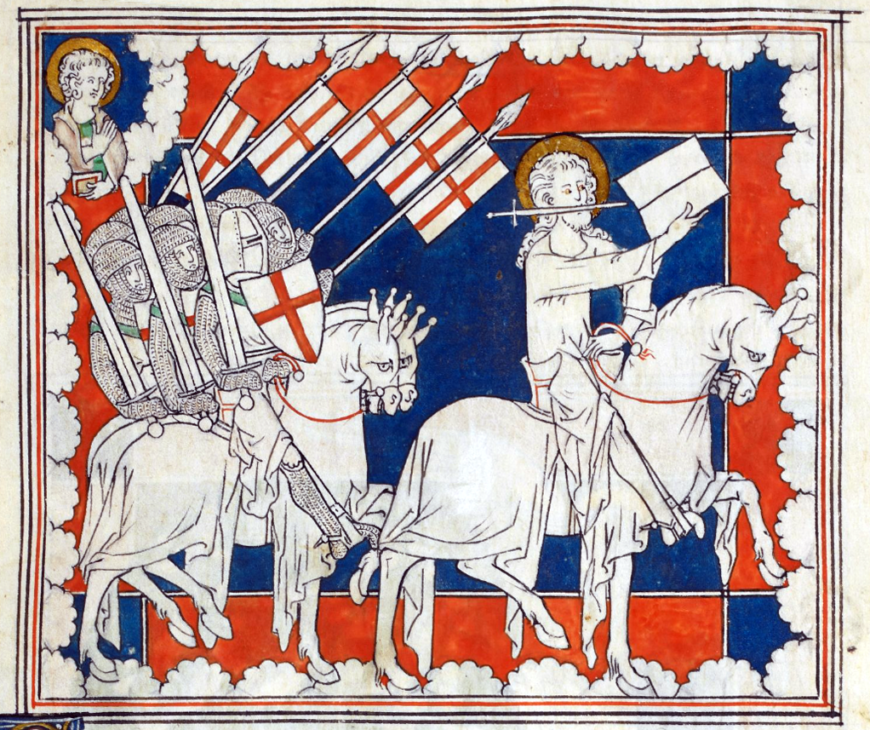

Christ leading crusaders into battle, detail from an Apocalypse, with commentary (The “Queen Mary Apocalypse”), early 14th century, f. 37 (British Library)

Just warfare

Crusades were wars—that is firm ground. More specifically, crusading was represented as just warfare, according to the idea of just war established by St. Augustine of Hippo.

Augustine wrote that warfare was sometimes a necessary and lesser evil in certain conditions. Specifically, a war could be just if there was:

a) just cause,

b) legitimate authority, and

c) right intention.

A just cause was a previous injury or act of aggression. As a result, crusading was described as defensive.

A legitimate authority was just that: an authority who held the power—granted by God, from Augustine’s perspective—to invoke war. Crusading, it was argued, was authorized by popes and legitimate secular leaders.

Participants had the right intention if they believed war was completely unavoidable and sought only to use minimal force to check aggression against them. In theological terms, participants were supposed to be motivated by Christian love, (i.e. charity), rather than by anger, hatred, or fear. Crusade supporters stressed that participants were driven by the desire to help liberate purportedly oppressed Christians and save them from purported atrocities and slavery, and the desire to do the same for the personified Church or even Christ himself, both supposedly injured by the enemies of the crusaders.

But participating in a just war could still be sinful. For example, Duke William I of Normandy’s invasion of England was considered just, but Norman participants had to do penance afterwards. So saying that crusading was a just war wasn’t enough. Many writers communicated that crusading was holy warfare, meaning that it was a just war that was not only authorized but also realized by God himself. In theological terms, then, God was the one taking action; God was the one waging war. Crusaders were divine tools, rather than moral agents in their own right. It was this belief that led one monk, Guibert of Nogent, to title his account of the First Crusade “The Deeds of God done through the Franks” (he was not-so-subtly revising an earlier, and in his opinion theologically crude account, titled “The Deeds of the Franks”). Of course, if a crusade was a holy war, then the enemies of crusading were enemies of God and the whole Christian faith, not just enemies of particular Christians—and that was precisely how Muslims and other crusader targets were depicted in many pro-crusade accounts.

Crusader icon with St. Sergius carrying a crusader standard featuring a red cross on a white ground, with a female door, 13th century, from the Monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai, Egypt (photo: published through the Courtesy of the Michigan-Princeton-Alexandria Expeditions to the Monastery of St. Catherine on Mount Sinai)

Penitential warfare

Finally, crusading was also represented as penitential warfare. This means that crusading was believed to be an act of penance—a way to make amends to God for sins one had committed, so that an individual could achieve salvation. It means that crusading was not simply seen as a necessary evil—it was seen as a positive spiritual good for those who participated. Participants were not merely excused for their involvement; they actively acquired spiritual merit. In the simplest terms, crusading was presented as a good deed, even though it involved killing people.

To make sense of this, we need to recognize that violence was often perceived to be much more morally neutral in medieval Europe than it is today. Violence acquired its moral value from intentions and context, like who was performing the violence and to whom it was done (this should remind you of Augustine’s just war theory: cause, authority, and intentions). Thus, the same action—let’s say, hitting someone in the face—could be immoral and unchristian in one context, and moral and Christian in another.

Given the penitential element in crusading and the number of expeditions that involved long journeys to holy places, it is not surprising that crusading was often described as a pilgrimage, a journey to a holy location like a shrine, a church, or even an entire city, like Jerusalem. Those who went on pilgrimage frequently sought spiritual advantages, like forgiveness of sins or a closer relationship with God or a saint; they also sometimes hoped for more earthly advantages, like healing. Pilgrimage was a sacred act for medieval Christians, and was itself often an act of penance (sometimes voluntary, sometimes assigned by a priest in confession). Crusading borrowed some of the language, rituals, and symbols of pilgrimage, and shared its penitential nature.

Aquamanile in the Form of a Mounted Knight, c. 1250, copper alloy, 37.3 x 32.7 x 14.3 cm, Germany (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Changing definitions

It’s important to emphasize again that people didn’t write a theory of crusading in advance. There wasn’t even a specific word for “crusade” until more than 100 years after the First Crusade. In addition, the nature of crusading seems to have operated differently and meant different things depending on time, place, and participants.

Additional resources

The when, where and who (of crusading).

Dr. Susanna A. Throop, The Crusades: An Epitome (Leeds: Kismet Press, 2018), an open access book.

Dr. Ariel Fein, “Material culture of the Crusades,” Reframing Art History, 2022.

The Crusades on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.