Drawing from Greco-Roman and Near Eastern architecture of the ancient Mediterranean, this temple was one of history’s great architectural achievements.

Temple of Bel in 2005, Palmyra, Syria, first and second centuries C.E. (photo: ian.plumb, CC BY 2.0)

A noble city

Described as a noble city situated in a vast expanse of sand and renowned for its rich soil and pleasant streams, the ancient city of Palmyra was a stopping point for caravans traversing the Syrian Desert. [1] There is evidence that the site has been settled by people since the early second millennium B.C.E.

Known from ancient literary records—including Assyrian texts and the Hebrew Bible—Palmyra today is known as a unique and resplendent ruined city that preserves remarkable examples of monumental, hybrid architecture that blends the canon of Graeco-Roman architecture with Near Eastern elements.

Brief history

Palmyra, originally known as Tadmor, became a prosperous city under the Seleucid kings and was eventually annexed to the Roman empire after 64 B.C.E. Under Tiberius, the city was incorporated into the Roman province of Syria and assumed the name Palmyra. The city received the patronage of several Roman emperors and experienced great prosperity. The city suffered under the rise of the Sassanid dynasty of Persia. After the brief, revolutionary rise of queen Zenobia, the city was sacked by the Roman emperor Aurelian in 272 C.E.

View of Palmyra ruins from the Qala’at Shirukh hill in 2010 (photo: Varun Shiv Kapur, CC BY 2.0)

A hybrid architecture

The monumental architectural remains of the city attest to its great prosperity during its heyday. Among the many surviving monuments of Palmyra is the remarkable temple of the Semitic god Bel or Baal. A discussion of its architectural features demonstrates both the plurality of artistic and architectural styles in the ancient Mediterranean, and the numerous cultures that frequently overlapped and inter-mixed there. Although an inscription attests to the temple’s dedication in 32 C.E., its completion was gradual with major architectural elements added over the course of the first and second centuries.

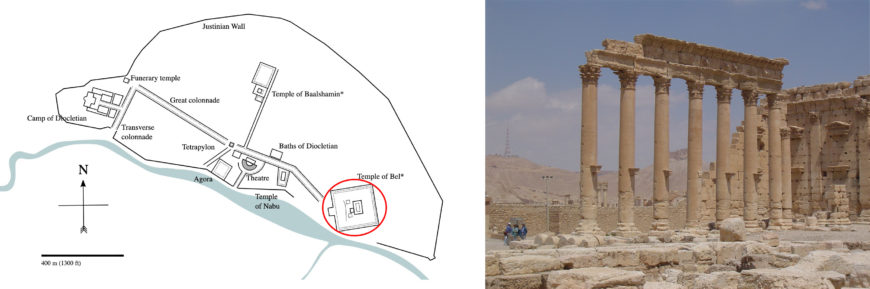

Left: Plan of the site of Palmyra, Syria, first and second centuries C.E. (image: MLWatts, CC0 1.0); right: Columns in the inner court of the Temple of Bel in 2005 (photo: ian.plumb, CC BY 2.0)

The organization of the temple’s ground plan derive from the traditions of eastern ritual architecture, including independent shrines for distinct divinities and, notably, the bent-axis approach to the cult (i.e. the architecture requires the celebrant to enter the temple and turn 90 degrees in order to view the offering table and cult area). The architectural elements employed in the temple’s elevation, however, derive from the Graeco-Roman canon, including the use of the Corinthian order as well as various architectural elements of that adorn the frieze course and roofline. In its outward appearance, the temple seems to derive from the canon of Hellenistic Greek architecture.

Palmyra’s divine triad: Baalshamin, with the Moon god Aglibol on his right and the Sun-god Yarhibol at left, 1st century C.E., limestone, 60 cm high, discovered at Bir Wereb, near Palmyra (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

The temple itself sits within a bounded, architectural precinct measuring approximately 205 meters per side. This precinct, surrounded by a portico, encloses the Temple of Bel as well as other cult buildings. The temple itself has a very deep foundation that supports a stepped platform. At the level of the stylobate the area measures 55 x 30 meters and the cella, stands over 14 meters in height and measures 39.45 x 13.86 meters.

The cella is designed according to the Near Eastern tradition of the bent-axis approach and incorporates two separate shrines (thalamoi). A ramp and central stair, with an off-center doorway, grants access to the cella. The columnar arrangement is pseduoperipteral and includes an arrangement of 8 x 15 (height = 15.81 meters) fluted, Corinthian columns. The cella also has exterior Ionic half-columns at each of its ends. Merlons (crenellations) crowded the roof and the ceilings were coffered. From masons’ marks and graffiti found on the site, it seems that there were craftspeople of various background, including Greeks and Romans alongside the Palmyrenes.

The temple is dedicated to a divine triad, Bel along with the moon god Aglibol and the sun god Yarhibol. This divine triad is innovative, with the secondary gods playing the role of Bel’s attendants.

Carved stone ceiling, cella, Sanctuary of Bel, Palmyra, Syria, first and second centuries C.E. (photo: John Winder, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Graeco-Roman + Near Eastern

Front view of triumphal (or monumental) arch at Palmyra, Syria, first and second centuries C.E. (photo: Erik Hermans, CC BY 2.0)

The Temple of Bel is one of the great architectural achievements of the Mediterranean world during the early first millennium. As an architectural product, it draws on rich, canonical forms derived from both the Graeco-Roman and Near Eastern spheres, and its technical aesthetics are of the first order. Along with temples such as that of Heliopolitan Zeus at Baalbek, the Palmyrene temple demonstrates the massive civic investment in monumental architecture.

Clearly, Palmyra was prosperous, allowing its elites to invest heavily in elaborate architecture—all the same this civic investment was also central to the Mediterranean concept of urbanism where presentation architecture helped to define and advance the status of the city itself. The hybridity of the Temple of Bel further demonstrates that ancient Palmyra was a multi-cultural community and that while the cult and its function adhered to Semitic practice, the execution of the temple in the Graeco-Roman style spoke the architectural lingua franca of the expansive Roman empire.

**The current political situation in Syria has resulted in the destruction of numerous archaeological sites at Palmyra, including the Temple of Bel.

Note:

[1] Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 5.88.1.

Additional resources

Read a Reframing Art History chapter about rethinking approaches to the art of the Ancient Near East until c. 600 B.C.E.

Palmyra on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.

Palmyra photo album on Flickr from the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World.

Palmyra, UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Pleiades Project: Palmyra, Tadmora or Hadrianopolis (Palmyra).

N. J. Andrade, Syrian Identity in the Greco-Roman World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Warwick Ball, Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire (London: Routledge, 2002).

K. Butcher, Roman Syria and the Near East (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2004).

Trevor Bryce, Ancient Syria: a Three Thousand Year History (Oxford University Press, 2014).

P. Collart and J. Vicari, Le Sanctuaire de Baalshamin à Palmyre: Topographie et architecture, 2 vols (Rome: Institut Suisse de Rome,1969).

Malcolm A. R. Colledge and Pascale Linant de Bellefonds, “Palmyra” Grove Art Online

L. Dirven, The Palmyrenes of Dura-Europos: A Study of Religious Interaction in Roman Syria (Religions in the Graeco-Roman World) (Leiden: Brill, 1999).

H. J. W. Drijvers, The Religion of Palmyra (Leiden: Brill, 1976).

Hugh Elton, Frontiers of the Roman Empire (London: Routledge, 1996).

C. F. Gates, Ancient Cities: the Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome, 2nd edition (London: Routledge, 2011).

M. Gawlikowski, Le temple palmyrénien: étude d’épigraphie et de topographie historique (Warsaw: Éditions scientifiques de Pologne, 1973).

P. Gros, L’architecture romaine: du début du iiie siècle av. J.-C. à la fin du Haut-Empire, (Paris: Picard, 1996).

Nigel Pollard, Soldiers, Cities, and Civilians in Roman Syria (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2000).

H. Seyrig, R. Amy and E. Will, Le Temple de Bel à Palmyre, 2 vols (Paris: Geuthner, 1975).

A. M. Smith, II, Roman Palmyra: Identity, Community, and State Formation (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013).

J. Starcky and M. Gawlikowski, Palmyre (Paris: Librairie d’Amérique et d’Orient, 1985).

J. B. Ward-Perkins, Roman Imperial Architecture (Yale: Yale University Press, 1981).

T. Wiegand et al., Palmyra: Ergebnisse der Expeditionen von 1902 und 1917 (Berlin: H. Keller, 1932).

E. Will, Les Palmyréniens: la Venise des sables: Ier siècle avant-IIIème siècle après J.-C. (Paris: A. Colin, 1992).