Frontal from the base of a funerary couch with Sogdian musicians and dancers and Buddhist divinities, Northern Qi dynasty, Period of Division, Northern Qi dynasty, 550–577, Grey marble with traces of pigment, China, Henan province, Probably Ce xian, 60.3 high x 234 x 23.5 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1915.110)

The Period of Division (220–589) refers to the four hundred years between the fall of the Han dynasty and the reunification of China by the Sui dynasty. Despite its political and social instability, this era witnessed a flourishing of culture, ideas, and art comparable to that of the European Renaissance.

After the Han dynasty fell in 220, China was divided into the Three Kingdoms of Wu, Wei, and Shu. In 280, the country was reunited under the unstable Western Jin dynasty. It was constantly invaded by non-Chinese nomadic groups from the north and eventually collapsed in 316. For over a century thereafter, the north was ruled by a succession of sixteen petty kingdoms led by different tribal groups until the Northern Wei dynasty brought the whole of north China under its rule in 439. Thereafter, China was split into two countries—the north and the south. China was divided into a series of states in the north and south and would not be reunited for almost 250 years. A large number of Chinese refugees migrated to the south, where the Chinese established the Eastern Jin dynasty with its capital in Nanjing. Four more dynasties ruled from Nanjing before the split between north and south was healed.

Western Paradise of the Buddha Amitabha, Northern Qi dynasty, 550–577, limestone with traces of pigment, China, Hebei province, Fengfeng, southern Xiangtangshan, Cave 2, 159.3 high x 334.5 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1921.2)

Buddha draped in robes portraying the Realms of Existence, Northern Qi dynasty, 550–577, limestone, China, probably Henan province, 151.3 high, x 62.9 x 31.3 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1923.15)

During this period, the dominant Confucian influence of the Han dynasty gave way to Daoism, which encouraged followers to comply with nature and not challenge natural patterns. Many intellectuals in the south accepted these ideas to escape from the chaos of the times. Buddhism became influential and gained power during this period, too. The Northern Wei rulers utilized Buddhism to better control the predominantly Chinese population. In the south, the first Buddhist temple was built in Nanjing in the third century, followed by almost five hundred temples by the sixth century.

The prevalence of Buddhism led to the construction of a number of Buddhist caves, including those of Dunhuang, Longmen, Yungang, and Xiangtangshan. Buddhist images were carved and painted on the cave walls. Monumental stone sculptures were cut from quarried sandstone and limestone and set up on temple altars or in temple courtyards. Buddhist art became a major category in Chinese painting as well.

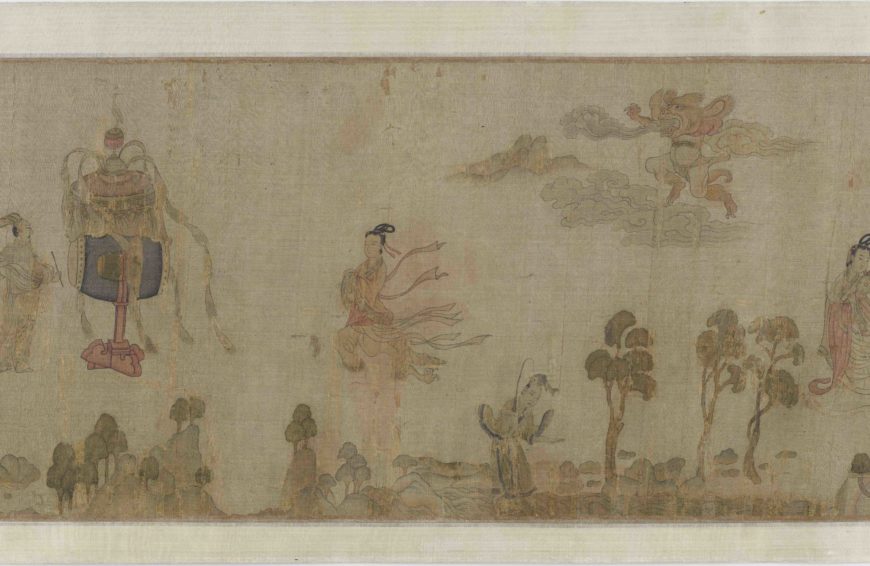

A Song dynasty copy of a work traditionally attributed to Gu Kaizhi (傳)顧愷之 (c. 344–c. 406), colophon by Dong Qichang 董其昌 (1555–1636), detail of Nymph of the Luo River, Southern Song dynasty, mid-12th to mid-13th century, ink and color on silk, China, 24.2 x 310.9 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1914.53)

These turbulent years also saw the birth of new aesthetic theories. Painters and poets began to think about the nature and spirit of artistic creation and expression, which led to the development of later figure and landscape painting. Individual artists began to gain attention, such as Gu Kaizhi (345–406). Calligraphy came to its full flowering. Considered the senior visual art form in China, it was appreciated for the beauty created by the brush writing.

A Song dynasty copy of a work traditionally attributed to Gu Kaizhi (傳)顧愷之 (c. 344–c. 406), colophon by Dong Qichang 董其昌 (1555–1636), detail of Nymph of the Luo River, Southern Song dynasty, mid-12th to mid-13th century, ink and color on silk, China, 24.2 x 310.9 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1914.53)

China was very open to outside influences during this period. Many parts of northern China were ruled by royal families of foreign origin. Foreign merchants, diplomats, and Buddhist missionaries streamed toward China across the Silk Road. Some settled in China but preserved their native customs and religions. Constant cultural exchanges between China and the West and relative political stability at the end of the period prepared the way for the arrival of the Tang dynasty (618–907), a time when trade and culture flourished.

This resource was developed for Teaching China with the Smithsonian, made possible by the generous support of the Freeman Foundation