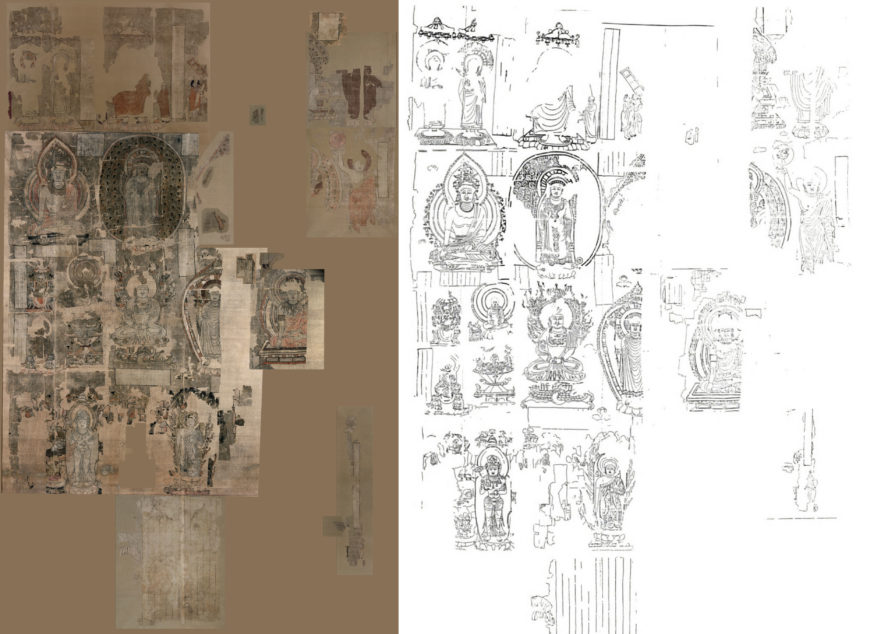

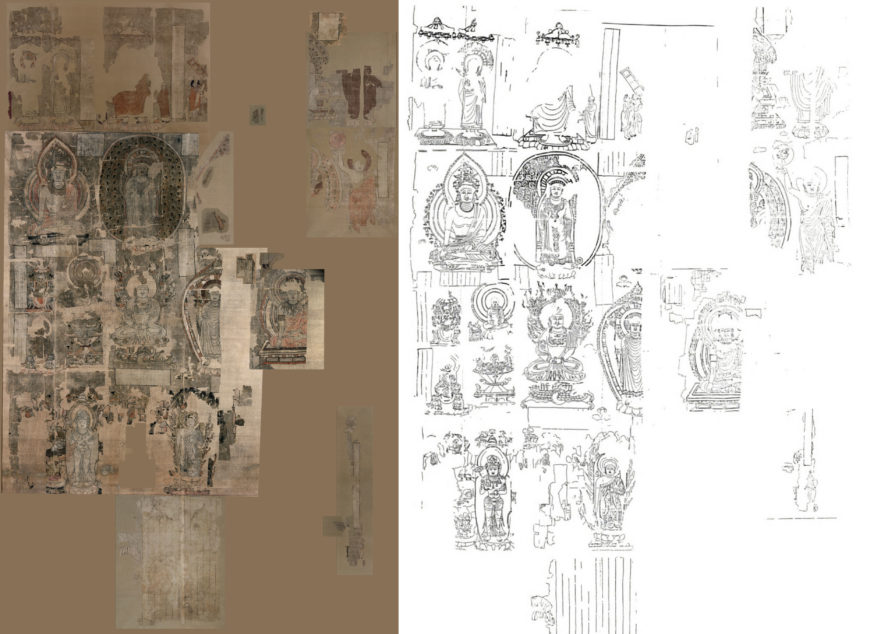

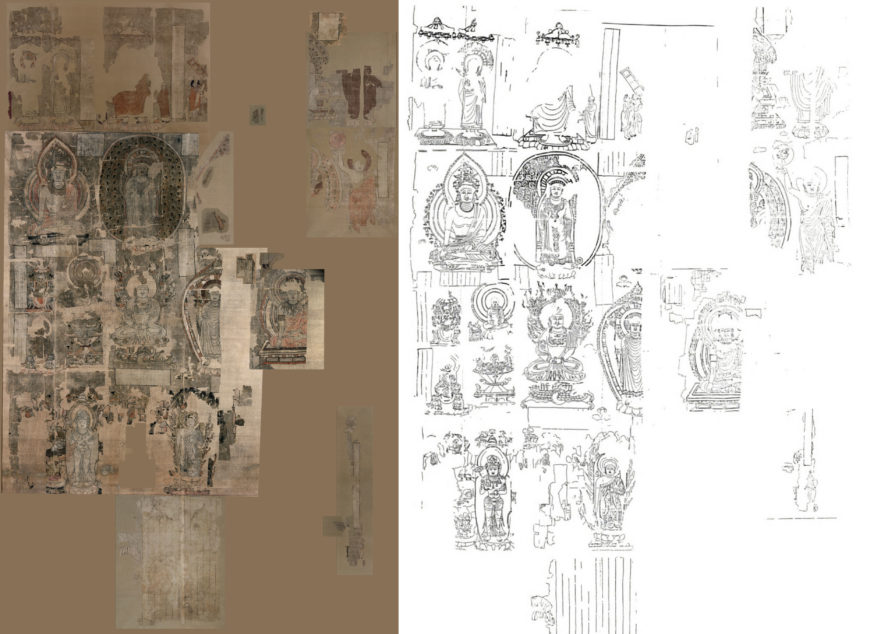

Reconstruction of the overall composition of the Dunhuang silk painting of auspicious images by Roderick Whitfield and The British Museum, 7th–8th centuries, Tang Dynasty, found in the “Library Cave” (Cave 17), Mogao grottoes, Dunhuang, Gansu province, China (Stein no.: Ch.xxii.0023). Left: painting fragments assembled together from The British Museum and National Museum, New Delhi, India; right: line-drawing by Roderick Whitfield, “Ruixiang at Dunhuang”, 1995, p. 152, fig. 2

How did medieval Chinese people imagine the transmission and localization of Buddhism, a religion originally from India? A one-of-a-kind painting (today in fragments in two museums) from Tang dynasty China (618–907 C.E.) helps us to understand how they imagined Buddhism coming to and transforming in China.

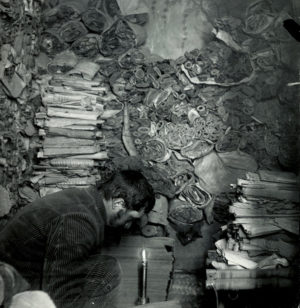

“The Dunhuang Library Cave” (Cave 17), Mogao Caves 16-17 (Library Cave), Dunhuang, Gansu Province, China, 862; sealed around 1000 (Photo courtesy of Dunhuang Academy)

The painting was found in fragments in one of the Buddhist cave-temples of Mogao (near the strategic oasis town of Dunhuang) along the Eastern Silk Road. Along with many other works, it was concealed for some nine hundred years behind the sealed entry of the cave-chapel now known as “the Dunhuang Library Cave” (Cave 17). The fragments were brought to London by archaeologist Aurel M. Stein at the beginning of the twentieth century, and were remounted and divided between the British Museum and the National Museum of India, New Delhi.

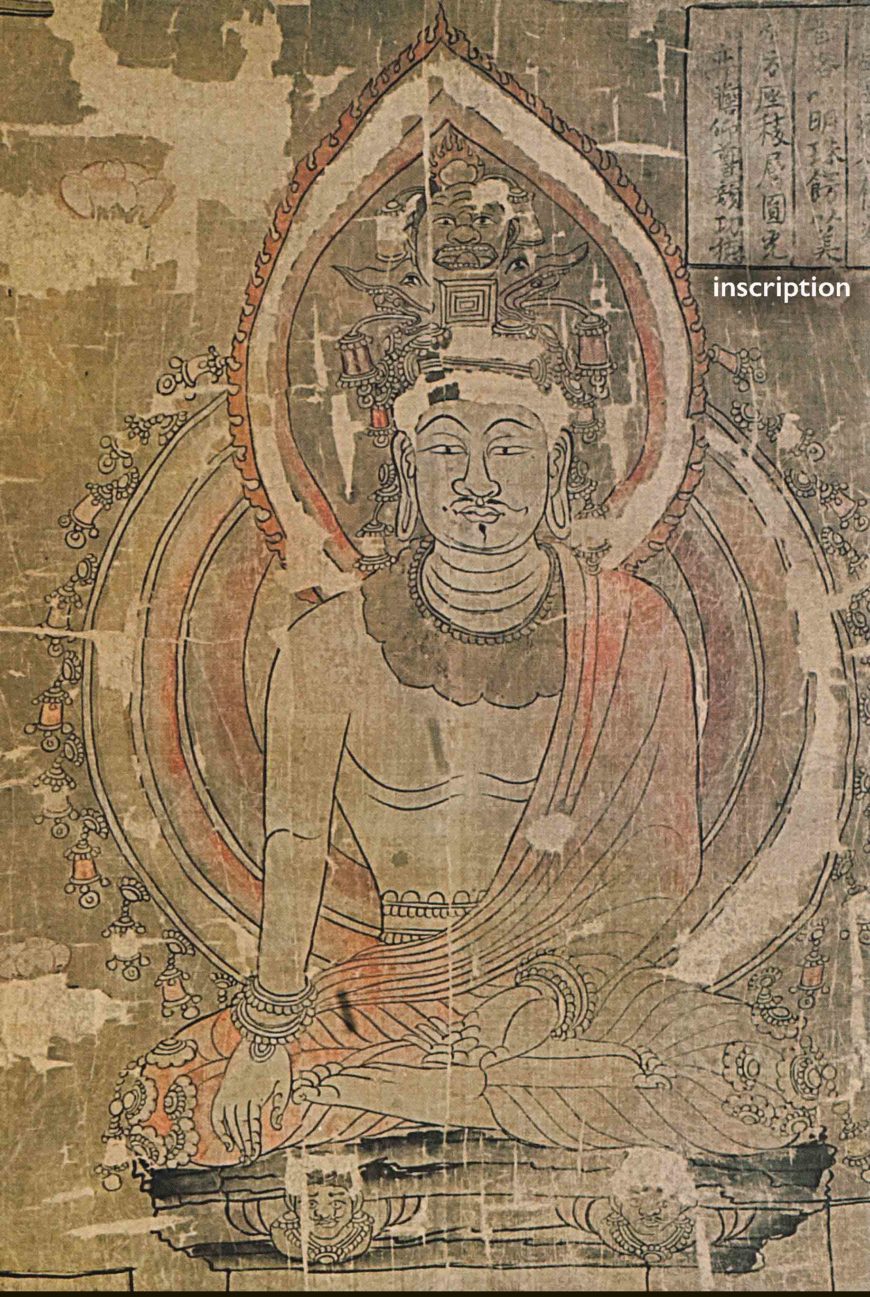

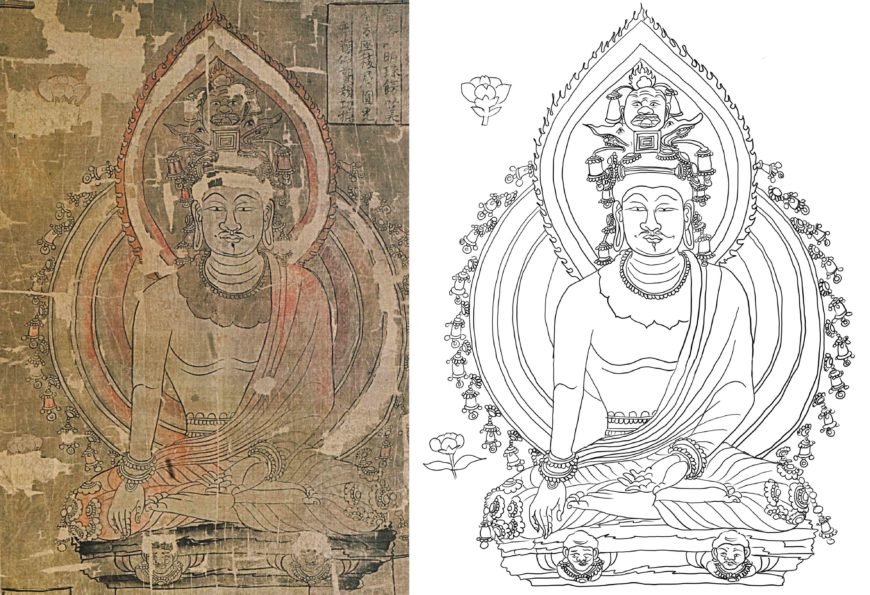

A seated buddha image with inscription top right (second row, first from the left in the reconstructed composition) from the Dunhuang silk painting of auspicious images, 7th–8th centuries, Tang Dynasty, found in the “Library Cave” (Cave 17), Mogao grottoes, Dunhuang, Gansu province, China (Stein no.: Ch.xxii.0023). Left: painting (National Museum, New Delhi); right: line-drawing by Zhenru Zhou

The painting’s fragmentary state, its division between two museums, and even the misplacement of parts of it during the remounting process, have obstructed the modern reconstruction of the painting’s overall pictorial composition. In addition, there remains little textual or archaeological information about its maker or patron, production place, function, or contexts of display. This silk painting therefore not only tells us about Buddhist art along the Silk Roads, but also about the complex life of an object after its creation.

The Dunhuang silk painting depicts numerous sacred Buddhist icons. In one, we see the bejeweled Shakyamuni Buddha at the moment before his enlightenment, when he performs the earth-touching mudra (hand gesture) with his right hand, invoking two earth spirits who are shown emerging from below his crossed legs as witnesses. This painted image references a sacred icon—what the accompanying inscription (top right) describes as “a light-emitting magical image”—that was once located near the Mahabodhi temple in the ancient Indian kingdom Maghada, and which was venerated, copied, and disseminated by Chinese pilgrim-monks, envoys, and artists who visited the sacred Buddhist sites in India.

There are other images of Buddha in the painting that are also copies of icons from India and elsewhere. Some of these images were believed to have performed miracles, such as emitting light or flying from India to Central and East Asia. Other icons shown in the painting refer to sacred sites or miraculous events that were enacted by Shakyamuni or other Buddhist deities. Because of their wondrous status, these icons and their copies were historically called “miraculous images” (ruixiang in Chinese). The representations that form the Dunhuang silk painting of auspicious images are therefore a composite of various types of miraculous images, revealing the multiple sources of wonder that medieval Chinese Buddhists looked to.

Fragments of the Dunhuang silk painting of auspicious images, 7th–8th centuries, Tang Dynasty, found in the “Library Cave” (Cave 17), Mogao grottoes, Dunhuang, Gansu province, China (Stein no.: Ch.xxii.0023) (National Museum, New Delhi)

Remounted fragments (not in correct order) of the Dunhuang silk painting of auspicious images, 7th–8th centuries, Tang Dynasty, found in the “Library Cave” (Cave 17), Mogao grottoes, Dunhuang, Gansu province, China (Stein no.: Ch.xxii.0023) (The British Museum)

Thanks to studies conducted by many scholars (including Alexander Soper and Roderick Whitfield), it is now clear that the painting originally consisted of approximately twenty iconic representations of buddhas and bodhisattvas arranged in four rows.

Reconstruction of the overall composition of the Dunhuang silk painting of auspicious images by Roderick Whitfield and The British Museum. Left: painting fragments assembled together from The British Museum and National Museum, New Delhi, India; right: line-drawing by Roderick Whitfield, “Ruixiang at Dunhuang”, 1995, p. 152, fig. 2

The original painting would have been three meters high by two meters wide. The images were executed in refined line-drawing with a light touch of color a the surface constructed from three and a half widths of plain silk sewn together and bordered by purple silk. The large size, the exquisite drawing, and the use of purple silk indicate the high status of this painting. As a unique work of Buddhist art, the painting combines historical references and stylistic elements from almost all major sites in Buddhist Asia, such as the Gandhara, Khotan, and China (both ancient and contemporary Tang). This painting is at once a repository of various images from Buddhist sacred geographies across India, Central Asia, and China as well as a testimony to the historical reception of Buddhist images in China.

A composite picture: foreign and local

While several images of icons in the painting are paired or set against a continuous landscape background, most are standalone images that vary in size, posture, costume, and ornament, as well as in the places and time periods associated with them. While acknowledging the foreign and local origins of the Buddhist sacred images, the painting visually presents them in a non-hierarchical way—no focal point, no perfect symmetry, and no clear axis.

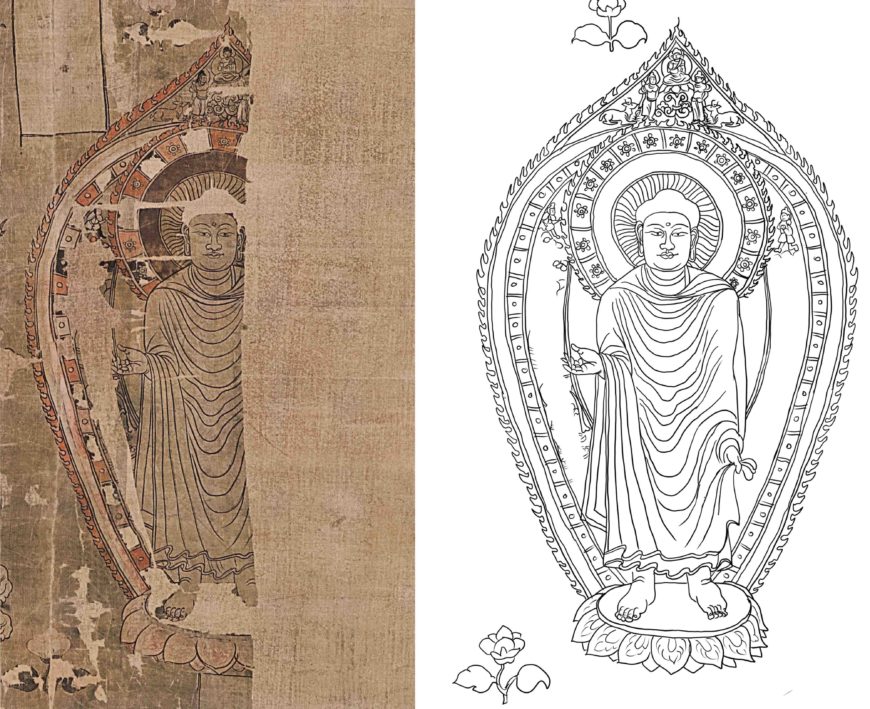

A standing Buddha

Dunhuang silk painting of auspicious images. In the reconstruction of the overall composition, the standing Buddha figure is in the third row, sixth from the left. Left: Fragment, Standing Buddha (detail), 7th–8th centuries, Tang Dynasty, found in the “Library Cave” (Cave 17), Mogao grottoes, Dunhuang, Gansu province, China (Stein no.: Ch.xxii.0023) (National Museum, New Delhi); right: line-drawing and theoretical restoration by author.

The painting fragments today in New Delhi represents miraculous images from both India and Central Asian sites. For example, if we look at a reconstruction that combines fragments located in both New Delhi and London, the standing buddha image is a pictorial record of a miraculous image in the Deer Park at Benares in India (no longer extant). The identification is indicated by a miniature scene in the pointed aureole where we see a preaching buddha flanked by bodhisattvas and deer, and an inscription that reads “Middle (India) Varanasi (Benares) country, Deer Park . . . image. . . .” [1]

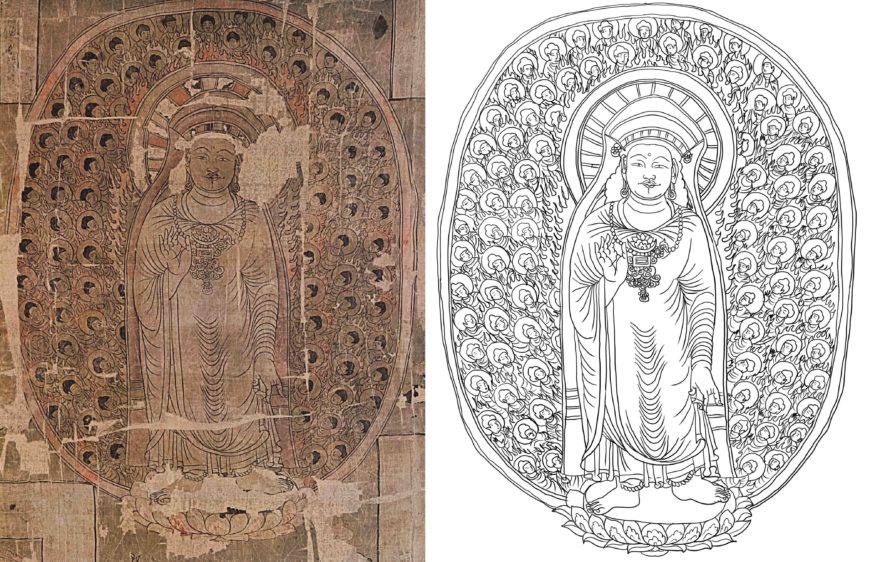

A standing buddha

Dunhuang silk painting of auspicious images. A standing buddha image. In the reconstruction, the figure is in the second row, second from the left. Left: painting (detail), 7th–8th centuries, Tang Dynasty, found in the “Library Cave” (Cave 17), Mogao grottoes, Dunhuang, Gansu province, China (Stein no.: Ch.xxii.0023) (National Museum, New Delhi); right: line-drawing and theoretical restoration by author

Another standing buddha image (in the reconstruction of the overall composition, this is the second one from the left on the second row) is enveloped by an elliptical aureole filled with three radiating layers of miniature standing buddhas. One of the possible identifications of this image is the Great Miracle at an ancient Indian city Śrāvastī, in which the Buddha divided his body into a myriad of bodies to dazzle the eyes of non-Buddhists; this is an instance where the silk painting refers to a sacred site and miraculous event. Another identification suggests it records a famous image that flew from Śrāvastī to Khotan, a renowned Buddhist city in “the Western Regions” as noted by the medieval Chinese.

Two standing buddha images

Dunhuang silk painting of auspicious images. Two standing buddha images. In the reconstruction, the figures are in the first row, first from the left. Left: painting (detail), 7th–8th centuries, Tang Dynasty, found in the “Library Cave” (Cave 17), Mogao grottoes, Dunhuang, Gansu province, China (Stein no.: Ch.xxii.0023) (The British Museum); right: line-drawing and theoretical restoration by author

In addition to the flying icon from the Western Regions, the fragments at the British Museum also show a few miraculous images from China. The leftmost image on the top row depicts a pair of buddhas standing under individual jeweled canopies and above a shared rectangular platform. The image has recently been identified as the stone buddhas that were found floating on a tributary of the Yangtse River that were enshrined in a Xuantong Monastery in 313 C.E.

A seated buddha

A seated buddha image. In the reconstruction, the figure is in the first row, second from the left. Left: painting (detail), 7th–8th centuries, Tang Dynasty, found in the “Library Cave” (Cave 17), Mogao grottoes, Dunhuang, Gansu province, China (Stein no.: Ch.xxii.0023) (The British Museum); right: line-drawing and theoretical restoration by author

The much-damaged image to its right represents a red-robe buddha sitting on a throne, attended by two worshipers. One of them has his head shaved and wears a long garment under the monk’s robe, suggesting he is a Chinese Buddhist monk. The barely legible inscription suggests that the image could be identified as an iron image of the Future Buddha Maitreya in Puzhou (in present-day Shandong province; it is no longer extant), which was cast by a monk called Huiyun and allegedly emitted golden light in 712 C.E. [2] All of these miraculous images of local, Chinese icons possess the same animated quality as the foreign ones. Many of the icons resemble prototypes that existed elsewhere, but this painting is unmatched because of the many images it contains.

A painting with many styles

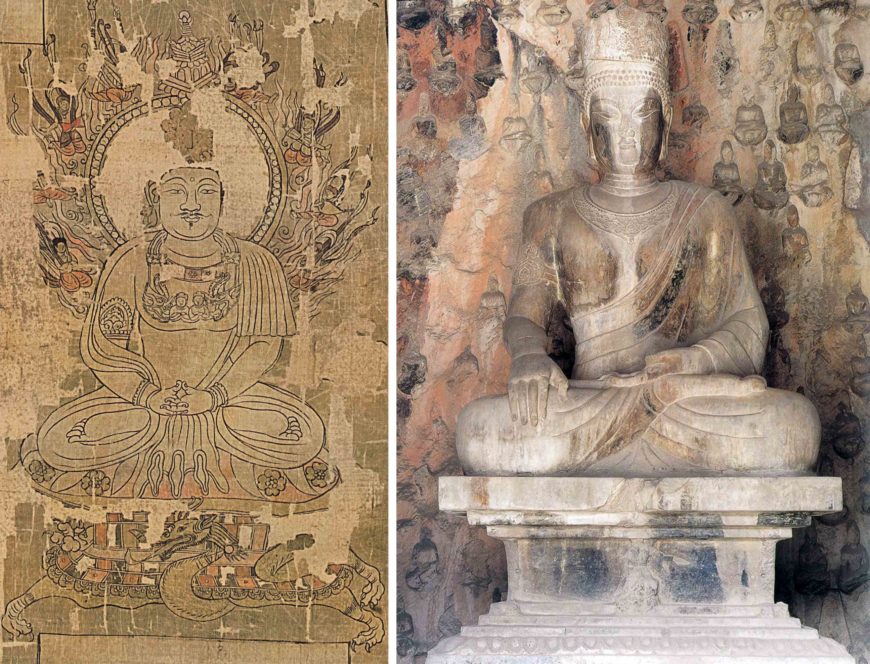

A seated bodhisattva on a dragon throne. In the reconstruction, the figure is in the third row, fifth from the left. Left: painting (detail), 7th–8th centuries, Tang Dynasty, found in the “Library Cave” (Cave 17), Mogao grottoes, Dunhuang, Gansu province, China (Stein no.: Ch.xxii.0023) (National Museum, New Delhi); right: line-drawing and theoretical restoration by author

The Dunhuang silk painting of auspicious images also includes a variety of styles associated with different places and time periods. Some figures, such as the bodhisattva seated cross-legged on a dragon throne (in the reconstruction, in the middle of the third row), exhibits a deliberate hybridity of styles. The bodhisattva wears an elaborate monster-headed necklace hung over an additional necklet.

Left: Standing Bodhisattva with Human-Figure Necklace, Kushan period, 2nd/3rd century, ancient region of Gandhara, phyllite, 150.5 × 53.3 × 19 cm (Art Institute of Chicago); right: A seated bodhisattva on a dragon throne image, 7th–8th centuries, Tang Dynasty, found in the “Library Cave” (Cave 17), Mogao grottoes, Dunhuang, Gansu province, China (Stein no.: Ch.xxii.0023) (National Museum, New Delhi)

Detail of necklace. Left: Standing Bodhisattva with Human-Figure Necklace, Kushan period, 2nd–3rd century, ancient region of Gandhara, phyllite, 150.5 × 53.3 × 19 cm (Art Institute of Chicago); right: A seated bodhisattva image, line-drawing and theoretical restoration by author

Both the necklace and necklet resemble Gandharan-style accessories depicted in a statue from the 2nd- or 3rd-century Gandhara. The Gandhara region (in present-day Pakistan) has some of the earliest known anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha (along with Mathura), and was under the rulership of the Kushan kings.

A seated bodhisattva on a dragon throne. In the reconstruction, the figure is in the third row, fifth from the left. 7th–8th centuries, Tang Dynasty, found in the “Library Cave” (Cave 17), Mogao grottoes, Dunhuang, Gansu province, China (Stein no.: Ch.xxii.0023) (National Museum, New Delhi)

Besides looking to Gandhara, the artist also looked to more local Chinese styles. The bodhisattva’s flaming aureole is flanked by four pairs of heavenly musicians and topped by a miniature stupa. It clearly refers to the sixth-century Chinese-style such as we see in a stone stele dated 544 C.E. that has a similar aureole design.

Left: Stele with seated Buddha (Maitreya) and attendant bodhisattvas, dated 544 (2nd year of Wuding reign), China, Alabaster, 55.9 cm × 32.4 × 20.3 cm; right: detail of the aureole (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The artist who painted the silk ingeniously combines the two styles through visual correspondence (similarity); the confronting winged figures hanging from the necklace visually echo the heavenly musicians with flying scarves who face each other.

Left: A seated bodhisattva on a dragon throne. In the reconstruction, the figure is in the third row, fifth from the left. Left: painting (detail), 7th–8th centuries, Tang Dynasty, found in the “Library Cave” (Cave 17), Mogao grottoes, Dunhuang, Gansu province, China (Stein no.: Ch.xxii.0023) (National Museum, New Delhi); right: Bejeweled Buddha in earth-touching gesture, Leigutai South Cave, Longmen, Tang Dynasty, c. 690–704, stone, 212 cm (image in the public domain)

Furthermore, the artist adapts these stylistic elements to adorn a plump body in the contemporary Tang style, which is exemplified by a bejeweled buddha image from the Longmen Caves. The line-drawing conveys a round face, and robustly modeled body and a reposeful gesture, which are characteristic of Tang sculpture.

Reconstruction of the overall composition of the Dunhuang silk painting of auspicious images by Roderick Whitfield and The British Museum, 7th–8th centuries, Tang Dynasty, found in the “Library Cave” (Cave 17), Mogao grottoes, Dunhuang, Gansu province, China (Stein no.: Ch.xxii.0023). Left: painting fragments assembled together from The British Museum and National Museum, New Delhi, India; right: line-drawing by Roderick Whitfield, “Ruixiang at Dunhuang”, 1995, p. 152, fig. 2

A picture about pictures

The silk painting is a composite of Buddhist images of heterogeneous origins shown all at once—in other words, it is a meta-picture (a picture about pictures) about Buddhist sacred images. What function would such a meta-picture have served?

One hint is in an inscription on the right of the Maghada image of a seated Buddha. This inscription has been translated as: “. . . Country of Maghada, light-emitting magical image. The eulogy of the picture says: This pictured form is noble and dignified. The head is spangled with bright pearls and adorned with lovely jewels. Square throne, cornered tiers, halo . . . the merit of looking up at the Blessed One’s face.” [3]

Although the description is generic and the writing is poorly preserved, this inscription reveals the migration of images across locations and media as well as the religious vows of the otherwise unvoiced patrons and artists. The expression “the eulogy of the picture” refers to a pictorial catalogue accompanied with eulogistic texts, which might be found in handscrolls or books. Its presence in the inscription suggests that the silk painting was copied after a now-lost, separate catalogue of miraculous images. This idea is supported by historical records that mention such pictorial catalogues being commissioned and circulated by Chinese pilgrims and envoys since the seventh century.

Image catalogues are thought to have been made for medieval Chinese Buddhists in the hope of accumulating religious merit by copying and “looking up at” miraculous images, however geographically remote they were. Even if these pictorial records of sacred icons were copies of copies, far from the original, the painting’s unknown artist has created a portable yet monumental painting that allows the viewer to confront miraculous images, regardless of their distance in both time and space.

Notes:

[1] Arthur Waley, A Catalogue of Paintings Recovered From Tun-huang By Sir Aurel Stein (London, 1931): 270.

[2] The much-faded inscription has been recently identified by Dunhuang scholar Zhang Xiaogang in Dunhuang fojiao gantonghua yanjiu (Study of the Paintings of Buddhist Correspondences in Dunhuang) (Lanzhou: Gansu jiaoyu chubanshe, 2015): pp. 296, 302-3.

[3] Arthur Waley, A Catalogue of Paintings Recovered From Tun-huang By Sir Aurel Stein (London, 1931): 268.

Additional resources:

Useful links: Digital Dunhuang Caves: https://www.e-dunhuang.com/. International Dunhuang Project: http://idp.bl.uk/. Database for Buddhist Cave Temples in China: Dunhuang Mogao Caves: http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/china-caves/dunhuang/.

Alexander C. Soper, “Representations of Famous Images at Tun-Huang.” Artibus Asiae, vol. 27, no. 4, 1964: pp. 349–364.

Aurel Stein, Serindia: Detailed Report of Explorations in Central Asia and Westernmost China (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1921): vol. 2, pp.1024–1026; vol. 4, pl. LXX.

Arthur Waley, A Catalogue of Paintings Recovered From Tun-huang By Sir Aurel Stein, K.C.I.E. (London: Printed by order of the Trustees of the British Museum and of the government of India, 1931): nos. LI, LVIII, and CDL; pp. 84, 95, 268–71.

Roderick Whitfield, “Ruixiang at Dunhuang”, in Function and meaning in Buddhist Art (edited by Kooij K R van and H van der Veere, Groningen: Egbert Forsten, 1995): pp.149–156, fig. 2.

Zhang Xiaogang, Dunhuang fojiao gantonghua yanjiu (Study of the Paintings of Buddhist Correspondences in Dunhuang) (Lanzhou: Gansu jiaoyu chubanshe, 2015): pp. 294–304, figs. 5–2-1~4.