectly) that the Portuguese taught or helped the Edo to create these works. [10] Attributing the Benin works to the Portuguese reflects racist attitudes that deny the Edo as the rightful creators of their own art and material culture. Ese Vivian Odiahi, who has conducted interviews with members of the guild of casters, reminds us that casting is an “indigenous art” of the Kingdom of Benin, and the earliest guild of casters can be traced back to the reign of Oba Oguola in the 13th century. [11]

Returning the Benin “Bronzes”

Calls for the return of the Benin “Bronzes” have been issued since 1936, when Oba Akenzua II made the first formal request to the British Museum. G.M. Miller instructed the British Museum to return to Oba Akenzua II three items that he had loaned previously: “two coral crowns and a coral bead garment.” [12] Today, museums, galleries, and other institutions that have Benin “Bronzes” in their collections are grappling with what to do with them in the face of mounting diplomatic pressures, especially within the last decade, to repatriate or restitute them. Dan Hicks, who is working to return the Benin “Bronzes” in the Pitt Rivers Museum, makes clear, “the arrival of loot into the hands of western curators, its continued display in our museums and its hiding-away in private collections, is not some art-historical incident of ‘reception’, but an enduring brutality that is refreshed every day that an anthropology museum like the Pitt Rivers opens its doors.” [13]

Prince Gregory Akenzua, one of the great-grandsons of Oba Ovonramwen, asserts, “[the] artwork can be said to represent the history of the Benin people for centuries. It was taken from us. It was like ripping pages out of our history.” [14]