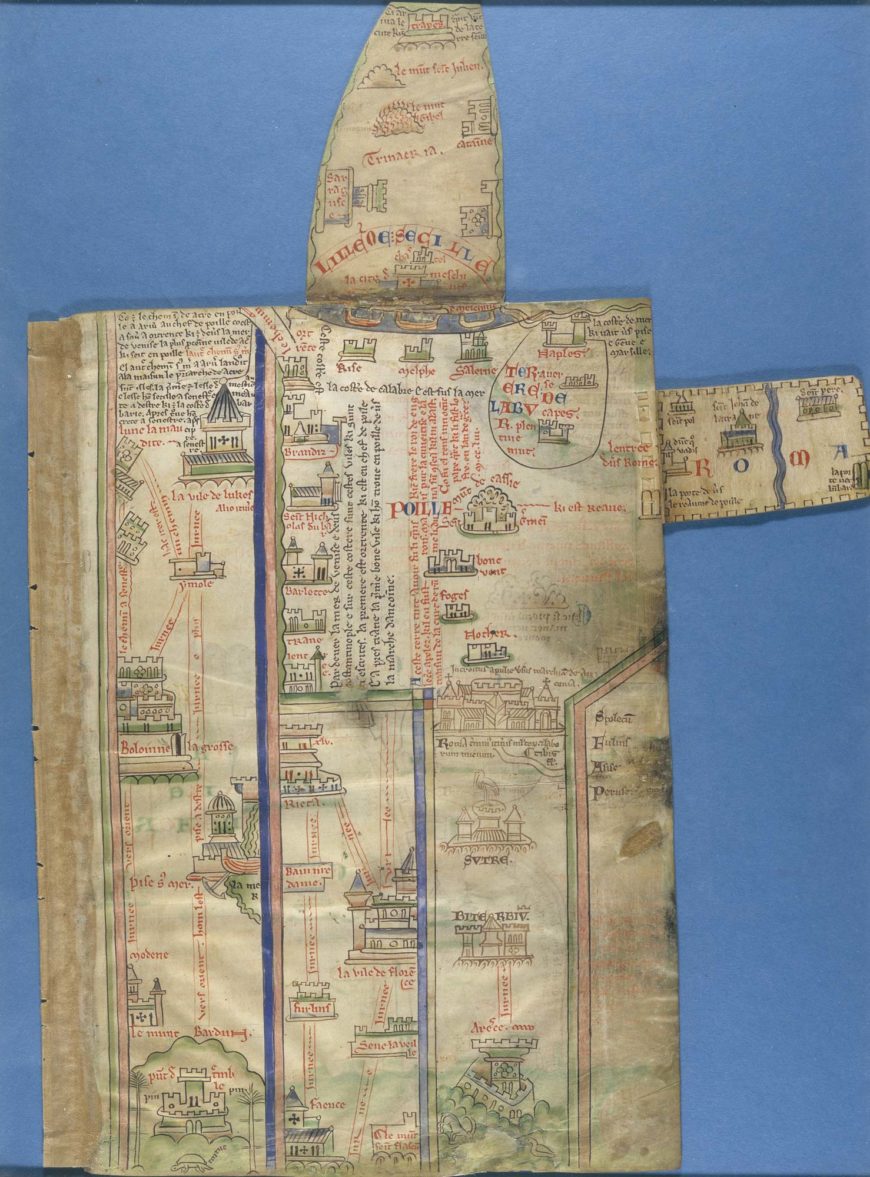

Matthew Paris’s itinerary maps from London to Palestine. Despite having never been to Palestine, the monk and historian Matthew Paris (c. 1200–1260), created an itinerary from London to Palestine.

This map of Palestine from the Royal manuscripts collection was created by Matthew Paris in mid-13th-century, and is dominated by its plan of Acre – the large walled enclosure with a camel outside it. Jerusalem, another walled enclosure (top right) is small by comparison, and other coastal cities (centre right) are marked simply by castles and towers. It is not known where Matthew Paris got his information about Acre, which a Latin note on the map as ‘the hope and refuge of all Christians in the Holy Land’ – it was the last surviving foothold of the crusaders there.

Who was Matthew Paris?

Matthew Paris (c. 1200–1260) was a medieval monk and chronicler. He entered the Abbey of St Alban as a monk on 12 January 1217. Matthew spent the rest of his life there, apart from visits to the royal court in London, and a year-long mission that took him to an abbey in Norway. Through the maps that he created, however, he travelled the world. His works includes several maps of Great Britain, a world map and maps of Palestine. All are marked by his intense curiosity about the outside world; he experiments with different renderings of Great Britain and of Palestine as if trying to work out his own ideas of what they were really like.

Matthew Paris produced the most important historical writings of the 13th century. His chief work, the Chronica Major, chronicled events from the creation of the world until 1259, the year he died. For its greater part, the Chronica Major is a revision and expansion of an existing chronicle by an earlier St Alban’s monk, called Roger of Wendover. From 1235 onwards, however, it’s the first-hand record of events the author heard about (perhaps from northbound travellers, who would stay at St Alban’s on their first night out of London) or witnessed for himself.

Why are his manuscripts important?

Paris is one of the most engaging of medieval chroniclers. His accounts are detailed and well informed, with lively descriptions of people involved and analysis of the causes and significance of the events recorded. Matthew’s connections made him a well-placed observer of contemporary affairs. He was on personal terms both with the king, Henry III, and his influential brother, Richard, Earl of Cornwall. At their courts Paris must have gained many insights into domestic and foreign politics.

His writings reveal a man of strong opinions who was not afraid to speak his mind. Being befriended and publicly honoured by Henry III on several occasions did not prevent him from being as critical of the king’s lack of prudence in political matters as he was praising of his piety in religion.

What do these maps show?

His itineraries of routes from London to Palestine, of which the first image digitised here is perhaps the most splendid example, accompanied his chronicle of world history. They represented a spiritual rather than a physical journey. Each place on the journey probably had its allegorical counterpart within the cloisters and church of St Albans Abbey (rather like the Stations of the Cross in modern Catholic churches) and the monks would follow the route as a type of spiritual exercise.

The routes themselves, however, are firmly embedded in reality and practicality. Important geographical features, such as rivers, hills and important buildings, are noted, and attractive alternative routes are shown along the way. These are particularly typical of Matthew and would have made him a marvellous tour guide had he been alive today.

In the style of modern digital route planners, the routes are shown as straight lines, with all extraneous information, which the pilgrim could not have seen from the road, omitted. Indeed Matthew probably drew these maps on the basis of written itineraries consisting of lists of place names. Yet he adorns his versions with picturesque town symbols and quite often with additional decoration, such as palm trees or even – once arrived in Palestine – with camels and other exotic animals.

This second map featured here (digitised image 6, ff. 4v–5r) illustrates the end of the journey, with Jerusalem surrounded by a crenellated wall labelled ‘civitas Ierusalem’ (Jerusalem city). Paris has included within the city three important sites: on the left, a domed structure for the Dome of the Rock, transformed by the Crusaders into the Templum Domini (the temple of the Lord), as it is labelled (although it had already been retaken by the Saracens when this map was made). In the right-hand corner is another mosque that had been turned into a church, the Temple of Solomon, a domed building given to the order of the Knights Templar, who took their name from this structure. The third building is the pilgrimage church of the Holy Sepulchre, represented by a circle in the lower corner.

What other maps did Matthew Paris produce?

Paris was an accomplished artist, providing many expert drawings in the margins of his manuscripts to illustrate the events he described. Among these are the first known views and plans of London. He also produced maps of Great Britain, intended as a complement to his shorter chronicle of English history, which are the earliest surviving maps with such a high level of detail. They stand out in the history of medieval map making as the first attempts to portray the actual physical appearance of the country rather than represent the relationship between places in simple schematic diagrams.

Article originally published by The British Library (CC BY-NC 4.0)