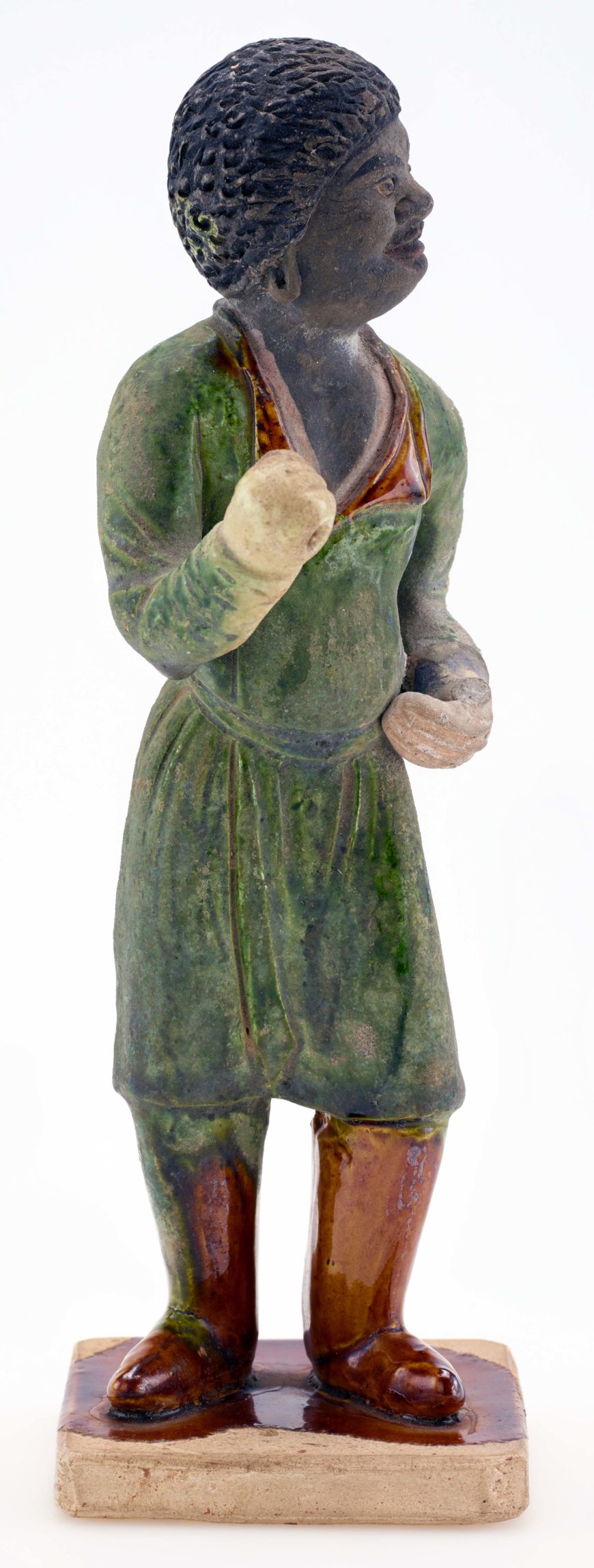

Tomb figure of a groom, Tang dynasty, c. 700–750, earthenware with lead-silicate glazes and painted details, China, 20.7 x 6.7 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1952.14)

The image is made of low-fired clay and depicts a standing male figure. He wears a long green coat with wide brown lapels, which is not a traditional Chinese-style garment. His high boots match the color of the lapels. The figure’s right arm is uplifted and pierced to hold a horse bridle, which has not survived. We can, however, identify him as a groom, one who attends to horses and stables. The groom’s “foreign” identity is obvious. He has dark skin, curly hair, heavy brows, prominent staring eyes, an exceptionally large nose, and thick lips. His facial features are so exaggerated that it seems as if he is making a face. The figure is covered by sancai, or “three color” glaze. His face is unglazed with painted details.

During the Tang dynasty (618–907), people of different races came to China from around the eastern hemisphere over the Silk Road (a network of land and sea trade routes that connected Asia, Europe, and East Africa). Some of them came to trade, and after making some money, they returned home; others, however, chose to settle permanently in big cities like Chang’an (the capital) and Luoyang. The latter group included grooms that managed the horses of the Tang elite. This standing figure represents such a groom from South or Southeast Asia. He could also be from East Africa, brought to China by Arab traders as a slave.

Representations of foreigners are often seen in Tang tomb figurines, demonstrating the cosmopolitan culture of the period. This sancai groom is especially interesting. He is dark-skinned yet dressed in Central Asian costume. Is it a fashion or an indication of a profession? Regardless, the appearance of the figure is a rich reflection of cultural intermixing in the Tang dynasty.

Sancai ceramics were restricted to the imperial and the elite. Their presence in tombs was a mark of high status. Figures of non-Chinese grooms suggest that the deceased was wealthy enough to have possessed imported horses and grooms, or at least aspired to have done so. A tomb figurine such as this standing groom not only tells us the high social status of its tomb owner but also provides an insight into the life of the deceased.

This resource was developed for Teaching China with the Smithsonian, made possible by the generous support of the Freeman Foundation

This resource was developed for Teaching China with the Smithsonian, made possible by the generous support of the Freeman Foundation

For the classroom

Discussion questions:

- Examine a topographical map of the eastern hemisphere. Map out possible sea or land routes that a groom from East Africa traveled to arrive in China. Compare your routes to a map of the Silk Road and Indian Ocean trade routes during the Tang dynasty.

- Why do you think the artisan chose to exaggerate the facial features of the sculpture? Why do you think this man is depicted in a stereotypical way?

- Based on what you know about this figure and the Tang dynasty, what can you infer about the person who was buried in the tomb where this figure was found? What might have been important to that person?