By Elisabeth Yota

During the Byzantine Empire book production occurred on a large scale, especially after the end of Iconoclasm in 834. Although illuminated manuscripts only represent about 5% of this production, they are of great interest for the study of Byzantine manuscripts because of the amount of information they can give us about both palaeography and art history. Study of the colophons and notes of the manuscripts indicates intense activity at the capital of the Empire, Constantinople, owing to the presence there of imperial scriptoria (workshops) as well as the great monasteries (such as the Monastery of Stoudios, the Hodegon, etc). However, centres in the provinces of the Empire (Thessaloniki, Cyprus, Palestine, Asia Minor, Mount Athos, etc) show equally important production.

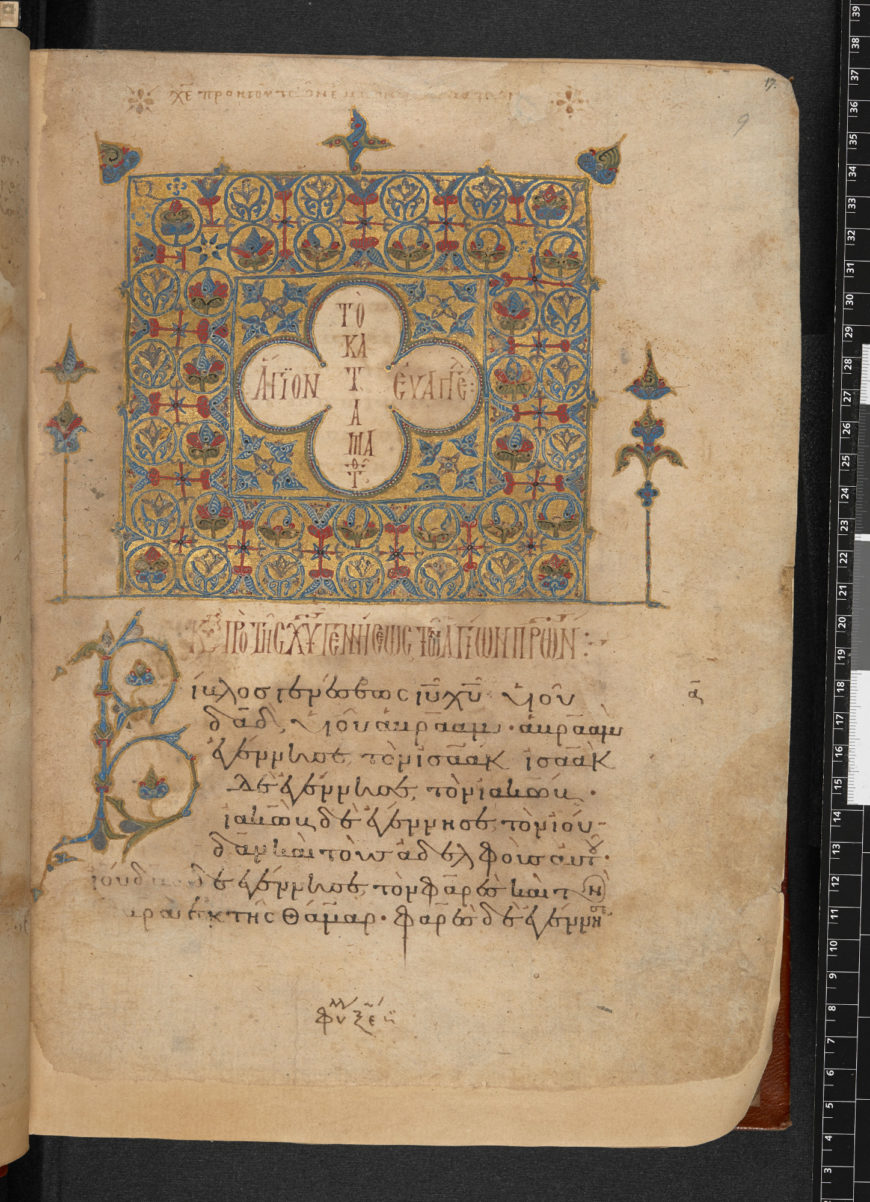

Not far from the capital of the Empire, Thessaloniki was a prominent centre of intellectual activity, especially during the Palaeologan era. We cannot say with certainty whether one or more scriptoria existed in this city, but we do know that several copyists lived and worked there. For example, Theodore Hagiopetrites, scribe and miniaturist, was active in the city between 1277/78 and 1307/08. He specialised in copying religious books, especially biblical manuscripts. Hagiopetrites not only copied the text, he also produced the ornamental illustrations in his manuscripts. The British Library maintains one of the best examples of his art, such as Burney 21, dated to 1292, which was made for the monk Gerasimos, grand sceuophylax of the monastery of Philokalos in Thessaloniki.

Decorated headpiece with foliate patterns in gold and colours at the beginning of the Gospel of Matthew (Burney MS 21), Illuminated Gospels from Thessaloniki. Learn more about this object.

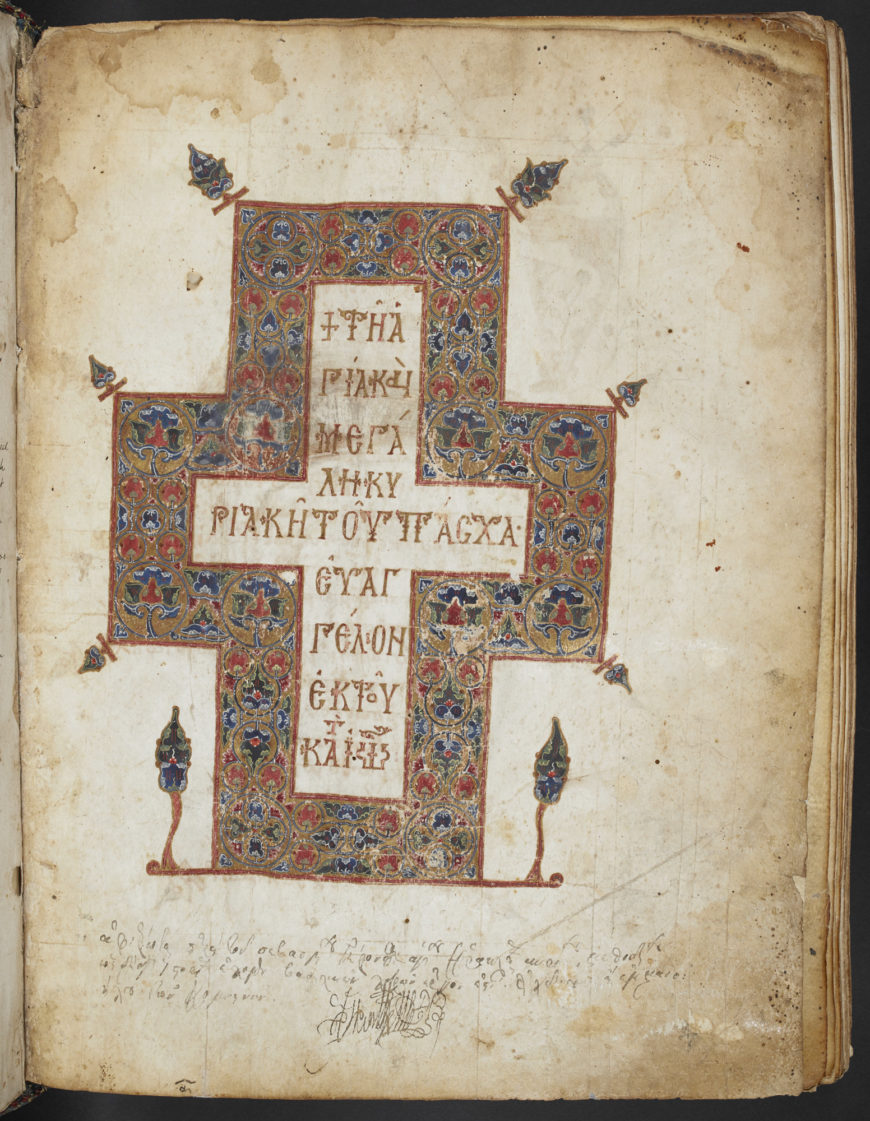

The British Library now holds a number of manuscripts formerly preserved in the monasteries of Mount Athos, located on the peninsula of Halkidiki, east of the city of Thessaloniki. In 1837, Robert Curzon visited the monasteries and negotiated the purchase of several manuscripts. In addition to a large number acquired at the Karakallou Monastery (Additional 39593, 39594, 39599, 39601, 39602, 39606, 39607, 39608, 39609, 39612, 39617, 39623), Curzon bought a large 12th-century illuminated lectionary (Additional 39603) at the Pantocrator Monastery. In this manuscript, the text is written in the shape of a cross. The beginning of each section is surrounded by large ornamental borders, while on every page the text is accompanied by finial ornaments and decorated initials.

The text in this manuscript is written in the shape of a cross, an elaborate border on the first page of each section (Add MS 39603), Curzon Cruciform Lectionary. Learn more about this item

The fact that these manuscripts were discovered and acquired on Mount Athos does not prove that they were created there, nor is it evidence for the existence of one or more scriptoria in the monasteries. Many monasteries on Athos had metochia (annexes) elsewhere in the Byzantine Empire, including places like Thessaloniki, Cyprus and Palestine. This supports the hypothesis that many Athonite manuscripts were made elsewhere and only later arrived on the mountain. This would suggest, first, that it was possible to commission a manuscript at some distance, and second, that when the monks travelled from one monastery to another, they would use manuscripts, especially illuminated ones, as gifts.

The island of Cyprus, a prosperous province and place of much cultural interaction, was an important centre of book production. Thanks to its strategic location and to the rise of the great monastic institutions that facilitated and promoted the copying of texts, Cypriot written culture shows uninterrupted development from the 11th–16th centuries. The manuscripts from this context display elements distinct to Cyprus and neighbouring regions of the Levant in their palaeography, methods of production, decorations and illuminations. Until the mid-12th century, Cypriot Greek manuscripts reproduce styles common to other regions of the Byzantine Empire, but great innovation occurs in the second half of the 12th century and characterises Cypriot written culture until the early decades of the 13th century.

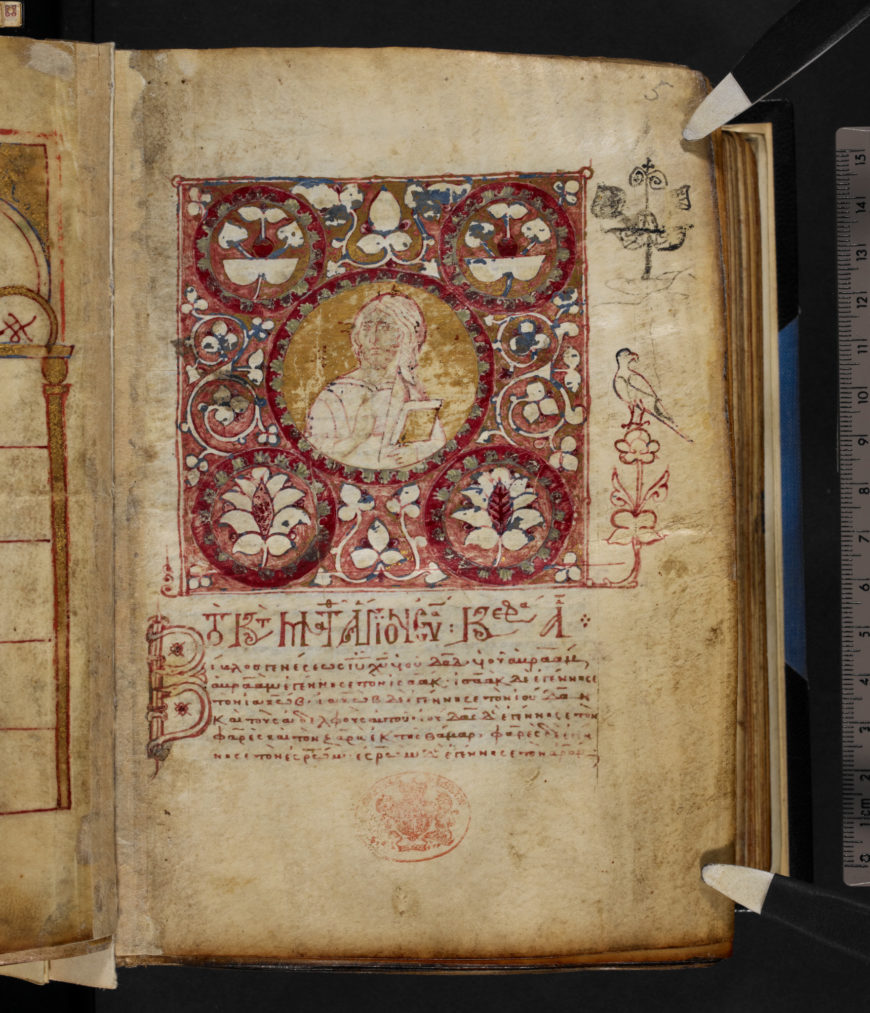

A new writing style appears at the same time on the island and in Palestine, called the ‘epsilon style’. This script, similar to conventional Greek script, is characterised by thick lines, the use of very dark black ink, regular shapes, and the large number of majuscules (capital letters) included in the text. Of certain Cypriot provenance is the New Testament and Psalter now kept in the British Library as Additional 11836. Two ownership inscriptions mention the name of St. Barnabas Church in Vassa and the copyist Makarios Porphyropoulos. The manuscript is decorated with a portrait of Christ at the beginning of the Gospel of Matthew (fol. 5r), portraits of the evangelists Luke and John (fol. 60v, 97v) and a few miniatures that illustrate the Psalms (fol. 124v, 267v, 293r , 297v, 298(r), 300r-v, 301v, v-302r, 304r).

The headpiece at the beginning of the Gospel of Matthew contains a portrait of Jesus in a medallion (Add MS 11836), Illuminated New Testament and Psalter from Cyprus. Learn more about this item

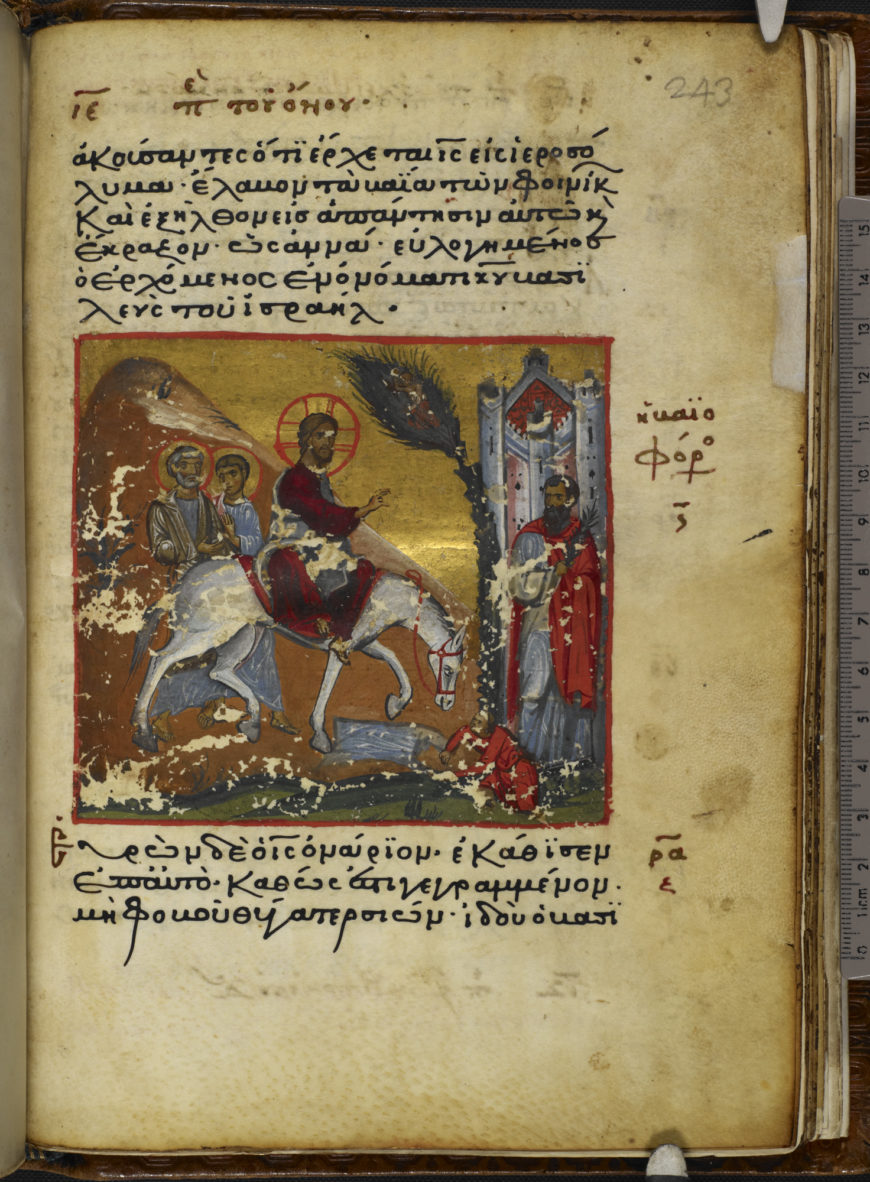

Other illuminated manuscripts of the same group, commonly called ‘decorative style’ manuscripts, very rarely provide clear indications of dating or location. Their connection to a Cypriot centre or the neighbouring area is based on palaeographic, iconographic and stylistic comparisons with manuscripts dated or located with certainty. One such example is Harley 1810, a manuscript of the Gospels dated to the late 12th century. We are given vague information on a possible location for the manuscript in a note (f. 269r) written in a 15th- or 16th-century hand. This note states that the manuscript belonged to the Monastery of the Prophet Elias, but the location of the monastery is not mentioned.

Scene depicting Christ’s entry into Jerusalem (Harley MS 1810), Harley Greek Gospels. Learn more about this item

The manuscript is decorated with 20 miniatures depicting the great liturgical feasts of Christ, canon tables, ornamental decorations at the beginning of each Gospel and four portraits of the Evangelists. Its membership in the ‘decorative style’ group is based on palaeographic (specifically its use of the ‘epsilon style’) and iconographic similarities with dated and localised manuscripts. Its creation in Cyprus or in a centre of the surrounding area raises the problem of manuscript scriptoria in the provinces of the Empire. Although textual sources and colophons confirm the existence and operation of scriptoria for some major monasteries in Constantinople, this is not the case for provincial centres such as Cyprus.

Given the remarkable geographical range of ‘epsilon style’ manuscripts, it must be assumed that production was divided among various centres where itinerant scribes and illuminators temporarily came together to complete a specific project, and somehow imposed their scribal and iconographic standards. In addition, the presence on the island of metochia of the Orthodox monasteries of Jerusalem, and the close relationships maintained by Cyprus with other regions, contributed to the wide dissemination of Cypriot written culture through the exchange of scribes and books. This is the case for many manuscripts that Robert Curzon bought on his trips to the monasteries of Jerusalem, particularly the monastery of St. Sabas (Additional 39604, 39585, 39586, 39587, 39588, 39590, 39595, 39596, 39597, 39598). Other examples are a 13th-century psalter (Additional 11835) which belonged to Gregory of Cyprus, priest-monk at the Monastery of St Catherine on Mount Sinai, or a 12th-century menologion (Additional 26114) acquired at the same monastery.

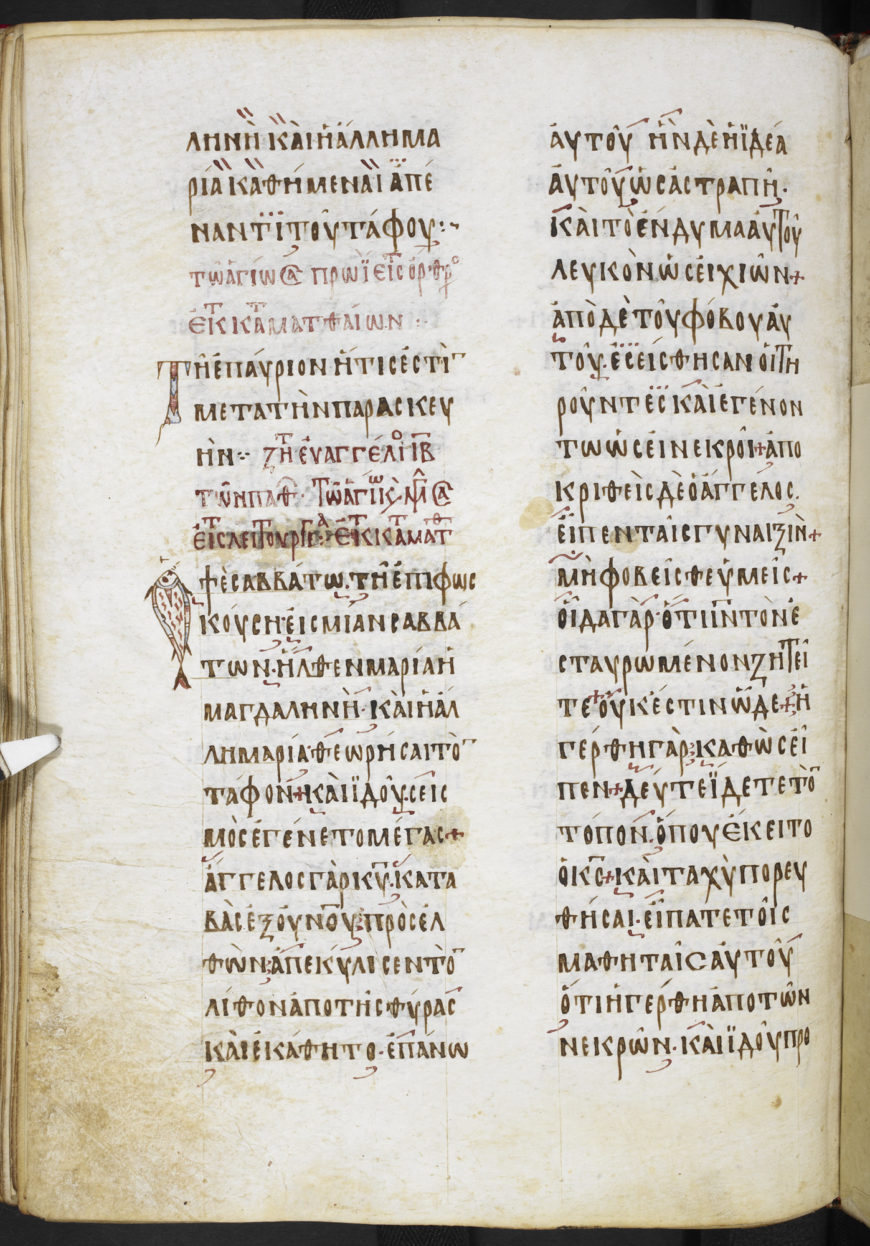

Finally, studies have shown that 36 manuscripts dating from the 9th to the 14th century can be assigned to the vast province of Asia Minor. From Bithynia, we have some 15 manuscripts dating from the 8th to the 14th century. Nicaea, one of the major cities of Bithynia, and provisional capital of the Empire during the Sack of Constantinople in 1204, was a major intellectual and artistic centre due to the presence of the elite of the fallen capital who were exiled there. It must have been an important centre for book production, even if no sources allow us to support this hypothesis. The British Library possesses two manuscripts from Smyrna dated to the 11th and 15th centuries (Harley 5559 and 5546), while Cappadocia is represented by Additional 39602, written in Ciscissa for the bishop Stephanos in 980. The text was corrected by Michael, a notary in Ciscissa, in 1049. It contains ornamental decoration, consisting of bands with plants and geometric motifs, and numerous decorated initials.

An initial omicron (O) in the shape of a fish can be seen on this page from a 10th-century Cappadocian Gospel lectionary (Add MS 39602), Cappadocian Gospel lectionary. Learn more about this item

Elisabeth Yota

Elisabeth Yota (Ph.D. in Art History and Archaeology) has been a lecturer at the University Paris IV Sorbonne since 2011. Her research focuses on Byzantine art and especially on liturgical illuminated manuscripts. She is author of Byzance, Une autre Europe (2006) and co-editor of Donation et Donors dans le monde byzantin (2012).

Originally published by The British Library.