Written by Jana Igunma, Lead curator, Buddhism, The British Library

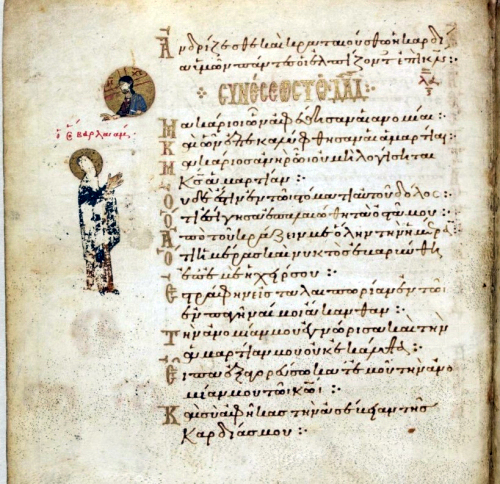

A mention of the legend of Barlaam and Josaphat in a marginal illustration in a manuscript famously known as the ‘Theodore Psalter’, although the story itself is not narrated here. Theodore, proto-presbyter of the Studios Monastery in Constantinople, made the manuscript in ancient Greek for Abbot Michael, in 1066 CE. British Library, Add MS 19352 f.34v

Europeans became increasingly interested in the cultures and religions of the Middle East and Asia, or what they later called ‘the Orient’, as a result of trade relations throughout the first millennium C.E. Images of Buddha with the Greek lettering ΒΟΔΔΟ (‘Boddo’ for Buddha) were found on gold coins from the Kushan empire dating back to the second century C.E. Buddha was mentioned in a Greek source, Stromateis, by Clement of Alexandria as early as around 200 C.E., and another reference to Buddha is found in St Jerome’s Adversus Jovinianum written in 393 C.E.

A religious legend inspired by the narrative of the “Life of Buddha” was well known in the Judaeo-Persian tradition and early versions in Persian, Arabic, Hebrew, Armenian, and Georgian have been discovered. The story became commonly known as “Barlaam and Josaphat” in medieval Europe. The name Josaphat, in Persian and Arabic spelled variously Budasf, Budasaf, Yudasaf, or Iosaph, is a corruption of the title Bodhisattva which stands for “Buddha-to-be,” referring to Prince Siddhartha who became Gotama Buddha with his enlightenment.

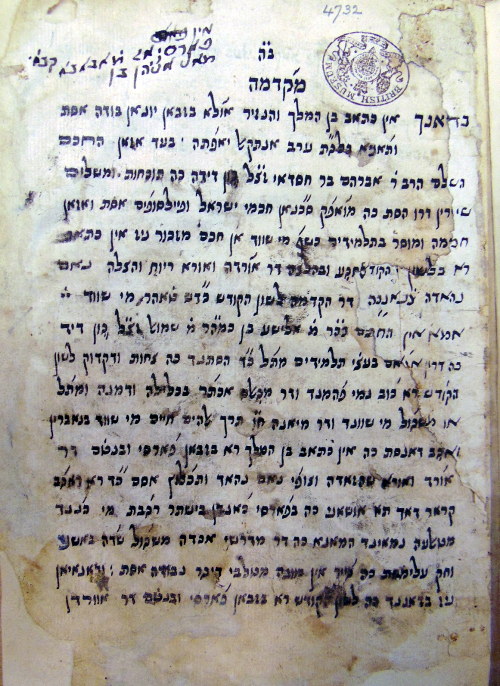

First page of an 18th-19th century poetical version of Barlaam and Josaphat with the title Shāhzādah ṿe-Tsūfī by Elisha ben Samuel in Persian in Hebrew characters. British Library, Or.4732 f.1r

Fragments of early versions of the legend seem to have been preserved in Manichean texts in Uighur and Persian from Turfan, and it is thought that Manicheans may have transmitted the Buddha narrative to the West. From there the story was translated into Arabic, and into Judeo-Persian and Syriac. An early Greek version is attributed to St John of Damascus (c. 675–749 C.E.) in most medieval sources, although recent researches reject this attribution as it is more probable that the Georgian monastic Euthymios carried out the translation from Georgian into Greek in the 10th century C.E. It became particularly popular throughout the Christian world after it was translated into many different languages in the Middle Ages, including Latin, French, Provençal, Italian, Spanish, English, Irish, German, Czech, Serbian, Dutch, Norwegian, and Swedish.

The spread of the legend of Barlaam and Josaphat in medieval Europe was a cultural phenomenon second to none at the time. Poetic and dramatized versions of the legend became what today would be called ‘bestsellers’. In Christian Europe these two names were commonly known and the Buddha as St Josaphat became a Saint with his own feast day in the Christian calendar: 27 November.

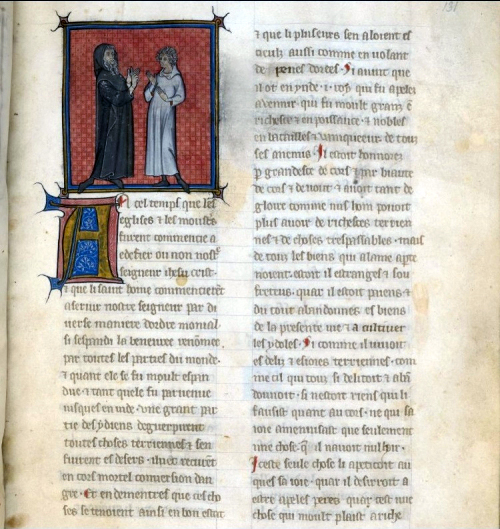

Devotional Miscellany in Old French including the legend of Barlaam and Josaphat on 69 pages, France, first half of the 14th century. The illustration depicts Barlaam in black and Josaphat in white dress. British Library, Egerton MS 745 f. 131

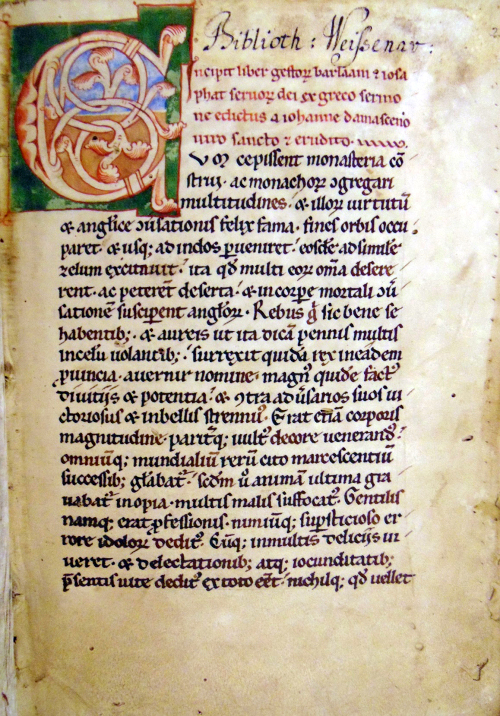

A 12th-century Latin translation of Barlaam and Josaphat from the Greek version attributed to John of Damascus. The manuscript was owned by the Weissenau Abbey in Germany. British Library, Add MS 35111 f. 2

Although based on the narrative of the Life of Buddha, the content of the legend of Barlaam and Josaphat was reshaped and supplemented to make it suitable for the Christian believer. In the Christianized story, an astrologer predicts that the newly-born son of King Avennir (or Abenner) in India, Josaphat, will become a follower of the Christian religion. To prevent this, the king forbade his son to leave the royal palace. The young prince was brought up in ignorance of sickness, old age and death. However, he found out about the dangers to life during excursions from the palace when he met a leper and a blind man, a decrepit old man and finally a corpse. To this point the parallels between the Buddha narrative and the legend of Barlaam and Josaphat are obvious, although names have been corrupted: King Suddhodana became King Avennir, and Prince Siddhartha became Josaphat (for Bodhisattva). Then events in the legend of Barlaam and Josaphat take a different turn, and some figures are mixed up with others, like for example Buddha’s enemy Devadatta and Mara, the lord of desire.

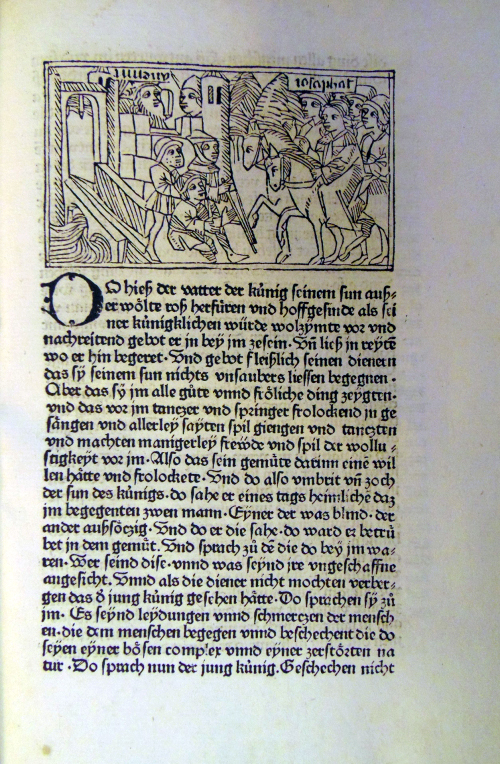

An illustrated German version of Barlaam and Josaphat, printed in Augsburg around 1470 CE. Shown here is an illustration of Josasphat’s encounter of a blind man and a leper, and the text narrates how his attendants explain the reality of human suffering to him. British Library, IB.5919

A German version continues that after learning about sickness, old age and death, Josaphat met the Christian hermit Barlaam who converted him. Josaphat’s father attempted to dislodge his son from his new faith. He threatened him and then he promised him half the kingdom, but without success. Then the king met the sorcerer Theodas – a corruption of the name Devadatta – who advised him to send Josaphat beautiful women to seduce him, in which they did not succeed. In the Buddha narrative this scene is related to Mara instead of Devadatta. Josaphat was also attacked by Theodas’ evil spirits which he fought off.

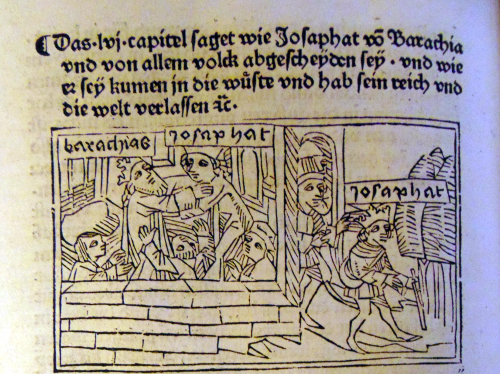

llustration of Josaphat’s (or the Bodhisattva’s) renunciation of the world in a German printed version from Augsburg, c. 1470 CE. He takes his leave from Barachias (left), whom he made king, and then embarks on the path of an ascetic (right). British Library, IB.5919

Josaphat decided to renounce the world and to spend the rest of his life as an ascetic. In the wilderness of the desert he was attacked by wild beasts and demons. Finally he was re-united with the hermit Barlaam, and they passed away shortly after one another.

The legend became particularly popular in Germany through the Austrian poet Rudolf von Ems’ poetic German version that was composed on the basis of a Latin version around 1230 C.E. In Scandinavia a translation into Old Norse was ordered by King Haakon Haakonsøn in the 13th century, which was the basis of later translations into Norwegian and Swedish. From a Syriac version translations into Old Slavonic and then Russian and Serbian were produced.

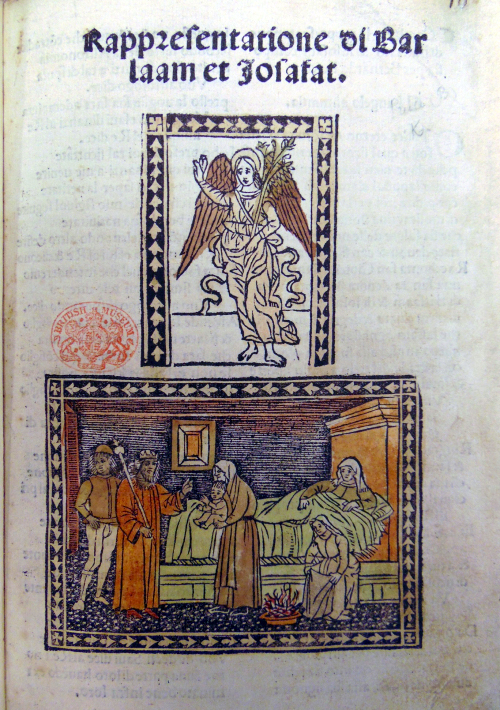

Rappresentatione di Barlaam et Josafat, an Italian poetic version by Bernardo Pulci printed in Florence in 1516 CE. The title page illustration depicts the birth of Josaphat in the imagination of a Christian artist. British Library, 11426.dd.24, title page

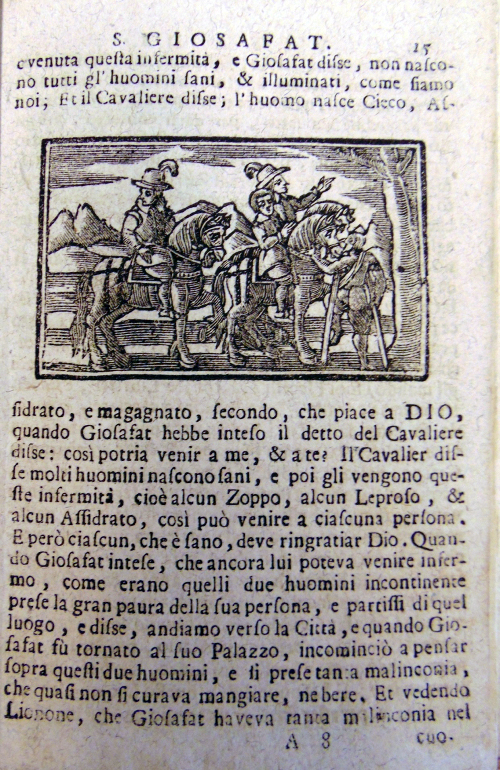

Illustrated Italian version of Barlaam and Josaphat printed in Venice around 1650 CE. The illustration depicts one of the four signs: Josaphat’s encounter with a sick man (a leper). British Library, 4827.a.31 p.15

Printing technology helped to mass-produce copies of the legend of Barlaam and Josaphat which made it more widely accessible. Frequently, pictures of Barlaam and Josaphat were added on the title page of printed works. Illustrations depicting scenes from the story were included in some printed books. Although the artistic representation of such images is characterized by the European fashion of that time, based on the imagination of artists who had never been to India, it is possible to identify certain scenes that are well known from the Life of Buddha. These include the Buddha’s birth as a prince, his four encounters, his renunciation of the world, Mara’s attack and assaults by Devadatta.

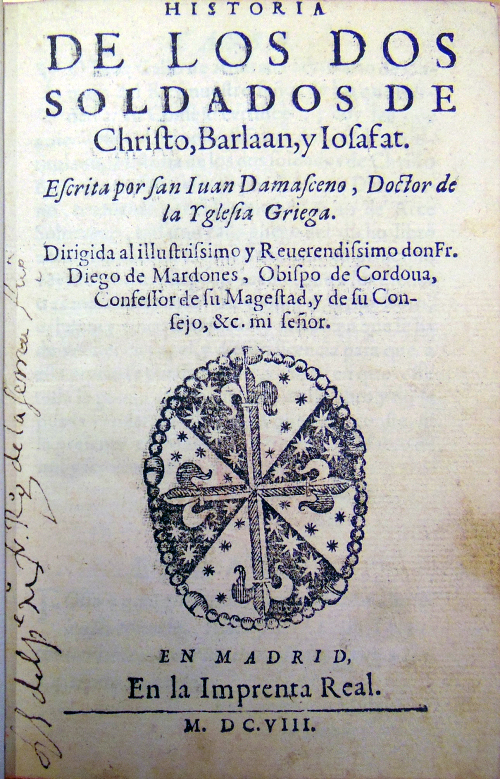

Title page of a version in Spanish which attributes the legend to John of Damascus, ‘Doctor of the Greek Church’. It was printed in Madrid in 1608 CE. British Library, 4823.a.13, title page

Europe was not the final destination of the Buddha narrative in form of the legend of Barlaam and Josaphat. The existence of the story was also known in Ethiopia, perhaps well before the 16th century. It was documented by Abha Bahrey, a 16th-century Ethiopian historian who mentioned the book, possibly a translation into Ge’ez (Ethiopic) from Greek, in his ‘Psalter of Christ’ dated 1528 C.E. After the official adoption of Christianity in 330 C.E., Ethiopian Christians began to translate the sacred texts: the Bible, the New Testament and the Pentateuch into the Ge’ez language. Many writings that were first compiled in Aramaic or Greek have been fully preserved only in Ge’ez as the sacred books of the Ethiopian Church. There is a vast corpus of scriptures that have survived exclusively only in Ge’ez.

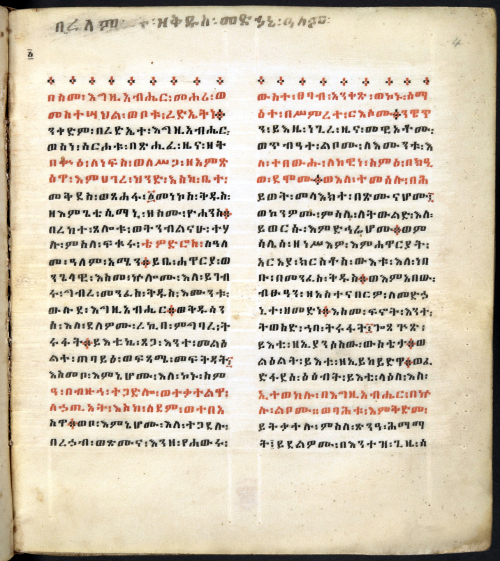

Handwritten version of Barlaam and Josaphat in Ge’ez (Ethiopic) with the title ‘Baralam and Yewasef’, copied at around 1746-55 from an older translation from Arabic into Ge’ez. British Library, Or. 699 f. 4

Another translation into Ge’ez with the title Baralam and Yewasef was executed from the Arabic version of Bar-sauma ibn Abu ‘l-Faraj by one ‘Enbiikom’, or Habakkuk, for king ‘Galawdewds’, or Claudius. It is dated ‘A.M. 7045’ which corresponds to 1553 C.E. A surviving copy was written during the reign of king ‘Iyasu II. (1730–55 C.E.).

With thanks to Urs App for inspiration, and to Eyob Derillo, Ilana Tahan, Ursula Sims-Williams, Adrian Edwards, Andrea Clarke and Ven. Mahinda Deegalle for their advice and support.

Jana Igunma, Lead curator, Buddhism

Originally published on the British Library blog

Additional resources:

Barlaam and Iosaph. Encyclopaedia Iranica

Budge, E. A. W. S. Baralâm and Yĕwâsěf: Being the Ethiopic version of a Christianized recension of the Buddhist legend of the Buddha and the Bodhisattva. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1923

Cordoni, Constanza and Matthias Meyer (ed.) Barlaam und Josaphat: Neue Perspektiven auf ein Europäisches Phänomen. Berlin, Munich, Boston: De Gruyter, 2015

Hayes, Will. How the Buddha became a Christian Saint. Dublin: Order of the Great Companions, 1931

Schulz, Siegfried A. “Two Christian Saints? The Barlaam and Josaphat Legend.” India International Centre Quarterly, vol. 8, no. 2, 1981, pp. 131–143.

Toumpouri, Marina. Barlaam and Iosaph. A companion to Byzantine illustrated manuscripts edited by Vasiliki Tsamakda. Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2017, pp. 149-168