While one may be inclined to emphasize how “foreign” the medieval book is—they are, after all, made of dead cows, and are handwritten—they present such recognizably modern features as a justified text, footnotes, running titles and page numbers.

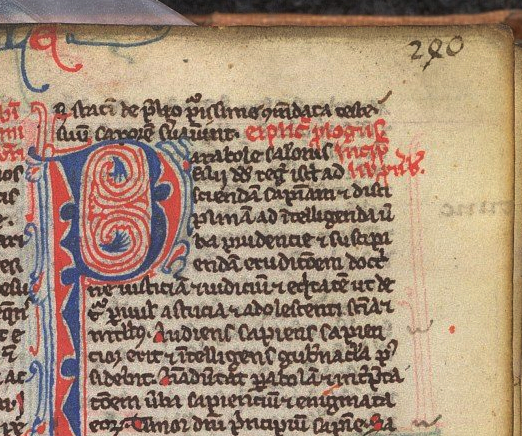

Leaf (page) number in Paris Bible, London, British Library, Arundel MS 311, fol. 240, 13th century

Visiting a bookseller

The similarities run much further than mere physical traits, however. Take for example the manner in which the book was made and acquired from the 13th century onwards. If you wanted a book in the later Middle Ages you went to a store, as in our modern day. However, the bookseller did not normally have any books in stock—except for perhaps some second-hand copies. You would tell him what you wanted, both content-wise and with respect to the object’s material features. You could specify, for example, that he use paper (instead of parchment), cursive script (and not book script) and add miniatures (or forego decoration). Just like so many other objects you bought in late-medieval society, the commercially-made manuscript was custom-tailored to the individual who purchased it.

The professionals who made books for profit were usually found near the biggest church in town. This was a well-chosen spot as canons and clerics (i.e. people who visited the church and who could read) formed an important part of the clientele. By the 14th century true communities of the book had formed in the neighborhoods around churches and cathedrals. Evidence from such cities as Antwerp, Bruges, Brussels, London and Paris suggests that in these communities a diverse group of artisans interacted with clients and with each other. It was a world bound not only by the book, however, but also by profit.

Marketing

Whether you were scribe, illuminator or binder, as a professional you would strive for quality and diversity as this ensured bread and butter on the table. In parallel to our modern book business, medieval manuscript artisans used various marketing strategies to attract new clientele. The most striking of these is advertisements. Scribes hung large sheets outside their doors to show what kind of scripts they had mastered. The short writing samples found on these sheets were often accompanied by the names of the scripts, which shows just how professional the world of the book had become. A particularly rich specimen survives from the shop of Herman Strepel, a professional scribe in Münster (c. 1447). In the true spirit of medieval marketing he wrote the names of all the scripts in golden letters on his advertisement sheet.

Advertisement sheet from Herman Strepel, professional scribe in Münster, The Hague, Royal Library, 76 D MS 45, c. 1447

Scribes also included advertisements in books they had copied for a client. An example of such “spam” is found in a French manuscript made in Paris by a scribe who calls himself Herneis. On the last page of the book he writes, “If someone else would like such a handsome book, come and look me up in Paris, across the Notre Dame cathedral.” Herneis and his fellow bookmen lived and worked in the Rue Neuve Notre Dame, which served as the center of commercially-made vernacular books. Similarly, students were served in the Rue St Jacques, on the Left Bank, where the latest Latin textbooks were on offer. For Parisians and students it was handy to have all the professionals in one street: you knew where to go when you needed a book and it was easy to check out who was available for making one for you.

Advertisement by Herneis le Romanceur, professional scribe in Paris. Giessen, Universitätsbibliothek, MS 945, 13th century

Book streets

This centralization was equally convenient, however, for the artisans themselves. Booksellers (also called stationers) in Rue Neuve Notre Dame and in other such “book streets” in European cities depended on the professional scribes, illuminators and binders that lived in their vicinity. They would hire them for various projects. When a client came to order a book from a stationer, the latter would divide the work among the artisans he usually worked with. One copied the text, another drew the images, and a third bound the book. These hired hands were given contracts which specified precisely what they would have to do and how much money they received for it. From time to time the stationer would come and check on the progress they made. In some manuscripts these cost estimates were scribbled in the margin. Although making books for profit was a common scenario in the later Middle Ages, it did not make you particularly rich. On the last page of a Middle Dutch chronicle a clearly frustrated scribe wrote, “For so little money I never want to produce a book ever again!”

Marginal note in pencil regarding payment to the professional scribe Jehan de Sanlis, “ci (com)me(n)ce Jeha(n) de Sanlis a ratable VI d. a la piece” (Jehan de Sanlis made this for 6 pence per quire), The Hague, Royal Library, MS 71 A 24, 13th century

The printing press and the demise of the manuscript

The world of professional medieval scribes was shaken up by the coming of Gutenberg’s printing press around the middle of the 15th century. The ink pots dried up and the handwritten book slowly turned into an archaic object that was more costly than its printed counterpart. In the 16th century only large choir books (which did not fit on the press) and handsome presentation copies, custom-made for an affluent client, were still written by hand.

And so we see scribes jumping the handwritten ship, many ending up working in printing shops. Here, too, a striking parallel between the medieval and modern world of the book may be pointed out. Medieval producers and salesmen of books had to adapt to the new medium made popular by Johannes Gutenberg, just as publishers today have to change their ways in a world where pixels are gaining ground over ink.