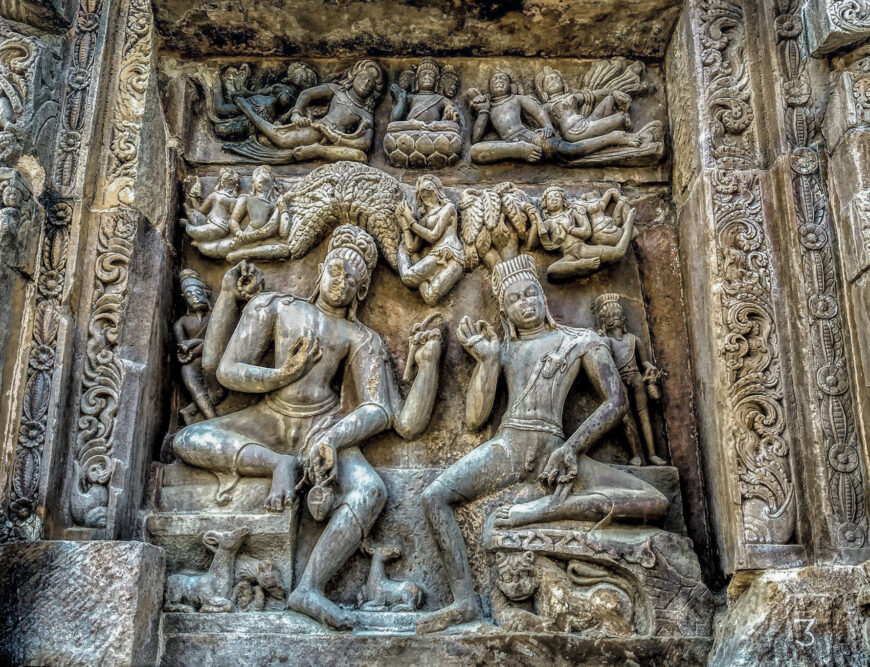

Nara and Narayana Seated Beneath a Tree (Naranarayana panel), Dashavatara Temple, Deogarh, India, 6th century (photo: Work2win, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Two figures sit, deep in meditation. The smooth rendering of their heavy-lidded eyes imparts a sense of tranquility to both figures. Deceptively realistic, on closer look, the curves in their torsos and sinuous twisting of their limbs are anatomically incorrect—the figure on the right, for example, presents the sole of his foot to the viewer in a contortion the human body is incapable of producing.

Anatomically inaccurate as it may be, the proportions and contours within these carvings produce an effect of dynamism, with the lines of the upper halves and lower halves of the figures’ bodies suspended in graceful dance-like poses. Their hands taper to slender fingers that, once again, do not conform to the limits of the human body. The artist has taken poetic license with the human form to create stylized poses.

The figures are possibly seated in a grove or forest. Framing the heads of both figures, we see a stylized rendition of branches laden with leaves. Underneath the figure on the right, a lion sits with its paws crossed, accompanied by deer-like creatures on the left. Although immediately recognizable as deer, here too, we see that the sculptor has given precedence to the fluidity of the carving over realistic precision, rendering one of the deer’s legs as folded to add dynamism to its composition. In the upper section of this tableau, we see figures—possibly representing celestial entities—whose diaphanous robes appear to be windswept, and whose bodies are suspended in space in a manner that gives them the appearance that they are flying. The rounded contours of the limbs of the figures—for example, the left arm of the figure on the right—along with the dancer-like poise and grace with which the figures are depicted, lends them a sense of agility.

This sculptural panel, known as the Naranarayana panel, depicts the twin sages Nara and Narayana, minor avatars of Vishnu (a principal Hindu deity) who were worshipped as separate deities associated with the protection of Dharma and righteousness. It appears on the eastern wall of the early 6th-century Dashavatara Temple in Deogarh, Uttar Pradesh.

The temple gets its name Dashavatara (meaning ten avatars) from the four sculptural panels on the exterior walls of the central shrine, which depict various avatars and aspects of the Hindu god Vishnu—including Nara and Narayana. These panels are well preserved and when viewed together, present a narrative that draws from Hindu mythology.

The Dashavatara Temple is considered to be one of the most accomplished examples of architecture in the Gupta Period (c. 320–647 C.E., named for the Gupta Dynasty). Under the Gupta Dynasty in North Central India, Hindu and Buddhist temples evolved from rock-cut shrines into structural temples, with elaborate carvings and carefully gridded plans. While we do not have information about the temple’s patrons, taking a closer look at it can help us understand how it marks an important moment in the stylistic trajectory of Hindu temple architecture.

South wall, Dashavatara Temple, Deogarh, India, 6th century (photo: Work2win, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Dashavatara Temple, Deogarh, India, 6th century (photo: byronic501, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Architectural aspects: a shikhara rising like a mountain peak

On approaching the archaeological remains of the Dashavatara Temple today, we see a central shrine in the shape of a square that sits on a raised square plinth (jagati) with stairs on each side.

Ruins of smaller shrines at each of the four corners of the plinth indicate that the temple followed a traditional layout scheme in Hindu temple architecture called panchayatana, literally meaning “five shrines,” in which the central, taller shrine is surrounded by four subsidiary shrines. Each of the corner shrines may have been dedicated to a different Hindu deity (though only their ruined bases remain, leaving little information about them).

The central shrine rises upwards in a strong vertical line. It forms a cube that is capped by the remnants of a shikhara (which translates to “mountain peak”), a pyramidal tower-like structure, originally about 40 feet tall with three stories of receding tiers.

While in earlier Gupta architecture, the defining characteristic of a temple was a cubical or square structure (which served as the central shrine) with a flat roof, we see a marked shift in the architecture of the Dashavatara Temple at Deogarh. The temple exhibits what is believed to be the first known instance of a shift towards the shikhara structure which would come to be widely regarded as a formative stage for Hindu temple architecture—a foundation that has influenced subsequent temple art and architecture in the Indian subcontinent for centuries to come.

The journey to enlightenment, set in stone

Each of the three exterior walls of the central shrine, as well as the doorway on the fourth wall, bears a different depiction of the Hindu god Vishnu, set in broad and deep central niches enclosed within elaborately carved frames.

Before entering the central shrine, devotees would most likely have circumambulated the shrine, making their way past the three main reliefs of Vishnu on the temple’s exterior walls. Through an analysis of these elements, we can trace a continuous thread of Vaishnava narratives and identify representations of the many avatars of Vishnu.

Entrance to the inside of the Dashavatara Temple, Deogarh, India, 6th century (photo: Ismoon, CC BY-SA 4.0). Watch a video of the doorway

Doorway

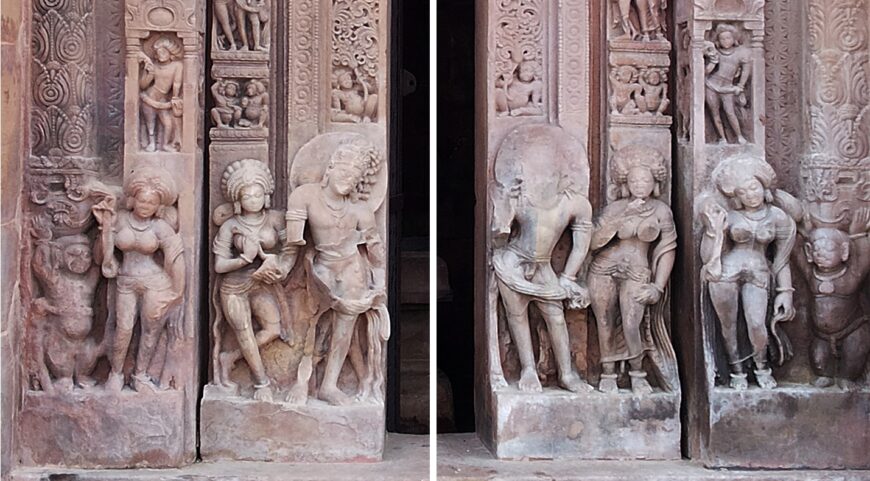

The entrance to the temple (which is on the west side) displays significantly more ornamentation than any previous examples of Hindu temples. It is framed by four courses of sculpture. At the base of each course are male and female attendants, flanked by floral ornamentation.

Figures (detail), entrance to the inside of the Dashavatara Temple, Deogarh, India, 6th century (photo: Ismoon, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The central panel above the doorway depicts the Hindu god Vishnu, to whom the temple is dedicated, in his manifestation as the four-armed Vasudeva. He is shown seated on the coils of the multi-headed serpent Shesha, holding a chakra (discus) in one hand and a shankha (conch shell) in the other, while a third hand is held in abhaya mudra and the fourth rests on his thigh.

Seated below on his right, massaging his feet is the presumed figure of his consort, the goddess Lakshmi; to his left and bottom right are his Narasimha avatar and Vamana avatar, respectively.

Southern wall

On the southern wall we see a depiction of the elephant-headed deity Ganesha symbolizing the overcoming of obstacles and auspicious beginnings, Ganesha was invoked at the beginning of worship and his presence on this wall suggests that the circumambulation may have begun at this panel, and could have been counter-clockwise, (starting in the South and ending at the West).

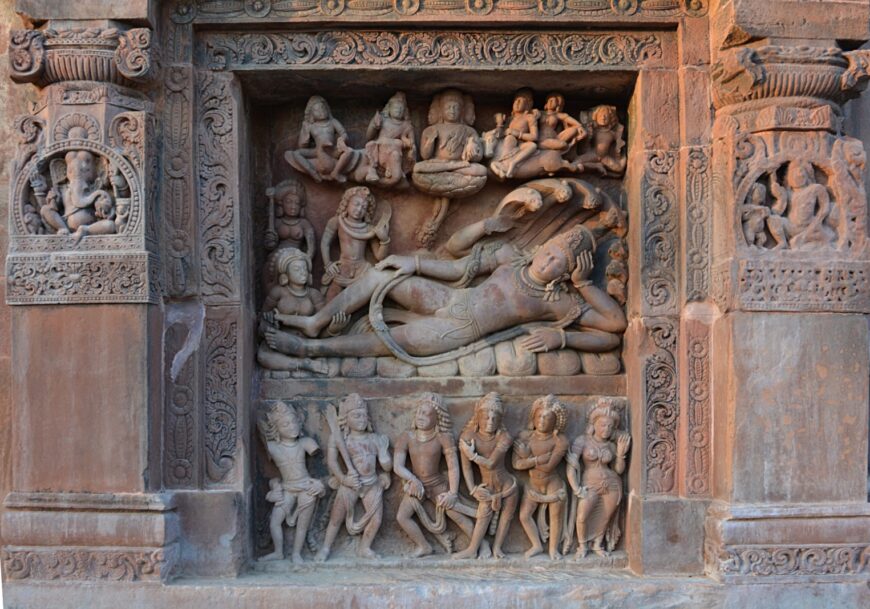

The central panel depicts Vishnu reclining on his serpent—whose coiled body resembles rocks—in an image known as Anantasayana. The many-hooded serpent forms a protective canopy above the god in his repose. This panel represents “the beginning” since it references the birth of the three-faced Hindu god, Brahma—the creator of the Universe in Hindu cosmology—seated on a lotus in the top center after emerging from the navel of Vishnu.

In the left corner we see Indra on his elephant mount and next Kartikeya, the Hindu deity associated with war, on his peacock mount. On the other side, Shiva and Parvati are seated on the bull Nandi. By Vishnu’s foot, we see his consort Lakshmi, and behind her, a whisk-bearing female attendant. Next to Lakshmi, and directly below Indra’s elephant, we see a personified Garuda, Vishnu’s eagle mount.

Eastern wall

Moving along the circumambulatory path, towards the eastern wall, devotees come across the Naranarayana panel depicting the twin sages. The saints—Nara to the right and a four-armed Narayana to the left—are shown in deep meditation, holding rosaries in their hands and seated on rocks amidst the wilderness of an ashram, or hermitage representing the aspect of Vishnu associated with the renunciation of worldly desires in pursuit of righteousness.

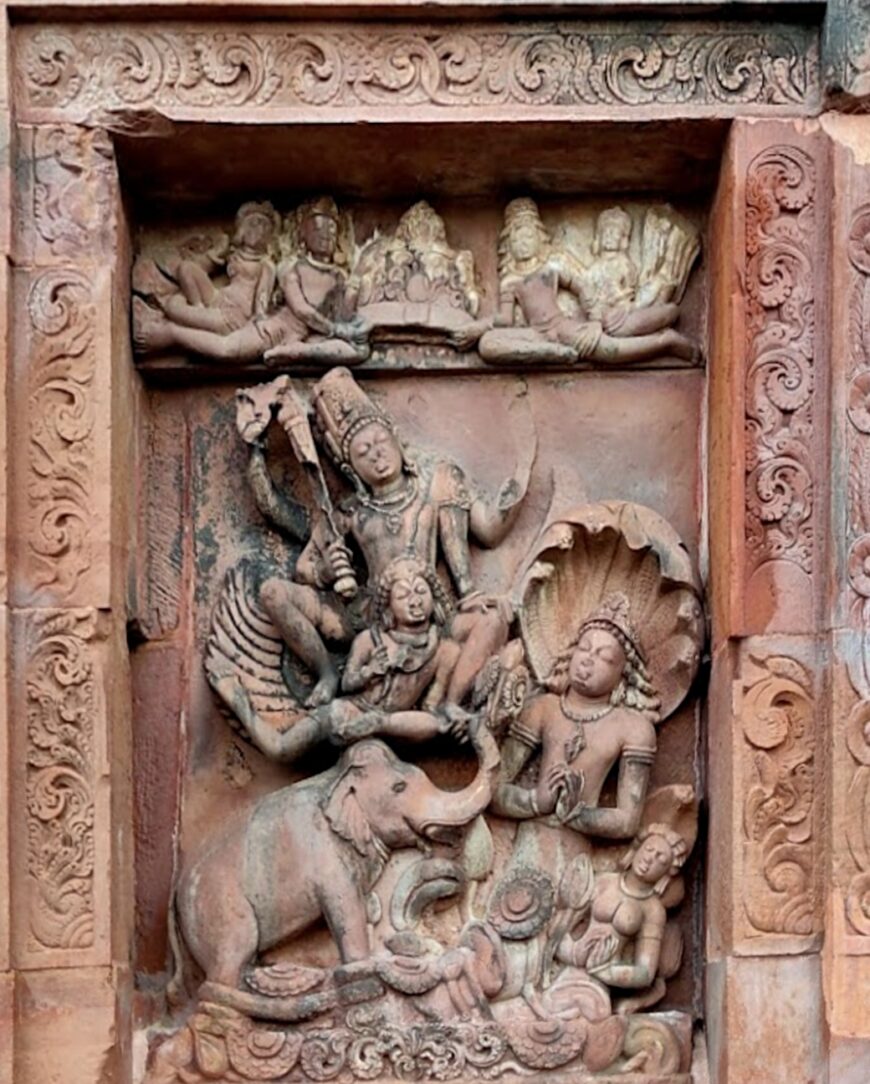

Relief depicting the Gajendramoksha scene, northern wall, Dashavatara Temple, Deogarh, India, 6th century

Northern wall

Further along the path, the niche on the northern wall contains a relief of the Gajendramoksha scene depicting Vishnu on his mount Garuda, wielding a mace in one hand and in the act of delivering the elephant-king Gajendra from the coils of a many-headed serpent. Standing beside Gajendra are the serpent couple Naga and Nagi, with their faces framed by serpent hoods, and their hands folded towards Vishnu in a gesture of submission or prayer.

According to the mythological episode that the panel is based on, the tussle between the creature and the elephant lasted for a millennium before the elephant finally invoked Narayana—one of the manifestations of Vishnu—and was saved.

Vishnu on the doorway and walls

Some scholars interpret the four depictions of Vishnu on the doorway and exterior walls of the shrine as a realization of the chaturvyuha, a state in which he assumes four different aspects of his divine nature: as creator, preserver, savior, and destroyer of the world.

The sequential arrangement of the reliefs could also symbolize progressive enlightenment and the attainment of moksha, liberation from samsara (the cycle of death and rebirth). This interpretation is based on the circumambulation ending with the Gajendramoksha panel, where in surrendering in prayer to Vishnu, the elephant is liberated from being reborn.

Representing the Gupta ideal

This temple has enormous historical and architectural value. Often discussed in the context of other early Gupta Period temples (such as the Parvati and Bhumara temples in Madhya Pradesh), the Dashavatara Temple is the earliest fully structural temple in north India to possess a shikhara. In comparison to older Gupta temples known to us, its ambitious architecture, as well as its complex and cohesive sculptural program exemplifies characteristics that would become the norm for subsequent examples of Nagara temples such as the Lakshmana Temple, Khajuraho in present-day Madhya Pradesh—marking it as a high point in the development of Hindu temple art and architecture.

Additional resources

Gajendramoksha in the Map Academy Glossary

Roy C. Craven, Indian Art: a Concise History (London: Thames and Hudson, 2006).

J.C. Harle, The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994).

Susan L. Huntington and John C. Huntington, The Art of Ancient India: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 2014).

Alexander Lubotsky, “The iconography of the Viṣṇu temple at Deogarh and the Viṣṇudharmottarapurāṇa,” Ars Orientalis (1996), pp. 65–80.

Michael W. Meister, “Geometry and Measure in Indian Temple Plans: Rectangular Temples,” Artibus Asiae, volume 44, number 4 (1983), pp. 266–96.

Michael W. Meister, “Prāsāda as Palace: Kūṭina Origins of the Nāgara Temple,” Artibus Asiae, volume 49, numbers 3/4 (1988), pp. 254–80.

Madho Sarup Vats, The Gupta Temple at Deogarh: Memoirs Archaeological Survey of India, number 70 (Delhi : Manager of Publications, 1952).

Drawing from articles on The MAP Academy