Temple from Group C, Mỹ Sơn sanctuary, 8th–12th century (photo: Gary Todd)

A sacred sanctuary of the Chams

Before the formation of modern-day countries in Southeast Asia, there were ancient kingdoms with magnificent temples. One location stands out—the Mỹ Sơn sanctuary, home of the Hindu gods. Today this is an archaeological site, but from the 4th to the 13th centuries this was a sacred site and featured more than seventy Hindu temples. Mỹ Sơn was built for the God Siva (also written as “Shiva”) who was associated with concepts of the mountain and father. At Mỹ Sơn, Siva had many manifestations in human form or as an aniconic (non-representational, abstract) symbol like the linga.

The Mỹ Sơn sanctuary was built by the Chams, who once dominated what is today southern Vietnam (Champa). The Chams are an ethnic group with historical records dating from the 4th century C.E. They created some of the most exquisite Hindu art and architecture found in Southeast Asia, blending Indic religions with their local culture.

For over a millennium, the Chams created political states from north of the Mekong Delta, which included much of what is Vietnam today. The earliest Mỹ Sơn temples no longer exist, but there are many surviving buildings and artifacts dated to the 7th–8th century.

B Group of Mỹ Sơn sanctuary, 4th–13th centuries

A tower-temple from Group C, Mỹ Sơn sanctuary, 8th–12th century (photo: Gary Todd)

This essay will focus on an altar-pedestal and lintel found in one of the surviving E Group temples (archaeologists have given letters to each temple to identify them). The Chams are known for their local construction of colossal altar-pedestals, a unique artistic production in Southeast Asia. The Mỹ Sơn E1 temples and artifacts (like the altar-pedestal) were commissioned by the King, and they demonstrate how the royal court was closely connected to the sacred realm. An altar-pedestal is exactly that—an altar, or place for worship, and a pedestal is a support for a sculpture.

E Group of Mỹ Sơn sanctuary, 4th–13th centuries

The altar-pedestal of the Mỹ Sơn E1

Of the seventy-one temples, just ten monumental examples are extant at the Mỹ Sơn complex. Each sacred temple forms a rectangular room, with an altar-pedestal at the center (called a garba-griha, or sanctum).

Altar-pedestal with god Skanda and two Ganesha sculptures (right to left), 7th–8th century, Mỹ Sơn E1, Vietnam, sandstone, H. 65 cm; W. 271 cm, D. 333 cm (Đà Nẵng Museum of Cham Sculpture; photo: Daderot, CC0 1.0)

One of the most impressive sacred monuments at Mỹ Sơn E1 is a 7th/8th-century altar-pedestal. I will talk about the symbolic image of Siva that once stood atop the pedestal, as well as relief sculptures on the pedestal itself.

The sacred altar-pedestal is decorated with Hindu subject matter and utilizes iconography (subjects and symbols) in a local Cham style. The Mỹ Sơn E1 altar-pedestal is best understood as a seat for the Hindu god Siva, and it was designed to resemble the mythological Mount Meru (the center of the universe), where the gods lived. This altar-pedestal was originally located within the temple chamber, the sacred meeting place for Siva and his royal worshippers.

This pedestal formed an enclosure marking of sacred space for the monumental Siva linga shrine that was located in the garba-griha (sanctum) of the Mỹ Sơn E1 temple—the innermost sanctuary of the temple where Siva resides in his form of the linga. The linga is no longer extant nor do we know what the original form of the linga looked like.

Altar-pedestal, 7th–8th century, Mỹ Sơn E1, Vietnam (Đà Nẵng Museum of Cham Sculpture; photo: Mya Chau)

There are two steps on one side of the Mỹ Sơn E1 pedestal that serve as a portal to a higher, sacred realm. The front panel of the lower step shows three male figures holding a ritual cloth. The central figure extends his right leg forward with his left leg is bent at the knee. Both of his hands are raised, as if he is lifting the platform, embracing the spiritual world above. Two figures flank the larger central figure, each bends their head back to look up at the higher realm. These postures imitate the bodily position and hand gestures of the central figure.

The upper register shows three figures again, but this time we see the central figure from behind. Still bent on one knee with the other leg extended forward, he holds the ritual cloth up in the air. The figures who flank him are rendered in profile and they carry bowls. It is not certain if the three figures were meant to represent the same figures as those on the lower stair.

Brahmins, musicians, and worshippers on the side of the E1 altar-pedestal (detail), 7th–8th century, Mỹ Sơn E1, Vietnam (Đà Nẵng Museum of Cham Sculpture; photo: Mya Chau)

Religious specialists

Female figures are notably absent, and there are three major types of male figures reoccurring on all four-sides of the Mỹ Sơn E1 pedestal. The first group depicts religious specialists who perform sacred activities. These include court brahmins (an elite caste, that includes priests, scholars, and teachers) and ascetics. We can identify the brahmins because they are clean-shaven and carry wisdom beads, and they are often rendered with a distinctive hairstyle. Brahmins are shown as active beings, moving their entire body or engaged in vocal performances such as chanting, singing, or speaking. The brahmins and ascetics depicted on the Mỹ Sơn E1 pedestal suggests that they were highly revered as advisors to the king and held immense power at the royal court.

Ascetic reading a religious manuscript on the side of altar-pedestal and makara (detail), 7th–8th century, Mỹ Sơn E1, Vietnam (Đà Nẵng Museum of Cham Sculpture; photo: Daderot, CC0 1.0)

Unlike the brahmins, the ascetics have long beards, and they are shown engaging in activities such as reading and meditating. On one side of the steps, we see an ascetic reading a religious manuscript. This scene indicates that religious specialists acquired knowledge from ancient texts, which circulated around Champa. Above the ascetic is a makara, which is a sea creature in Hindu mythology that serves as a guardian to doorways and is a common motif in Southeast Asia. The makara is carved with intricate decorative patterns, and forms the railings of the two steps.

Musician on the front left of altar-pedestal (detail), 7th–8th century, Mỹ Sơn E1, Vietnam (Đà Nẵng Museum of Cham Sculpture; photo: Daderot, CC0 1.0)

Dancing animal on the side of altar-pedestal (detail), 7th–8th century, Mỹ Sơn E1, Vietnam (Đà Nẵng Museum of Cham Sculpture; photo: Mya Chau)

Performing artists

The second group of male figures are performing artists. Musicians, dancers, and instrumentalists animate the pedestal, playing perpetual music from harps, drums, and flutes. They create a lively environment with continuous sacred music. The presence of musicians and dancers evokes an image of the dancing Siva in a religious space among brahmins and ascetics. Dancing animals move happily to the music.

Worshippers on the side of altar-pedestal (detail), with an ascetic teaching while a worshippers clasps his hands to his chest, 7th–8th century, Mỹ Sơn E1, Vietnam (Đà Nẵng Museum of Cham Sculpture; photo: Mya Chau)

Hindu worshippers

The third group of male figures are active Hindu worshippers. These figures mirror the actions of actual worshippers who used the ritual spaces at the temple. In one scene, an ascetic converses or teaches, while a second figure kneels in worship with hands together against his chest. These pious figures are depicted throughout the Mỹ Sơn E1 pedestal as eternal worshippers who ensure continuous worship of Siva. Worshippers are separated through borders decorated with elaborate floral patterns.

Overall, the performative figures of brahmins, ascetics, musicians, dancers, animals, and worshippers animate the pedestal and evoke the dancing Siva. The pedestal makes a fitting enclosure for the now-lost Siva linga where worshippers could honor the god in the innermost sanctum of the temple.

Brahma is seated on a lotus flower above the sleeping Visnu. Lintel, 7th–8th century, Mỹ Sơn E1, Vietnam (photo: Mya Chau)

A lintel of the Mỹ Sơn E1

The royal court’s connection to the sacred realm is made evident in a 7th/8th-century lintel that was once on the doorway of the Mỹ Sơn E1 temple housing the Mỹ Sơn E1 pedestal. Anyone entering the temple would have passed directly below it. The lintel depicts Visnu Anantasayana and the birth of Brahma. The lintel shows the two-armed Visnu (preserver and protector of the universe) lying under a naga king (a divine deity believed to be half-human and half-cobra). A brahmin appears behind Visnu, with his hands raised, perhaps to evoke or communicate with the deity. On top of the lintel, Brahma is seated, cross-legged on a lotus flower above Visnu.

While the shrine at the heart of the temple is dedicated to Siva, the combination of the Hindu deities Siva, Brahma, and Visnu represents the trimurti, or the triple deity of supreme divinity also revered at Mỹ Sơn. They form a triad of Hindu gods responsible for the preservation, creation, and destruction of the world. Before worshippers enter inside the Mỹ Sơn E 1 temple, the lintel reminds them of the birth of Brahma and of the sleeping Visnu, and the home of the Hindu gods. The goal is to visualize the honorable Siva who resides inside, on the altar-pedestal.

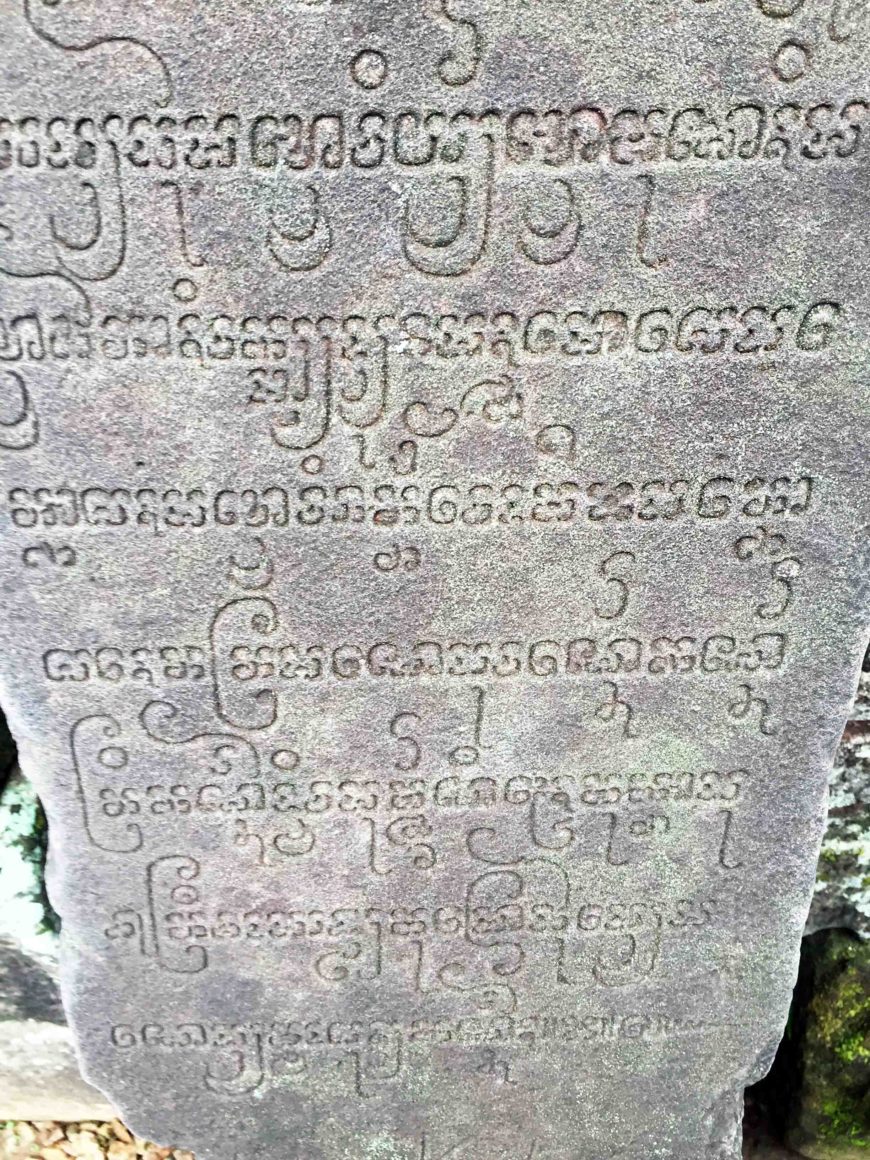

Inscriptions from Mỹ Sơn

The Mỹ Sơn temples and Mỹ Sơn E1 altar-pedestal are believed to be the sacred mountain of Siva, while the mountain is a metaphor for the home of Siva. Additionally, the temple is a symbol of the sacred mountain that is the home of the gods.

Several inscriptions found in Champa—all of them associated with temples—reveal the importance of temples and altar-pedestals in reference to a mountain. For example, the Mỹ Sơn Stele Inscription of Vikranatavarman (732 C.E.) reflects the association of altar-pedestals with mountains. It states:

Sri Naravahanavarman covered (that altar) of stone with gold and silver on the outside as Brahma made the peak of Meru. Moreover this altar, of gold and silver supporting Laksmi…shines like the peak of Himalaya. By him was made this great altar, difficult for the previous kings . . . how wonderful.

The inscription suggests that existing altar-pedestals in Champa once supported icons of other deities such as Laksmi, the goddess of fertility and wealth. Altar-pedestals, such as the Mỹ Sơn E1, are the home of the gods and a portal to communicate with them.

Altar-pedestal with god Skanda and two Ganesha sculptures (right to left), 7th–8th century, Mỹ Sơn E1, Vietnam (Đà Nẵng Museum of Cham Sculpture; photo: Daderot, CC0 1.0)

Mỹ Sơn today

Even with these few examples, it is clear how significant the Mỹ Sơn temple complex is in the history of Vietnam. In the 1940s, there were French efforts to restore Cham architecture, including the Mỹ Sơn temples. Unfortunately, in the late 1960s–1970s, the Vietnam War halted the restoration projects and excavations of Cham archaeological sites. During this war, the site of Mỹ Sơn became a battleground, and many of the Cham artifacts and temples were either demolished, looted, or damaged by U.S. bombings.

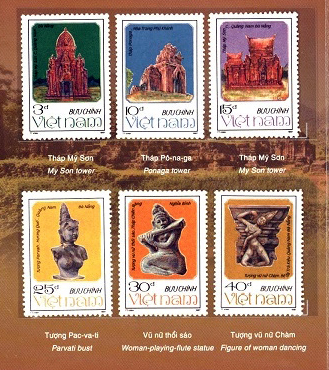

In 1987, the image of the Mỹ Sơn sacred temple complex and other Cham temple-towers was placed on postage stamps for letters that circulated in Vietnam and around the world. By 1999, the Mỹ Sơn sanctuary was declared a UNESCO world heritage site because it represents the extraordinary architectural achievements and artistic expressions of the Chams found in ancient southern Vietnam.