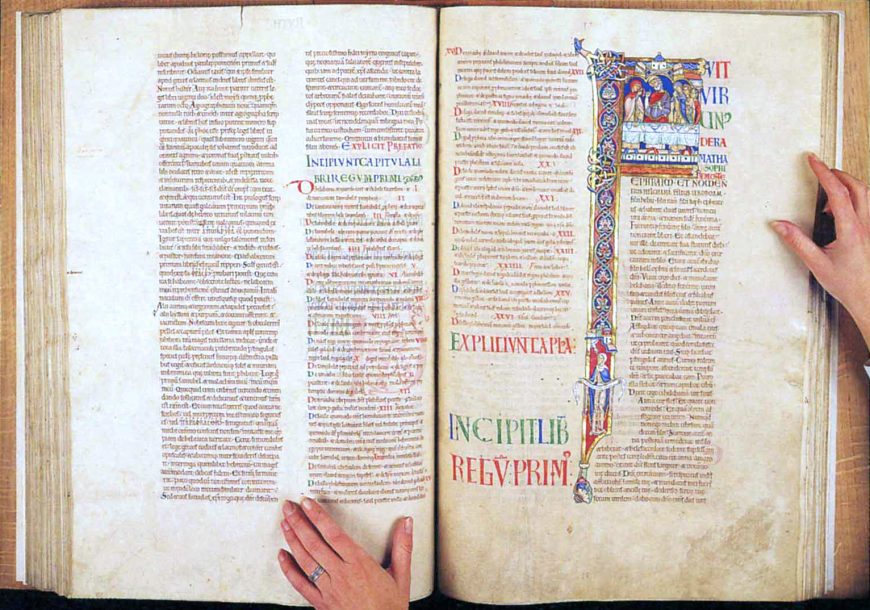

The page above, known as the Morgan Leaf, comes from the Winchester Bible, one of the most magnificent illuminated manuscripts to have been made in England in the twelfth century. The Morgan Leaf, which is now in the Morgan Library & Museum in New York (hence its name) was originally inserted as a frontispiece to the Book of Samuel in the Winchester Bible.

The Winchester Bible (below) was made at the Cathedral priory of St. Swithun’s at Winchester, England and is still at Winchester (where it is normally on display—though without the Morgan Leaf).

The Winchester Bible is an example of a type of book known as a giant bible, a large format manuscript that originated in Italy in the mid-eleventh century and contained the entire text of the Christian bible from the Book of Genesis to Revelation. Giant bibles were deemed to be essential to monastic communities during the Romanesque period. Its importance should be seen within the context of the Gregorian reform movement, named after Pope Gregory VII, who ruled from 1073 until 1085. Gregory initiated reforms in the late eleventh century requiring that monks have access to an accurate version of the entire text of the Bible. Prior to the eleventh century, entire texts of the Bible were relatively rare.

The translated inscription reads: Art comes before gold and gems, the author before everything. Henry, alive in bronze, gives gifts to God. Henry, whose fame commends him to men, whose character commends him to the heavens, a man equal in mind to the Muses and in eloquence higher than Marcus [that is, Cicero]

It is generally assumed that the patron of the Winchester Bible was Henry of Blois, the bishop of Winchester, and one of the most powerful men in England. There is, however, no conclusive proof of this, and his patronage has recently been questioned with the alternate suggestion that King Henry II may have played a role in supporting production of this lavish manuscript. Royal patronage may explain some of the imagery seen in the Morgan Leaf.

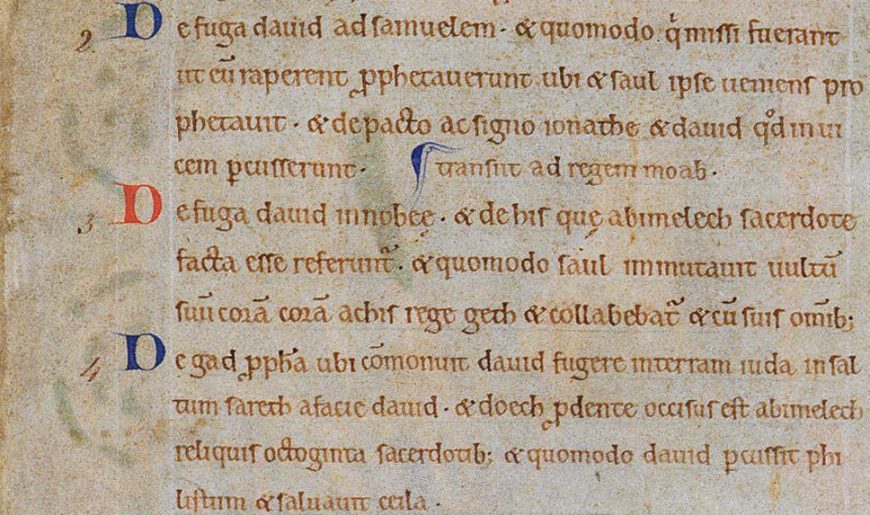

The Winchester Bible is written on parchment made from calf skin. It has been estimated its production would have required the skin of over 250 calves, and so this would have been an exceptionally expensive book to produce—not even accounting for the skilled labor of the scribe and the illuminators. The entire text of the Bible was written in one beautifully rounded hand (which can be seen on the verso of the Morgan Leaf). The writing would have been a formidable task, and it has been estimated that the project would have taken at least four years. The scribe was most probably a monk from the monastic community at St. Swithun’s, though lay scribes have also been recorded at work at Winchester.

Illustrating the Winchester Bible appears to have been a more complicated affair. The intention was to prefix each book of the Bible with an historiated initial (one with a figurative illustration in it), usually related to the text. As an afterthought, full-page frontispieces to three books of the Bible were added (one of which is the Morgan Leaf). The illustrations were drawn and painted by at least six different artists, probably working in two separate and consecutive teams, yet in spite of this, the program of illustrations was left incomplete, with many illustrations left half-painted or only under-drawn. The six artists remain anonymous, but names have been invented to distinguish their different styles. The two responsible for the Morgan Leaf are know as the Master of the Apocrypha Drawings and the Master of the Morgan Leaf.

The scenes on the Morgan Leaf are set against colored, paneled backgrounds that visually project them forward. The artist uses a characteristic narrative device of the period, arranging scenes in pairs, with the first representing the scene before, and the second the scene after. The scene in the top register on the left, for example, represents the diminutive figure of David who is shown slinging the stone at the giant Goliath, while on the right, he cuts off the head of Goliath as the Philistines flee.

Notice that David is represented clothed but without armor, conforming to the biblical account, but not, as in later Renaissance representations, naked. In the second register, David is represented on the left, playing the harp in front of King Saul, who in a fit of jealousy throws a spear at him. In the pendant image on the right, David is anointed Saul’s successor by the priest Samuel, after Saul commits suicide. In the bottom register on the left, Absalom, the son of David, is put to death, and in the final scene, to the right, David is informed of the death of his son and weeps in grief.

It has been suggested that this event parallels one in the life of King Henry II as his own son and heir, Henry the Young King, revolted against him and in the process lost his life, which caused Henry great grief. One distinctive feature is the striped, chequered, and chevron patterns on the shields. This has been identified as a form of proto-heraldry, which had its origins in the practice of attaching cloth coverings to shields so as to distinguish between combatants dressed in armor who would otherwise not have been easily identifiable.

In its execution, there is a division of labor in the illumination of the leaf, with the underdrawing done by the Master of the Apocrypha Figures, and the painting largely done by the Master of the Morgan Leaf. Of these, the more traditional was the Master of the Aprocrypha drawings, who belonged to the first team of artists, and, it has been suggested, worked earlier at the monastery of St. Albans north of London. The more precocious of the two artists, the Master of the Morgan Leaf, belonged to the second team. The Master of the Morgan Leaf appears to have been a more cosmopolitan artist than his predecessor. The painter was almost certainly a lay professional, an itinerant artist who moved from one international center to another.

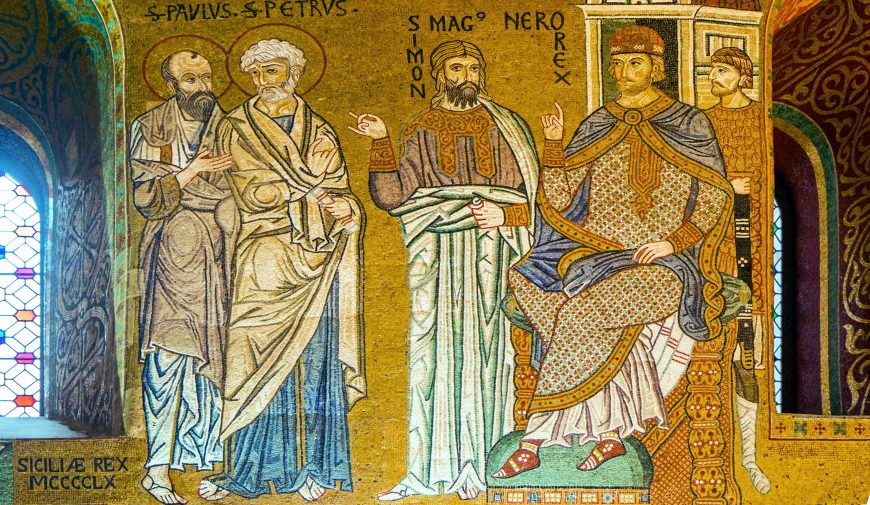

It has been postulated that the Master of the Morgan Leaf had seen the monumental mosaics in Sicily in the Palatine chapel at Palermo and the abbey at nearby Monreale, which had only recently been installed. It is thought that he translated the Byzantine style and imagery he had seen there into the medium of manuscript illumination. His hand has also been identified in the wall-paintings in the royal convent of Sigena in Aragon in northern Spain, which must have been painted after he left Winchester.

During this period, England, Sicily, and Aragon were closely linked through dynastic ties and England was far more open to international influences than in the previous Anglo-Saxon era, with the Angevin empire of Henry II extending as far as the south of France. The painting of the Morgan leaf is unprecedented in English art in its naturalism and representation of human emotions, especially pathos and grief. This artistic expressiveness anticipates, by a century, the work of Duccio in Italy.

The chronology of the Bible’s execution has been the subject of dispute. It is generally thought to have been begun about 1160, but its terminal date is more controversial, with some experts favoring a date in the 1170s, corresponding to the death of Henry of Blois in 1171, while others think work may have continued beyond this date into the 1180s. The recto of the Morgan Leaf is divided into three horizontal registers, a format that recalls the great gospel books made at the monastery of Echternach, now in Luxembourg, which in the eleventh century formed part of the Holy Roman Empire. One of these manuscripts may have been in England in the twelfth century and functioned as an exemplar for the page format for the Morgan Leaf.

Additional resources:

The Morgan Leaf at the Morgan Library & Museum

Claire Donovan, The Winchester Bible (British Library: London, 1993)

Christopher Norton, “King Henry II, St Hugh, and the Winchester Bible,” in Romanesque patrons and processes : design and instrumentality in the art and architecture of Romanesque Europe, edited by Jordi Camps i Sòria, Manuel A. Castiñeiras, John McNeill and Richard Plant (London: Routledge, 2018)

National Manuscripts Conversation Trust regarding the manuscript

Morgan Library & Museum conservation poster regarding the Morgan Leaf

The Winchester Bible exhibition blog at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Three lectures on The Winchester Bible (2015) with:

• Charles T. Little, Metropolitan Museum of Art

• Stephen Murray, Columbia University

• Christopher de Hamel, University of Cambridge