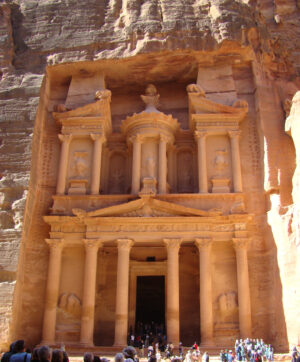

The so-called Treasury (Khazneh), Petra (Jordan), 2nd century C.E. (photo: Richard White, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The rock-cut façades are the iconic monuments of Petra. Of these, the most famous is the so-called Treasury (or Khazneh), which appeared in the film Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, as the final resting place of the Holy Grail.

The prominence of the tombs in the landscape led many early explorers and scholars to see Petra as a large necropolis (cemetery); however, archaeology has shown that Petra was a well-developed metropolis with all of the trappings of a Hellenistic city.

Tombs at Petra (Jordan) (photo: Dennis Jarvis, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Tombs

The tomb façades draw upon a rich array of Hellenistic and Near Eastern architecture and, in this sense, their architecture reflects the diverse and different cultures with which the Nabataeans traded, interacted, and even intermarried (King Aretas IV’s daughter was married to Herod Antipas, the son of Herod the Great, whose mother was also Nabataean). Many of the tombs contain niches or small chambers for burials, cut into the stone walls. No human remains have ever been found in any of the tombs, and the exact funerary practices of the Nabataeans remain unknown.

The dating of the tombs has proved difficult as there are almost no finds, such as coins and pottery, that enable archaeologists to date these tombs; a few inscriptions allow us to date some of the tombs at Petra, although at Egra, another Nabataean site (in modern Saudi Arabia), there are thirty-one dated tombs. Today scholars believe that the tombs were probably constructed when the Nabataeans were wealthiest between the second century B.C.E. and the early second century C.E. Archaeologists and art historians have identified a number styles for the tomb façades, but they all co-existed and cannot be used date the tombs. The few surviving inscriptions in Nabataean, Greek, and Latin tell us about the people who were buried in the tombs.

The Treasury (Khazneh), Petra (Jordan), 2nd century C.E. (photo: Richard White, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Hellenistic in style

The Treasury’s façade (24.9 meters wide x 38.77 meters high) most clearly embodies the Hellenistic style and reflects the influence of Alexandria, the greatest city in the Eastern Mediterranean at this time. Its architecture features a broken pediment and central tholos on the upper level; this architectural composition originated in Alexandria. Ornate Corinthian columns are used throughout. Above the broken pediments, the bases of two obelisks appear and stretch upwards into the rock.

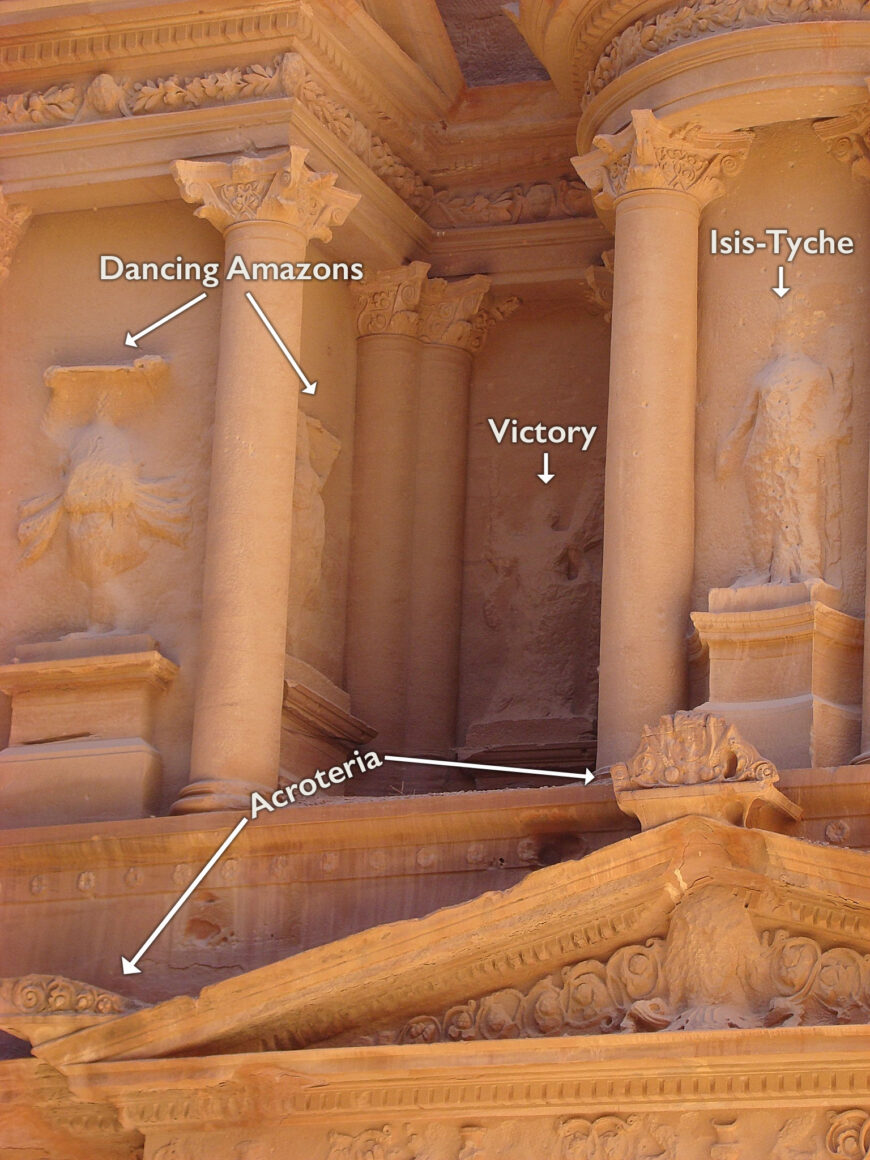

Relief sculptures of dancing Amazons, Victory, and a female figure presumed as Isis-Tyche, and acroteria (detail), The Treasury (Khazneh), Petra (present-day Jordan), 2nd century C.E. (photo: Richard White, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The sculptural decoration also underscores a connection to the Hellenistic world. On the upper level, Amazons (bare-breasted) and Victories stand, flanking a central female figure (on the tholos), who is probably Isis-Tyche, a combination of the Egyptian goddess, Isis, and Tyche, the Greek goddess of good fortune. The lower level features the Greek twin gods, Castor and Pollux, the Dioscuri, who protected travelers and the dead on their journeys. There are other details from the artistic traditions of the Hellenistic world, including eagles, the symbols of royal Ptolemies, vines, vegetation, kantharoi, and acroteria. However, the tomb also features rosettes, a design originally associated with the ancient Near East.

There are no inscriptions or ceramic evidence associated with the tomb that allows us to date it. Considering that it was located at the most important entrance to Petra through the Siq, it was probably a tomb for one of the Nabataean Kings. Aretas IV is the most likely candidate, because he was the Nabataeans’ most successful ruler, and many buildings were erected in Petra during his reign.

The treasury was exceptional for its figurative detail and ornate Hellenistic architectural orders; most tombs did not have figurative sculpture—a legacy of the Nabataean artistic tradition that was largely aniconic, or non-figurative. Many of the smaller tombs were less complex and also drew far less upon the artistic conventions of the Hellenistic world, suggesting that the Nabataeans combined the artistic traditions of the East and West in many different and unique ways.

It is a popular misconception that all of the rock-cut monuments, which number over 3,000, were all tombs. In fact, many of the other rock-cut monuments were living quarters or monumental dining rooms with interior benches. Of these, the Monastery (also known as ed-Deir) is most the famous. Even the large theater, constructed in the first century B.C.E., was cut into the rock of Petra.

So-called Monastery, or ed-Deir, Petra (Jordan) (photo: April Rinne, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Much like the Treasury (discussed above), ed-Deir was not a monastery, but rather behind its façade was a monumental cella with a large area for dining with a cultic podium at the back. While no traces of decoration remain today, the room would have been plastered and painted. The façade again features a broken pediment around a central tholos, but its decoration is more abstract and less figurative than that of the Treasury. The column capitals are typically Nabataean, modeled on the Corinthian order, but abstracted. The façade features a Doric entablature, but rather than having figures in the metopes, roundels with no decoration appear. Thus, while the Monastery deploys many elements of Classical architecture, it does so in a unique way.