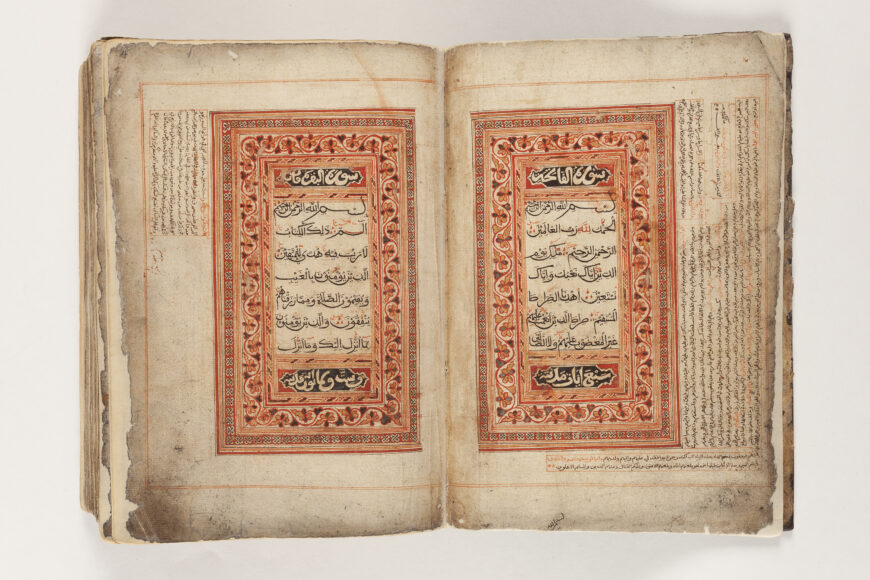

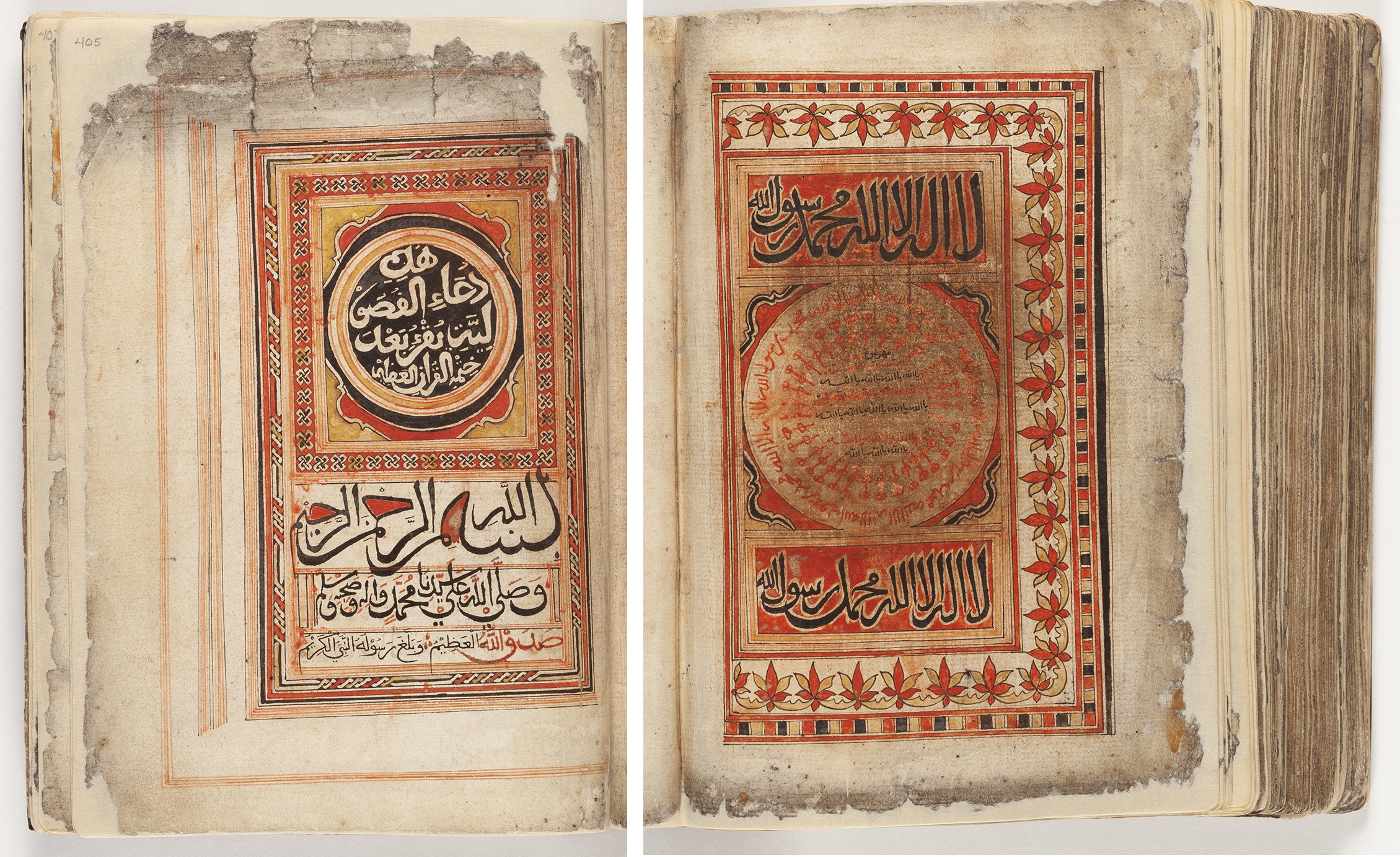

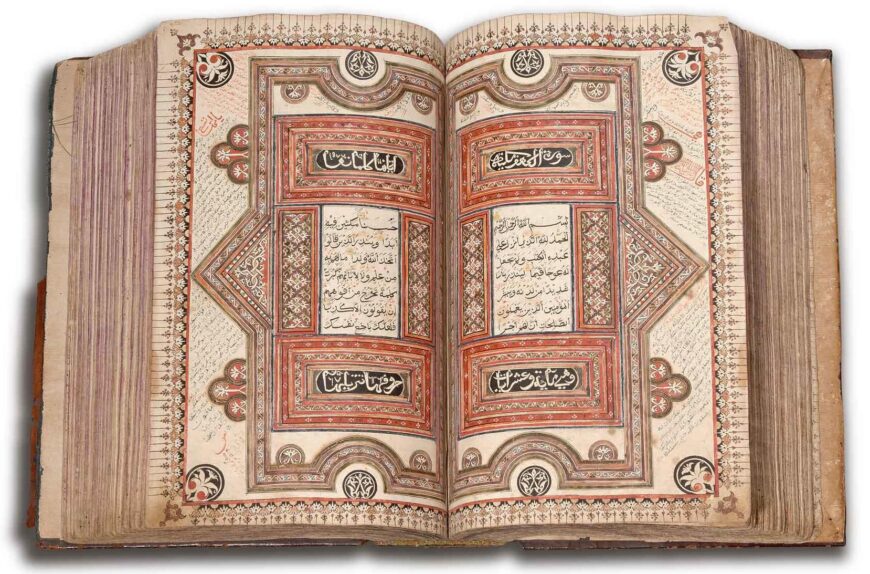

Unidentified artist, Qur’an, frontispiece, between the second half of the 18th century and first half of the 19th century (Swahili people, Siyu, Kenya), North Italian paper, ink, leather binding, 26.5 x 20.3 x 7.6 cm (Fowler Museum at UCLA, X90.184A, B. Gift of the The Jerome L. Joss Collection; image © Fowler Museum at UCLA, photo: Don Cole, 2019)

The Qur’an manuscript in the Fowler Museum in Los Angeles is a rare example of illuminated Qur’an produced in coastal East Africa on Pate Island made between the second half of the 18th century and first half of the 19th century. It is the only known example of a complete, single-volume Qur’an from the region. [1] Its materials, calligraphy, and decorations tell us many stories about the Muslims in this region of Africa: how they expressed their faith, their traditions of religious teaching and learning, their aesthetic inclinations and artistic production, and their connections to other parts of the world.

Muslims consider the Qur’an to be Divine Revelation conveyed by God (Allah) to the Prophet Muhammad through the Archangel Gabriel in exquisite Arabic. The Qur’an is believed to be God’s final message to humankind and the verbatim Word of God. Hence, each utterance and written form of the Qur’an’s letters and words is considered sacred. Ever since the Prophet’s time, Muslims have safeguarded God’s Word and highlighted its sacred character through rich and diverse traditions of recitation, inscription, translation, and interpretation. Inscribing the Qur’an using beautiful calligraphy on surfaces such as stone, parchment, and paper developed over many centuries.

A Qur’an manuscript from East Africa

Muslims from different regions developed many styles of Qur’an manuscripts, including Qur’ans with elaborate decoration.

Coastal East Africa, also known as the Swahili Coast, stretches from southern Somalia to northern Mozambique and includes islands such as Zanzibar, the Comoros, and Madagascar. It has been home to a diversity of Muslim communities since the 8th century C.E. Its peoples have also had centuries-long interactions through trade and migration with Muslim communities from other parts of Eastern Africa, as well around the Indian Ocean from Arabia, to Iran, South Asia, and China. Despite the well-established nature of Muslim communities on the Swahili Coast, manuscripts of the Qur’an are remarkably rare. Only a small corpus of twelve illuminated Qur’an manuscripts from the Swahili coast survives, including the one in the Fowler Museum in Los Angeles. [2] These were produced between about 1750 and 1850 in modern-day Kenya, specifically in the historical Muslim city-states of Pate, Siyu, and Faza on Pate Island in the Lamu Archipelago. The manuscripts are notable for their scripts and distinctive style of illuminations, as well as their use of paper that was likely produced in northern Italy.

But why have so few Qur’ans from the region come to light? So far scholars have no convincing explanation for this. Some suggest that the region’s humidity and salty ocean air may have contributed to the rapid decay of manuscripts (which are typically made of fragile organic materials such as parchment, paper, cloth, and leather). Another factor may be that art historians and other scholars have paid limited attention to the region’s written traditions, particularly in Arabic, the language of the Qur’an. This may be particularly true of Islamic art historians who have often regarded the art and material culture produced in African contexts as less important than the art produced in other parts of the Islamic world. It is also worth noting that much of coastal East Africa has seen regular and sustained political upheaval owing to local power struggles as well as conquest and occupation on the part of European and Omani powers. Such turmoil may also have contributed to the destruction or dispersal of portable items such as manuscripts to other parts of the world.

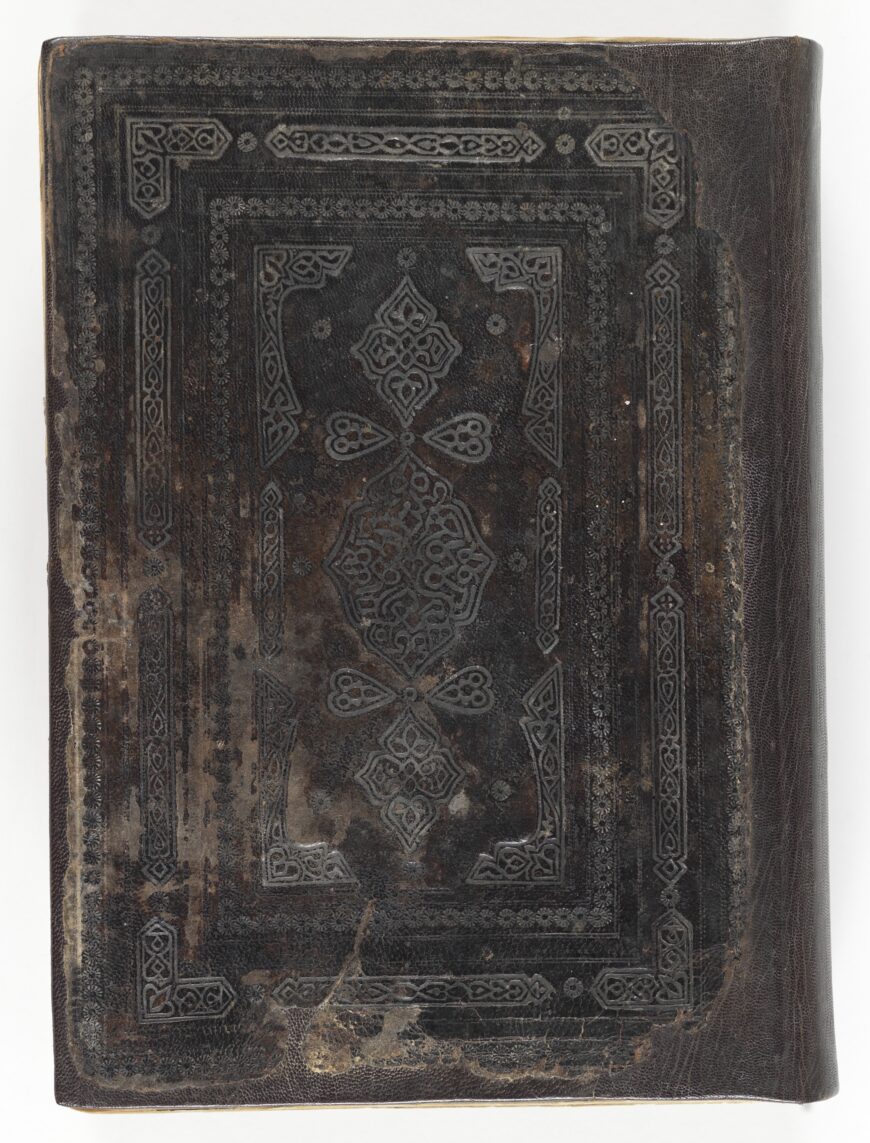

Unidentified artist, Qur’an cover, between the second half of the 18th century and first half of the 19th century (Swahili people, Siyu, Kenya), 26.5 x 20.3 x 7.6 cm (Fowler Museum at UCLA, X90.184A, B. Gift of the The Jerome L. Joss Collection; image © Fowler Museum at UCLA, photo: Don Cole, 2019)

A Qur’an manuscript from the Lamu Archipelago in Los Angeles

The Fowler Museum illuminated Qur’an is bound in a dark brown leather cover with raised floral and foliate designs that were made by impressing with metal stamps or dies.

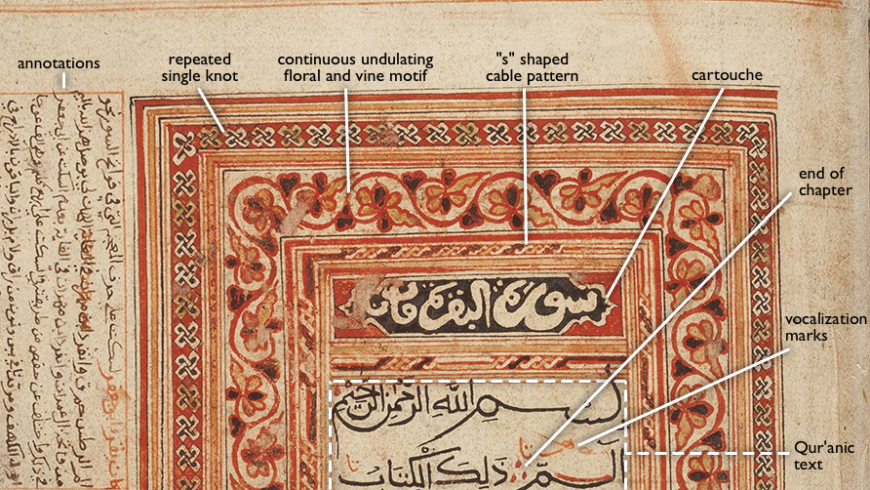

Annotated frontispiece (detail), unidentified artist, Qur’an, between the second half of the 18th century and first half of the 19th century (Swahili people, Siyu, Kenya), North Italian paper, ink, leather binding, 26.5 x 20.3 x 7.6 cm (Fowler Museum at UCLA, X90.184A, B. Gift of the The Jerome L. Joss Collection; image © Fowler Museum at UCLA, photo: Don Cole, 2019)

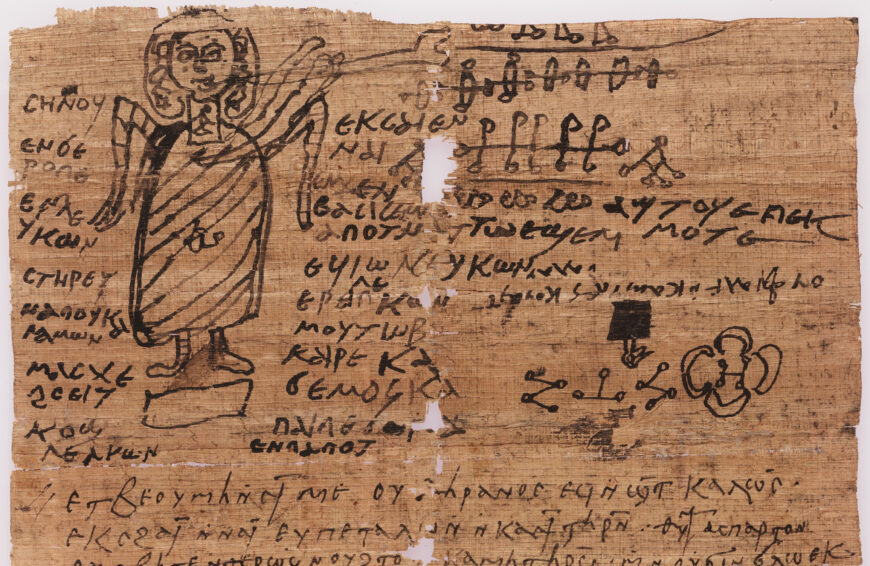

In the illuminated two-page frontispiece that opens the manuscript, multiple decorative rectilinear frames surround the Qur’anic text with motifs in red, yellow-brown, and black. Starting from the outermost frame, there is: 1) a repeated single knot; 2) a continuous undulating floral and vine motif; and 3) an “s”–shaped cable pattern.

On each page, curvilinear cartouches located above and below the Qur’anic text contain chapter titles (in this case sura al-fatiha (1) and sura al-baqara (2)), the places where God revealed the verses to the Prophet Muhammad—Mecca or Medina, and the number of verses. The text of these titles is rendered in white reserved on a black ground. Their script style is cursive with some letters stacked above others and other letters overlapping.

The Qur’anic text (all letters and vowels) occupies the central panels of the pages and is written in black ink with the exception of the word Allah (God) which is written, or rubricated, in red. Red ink is also used for vocalization marks and the three dots in a triangular shape that indicate the end of each verse. The Qur’anic script is cursive, meaning that the letters are joined up rather than written out separately. It resembles a fairly common style of Arabic calligraphy used widely by scribes since the early period of Islam called naskh but has some distinctive features, especially the tails of some letters which swoop under others. At present, it appears that the script style used in this Qur’an was locally developed as almost no other comparable examples exist outside the region.

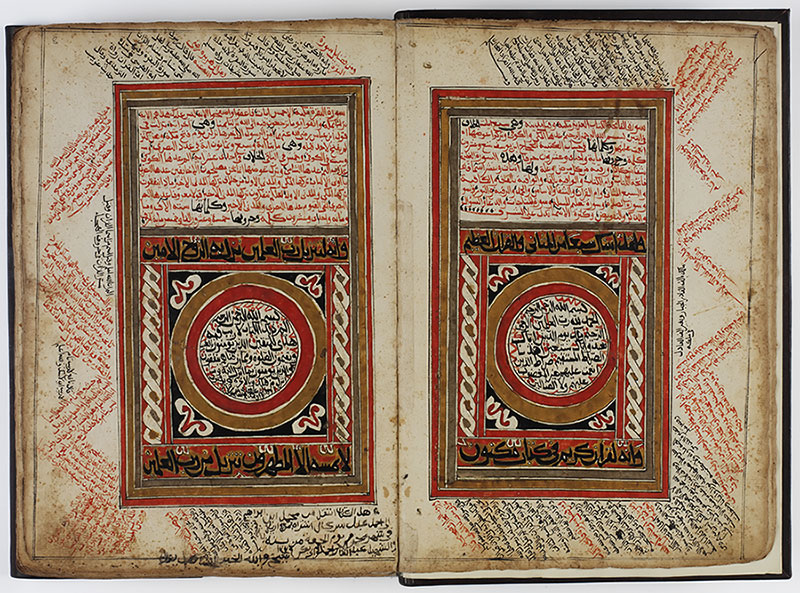

In the margins, outside the decorative frames, are annotations placed in rectangular boxes. These contain information concerning the standard variant readings or recitations of the verses as well as commentary about the verses written by authoritative Islamic scholars. The cursive script of the annotations is written in black and red inks. While smaller than the Qur’anic text, the calligrapher’s hand displays similar characteristics—suggesting the possibility that the same person was responsible for copying out the manuscript and annotating it.

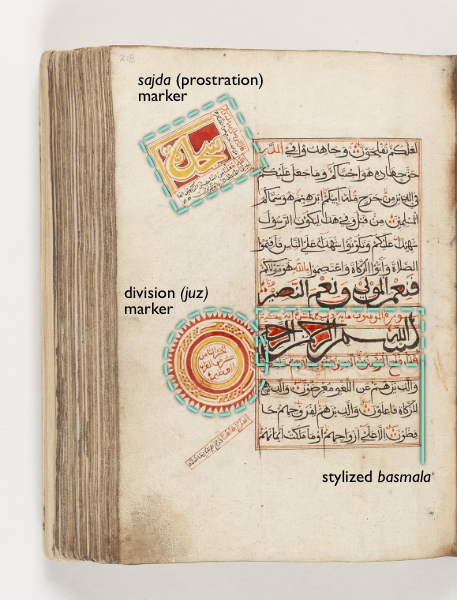

Unidentified artist, Qur’an, between the second half of the 18th century and first half of the 19th century (Swahili people, Siyu, Kenya), North Italian paper, ink, leather binding, 26.5 x 20.3 x 7.6 cm (Fowler Museum at UCLA, X90.184A, B., folio 218 recto, Gift of the The Jerome L. Joss Collection; image © Fowler Museum at UCLA, photo: Don Cole, 2019)

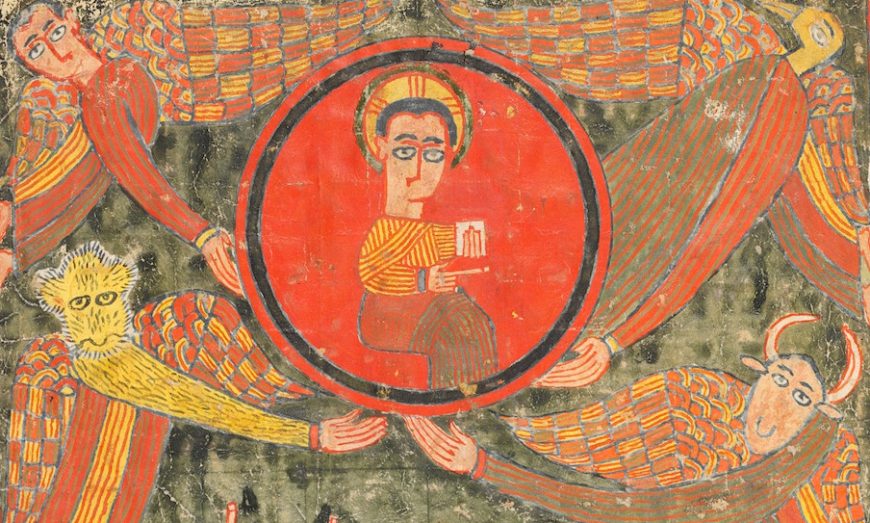

Other pages in the manuscript contain many different decorative features and stylized text. These include: decorated prostration (sajda) markers that indicate to the reader where to bow in prostration when they are reading the Qur’an; a division (juz) marker that is used to divide the Qur’an into parts or sections to ease memorization or reading, chapter titles; and, highly stylized basmalas, the Arabic incipit “in the name of God the Most Beneficent the Most Merciful” (“bismillāh al-raḥmān al-raḥīm”).

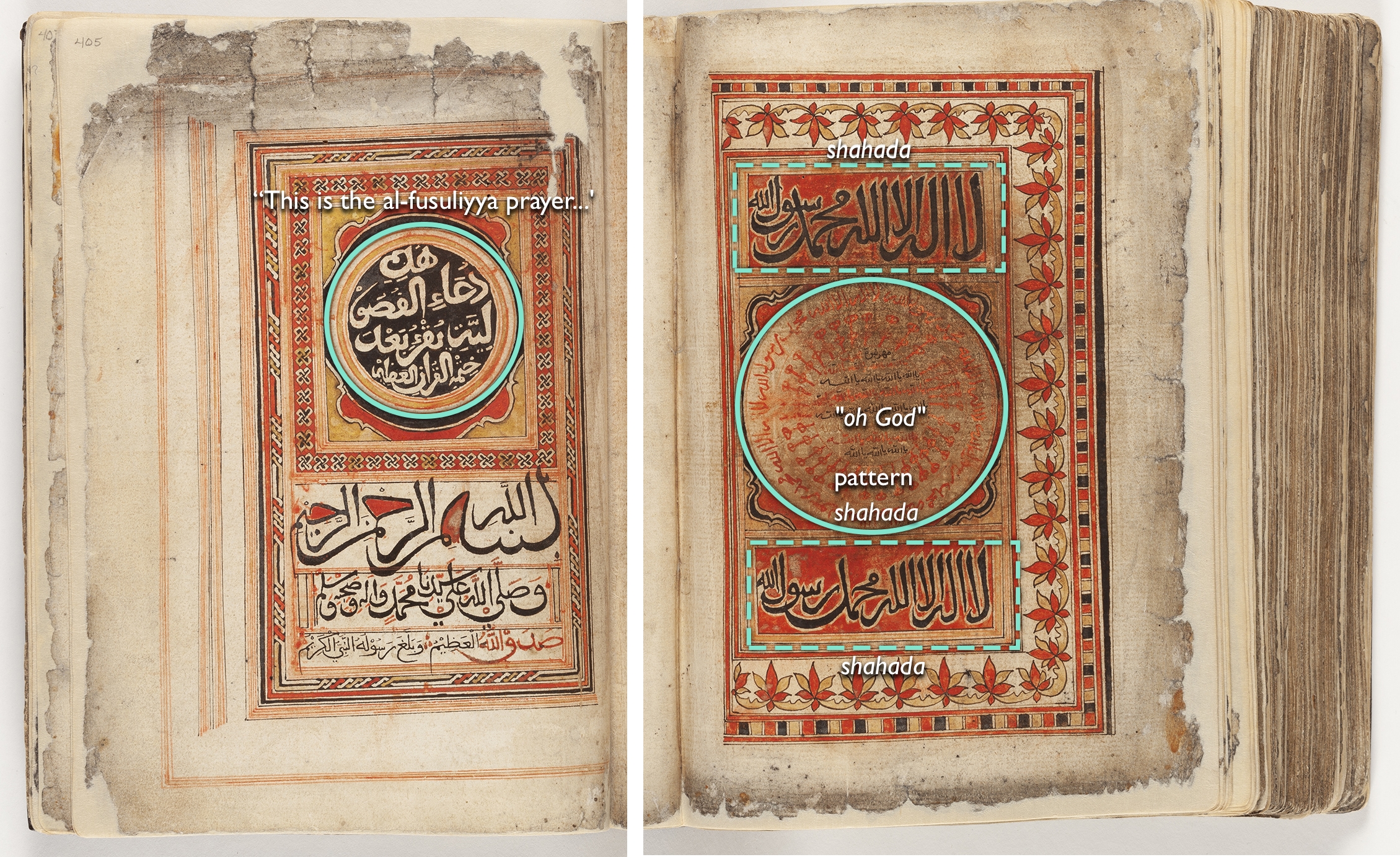

Pages showing supplication sections with decorative and inscribed roundels. Unidentified artist, Qur’an, frontispiece, between the second half of the 18th century and first half of the 19th century (Swahili people, Siyu, Kenya), North Italian paper, ink, leather binding, 26.5 x 20.3 x 7.6 cm (Fowler Museum at UCLA, X90.184A, B., folios 405 recto and 413 verso, Gift of the The Jerome L. Joss Collection; image © Fowler Museum at UCLA, photo: Don Cole, 2019)

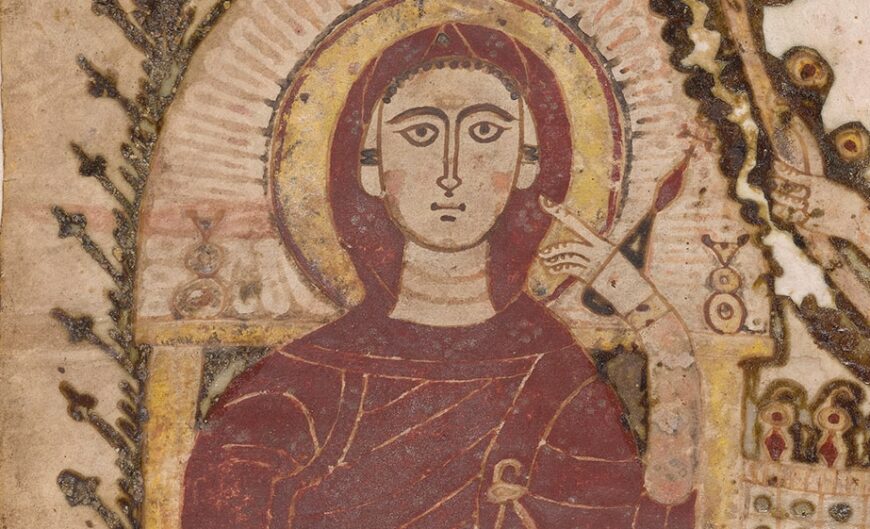

After the end of the Qur’anic text, the manuscript has two sections with decorations that contain supplicatory prayers meant to be read after completing the reading of the Qur’an. The beginning of the first prayer is marked with a roundel framed within several patterned bands (image above, left). Rendered in reserved white lettering against a black ground, the Arabic text in the roundel reads: “This is the al-fusuliyya prayer to be read after completing the reading of the Magnificent Qur’an” (“hādhā du’ā al-fusūliyya yuqra’ ba’da khitmat al-Qur’ān al-azīm”). The beginning of the second supplicatory section is marked by a roundel with calligraphic panels above and below. (image above, right) These panels include the Arabic text of the Muslim proclamation of faith (shahada): “There is no God but God, Muhammad is the Messenger of God.” Composed of three concentric sections, the roundel’s innermost section contains the invocation “Oh God” (“Ya Allāh”) written in red, black, and brown inks. The middle section is inscribed with a continuous pattern in red. The outermost section has the shahada inscribed around the circle in red, running counter-clockwise.

A patron, place, and date of production

The manuscript contains no date. [3] However, based on the paper’s ribbed texture, made by a paper mold, and watermarks detected on some of the sheets, it is likely that the manuscript’s paper was produced in northern Italy sometime after around 1750 C.E. Such paper was shipped from Europe to Africa through Egypt and Sudan in the 18th and 19th centuries, but it is not known how and when this paper made its way from north-eastern Africa to the Lamu Archipelago.

The time period in which the manuscript was produced, c. 1750–1850, is regarded by scholars as an era of cultural efflorescence on the Swahili Coast. Pate, the Island’s largest city-state, was ruled by the Nabahani dynasty who oversaw the growth of independent maritime trade between coastal East Africa and the Indian Ocean coast, particularly Gujarat. Ivory and textiles were some of the prized commodities that transited through Pate’s harbor alongside migrants and travelers from various parts of Africa and the Western Indian Ocean. Up to now, there is very limited historical evidence of the transit of enslaved people through the port. In 1800, Pate Island’s main city-states of Pate, Siyu, and Faza had a combined population of some forty-thousand people and boasted urban settlements comprised of stone houses, districts, and numerous mosques. The island’s population was diverse, comprising of Muslims and non-Muslims of different ethnic backgrounds, Indigenous groups, mainland migrants as well as people from other parts of the Swahili Coast, Eastern Africa, and the Western Indian Ocean littoral including Arabia and India.

A distinct Pate Island style

The decorative features of the illuminated Qur’an manuscripts produced on Pate Island share many features with other types of material culture from the Swahili coast. For example, patterns and motifs on the manuscripts’ frontispieces closely correspond to those found on the stucco decorations of wall niches and wooden-carved door surrounds of the coast’s 18th- and 19th-century houses.

Swahili artist, Tombstone, 1462 (Kilindini, Mombasa County, Kenya), Coral rag (limestone) (Mombasa Fort Jesus Museum, National Museums of Kenya)

The same knot motif found on the Qur’an frontispieces also appear on objects such as a tombstone from Kenya dating to the 15th century. Such tombstones also contain inscriptions with stacked and overlapping letters similar to the script used in some of the Qur’ans’ chapter titles. These and many other examples suggest that the manuscripts’ copyists were working with other local artists and sharing or borrowing from each other. This also suggests that the copyists were working within an established aesthetic tradition that utilized a series of known motifs and patterns that suited local tastes and that manuscript producers were creating a distinctive local style by using local motifs and patterns well-known in other media.

Opening pages, Qur’ān manuscript, completed on šawwāl 1162/September or October 1749 (Harar, Ethiopia), copied by ḥāğğ Sa‘d ibn Adish Umar Din (Khalili Collection, London)

Bihari Qur’an, c. 1400–1525 (Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.)

Eastern African and other Indian Ocean resonances

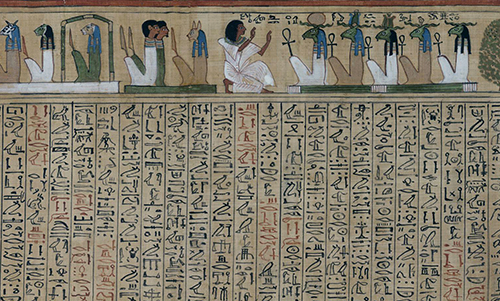

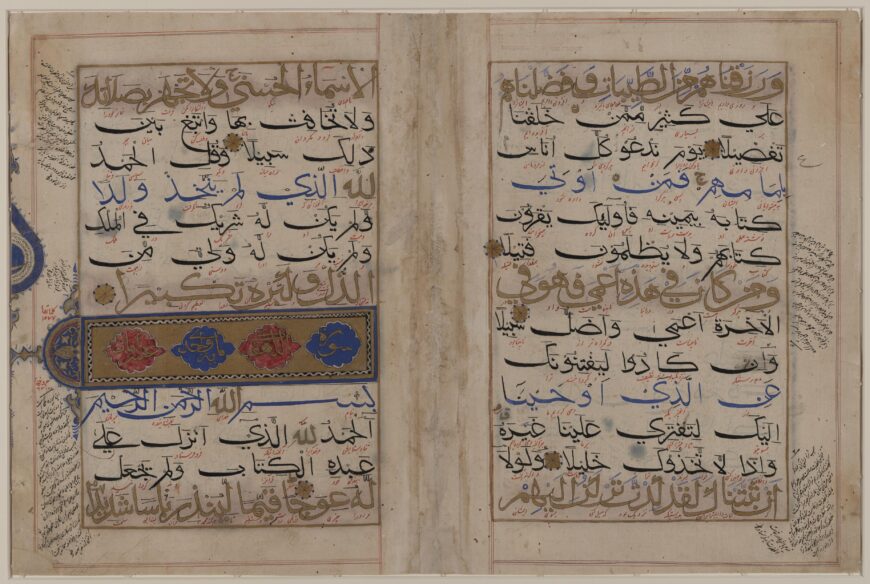

There are also correspondences between Pate Island’s corpus and Qur’an manuscripts produced in other parts of the Indian Ocean littoral. For example, Qur’ans from Harar, Ethiopia use inks in colors similar to those produced on Pate Island, while Indian Qur’ans of the 14th and 15th centuries are copied in a bihari script that has comparable letter forms and the word Allah rendered in red or gold.

Boné Qur’an, copied by: Ismail b. `Abdullah of Makassar, 1804 (Indonesia), ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper (Aga Khan Museum, Toronto, AKM488)

Qur’an manuscripts from the Malay Archipelago in Southeast Asia also show resemblances. For example, the Boné Qur’an from South Sulawesi, Indonesia, has chapter titles with white lettering against a black background contained within curvilinear cartouches. The Boné Qur’an manuscript’s opening pages also contain a frontispiece with a series of layered and decorated rectilinear frames. Despite such similarities, however, these various manuscript traditions appear to be distinct, and the histories of how these traditions came to share some stylistic feature remains to be understood.

View of zidaka (wall niches) in ndani (harem) in the McCrindle House in Lamu, Kenya, from the collection James de Vere Allen: Swahili Kingdoms (MIT Library, Boston)

The place of the Qur’an in the life of historical Swahili communities

The text of the Qur’an appears to have been central to the life of the historical Swahili Muslim communities of Coastal East Africa. Qur’anic ideas were incorporated into Swahili-language poetic texts and Qur’anic verses were inscribed on the prayer niches (mihrabs) of mosques.

The illuminated Qur’an manuscripts of Pate Island were probably used for worship or study in local mosques. The effort taken by copyists to mark vowels, highlight particular phrases, and provide commentary on readings suggests that they were concerned that Qur’anic text be properly recited. In addition to mosques, Qur’ans may also have been stored inside the homes of local patrons, particularly in elaborately stucco-decorated wall niches known as vidaka/zidaka that were also used for storing and displaying other precious and luxury items such as imported ceramics and glass.