Essay by Yu Heisun

Dagger and gold scabbard, 6th century, dagger: iron, scabbard: gold alloy, garnet, and glass, 36.8 x 9.05 cm, Gyerim-ro Tomb 14, Gyeongju, Treasure 635 (Gyeongju National Museum)

In 1973, during maintenance around the Tomb of King Michu, grave goods of the highest quality were found inside Gyerim-ro Tomb 14 in Gyeongju. This was quite a surprising find, since Gyerim-ro Tomb 14 was not a particularly large tomb. One item that aroused particular interest was a dagger and gold scabbard (Treasure 635), the latter of which was decorated with inlaid jewels and attached gold granules. Based on its distinctive shape and production technology, which have never been seen in other Silla artifacts, the scabbard is believed to have been produced in the sixth century in Iran or Central Asia.

The scabbard appeared to be decorated with red agate, along with an unknown bluish-gray stone, but the jewels could not be conclusively identified with the naked eye. Thus, through non-destructive methods (such as X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy), a scientific analysis was conducted in order to determine the composition of the inlaid stones and granules on the scabbard.

Dagger, 6th century, iron, 36.8 x 9.05 cm, Gyerim-ro Tomb 14, Gyeongju, Treasure 635 (Gyeongju National Museum)

Which materials were inlaid into the gold scabbard?

To identify and analyze the materials that had been inlaid into the gold scabbard, an array of different techniques were applied, including X-ray diffraction (XRD), ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometry (UV-VIS), and scanning electron microscopy accompanied by an energy dispersive spectrometer (SEM/EDS).

SEM/EDS can be used to analyze light elements (e.g., Na, K, Mg, O) and to analyze the composition of nonmetallic oxides; it can also be effective for analyzing very small areas, such as the place where the gold granules were attached. However, SEM/EDS alone cannot confirm whether a sample is glass or a mineral. Thus, XRD analysis, which utilizes the physical phenomenon of X-ray diffraction, was also employed. Since glass is a non-crystalline solid, it does not diffract X-rays, which allows XRD analysis to distinguish between glass and minerals. Finally, UV-VIS can be used to precisely identify minerals, since different minerals generate different colors (i.e., different wavelengths) in the visible and ultraviolet spectrum.

Detail of gold scabbard, 6th century, gold alloy, garnet, and glass, 36.8 x 9.05 cm, Gyerim-ro Tomb 14, Gyeongju, Treasure 635 (Gyeongju National Museum)

Using these techniques, it was determined that the scabbard was inlaid with both glass and garnet. To be specific, the larger oval stones are glass, while the smaller “yin-yang” and leaf-shaped pieces are garnet stones. Among the various types of garnets, rhodolite was primarily used, along with some hessonite. Rhodolite stones exceeding three carats are quite rare, and thus would have been regarded as highly precious jewels. Therefore, it is likely that rhodolite stones of around two carats were used to make the “yin-yang” pieces used to decorate the scabbard.

Although there are many possible sources for the garnets, the production of this precious jewel is extremely limited. Thus, information about the source of the garnets could be crucial for helping us understand where the dagger and scabbard were produced and how they made their way to Silla. Hopefully, through present and future analyses, we will soon be able to conclusively identify the source of the garnets used in the scabbard.

Detail of gold scabbard, 6th century, gold alloy, garnet, and glass, 36.8 x 9.05 cm, Gyerim-ro Tomb 14, Gyeongju, Treasure 635 (Gyeongju National Museum)

Analysis of the gold granules

In addition to the precious stones, the scabbard was also lavishly adorned with gold filigree techniques, in which gold wire and granules were delicately attached to the metallic surface. These methods required both precision, for the production of gold wire and granules, and highly advanced technology, for soldering the thin wires and granules onto the metallic surface.

To attach gold granules to metal, lead soldering is often used, in which the space between the granule and the surface is filled with molten lead. As variations on this technique, cuprous salt is sometimes added to the solder, or in some cases, gold is used as the solder.

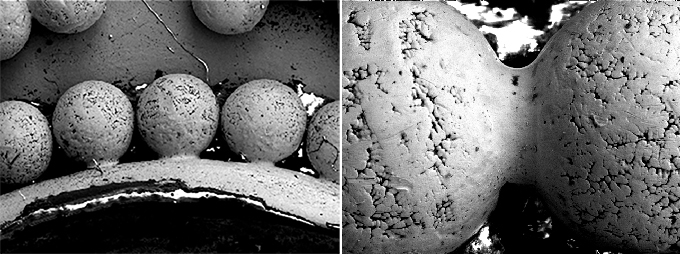

Left: X-ray photograph of the gold granules; right: detail of gold granules on gold scabbard, 6th century, gold alloy, garnet, and glass, 36.8 x 9.05 cm, Gyerim-ro Tomb 14, Gyeongju, Treasure 635 (Gyeongju National Museum)

The gold granules on the scabbard are extremely uniform in both size and shape, and can be classified into three sizes—large, medium, and small—with respective diameters of approximately 240μm (0.24 mm), 150μm (0.15 mm), and 130μm (0.13 mm). It was expected that some of the large granules might show some deviation in size, but amazingly, the variation was never greater than 2μm (0.002 mm).

XRF analysis was used to determine the composition of the gold plate, wire, and granules. The average composition of the gold plate was found to be:

- gold (Au) 78.8wt%;

- silver (Ag) 17.6wt%; and

- copper (Cu) 3.3wt%.

The average composition of the gold wire was Au 79.5wt%; Ag 17.4wt%; and Cu 3.0wt%. Finally, the composition of the gold granules was Au 77.0wt%; Ag 18.0wt%; and Cu 4.0wt%. To summarize, the gold plate, wire, and granules were alloys consisting of similar proportions of gold, silver, and copper.

SEM image (left) and magnified SEM image (right) showing branch-like cracks on the surface of the gold granules. Gold scabbard, 6th century, gold alloy, garnet, and glass, 36.8 x 9.05 cm, Gyerim-ro Tomb 14, Gyeongju, Treasure 635 (Gyeongju National Museum)

Pure gold has a melting point of 1064°C, but the melting point of the alloys used to make the gold scabbard was considerably lower, at approximately 980°C. Thus, the gold wire and granules could be attached directly to the surface with a momentary application of heat, without the use of an additional mediator such as gold solder. Indeed, no solder is visible in SEM images of the scabbard, indicating that fusion welding had been used instead. The SEM images also reveal some branch-like cracks on the surface of the granules, which is a feature of metal alloys that is not observed with pure metals.

Left: gold earrings from Bubuchong Tomb, mid-6th century (Silla Period), Bomun-dong, Gyeongju, National Treasure 90 (National Museum of Korea); right: gold earrings, 5th–6th century (Silla Period), 9 cm long, 3.6 cm diameter, Treasure 557 (Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art)

Gold filigree techniques of ancient Korea

Analysis of filigree techniques on other fine metalwork artifacts from the Korean peninsula has revealed that most were soldered with a gold-silver alloy as the solder. For example, this technique was used to make the thick-ring earrings from the Double Burial in Bomun-dong; the thin- and thick-ring earrings from the collection of Hoam Museum; and the gold bell from the East Three-Story Pagoda of Gameun-sa Temple, which dates to the Unified Silla Period.

Dagger and gold scabbard, 6th century, dagger: iron, scabbard: gold alloy, garnet, and glass, 36.8 x 9.05 cm, Gyerim-ro Tomb 14, Gyeongju, Treasure 635 (Gyeongju National Museum)

Notably, the filigree techniques used to create this gold scabbard have never been seen with any other ancient Korean artifacts. Hence, the scabbard was probably produced in another country, although the exact location of its production has yet to be determined. The hope is that, by continuing to analyze a wider range of artifacts decorated with filigree techniques, we may eventually accumulate enough data to specify the scabbard’s place of manufacture.