Benvenuto Cellini, Salt cellar, 1540-43, gold, enamel, ebony, and ivory, 28.5 x 21.5 x 26.3 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

When a thief broke into the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna in 2003, one object in particular caught his attention. The gallery lights glinted off an intricately worked gold and enamel surface—this was the famous salt cellar by the sixteenth-century Florentine sculptor and goldsmith, Benvenuto Cellini.

Benvenuto Cellini, Salt cellar, 1540-43, gold, enamel, ebony, and ivory, 28.5 x 21.5 x 26.3 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

This object takes the form of an oval base, on which two nude figures sit facing each other. Their smooth finish is the result of hours spent painstakingly hammering them into shape, while the ebony base was meticulously polished to shine like black marble. Some of the gold surfaces were enameled with carefully mixed, melted, colored glass, using a technique that the artist described as “a great art unto itself.” [1] The patron, French king Francis I, even placed a workshop of Parisian artisans at the artist’s disposal. No expense was spared on this laborious commission. Yet in the French court, the salt cellar would have been prized not just as luxury tableware, dispensing what were then expensive condiments, but as an intellectual conversation starter—filled with meanings waiting to be decoded by an elite, art-literate audience. All that glitters can be so much more than gold, as our dazzled thief would realize soon enough.

The ship held salt (left) and the temple held pepper (right). Benvenuto Cellini, Salt cellar, 1540-43, gold, enamel, ebony, and ivory, 28.5 x 21.5 x 26.3 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Land and Sea

In his autobiography, Cellini included an extensive description of the salt cellar that helps to shed light on its iconography and meanings. Cellini identifies the female nude as Tellus, the earth mother goddess, and the male nude as Neptune, god of the sea—and in a later description, simply as Land and Sea. Beside Neptune (or Sea) there is a small bowl in the form of a ship, designed to hold salt, while a temple beside Tellus, or Land, would have held pepper.

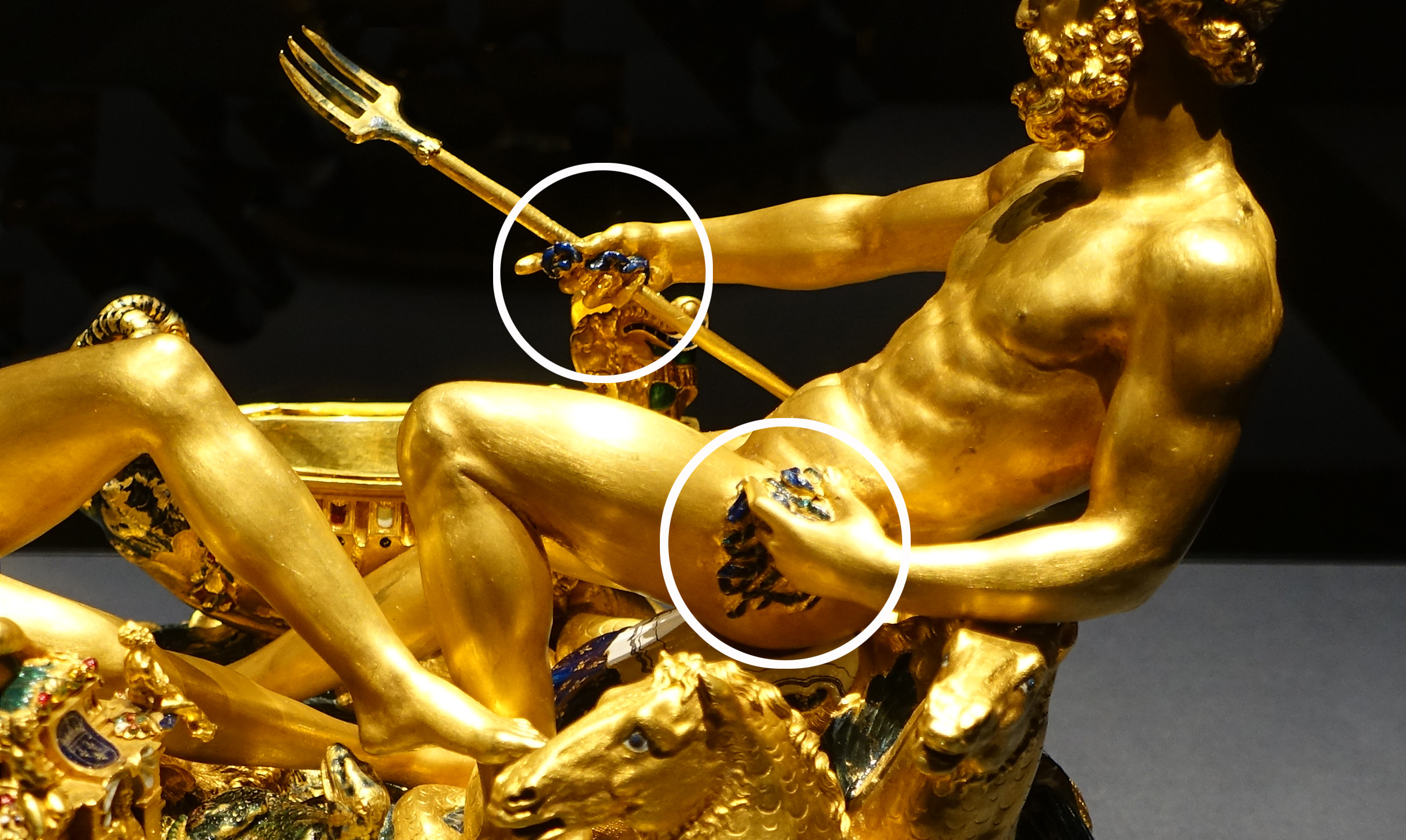

Reins circled in white. Benvenuto Cellini, Salt cellar, 1540-43, gold, enamel, ebony, and ivory, 28.5 x 21.5 x 26.3 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The male figure holds a trident in his right hand as well as reins defined with ribbons of blue enamel (the reins don’t actually connect to the sea-horses on either side of him). Sea-horses are common symbols of the tides since antiquity, and here they emerge from the waves surrounding him, along with other fish and sea creatures.

Tapered end of Horn of Plenty circled in white. Benvenuto Cellini, Salt cellar, 1540-43, gold, enamel, ebony, and ivory, 28.5 x 21.5 x 26.3 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The elephant is underneath Tellus. Benvenuto Cellini, Salt cellar, 1540-43, gold, enamel, ebony, and ivory, 28.5 x 21.5 x 26.3 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The female figure (Tellus, the earth mother goddess) has her right fingers resting on a horn of plenty at her side, an attribute often held by personifications of nature. With her left hand, she squeezes her breast, a gesture commonly used in sixteenth-century art to suggest fertility, wealth, and natural abundance. Tellus is surrounded by animals and flowers, and rests on an enameled, green hill draped with cloth displaying fleurs-de-lis.

The luxurious, foreign connotations of pepper, imported largely from India, are underscored by the elephant head and legs that emerge from the landscape on which Land sits. Elephants were associated with this south Asian location.

Elephant (detail), Benvenuto Cellini, Salt cellar, 1540-43, gold, enamel, ebony, and ivory, 28.5 x 21.5 x 26.3 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The poses of the two main figures relates to the production of salt. Cellini writes that Neptune and Tellus’s feet intertwine “just as we see some branches of the sea running into the land“. [2] Interlocking legs were often used to suggest a sexual relationship in renaissance art. This pose acts as an allegory for the origins of salt, then thought to be produced through the intermixing of substances from the sea and land. For a renaissance viewer, these figures of Land and Sea would have also suggested the elements of earth and water, two of the four materials from which all matter was thought to be made, along with fire and air, due to the popularity of humoral theory. Salt, pepper, gold and glass were considered members of the same family of materials, whose primary constituents were the elements, earth and water. All of Cellini’s materials reflect the union of the sea and the earth.

Two reclining figures and a personification of one of the four winds separated by tools and weapons on the base, Benvenuto Cellini, Salt cellar, 1540-43, gold, enamel, ebony, and ivory, 28.5 x 21.5 x 26.3 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

From a Cardinal to a King

This salt cellar was not originally designed for the French king, but for the Florentine Cardinal Ippolito d’Este, who ultimately stopped the commission when it threatened to become too expensive and time-consuming. When Francis I later requested that Cellini make him a ‘fine salt cellar’, he adapted these previous designs, most notably adding the base. [3]

Michelangelo, Dusk and Dawn, Tomb of Giuliano de’ Medici, 1526-33, marble, 630 x 420 cm (Sagrestia Nuova, San Lorenzo, Florence; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The base is decorated with four figures in reclining poses, which, according to Cellini, can be identified as Night, Day, Twilight and Dawn, and draw on Michelangelo’s statues of the same personifications for the Medici Tomb at the Sacristy of San Lorenzo in Florence. This reference placed his work in communication with one of the most highly praised sculptors of his age, skillfully executing these giant figures in miniature. After King Francis I failed to convince Michelangelo to enter his service, artistic allusions like Cellini’s allowed him to admire and possess versions of Michelangelo’s most famous works.

One of the reclining figures separated by musical instruments from a personification of one of the four winds shown with puffed out cheeks. Benvenuto Cellini, Salt cellar, 1540-43, gold, enamel, ebony, and ivory, 28.5 x 21.5 x 26.3 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Personifications of the four winds adorn the salt cellar’s base, depicted as heads and shoulders, with puffed out cheeks, as if blowing. These are bordered by agricultural and musical instruments, representing the man-made world in miniature. The artist also found ways to imply that this harmony of Land, Sea, times of day (Night, Day, Twilight and Dawn), and winds, as well as human life, ultimately stems from the king’s power. Cellini stamped the base with golden Fs for Francis, fleur-de-lis (used in French royal heraldry), and a salamander (one of the king’s personal emblems) next to the temple.

Roman triumphal arch within temple and salamander circled in white. Benvenuto Cellini, Salt cellar, 1540-43, gold, enamel, ebony, and ivory, 28.5 x 21.5 x 26.3 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The temple also evokes the presence of a divine force (equally applicable to the king, in this new context, or to God), which would have been appropriate to its original patron, the cardinal. By creating a microcosm (a world in miniature), Cellini alludes to the king’s dominion over both the natural and man-made world, which was common in courtly art. A work like the salt cellar offered a flattering mirror to powerful patrons.

Significance for France

Benvenuto Cellini, The Nymph of Fontainebleau, 1540–45, bronze, 2.05 × 4.09 m (The Louvre; photo: Sailko, CC BY 3.0)

The complex imagery of the salt cellar would have appealed to the French king and his court for several reasons. The king and his court had particular taste for complex ornament and allegory, as well as sexual imagery—exemplified by the frescoes that adorned the king’s favorite palace at Fontainebleau. The miniature nude on top of the temple in the salt cellar resembles Cellini’s bronze Nymph of Fontainebleau, also created for King Francis I.

There was also particular reason to celebrate salt in France, where it was a prized and abundant natural resource—its tax was the largest source of royal revenue.

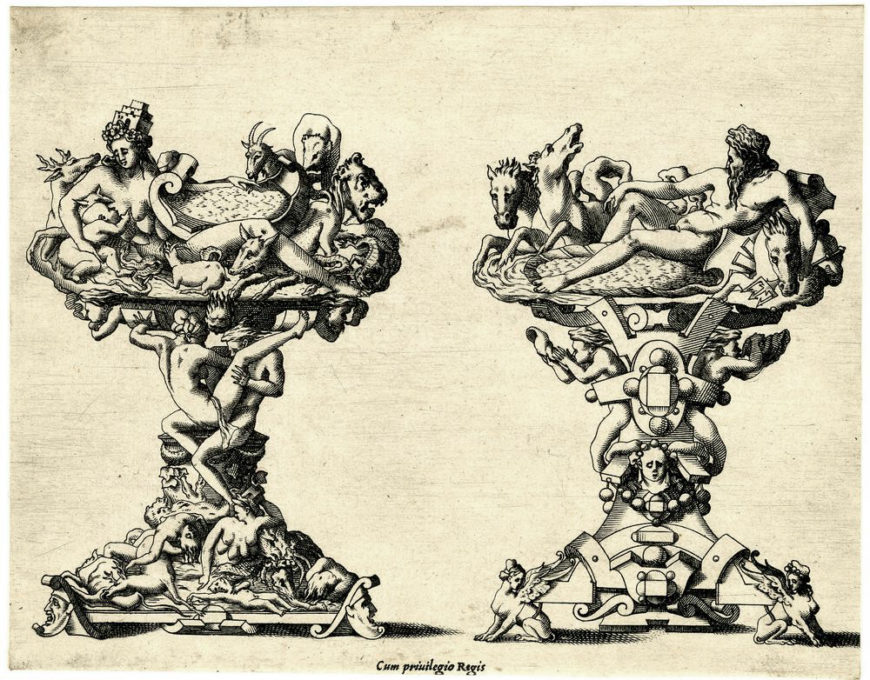

Attributed to René Boyvin, after design by Léonard Thiry, Two Designs for Salt Cellars, c.1550–60, engraving on paper, 13.2 × 16.9 cm (The British Museum)

Designs for objects similar to Cellini’s salt cellar survive from renaissance France, including one by Léonard Thiry, which places figures of Nature and Neptune on top of separate vessels for pepper and salt. Cellini was clearly borrowing symbols and allusions that had important meanings for sixteenth-century renaissance elite viewers.

Ultimately it remains unclear whether Cellini’s salt cellar was ever meant to be used, or just enjoyed as an ornament. By the artist’s own (often exaggerated) account, it was used at least once for a dinner party of his friends, before it took its place in the king’s collection. Placed on wheels to rotate and move the work along the table, this object was intended to form a centerpiece for the French king’s dining table, and the conversations of the surrounding courtiers. Its multiple levels of allusions, spanning ancient mythology, natural philosophy, and contemporaneous art, undoubtedly created rich and open discussions and showcased the artist’s own wit.

Seahorses (detail), Benvenuto Cellini, Salt cellar, 1540-43, gold, enamel, ebony, and ivory, 28.5 x 21.5 x 26.3 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

A work to be remembered

Cellini’s lengthy descriptions make it clear that he wanted this work to be remembered, even if the salt cellar were somehow lost or destroyed. His fears were indeed justified, as the salt cellar’s history is full of narrow escapes. It is his only work in precious metal that can still be seen today; few statues made from precious metals survive, as they were often melted down for their materials. By Cellini’s own account, he even defeated armed bandits, who attempted to steal the gold before work even began. Despite his record, Cellini’s authorship was almost immediately forgotten until the eighteenth century.

Benvenuto Cellini, Salt cellar, 1540-43, gold, enamel, ebony, and ivory, 28.5 x 21.5 x 26.3 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

By the time it was stolen in 2003, although the artist himself could no longer guard this covetable work, its own fame had cast a protective spell. Finding out that he had in fact stolen Cellini’s famed masterwork, one of the most prized objects in the Kunsthistoriches Museum, the thief buried this treasure in a nearby forest, and turned himself in to the police.