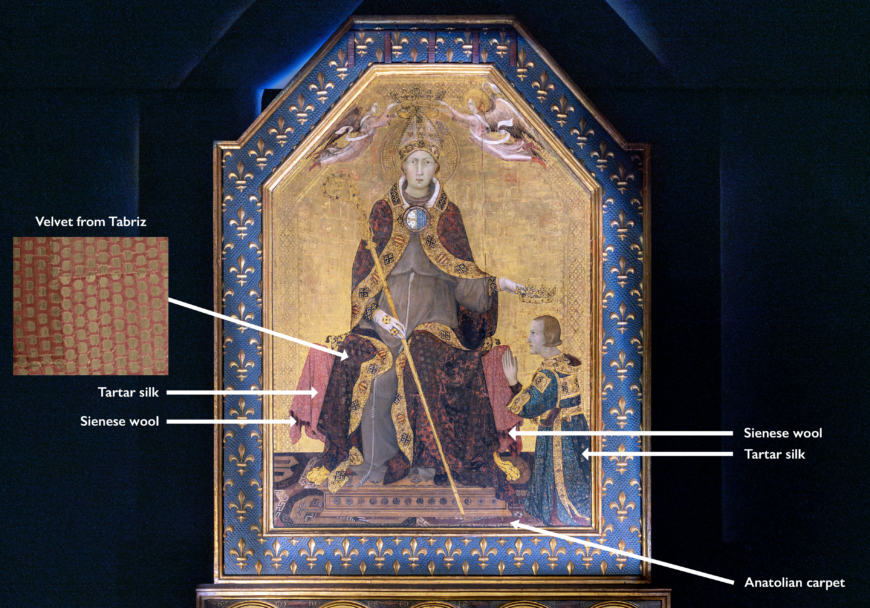

Simone Martini, Saint Louis of Toulouse, c. 1317, tempera, gold, and gems (lost) on panel, 121.6 x 74.2 inches (Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The youthful and determined gaze of Saint Louis of Toulouse, a famous Franciscan saint, stares out from the shimmering gold background of a ten-foot tall altarpiece by Simone Martini. The painting is the most famous work surviving from the vibrant Angevin court of Naples and is currently located in the city’s Museo di Capodimonte. This royal panel preserves a fascinating history of dynastic succession and a connected world in 14th-century Southern Italy.

A reluctant prince turned bishop

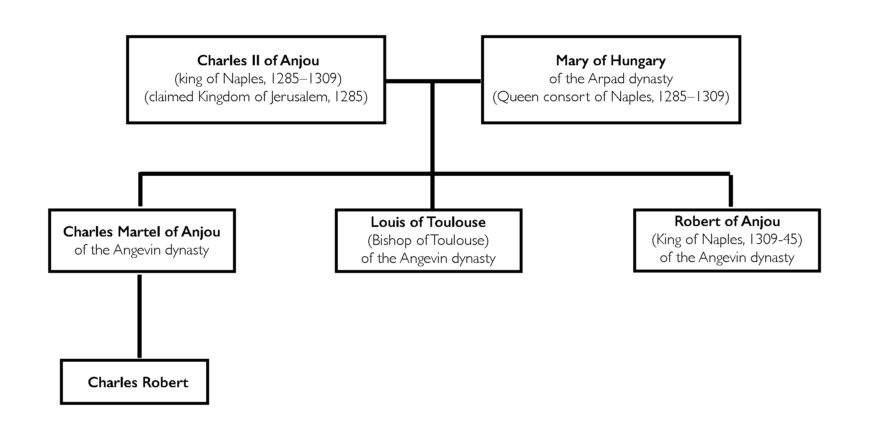

Louis was born a prince. He was the second son of Charles II of Anjou, the heir to the Kingdom of Naples. After his father became King in 1285, Louis and two of his brothers were held hostage under the Spanish King Ferdinand III of Aragon for seven years. While in captivity in Catalonia, the Angevin princes were tutored by Franciscans friars and Louis realized that it was his destiny to become a monk. This plan was derailed, however, when his older brother (Charles Martel) died unexpectedly and Louis found himself the next in line to inherit the throne of Naples (and become titular King of Jerusalem—a formal title without any real authority). Determined to live a spiritual rather than royal life, he negotiated with his father to become Bishop of Toulouse and elected to pass inheritance rights to his younger brother Robert.

The main panel of Simone Martini’s altarpiece depicts this story of succession. It shows a double coronation—two angels hold an ornate crown above Saint Louis’s head while Louis extends a nearly identical crown over the head of his brother, who kneels submissively to his right.

Saint Louis (detail), Simone Martini, Saint Louis of Toulouse, c. 1317, tempera, gold, and gems (lost) on panel, 121.6 x 74.2 inches (Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In the painting, Saint Louis wears a silvery miter. His heavily decorated gloves, cope, and crozier further indicate his status as Bishop of Toulouse. Under his magnificent church gear, he wears a far less luxurious garment: the rough wool habit of a Franciscan monk (worn by Franciscan monks and nuns as a sign of their vow of poverty). This detail demonstrates that Louis’s early ambition to join the order was successful. The young prince professed his Franciscan vows just a few days before he was ordained as Bishop of Toulouse in 1296. Although he went to France to assume official ecclesiastical duties, he ultimately chose to step down from his position after only six months and died on his return trip to Rome to resign before the Pope. Reports that his remains could perform miracles began to circulate almost immediately after his death, and his family campaigned heavily for his sainthood. He was canonized (officially recognized as a saint) in 1317 by Pope John XXII.

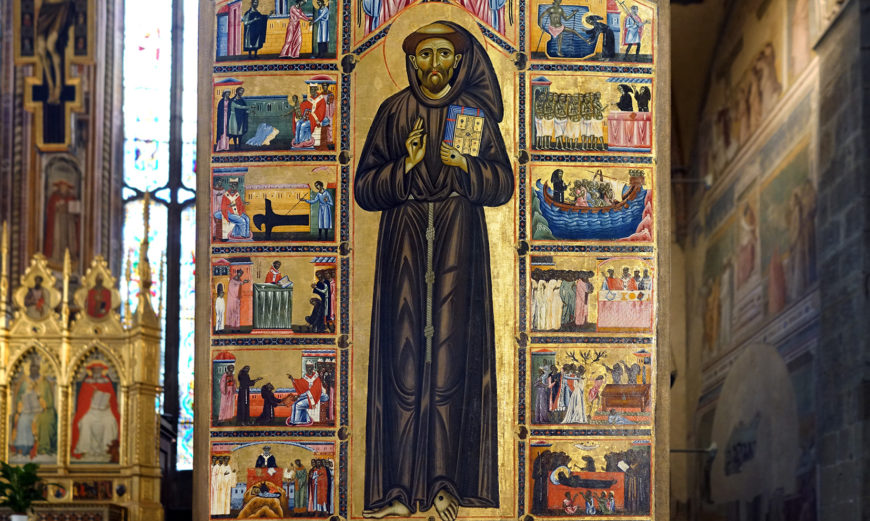

Saint Francis and scenes from his life, 1240s–1260s, panel (Bardi Chapel, Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

A Franciscan saint

The Franciscans were a popular mendicant order following the teachings of Saint Francis, the order’s founder. Francis inspired a large number of monastic houses across Europe and many works of art were made to commemorate his faith and miracles, such as the scenes we find in the Bardi Chapel in the Basilica of Santa Croce in Florence. Simone Martini’s painting of Saint Louis parallels early paintings of Saint Francis, depicting him specifically as a Franciscan saint. Positioned frontally and wearing a Franciscan habit, the Angevin prince’s waist is belted with a simple chord tied in three knots to symbolize his monastic vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience.

From left to right: 1. Meeting with Pope Boniface VIII; 2. Double scene of Louis’s ordination as Bishop of Toulouse and his profession of Franciscan vows; 3. Louis serves a meal to the poor at the Franciscan convent of Santa Maria in Aracoeli, Rome; 4. Louis’s funeral in Marseilles in 1297; 5. A posthumous miracle in which Louis revived a stillborn infant. Simone Martini, predella of Saint Louis of Toulouse, c. 1317, tempera, gold, and gems (lost) on panel, 121.6 x 74.2 inches (Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The similarities with Franciscan altarpieces do not end at Louis’s clothing. On the predella are episodes from Louis’s saintly life. Although paintings of Francis included anywhere from four to twenty apron scenes, Louis here only has five. They show (from left to right) his deal with the Pope to allow him entry into the Franciscan Order, his vow profession and ordination, an act of charity, his funeral in 1297, and a posthumous miracle in which he resurrected a stillborn infant. This small number of scenes indicates that he was probably a new saint when the panel was made. In fact, Simone Martini is often credited with inventing the iconography for the stories himself. This means the work was likely created around 1317 when Louis was canonized.

Fleur-de-lis (detail), Simone Martini, Saint Louis of Toulouse, c. 1317, tempera, gold, and gems (lost) on panel, 121.6 x 74.2 inches (Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Fleur-de-lis on the back (detail), Simone Martini, Saint Louis of Toulouse, c. 1317, tempera, gold, and gems (lost) on panel, 121.6 x 74.2 inches (Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples; photo: Claire Jensen)

Angevin heraldry

The exact circumstances of Simone Martini’s altarpiece creation are unknown, but it seems that it was paid for by Louis’s family. The frame, which is original to the work, serves as a monumental Angevin crest. Decorated with gilded plaster fleur-de-lis on a textured blue background, the frame perfectly reproduces the coat of arms of the French Kings who controlled Naples in the later Middle Ages. The blue and gold lily motif is found throughout the work: embroidered in crests on Louis and Robert’s clothing, delicately punched into the border of the gilded background, and even painted on the reverse side of the frame.

Morse in wood, glass and tempera paint (detail), Simone Martini, Saint Louis of Toulouse, c. 1317, tempera, gold, and gems (lost) on panel, 121.6 x 74.2 inches (Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples; photo: Claire Jensen)

The morse made out of painted wood and glass on Louis’s chest is an ingenious addition by Simone Martini. It resembles actual objects but it is also seen here as a political symbol.

Left: Morse in wood, glass and tempera paint (detail), Simone Martini, Saint Louis of Toulouse, c. 1317, tempera, gold, and gems (lost) on panel, 121.6 x 74.2 inches (Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: Morse with Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata, mid-14th century, made in Siena, Italy, gilded copper, translucent enamel, silver, parchment, glass gems, 12.9 x 12.9 x 4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Look closely and you’ll see the signature French lilies on the right and the cross of Jerusalem on the left—projecting Louis’s dual status as heir to the throne of Naples and titular King of Jerusalem in the later Middle Ages. The same divided crest appears on Robert’s blue robes, signaling that he inherited both titles when his brother renounced his right to rule.

Arpad family crest (detail), Simone Martini, Saint Louis of Toulouse, c. 1317, tempera, gold, and gems (lost) on panel, 121.6 x 74.2 inches (Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The gold border of Louis’s cope curiously includes another crest not represented on Robert’s vestments: the horizontal red and gold stripes of his mother Margaret’s Arpad family of Hungary. The omission of the Hungarian crest for Robert makes sense. When the third brother inherited the Kingdom of Naples, the title King of Jerusalem, and the Angevin holdings in France in 1309, he did not gain any of his mother’s territories. The Hungarian crown passed instead to his nephew, Charles Robert, the son of the original Angevin heir and Louis and Robert’s older brother, Charles Martel.

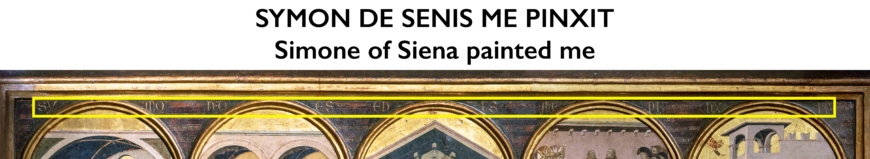

Simone’s signature (detail), Simone Martini, Saint Louis of Toulouse, c. 1317, tempera, gold, and gems (lost) on panel, 121.6 x 74.2 inches (Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

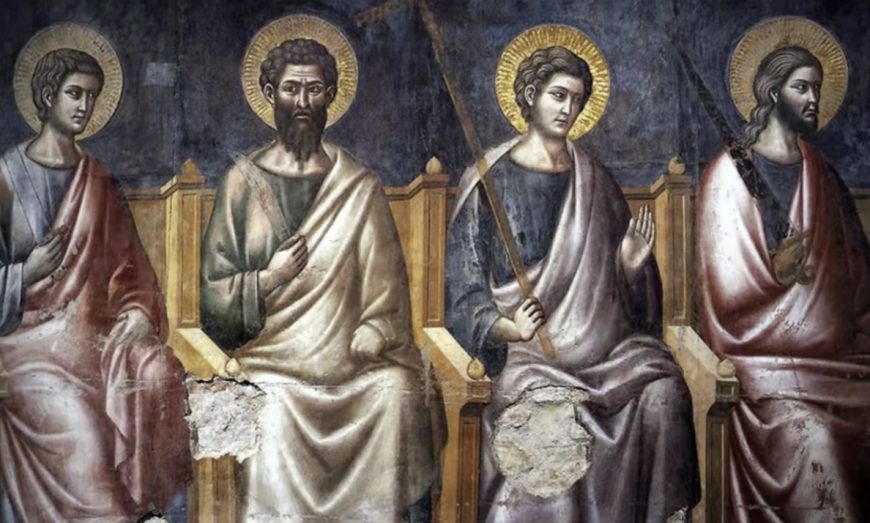

Simone Martini and international objects in Naples

Political alliances between Naples and Tuscany made it possible for one of the most famous artists from Siena to create the work. Although it was surely meant to be displayed in Naples, Simone Martini included his own origins in the composition. In the spandrels of the predella are divided letters that read, “SYMON DE SENIS ME PINXIT” (translation: Simone of Siena painted me). This sense of foreign presence was important for the Angevins because Naples was a wealthy center of global trade thanks to its Mediterranean coastal location. The royal family enhanced their capital’s cosmopolitan legacy by commissioning famous artists from elsewhere—like Simone Martini, Giotto, and Pietro Cavallini—to work for them. They also accumulated an impressive collection of objects from far-flung places, expressed by the decorative items we see in the Saint Louis painting.

Decorative items. Simone Martini, Saint Louis of Toulouse, c. 1317, tempera, gold, and gems (lost) on panel, 121.6 x 74.2 inches (Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0). The crimson velvet with gold octagons is 13th–14th century, Iranian, probably Tabriz, silk and metal thread (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Using his famous talent for capturing realistic detail, Simone Martini painted Louis’s cope as crimson velvet patterned with gold octagons from the Persian city of Tabriz. Draped over the lion-headed throne is another luxurious red cloth, one side in a red and black checked Sienese wool and the other in shiny Tartar silk imported from Mongol-held lands in Central Asia. Robert’s blue garment is also made of Tartar silk, an accurate choice given the Anjou family’s documented collection of Mongolian textiles. The floor is additionally covered by an Anatolian carpet, a knotted wool rug with geometric patterns from western Turkey. All of these international objects would have been available in the Mediterranean port city of Naples, making the painting an impressive record of Angevin wealth and mercantile connections.

Southern Italy and Robert of Anjou

In spite of its many innovations, the coronation subject is not unique. In fact, the closest art historical precedents are mosaics depicting the Norman Kings from the 11th and 12th centuries on the nearby island of Sicily. Perhaps the Angevins specifically chose this model to promote their power in a way that was recognizable in Southern Italy. They lost control of the island in a war known as the Sicilian Vespers in 1282 and subsequently made many failed attempts to regain it.

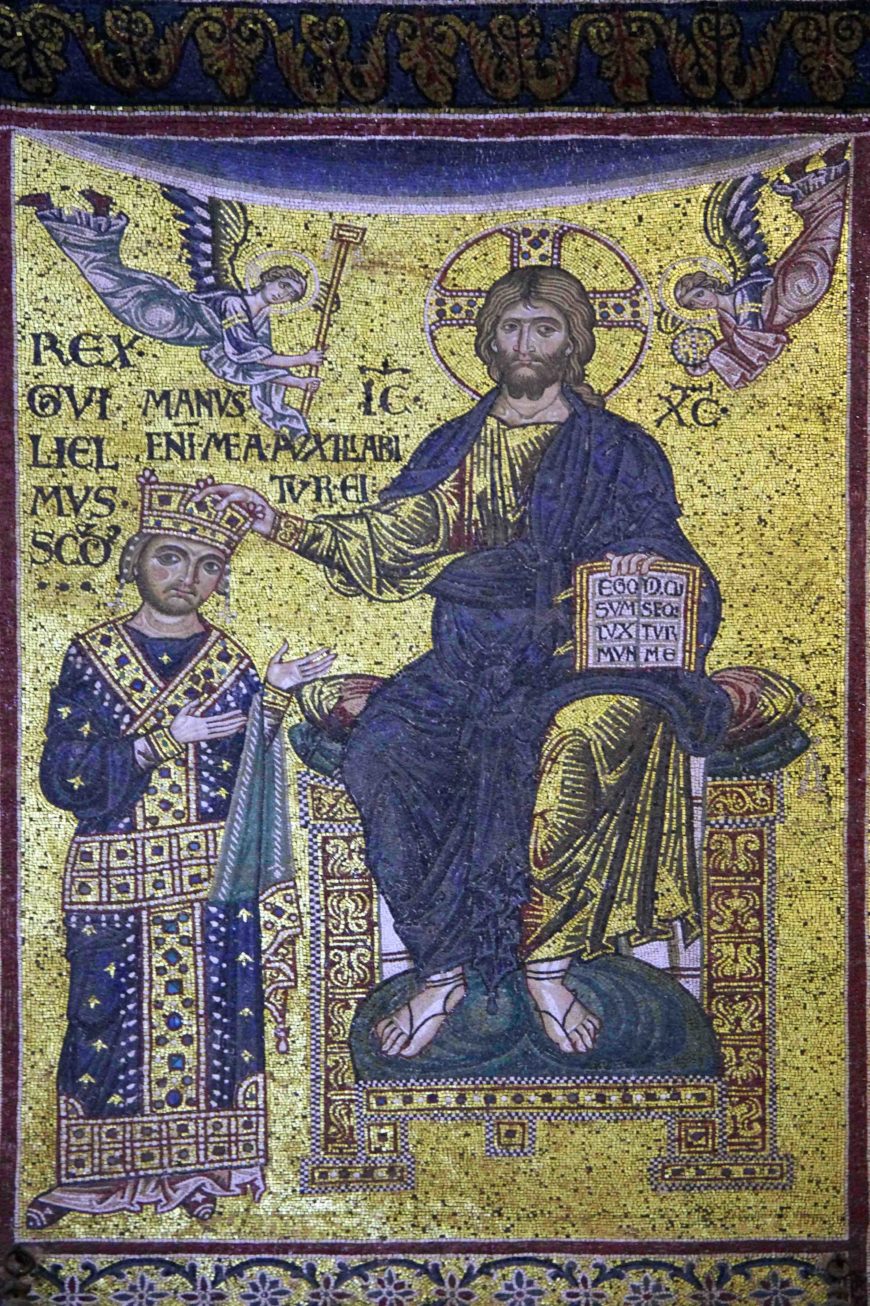

King William II crowned by Christ, c. 1180–90, mosaic on the north wall of sanctuary, Cathedral of Monreale, Sicily (photo: SNappa2006, CC BY 2.0)

By commissioning an altarpiece from Simone Martini that depicts a divine coronation on a gold background, the Angevin family projected a sense of historical continuity with their Norman predecessors in southern Italy. In a mosaic in the Cathedral of Monreale (Sicily), Christ is enthroned like Louis and places a crown on the head of King William II as two angels fly around him. For the Angevins, the sacred nature of their rule was even more personalized. Embodying a concept known as beata stirps (Latin for blessed lineage), God, acting through Louis, approved Robert’s rule of southern Italy. Robert reinforced his blessed lineage by counting multiple saints in his extended family—including his father’s uncle, Saint Louis IX of France, and Saint Elizabeth of Hungary on his mother’s side. When Robert died in 1343 without a male heir, he went against the tradition of only male succession and insisted that the throne be passed to his granddaughter Joanna, so as to preserve the sacred bloodline of the Angevin rulers in Naples.

Robert of Anjou (detail), Simone Martini, Saint Louis of Toulouse, c. 1317, tempera, gold, and gems (lost) on panel, 121.6 x 74.2 inches (Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

This depiction of Robert looks like other portraits of him, indicating that artists followed a specific prototype. We do not know whether these portraits were based on first-hand observation though. His slim face, long nose, downturned mouth, and pointed chin is repeated in nearly every royal image of Robert from the 14th century.

King Robert enthroned with Virtues and Vices (detail), Anjou Bible, folio 3 verso, made in Naples c. 1340 (KU Leuven Maurits Sabbe Library, Belgium)

Gigliato of Robert the Wise, minted in Naples c. 1309–45, billon (copper alloy containing gold and silver), 12 x 26.9 millimeters (Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven)

A prominent example is found in a page from the Anjou Bible made in Naples. In the illuminated manuscript, Robert appears older, but with identical features and similarly framed in a monumental Angevin crest. He is also enthroned on the lion-headed (and clawed) throne that his brother occupies in the Simone Martini panel. The lion throne is used again in the image stamped on the gigliato (pronounced jil-yato), the official coin of the Kingdom of Naples during Robert’s rule. Maybe the King specifically repeated these elements to reinforce his legitimacy as Louis’s divinely sanctioned replacement.

Regardless of Robert’s motives, at least one thing is certain: Simone Martini’s magnificent altarpiece of Saint Louis of Toulouse projects a legacy of sacred Angevin succession, a record of international exchange, and the story of a Franciscan saint who gave up his right to rule the Kingdom of Naples.