View from the cloister of Santa María of Pedralbes, founded 1326, Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain (photo: julie corsi, CC BY 2.0)

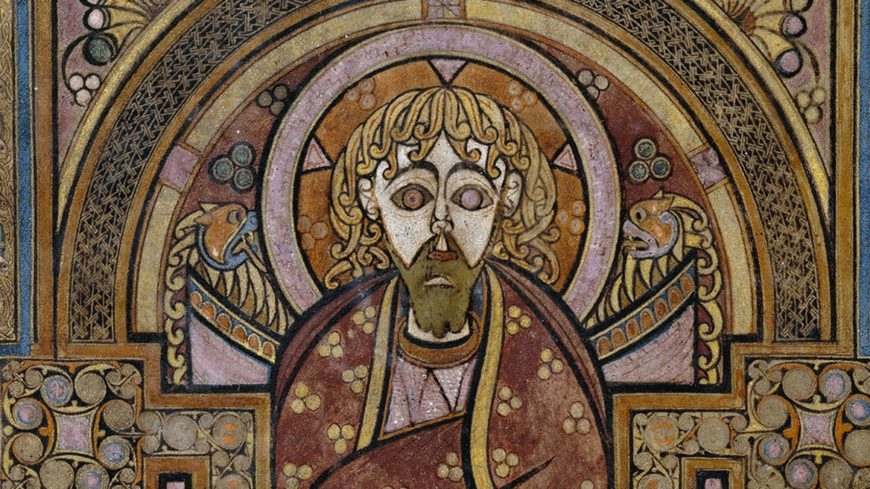

In the hubbub of Barcelona, just outside the city center, the delightful late Gothic monastery (or monestir in Catalan) of Santa María of Pedralbes offers a cool, calm respite—especially in the summer. While the overall space itself is impressive, one of the most spectacular is a chapel filled with brilliantly colored frescoes that present narrative scenes from the life of Jesus and Mary, accompanied by saints and angels. The murals demonstrate Bassa’s engagement and adaptation of Tuscan artists like Giotto and Simone Martini, and so speak to the dynamic networks of cultural exchange happening throughout the Mediterranean at the time.

Why are these murals here and who paid for them?

Elisenda de Moncada i de Pinós, Queen of Aragon between 1322 and 1327, established the Franciscan nunnery for Poor Clares at Pedralbes in 1326. Both Queen Elisonda and King Jaume II were important patrons of art and architecture. After King Jaume II’s death, Elisonda dressed in the Clarissan habit but took no official vows, and lived near Pedralbes in a new palace. Like other queens on the Iberian Peninsula, Elisonda had vast funds at her disposal (the result of matrimonial law). Her mother came from the wealthy Pinos family, while her father was an important administrator of the area who had worked under Jaume II. When she died, she was buried at Pedralbes, and her tomb is adorned with an effigy sculpture of her. She left her remaining matrimonial wealth to the nuns.

Ferrer Bassa, frescoes of the Chapel of Saint Michael, Santa María of Pedralbes, Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain, 1343/1346–1348 (public domain)

At one point, the monastery of Pedralbes had many murals animating its interior after its construction. Unfortunately, many of them have suffered the ravages of time and are now faded, fragmentary, or destroyed. The chapel of Saint Michael is an exception. Its murals remain largely intact, testifying to the former glory of the other murals in the monastery’s space. They were created by the Catalan artist, Ferrer Bassa. He was hired in 1343 by Francesca de Saportella i de Pinos, the abbess of the monastery, who also happened to be the queen’s niece, to produce the chapel’s murals. At some point he stopped working, but picked up the work again in March 1346. [1]

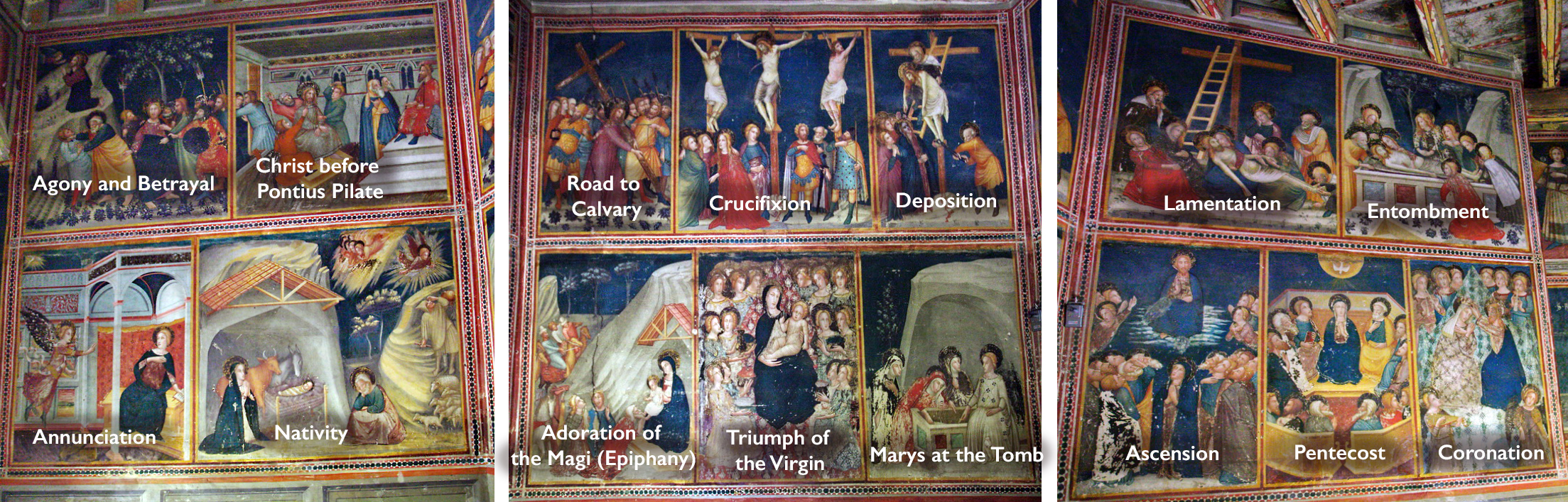

The contracts detail what Bassa was supposed to include in the murals. One explicitly details the chapel’s iconography, as well as materials.

It is agreed between the lady abbess of Pedralbes and Ferrer Bassa that the said Ferrer shall paint in fine colours, with oil, the Chapel of St. Michael, which belongs to the lady abbess, and here portray the Seven Joys of Mary, Mother of Jesus, amply and with all the figures that are necessary. He will also portray Seven Stories of the Passion of Jesus Christ. . . . The first, when Jesus was arrested; the second, when he was judged before Pilate, veiled, scourged and taunted; the third, when he was nailed to the cross; the fourth, when he died on the cross, with the two thieves, Mary and the other Marys, John, and the centurion with the other Jews; the fifth, when he was brought down from the cross; the sixth, when he was laid in the Monument; the seventh, the lamentation with Mary and John.

St. Michael, St. John the Baptist, St. James, St. Francis, St. Mary(sic) Clare, St. Eulalia, St. Catherine and the deacon St. Antoninus of Pamiers must also appear. Also a Majesty with two angels over the door, inside the chapel. And all the images must have diadems and embellishments in fine gold.

And beneath the aforesaid stories and images, there will be curtains by way of drapery on the walls. [2]

The contract indicates that the abbess of Pedralbes played an important role in determining the materials Bassa should use and what should be depicted on the chapel’s walls. Saportella’s desire for Bassa to “paint in fine colours, with oil” indicates that she wanted a high-quality mural painting. In reality, however, the mural is a mixture of techniques (oil, fresco secco, and buon fresco).

The life of Mary and Jesus

Ferrer Bassa, frescoes of the Chapel of Saint Michael, Santa María of Pedralbes, Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain, 1343/1346–1348 (public domain)

But do the stipulations of the contract match what we see in the chapel? Indeed, Bassa did paint the scenes requested from the life of Mary and Jesus.

Ferrer Bassa, Pietà, fresco, Chapel of Saint Michael, Santa María of Pedralbes, Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain, 1343/1346–1348

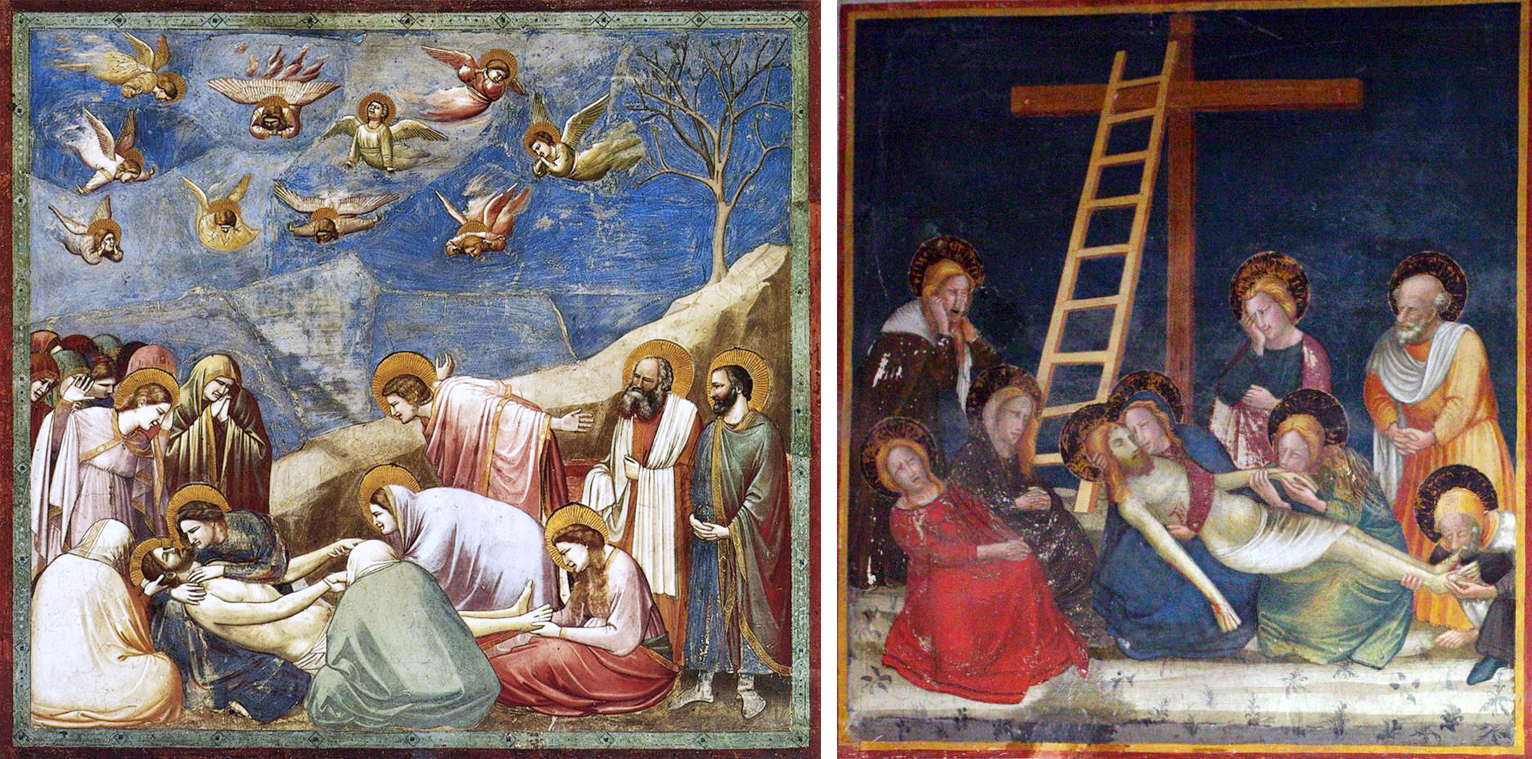

In each scene, Bassa varied the poses of his figures and their expressions to add drama and emotion. In the Pietà, at the base of the cross, Mary stoops to cradle Jesus’ face, touching her cheek to his. Mary Magdalen kisses Christ’s bloodied hand. Saint John raises his right hand to his teary face as he looks down at Christ. Others in the scene wring their hands, turn away in sadness, or tear at their hair. All the figures are positioned around the diagonal, prone body of the deceased Jesus. Bassa modeled all the figures with light and shadow to create convincing three-dimensional bodies, and they appear to have weight and stand or sit firmly on the ground. Bassa also attempted to show convincing human anatomy (look, for example, at Christ’s chest and abdomen), adding to his figures’ naturalism and increasing the emotional resonances of the unfolding narratives.

The figures appear crowded, and the compressed composition adds to the drama by focusing on the essential figures and elements. There is no deep recession into space. Instead, Bassa placed all the figures in the foreground, and the bodies overlap to suggest spatial depth. There are few extraneous motifs. The landscape is indicated by scattered plants in the immediate foreground, a rocky outcropping on which the drama unfolds, and a darkened background. It appears more like a stage setting than Golgotha (the hill atop which Jesus was crucified).

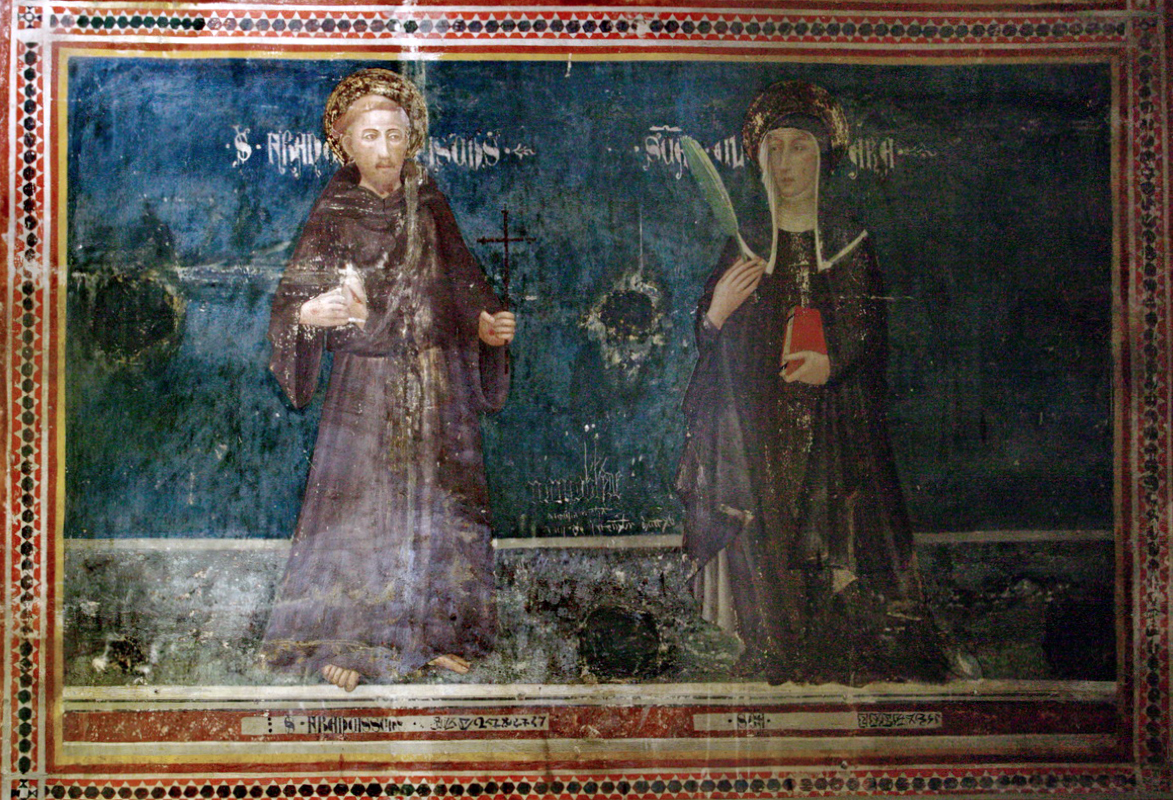

Ferrer Bassa, Saint Francis and Saint Clare, fresco, Chapel of Saint Michael, Santa María of Pedralbes, Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain, 1343/1346–1348 (public domain)

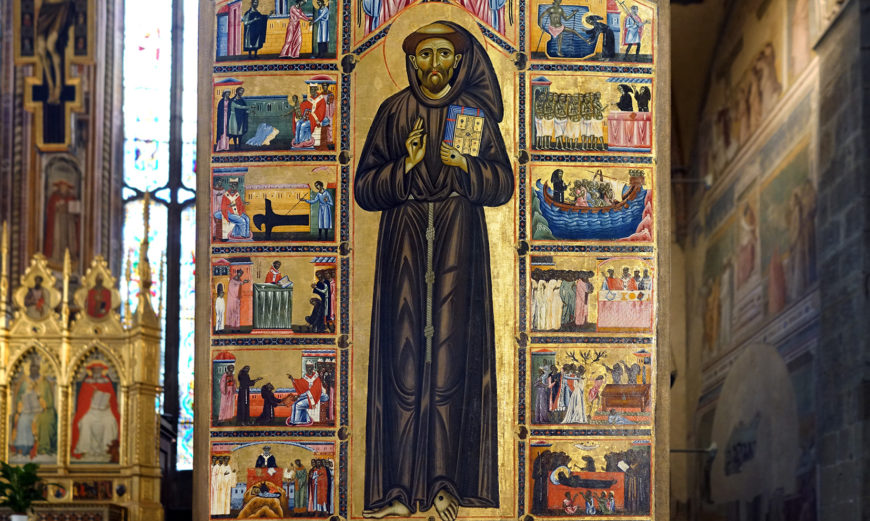

Besides the narrative scenes revolving around Jesus and Mary, we see a variety of standing saints and angels. To the right of the Triumph of the Virgin, Saint Francis and Saint Clare stand in their coarse-hair habits, which Franciscan monks and nuns wore as a sign of their vow of poverty. Their presence in the chapel makes sense, because after all this was a space for Franciscan nuns. Saint Francis founded the religious order in 1209, and Clare was the first female Franciscan nun. Franciscans arrived early on the Iberian Peninsula, and Franciscanism spread rapidly throughout the peninsula in the thirteenth century.

Ferrer Bassa, saints, fresco, Chapel of Saint Michael, Santa María of Pedralbes, Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain, 1343/1346–1348 (public domain)

Ferrer Bassa, St. Barbara, fresco, Chapel of Saint Michael, Santa María of Pedralbes, Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain, 1343/1346–1348 (public domain)

Many other saints stand with their respective attributes on the walls, such as Saint Barbara who holds a tower. She was an early Christian martyr who lived as a chaste virgin (which would have appealed to nuns who had taken similar vows). Barbara was locked in a tower by her father to protect her, but he ultimately killed her for practicing Christianity. The inclusion of saints like Barbara also undoubtedly reflects the increasing popularity of stories about the lives and miracles of saints, most famously collected in the Golden Legend (compiled around 1260 by Jacobus de Voragine).

Bassa’s figures resonate with a heightened emotionality, a choice that was likely due to the influence of Franciscanism. The Franciscans, more so than other religious orders, wanted people to identify with Jesus’ and Mary’s humanity by encouraging Christian devotees to appeal to their emotions. The Franciscan Pseudo-Bonaventure’s Meditations on the Life of Christ encapsulates this new approach to religious experiences, asking readers to visualize Christ’s life as if they were there, and to engage in a more physical type of prayer involving kneeling, praying, crying, reading, looking, and touching.

A Catalan artist in a global era

Bassa’s frescoes share a number of similarities with late Gothic Tuscan artists in Italy. Giotto’s earlier fourteenth-century Scrovegni chapel presents a similar narrative cycle to Bassa’s chapel, albeit on a larger scale for the wealthy patron who commissioned it. We see scenes from the life of the Virgin and Jesus, divided into narrative vignettes. Giotto’s figures are also modeled with light and shadow, and their expressions and poses add emotion and drama to his scenes as well. Bassa’s perspectival systems and figures like his kneeling angels look similar to paintings by Sienese painters, such as Simone Martini, Duccio di Buoninsegna, and Pietro Lorenzetti. Simone’s kneeling angels in his Maestà look similar to Bassa’s, and Lorenzetti’s Crucifixion in S. Francesco in Siena also provides a parallel to Bassa’s Chapel of St. Michael.

Left: Simone Martini, Maestà, fresco, Palazzo Pubblico, Siena, Italy, 1315–1321; right: Ferrer Bassa, Maestà, fresco, Chapel of Saint Michael, Santa María of Pedralbes, Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain, 1343/134–1348

But what do these similarities mean? What do they tell us?

The Iberian Peninsula was a dynamic place in the fourteenth century, with artists from what is today France and Italy arriving in the area, as well as Catalan artists traveling elsewhere. The Kingdom of Aragon (especially in the areas of Barcelona and Valencia), had early connections with Italy, which might explain the desire for Italianate influences at Pedralbes. Still, the circumstances under which Bassa would have encountered Giotto’s Arena Chapel or Sienese paintings remains unclear.

Left: Giotto, Pietà, fresco, Scrovegni Chapel, Padua, Italy, c. 1305; Right: Ferrer Bassa, Pietà, fresco, Chapel of Saint Michael, Santa María of Pedralbes, Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain, 1343/1346–1348

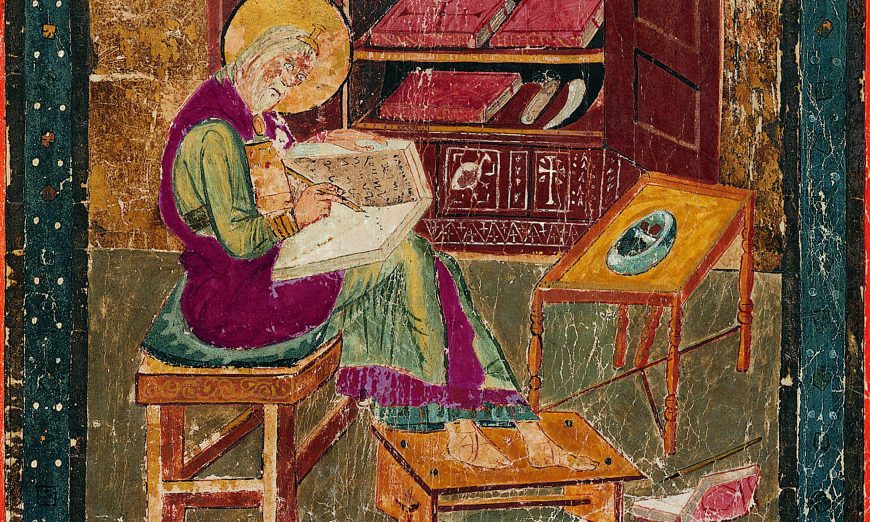

Some scholars feel that he must have traveled to the Italian Peninsula to see them first hand. Even if this were the case, we still have more questions: did he simply recall these artworks from memory? Did he carry a sketchbook? Simone Martini also worked at the papal court at Avignon (in southern France), so perhaps Bassa viewed the Sienese artist’s frescoes there. Other documentary evidence indicates that King Peter IV of Aragon (known as “the Ceremonious”) commissioned Bassa to create an altarpiece for the Ciutat of Mallorca in the mid-fourteenth century. [3] The Kingdom of Mallorca had connections to Italy, and this is especially clear in some of the art that remains from this time like altarpieces as well as illuminated manuscripts. We know of several Italian artists who worked on the island, including the Sienese stained-glass maker Matteo di Giovanni. Perhaps Bassa studied artworks found on the island? No matter the circumstances, Bassa’s adaptation and selective borrowing from Tuscan artists more generally suggests an inventive artist who combined different ideas and practices that he came into contact with during his life.

Ferrer Bassa

Bassa is known to have illuminated manuscripts, and painted altarpieces and frescoes. He worked for kings, queens, and nobles. In Barcelona, he had a thriving workshop. He likely died after contracting the bubonic plague (also known as the Black Death) that broke out in 1348, and which killed about 40–60% of the population in Europe.

Circle of Ferrer Bassa, Virgin and Child, with the Crucifixion and the Annunciation, and the Coronation of the Virgin and the Presentation in the Temple, c. 1340–48, tempera and gold leaf on panel, 127.6 x 184 x 4 cm (The Walters Art Museum)

While the murals of the Chapel of St. Michael have documentation, most of Bassa’s works do not. Some of the works currently attributed to Ferrer Bassa could possibly be those of his son, Arnau Bassa, because the two collaborated. The legacy of Ferrer Bassa’s Italianate adaptations lived on among other artists associated with his workshop, including his son. Even though most of the murals at Pedralbes have not survived well, we are fortunate to have his murals in the monastery because they powerfully demonstrate the ongoing, dynamic processes of cultural and visual exchange occurring on the Iberian Peninsula.