Periods of Byzantine history

Early Byzantine (including Iconoclasm) c. 330 – 843

Middle Byzantine c. 843 – 1204

The Fourth Crusade & Latin Empire 1204 – 1261

Late Byzantine 1261 – 1453

Post-Byzantine after 1453

Isidore of Miletus & Anthemius of Tralles for Emperor Justinian, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (Istanbul), 532-37 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

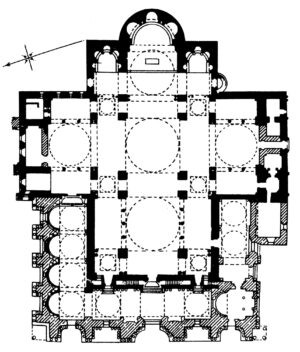

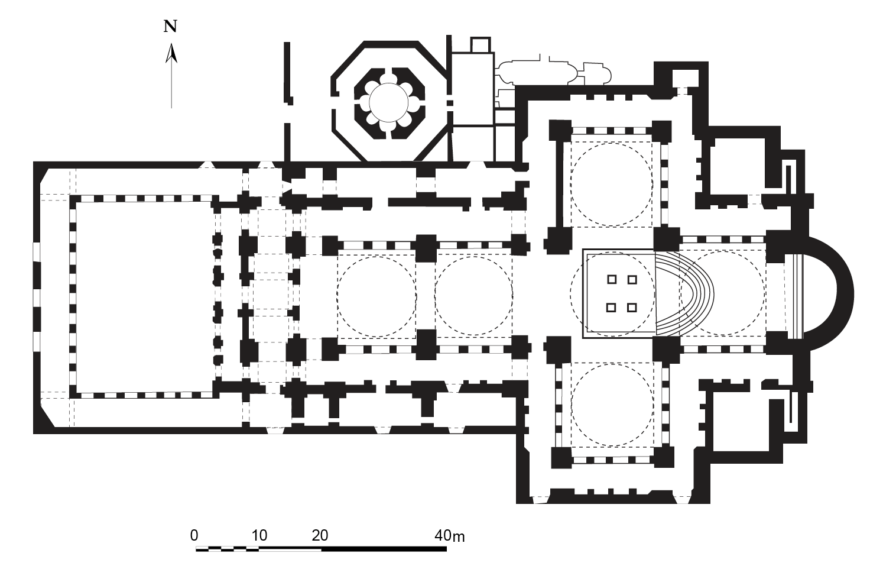

Plan of church of the Theotokos, c. 484, Mt. Gerizim (in modern Israel) (adapted from Schneider)

New trends

Although standardized church basilicas continued to be constructed, by the end of the fifth century, two important trends emerge in church architecture: the centralized plan, into which a longitudinal axis is introduced, and the longitudinal plan, into which a centralizing element is introduced.

The first type may be represented by the ruined church of the Theotokos on Mt. Gerizim (in modern Israel), c. 484, which has a developed sanctuary bay projecting beyond an aisled octagon with radiating chapels; the second by the so-called Domed Basilica at Meriamlik (on the southern coast of Turkey), c. 471-94, which superimposed a dome on a standard basilican nave (view plan). Both may be attributed to the patronage of emperor Zeno.

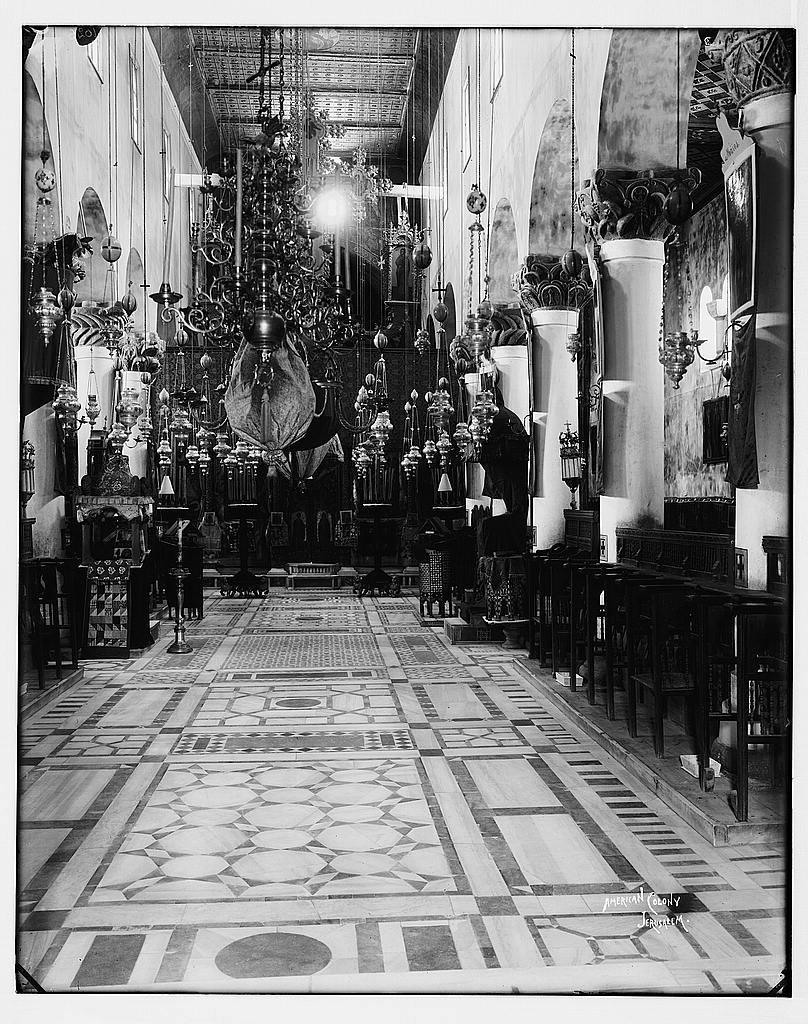

Sts. Sergius and Bacchus (Küçük Ayasofya Camii), Constantinople (Istanbul), completed before 536 (photo: © Robert G. Ousterhout)

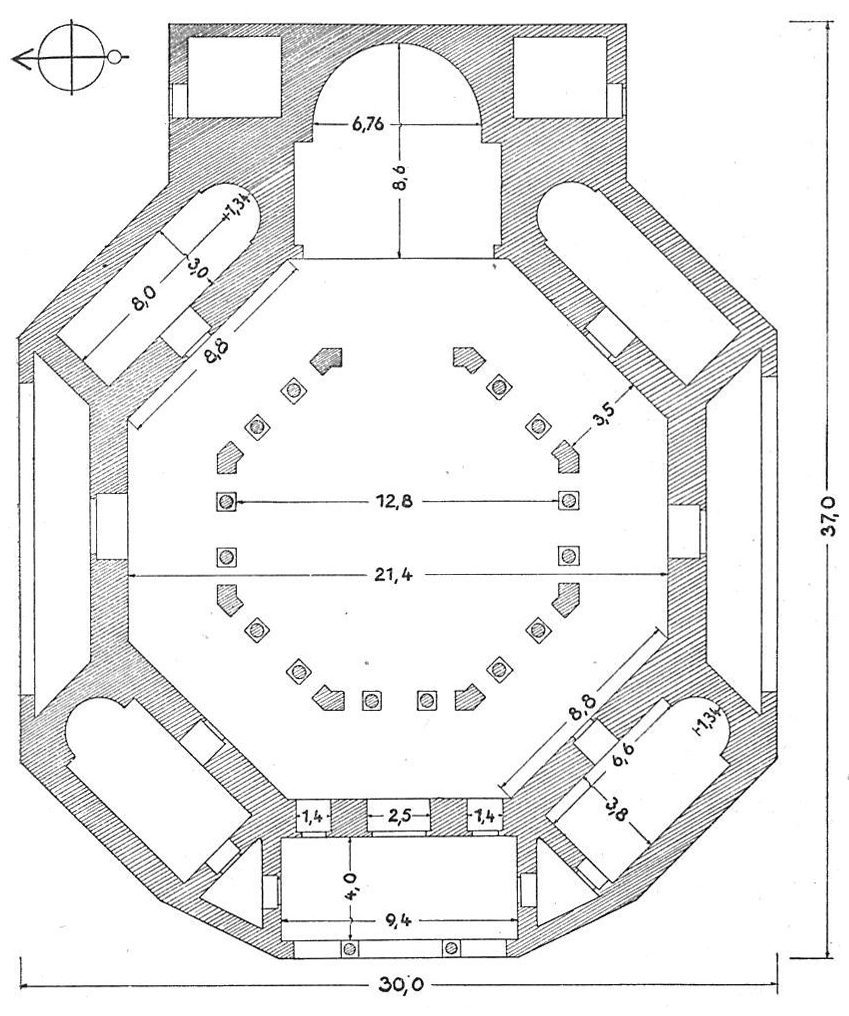

Plan of Sts. Sergius and Bacchus (Küçük Ayasofya Camii), Constantinople (Istanbul), completed before 536 (© Robert G. Ousterhout, redrawn after J. Ebersolt and A. Thiers, Les Églises de Constantinople, 1913)

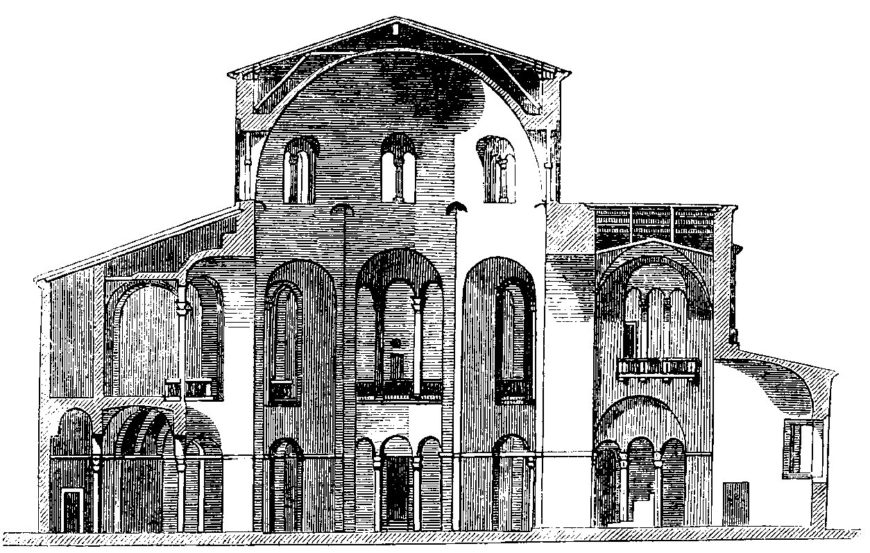

Section of San Vitale, Ravenna, from James Fergusson, The Illustrated Handbook of Architecture, vol. 2 (London: John Murray, 1855), 513

The reign of Justinian

Both trends are further developed during the reign of Justinian (reigned 527 to 565). HH. Sergios and Bakchos in Constantinople, completed before 536, and S. Vitale in Ravenna, completed c. 546/48, for example, are double-shelled octagons (view plan of San Vitale) of increasing geometric sophistication, with masonry domes covering their central spaces, perhaps originally combined with wooden roofs for the side aisles and galleries.

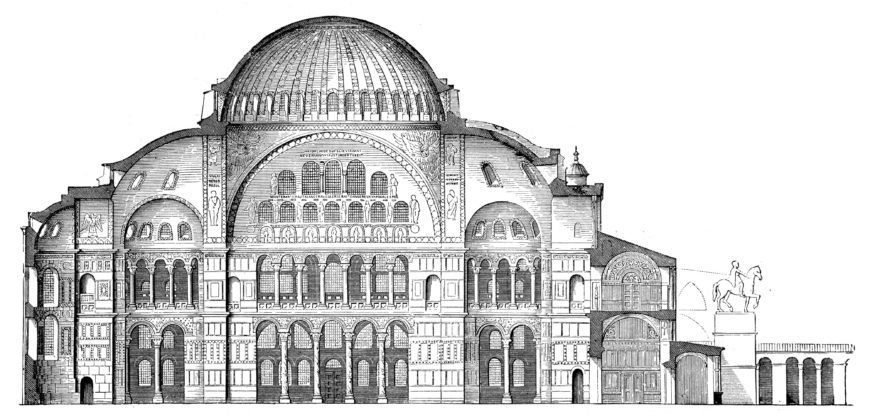

Section of Hagia Sophia by Isidore of Miletus & Anthemius of Tralles for Emperor Justinian, Istanbul, 532-37, from Wilhelm Lübke / Max Semrau: Grundriß der Kunstgeschichte. 14. Auflage. Paul Neff Verlag, Esslingen, 1908 (view annotated section)

Hagia Sophia, Constantinople

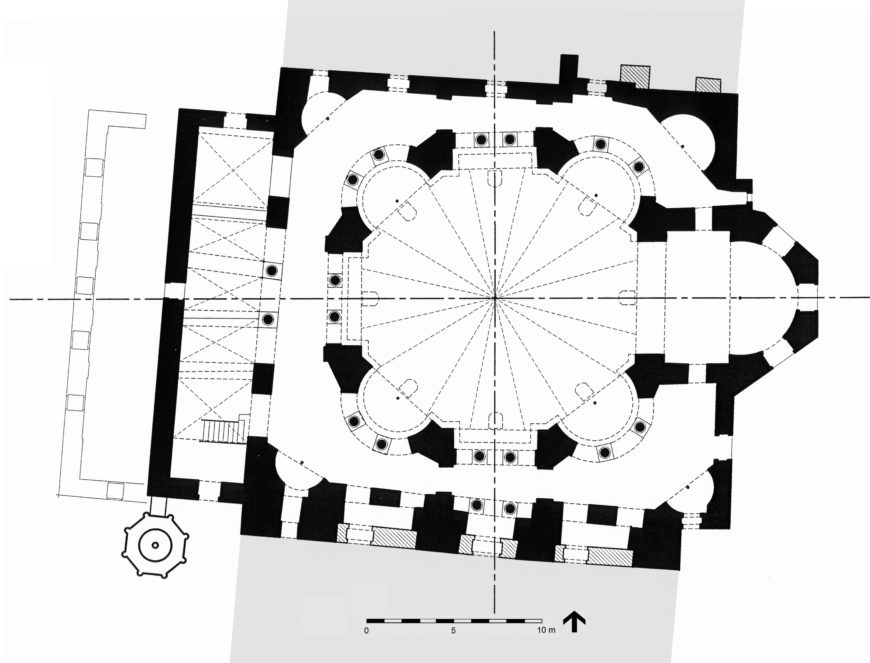

Several monumental basilicas of the period included domes and vaulting throughout, most notably at Hagia Sophia, built 532-37 by the mechanikoi Anthemios and Isidoros, which combines elements of the central plan and the basilica on an unprecedented scale.

Isidore of Miletus & Anthemius of Tralles for Emperor Justinian, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (Istanbul), 532-37 (photo: © Robert G. Ousterhout) (view annotated photo)

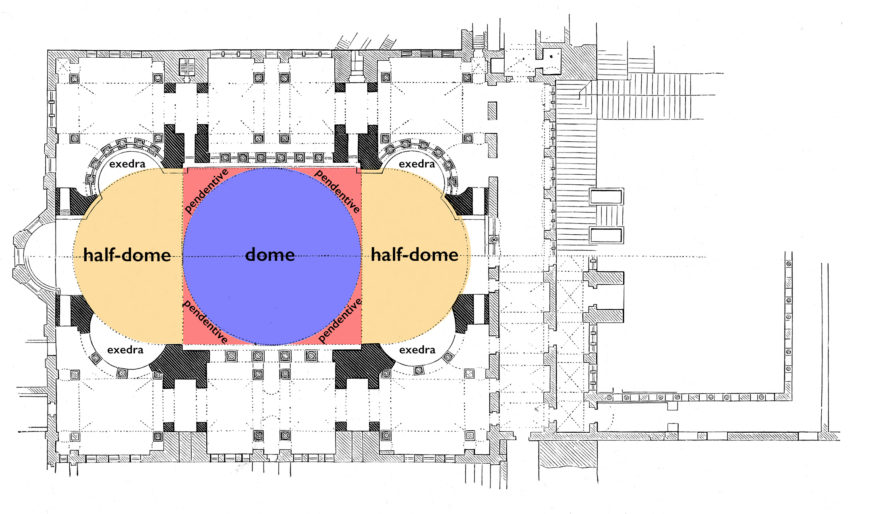

Its unique design focused on a daring central dome of slightly more than 100 feet in diameter, raised above pendentives, and braced to the east and west by half-domes. The aisles and galleries are screened by colonnades (rows of columns), with exedrae (semicircular recesses) at the corners. Following the innovative trends in Late Roman architecture, the structural system concentrates the loads at critical points, opening the walls with large windows.

Floor plan of Hagia Sophia by Isidore of Miletus & Anthemius of Tralles for Emperor Justinian, Constantinople (Istanbul), 532-37, based on a diagram from Wilhelm Lübke / Max Semrau: Grundriß der Kunstgeschichte. 14. Auflage. Paul Neff Verlag, Esslingen, 1908.

With glistening marble revetments on all flat surfaces and more than seven acres of gold mosaic on the vaults, the effect was magical—whether in daylight or by candlelight, with the dome seeming to float aloft with no discernable means of support; accordingly Procopios writes that the interior impression was “altogether terrifying.”

H. Eirene, Constantinople

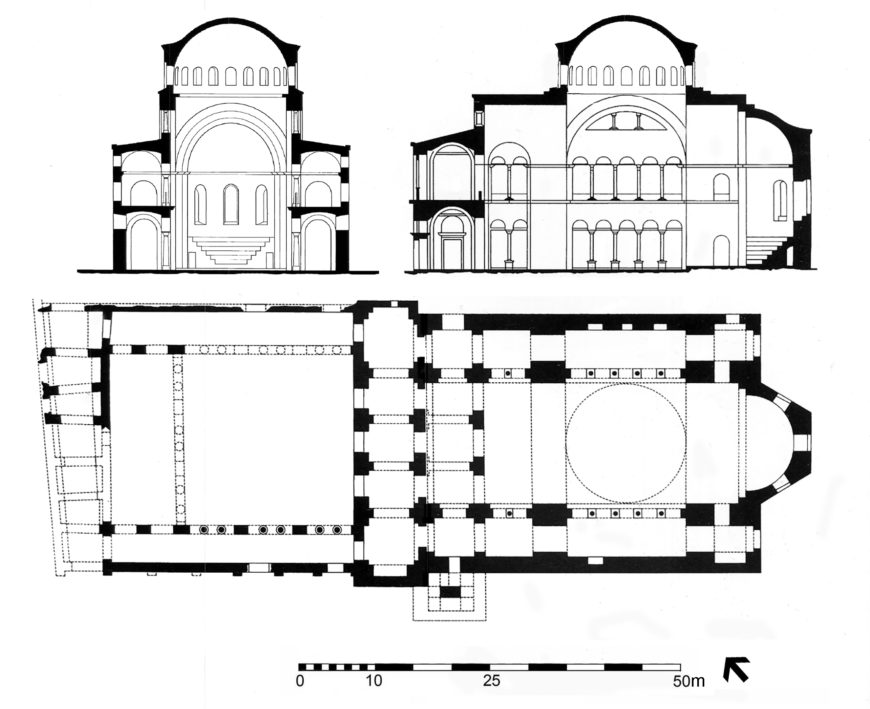

Related to H. Sophia are the domed basilicas of H. Eirene in Constantinople, begun 532, and ruined Basilica ‘B’ in Philippi (Greece), built before 540, each with distinctive elements to its design. The common feature in all three buildings was an elongated nave, partially covered by a dome on pendentives, but lacking necessary lateral buttressing. All three buildings suffered partial or complete collapse in subsequent earthquakes. Read about the redesign of H. Eirene after its collapse.

Hagia Eirene, Constantinople (Istanbul), plan and hypothetical sections of the sixth-century building (© Robert G. Ousterhout, adapted from S. Ćurčić, Architecture in the Balkans, 2010)

Hagia Sophia’s new dome

At H. Sophia, textual accounts suggest that the first dome, which fell in 557, was a structurally daring, shallow pendentive dome, in which the curvature continued from the pendentives, but with a ring of windows at its base.

A more stable, hemispherical dome replaced the original—essentially that which survives today, with partial collapses and repairs in the west and east quadrants in the tenth and fourteenth centuries.

Although H. Polyeuktos, built in Constantinople by Justinian’s rival Juliana Anicia, is normally reconstructed as a domed basilica—and thus suggested to be the forerunner of H. Sophia—it was unlikely domed, although it was certainly its predecessor in lavishness.

Reconstructed floor plan, church of St. John the Evangelist, Ephesus, drawn after Clive Foss, Ephesus after Antiquity: A late antique, Byzantine and Turkish City (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 1979. (Cordanrad, CC BY 3.0)

Five-domed churches

The spatial unit formed by the dome on pendentives could also be used as a design module, as at Justinian’s rebuilding of the church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople, in which five domes covered the cruciform building.

A similar design was employed in the rebuilding of St. John’s basilica at Ephesus, completed before 565, which because of its elongated nave took on a six-domed design.

The late eleventh-century S. Marco in Venice follows this sixth-century scheme.

The enduring basilica

In spite of design innovations, traditional architecture continued in the sixth century with the wooden roofed basilica continuing as the standard church type.

At St. Catherine’s at Mt. Sinai, built c. 540, the church preserves its wooden roof and much of its decoration. The three-aisled plan incorporated numerous subsidiary chapels flanking the aisles.

At the sixth-century Cathedral of Caricin Grad, the three-aisled basilica included a vaulted sanctuary area, with the earliest securely dated example of pastophoria: apsed chapels—known as the prothesis and diakonikon—which flanked the central altar area to form a tripartite sanctuary. This tripartite form that would become standard in later centuries.

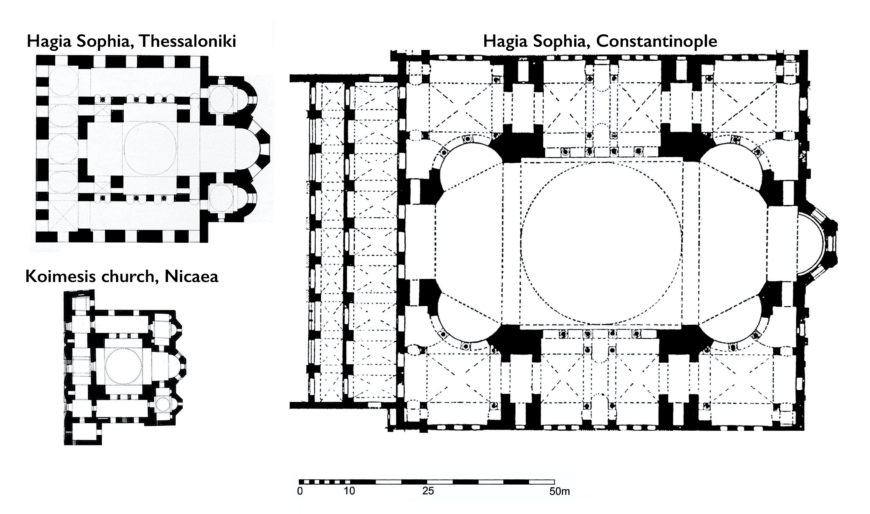

Plans drawn to the same scale, H. Sophia in Constantinople, H. Sophia in Thessaloniki, and the Koimesis church in Nicaea (© Robert G. Ousterhout)

Justinian’s legacy

Church types of the subsequent period tend to follow in simplified form the grand developments of the age of Justinian. H. Sophia in Thessalonikie for example, built less than a century later than its namesake, is both considerably smaller and heavier, as is the Koimesis church at Nicaea.

Both correct the basic problems in the structural design by including broad arches to brace the dome on all four sides.

The Caucasus

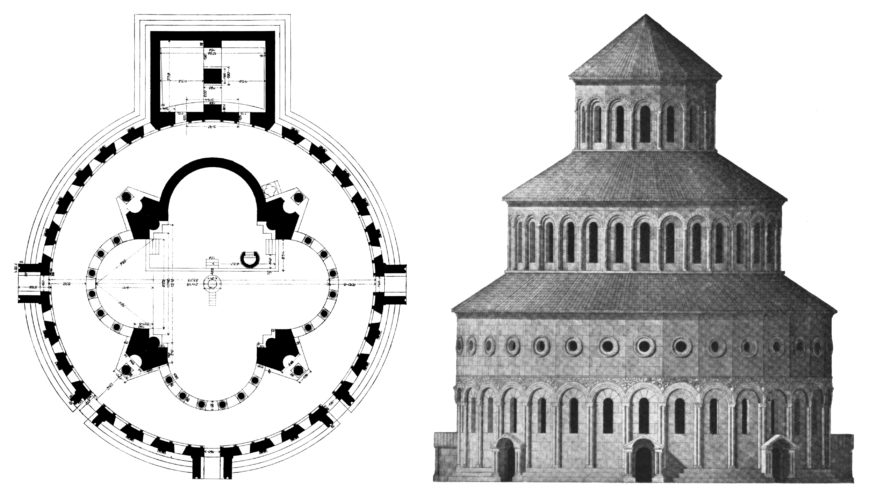

In the Caucasus, Georgia and Armenia witness a flourishing of architecture in the seventh century, with numerous, distinctive, centrally planned, domed buildings, constructed of rubble faced with a fine ashlar, although their relationship with Byzantine architectural developments remains to be clarified.

Left: exterior view of the church of St. Hripsime, Vagarshapat, 618 (photo: Rita Willaert, CC BY 2.0); Right: interior view of St. Hripsime (photo: Andrea Kirkby, CC BY-NC 2.0)

The domed church of St. Hripsime at Vagarshapat has a dome rising above eight supports, set within a rectangular building.

Church of the Cross, 586–604, Jvari (Mtskheta, Georgia) (photo: Mamuka Gotsridze, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The church at Church of the Cross at Jvari (Mtskheta) is similar, but with its lateral apses projecting. The aisled tetraconch church of Zvartnots stands out as following Byzantine, particularly Syrian, models.

Church of the Vigilant Powers (Zvart‘nots‘), Vagarshapat, plan and possible reconstructed elevations, from Josef Strzygowski, Die Baukunst der Armenier und Europa, vol. 1 (Vienna: A. Schroll & Co., 1918), figs. 112 and 119.

Next: read about Byzantine architecture during Iconoclasm

Additional Resources

Smarthistory’s free Guide to Byzantine Art e-book

Robert G. Ousterhout, Eastern Medieval Architecture: The Building Traditions of Byzantium and Neighboring Lands (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019)