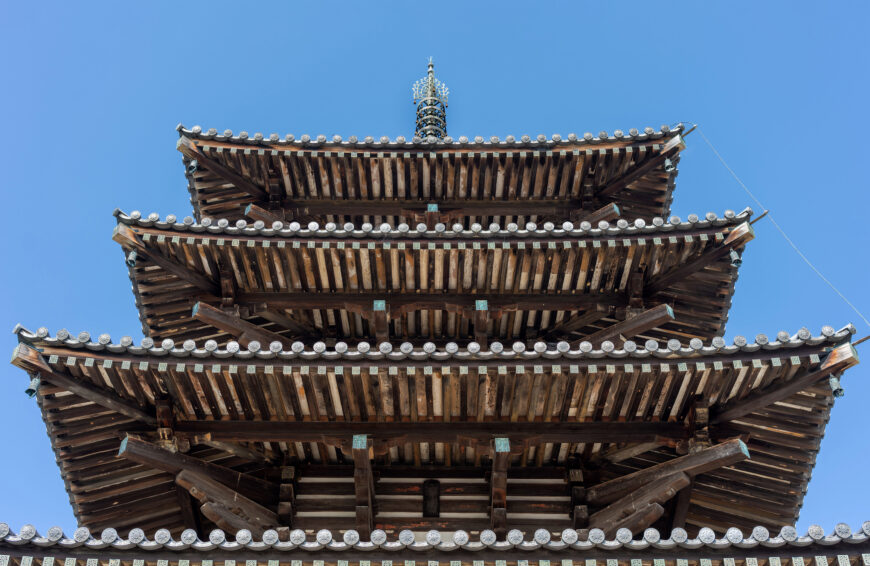

Longmen Caves, Luoyang, China (photo: xiquinhosilva, CC BY 2.0)

Imperial patronage

Worship and power struggles, enlightenment and suicide—the 2300 caves and niches filled with Buddhist art at Longmen in China has witnessed it all. The steep limestone cliffs extend for almost a mile and contain approximately 110,000 Buddhist stone statues, 60 stupas (hemispherical structures containing Buddhist relics) and 2,800 inscriptions carved on steles (vertical stone markers).

Buddhism, born in India, was transmitted to China intermittently and haphazardly. Starting as early as the 1st century C.E., Buddhism brought to China new images, texts, ideas about life and death, and new opportunities to assert authority. The Longmen cave-temple complex, located on both sides of the Yi River (south of the ancient capital of Luoyang), is an excellent site for understanding how rulers wielded this foreign religion to affirm assimilation and superiority.

Northern Wei Dynasty

Most of the carvings at the Longmen site date between the end of the 5th century and the middle of the 8th century—the periods of the Northern Wei (386–534 C.E.) through early Tang dynasties (618–907 C.E.). The Northern Wei was the most enduring and powerful of the northern Chinese dynasties that ruled before the reunification of China under the Sui and Tang dynasties.

The Wei dynasty was founded by Tuoba tribesmen (nomads from the frontiers of northern China) who were considered to be barbaric foreigners by the Han Chinese. Northern Wei Emperor Xiao Wen decided to move the capital south to Luoyang in 494 C.E., a region considered the cradle of Chinese civilization. Many of the Tuoba elite opposed the move and disapproved of Xiao Wen’s eager adoption of Chinese culture. Even his own son disapproved and was forced to end his own life. At first, Emperor Xiao Wen and rich citizens focused on building the city’s administrative and court quarters—only later did they shift their energies and wealth into the construction of monasteries and temples. With all the efforts expended on the city, the court barely managed to complete one cave temple at Longmen—the Central Binyang Cave.

Entrance to Central Binyang Cave, 508–523 C.E. Longmen Caves, Luoyang, China (photo: A1AA1A, CC0 1.0)

Central Binyang Cave

The Central Binyang Cave was one of three caves started in 508 C.E. It was commissioned by Emperor Xuan Wu in memory of his father. The other two caves, known as Northern and Southern Binyang, were never completed.

Imagine being surrounded by a myriad of carvings painted in brilliant blue, red, ochre and gold (most of the paint is now gone). Across from the entry is the most significant devotional grouping—a pentad (five figures—see image below).

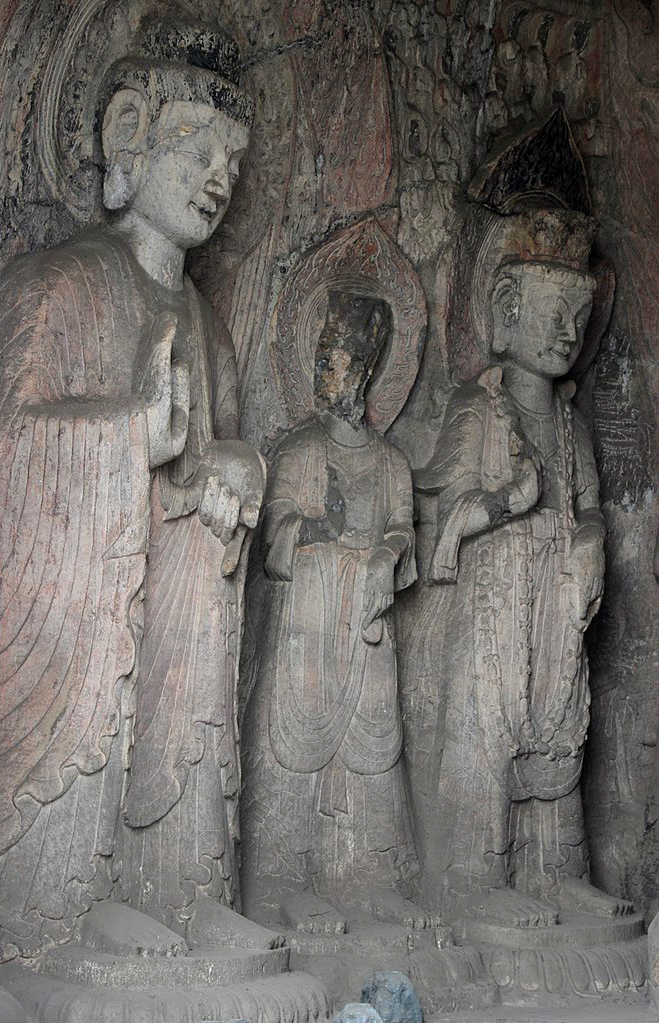

Pentad, Central Binyang Cave, 508–523 C.E., Longmen Caves, Luoyang, China (photo: Gary Todd, CC0 1.0)

Drapery, central Buddha (detail), Central Binyang Cave, 508–523 CE. Longmen Caves, Luoyang, China (photo: Gary Todd, CC0 1.0)

Bodhisattvas and disciples, Central Binyang Cave, 508–523 C.E., Longmen Caves, Luoyang, China, (photo: Gary Todd, CC0 1.0)

The central Buddha, seated on a lion throne, is generally identified as Shakyamuni (the historical Buddha), although some scholars identify him as Maitreya (the Buddha of the future) based on the “giving” mudra—a hand gesture associated with Maitreya. He is assisted by two bodhisattvas and two disciples—Ananda and Kasyapa (bodhisattvas are enlightened beings who have put off entering paradise in order to help others attain enlightenment).

The Buddha’s monastic robe is rendered to appear as though tucked under him (image above). Ripples of folds cascade over the front of his throne. These linear and abstract motifs are typical of the mature Northern Wei style (as also seen in this gilt bronze statue of Buddhas Shakyamuni and Prabhutaratna, from 518 C.E.). The flattened, elongated bodies of the Longmen bodhisattvas (image left) are hidden under elaborately pleated and flaring skirts. The bodhisattvas wear draping scarves, jewelry and crowns with floral designs. Their gentle, smiling faces are rectangular and elongated.

Lotus Ceiling with celestial deities (detail), Central Binyang Cave, Northern Wei Dynasty, First Quarter of the 6th Century (photo: A1AA1A, CC0 1.0)

Low relief carving covers the lateral walls, ceiling, and floor. Finely chiseled haloes back the images. The halo of the main Buddha extends up to merge with a lotus carving in the middle of the ceiling, where celestial deities appear to flutter down from the heavens with their scarves trailing. In contrast to the Northern Wei style seen on the pentad, the sinuous and dynamic surface decoration displays Chinese style. The Northern Wei craftsmen were able to marry two different aesthetics in one cave temple.

Two relief carvings of imperial processions (below) once flanked the doorway of the cave entrance. The emperor’s procession is at the Metropolitan Museum, while the empress’s procession is at the Nelson-Atkins Museum. These reliefs most likely commemorate historic events. According to records, the Empress Dowager visited the caves in 517 C.E., while the Emperor was present for consecration of the Central Binyang in 523 C.E.

Emperor Xiaowen and His Court, c. 522–23, China, Northern Wei dynasty, limestone with traces of pigment, 82″ x 12′ 11″ / 208.3 x 393.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Offering Procession of the Empress as Donor with Her Court, c. 522 C.E., fine, dark-gray limestone, 80″ x 9′ 1 1/2″ / 203.2 x 278.13 cm (Nelson Atkins Museum)

These reliefs are the most tangible evidence that the Northern Wei craftsmen masterfully adopted the Chinese aesthetic. The style of the reliefs may be inspired by secular painting, since the figures all appear very gracious and solemn. They are clad in Chinese court robes and look genuinely Chinese—mission accomplished for the Northern Wei!

Tang Dynasty

The Tang dynasty (618–907 C.E.) is considered the age of “international Buddhism.” Many Chinese, Indian, Central Asian and East Asian monks traveled throughout Asia. The centers of Buddhism in China were invigorated by these travels, and important developments in Buddhist thought and practice originated in China at this time.

Fengxian Temple

This imposing group of nine monumental images carved into the hard, gray limestone of Fengxian Temple at Longmen is a spectacular display of innovative style and iconography. Sponsored by the Emperor Gaozong and his wife, the future Empress Wu, the high relief sculptures are widely spaced in a semi-circle.

Central Vairocana Buddha surrounded on either side by a monk, bodhisattva, heavenly king, a Vajrapani (thunderbolt holder), 673–75 C.E., Tang dynasty, limestone, Luoyang, Henan province, (photo: Kevin Poh, CC BY 2.0)

The central Vairocana Buddha (more than 55 feet high including its pedestal) is flanked on either side by a bodhisattva, a heavenly king, and a thunderbolt holder (vajrapani). Vairocana represents the primordial Buddha who generates and presides over all the Buddhas of the infinite universes that form Buddhist cosmology. This idea—of the power of one supreme deity over all the others—resonated in the vast Tang Empire which was dominated by the Emperor at its summit and supported by his subordinate officials. These monumental sculptures intentionally mirrored the political situation. The dignity and imposing presence of Buddha and the sumptuous appearance of his attendant bodhisattvas is significant in this context.

Vairocana Buddha, monks and bodhisattvas, 673–75 C.E., Tang dynasty, limestone, Luoyang, Henan province, (photo: Sanjay P. K., CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The Buddha, monks and bodhisattvas (above) display new softer and rounder modeling and serene facial expressions. In contrast, the heavenly guardians and the vajrapani are more engaging and animated. Notice the realistic musculature of the heavenly guardians and the forceful poses of the vajrapani (below).

Vaiśravana, one of The Four Heavenly Kings, is on the left (indicated by the stupa in his right hand). Vajrapāṇi (on the right) are spiritual beings that wield the thunderbolt, 673–75 C.E., Tang dynasty, limestone, Luoyang, Henan province (photo: Dominik Tefert, public domain)

Arhats, Kanjing Temple, Longmen Caves, Luoyang, China (photo: G41rn8, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Kanjing Temple

Arhats (detail), Kanjing Temple, Longmen Caves, Luoyang, China (photo: Gary Todd, CC0 1.0)

Tang dynasty realism—whether fleshy or wizened, dignified or light-hearted—is displayed in the Kanjing cave Temple at Longmen. Here we see accurate portrayals of individuals. This temple was created from about 690–704 C.E. under the patronage of Empress Wu.

In the images of arhats (worthy monks who have advanced very far in their quest of Enlightenment), who line the walls, the carver sought to create intense realism. Although they are still mortal, arhats are capable of extraordinary deeds both physical and spiritual (they can move at free will through space, can understand the thoughts in people’s minds, and hear the voices of far away speakers). Twenty-nine monks form a procession around the cave perimeter, linking the subject matter to the rising interest in Chan Buddhism (the Meditation School) fostered at court by the empress herself. These portraits record the lineage of the great patriarchs who transmitted the Buddhist doctrine.

Sovereignty and iconography

Foreign rulers of the Northern Wei, yearning for assimilation and control, made use of Buddhist images for authority and power. Tang dynasty leaders thrived during China’s golden age, asserting their sovereignty with the assistance of Buddhist iconography. Today you can visit the stunning limestone remains in Luoyang, New York City, and Kansas City.

The author would like to thank her teacher, Professor Angela Howard.