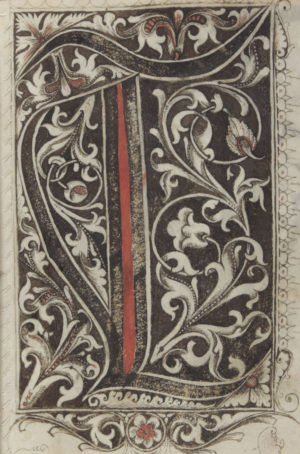

Initial letter T, Gregorius Bock, Medieval Scribal Pattern Book, 1510–17 (Beinecke Library, Yale, MS 439, folio 48 recto)

This essay is devoted to a particularly attractive and rare kind of medieval manuscript: the model book. A feast to the eye, the object is filled with drawings and paintings that were meant to show scribes and illuminators how to decorate letters, paint initials, or add large segments of decoration to the page. Within this tradition, two types of model books can roughly be distinguished. Some functioned as instruction manuals. In these books, the drawings might be accompanied by a narrative or explanation that instructs the artisan how to proceed, usually in a step-by-step process. Other model books appear to have merely functioned as a source of inspiration: they present a wide array of shapes and drawings from which the artisan could take his pick.

The level of sophistication among surviving model books varies considerably. On the lower end of the spectrum there are pattern books that merely show how to make enlarged letters with some minor flourishing. On the higher end, by contrast, there are copies with high-quality stand-alone designs and sophisticated historiated initials inhabited by figures and scenes. Evidently the requirements of the artisans varied; and by proxy, so did the taste of medieval readers. It is this variation that makes model books so fascinating, both as physical objects and as cultural artifacts.

Plainly decorated letters

To start at the lower end of the spectrum, some model books merely showed scribes how to execute a certain script or how to draw plain enlarged capitals—the most basic kind of decoration.

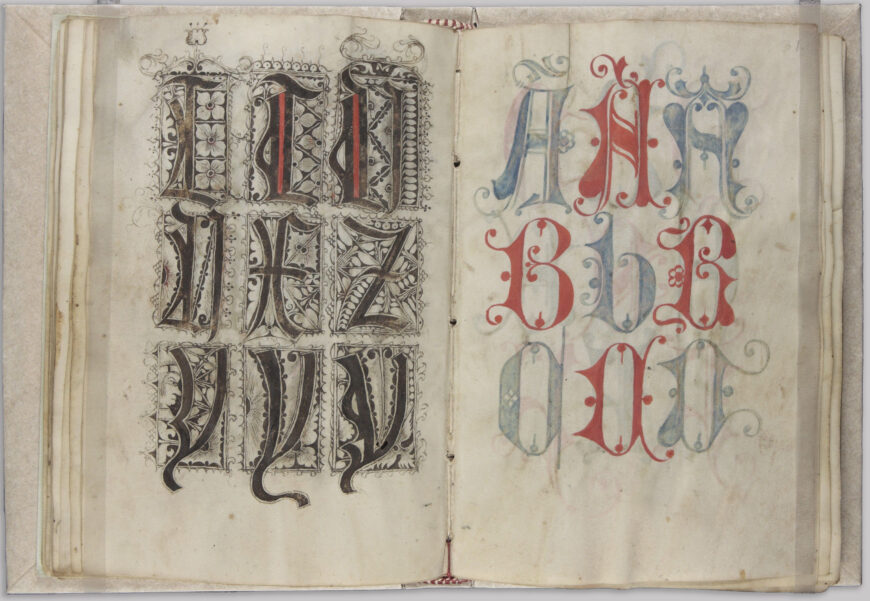

Gregorius Bock, Medieval Scribal Pattern Book, c. 1510–17 (Beinecke Library, Yale, MS 439, folios 30 verso–31 recto)

The book opening seen above is from Gregorius Bock’s Scribal Pattern Book, which provides instruction on both fronts. Produced in 1510–17, the first part of the small parchment book contains a series of alphabets in different scripts, some of which are clearly influenced by print typefaces. The second part contains decorative initials arranged in alphabetical order. In the introduction to his manual, Gregorius adds a dedication to his cousin Heinrich Lercher Wyss of Stuttgart, who was scribe to the Duke of Württemberg. The arrangement of the material shows how Heinrich likely used the book: he would thumb through its pages until he had reached either an alphabet or capital letter to his liking.

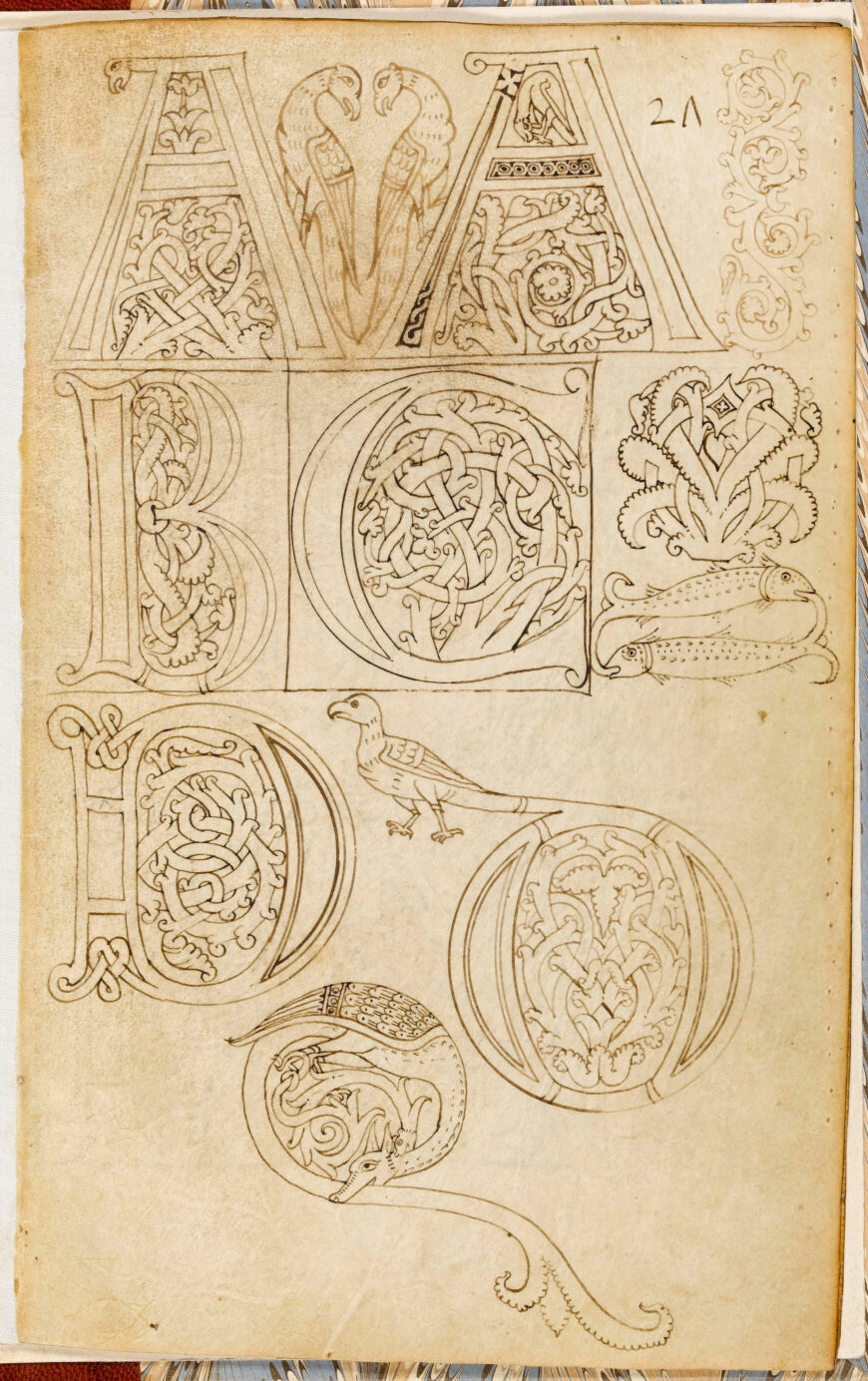

Model book (probably made in Florence), c. 1150–75 (Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, MS 83–1972, folio 1 recto)

While Bock’s letters are a pleasure to look at, especially for the book historian, his designs are not exactly rocket science. More complex—but still relatively plain—are the models provided by a much older pattern book in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. This appears to be the oldest surviving pattern book for initials: it dates from c. 1150 and was produced and used in a Tuscan workshop. The choice is much more limited than in the previous example: the Cambridge copy does not provide multiple alphabets, nor does it present a wide range of initials (in fact, only about twenty are present). Interestingly, some manuscripts survive in which we encounter decorated letters that could well be modeled from this or a similar model book (like British Library, Harley MS 7183).

Letter K: from the “Macclesfield Alphabet Book,” 15th–16th century (British Library, London, Add. MS 88887, folio 17 recto)

Elaborately decorated letters

On the more upscale end of things is the model book known as the Macclesfield Alphabet Book. It was made and used in 15th-century England, apparently for the transmission of ideas to decorators or their assistants.

The artisans were offered quite a lot of choice, given that we encounter no less than fourteen different alphabets on its pages. What makes this book so special, however, is their quality and the manner in which the letters are designed: their shapes are produced by human figures in various uncomfortable positions—doing yoga exercises, it seems.

Giovannino de Grassi, Alphabet Book, late 14th century (Biblioteca Civica, Bergamo, MS Cassaf. 1.21)

Anonymous Lombard (workshop of Giovannino de Grassi), Two Studies of a Cheetah, 1410, watercolor and bodycolor on vellum, 16.4 x 12.3 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

A similar subject matter is encountered in the alphabet book of the Italian artist Giovannino de Grassi. This book was created at the Visconti court in Milan and features both initial letters and stand-alone drawings. The Visconti’s were important patrons of the arts and so it makes sense that we see their generosity extend into the world of book production.

Giovannino was known for depicting exotic animals in their natural habitat and this book features such images as well. His pages provided models for other artists who wished to replicate his realistic depictions (the image of the cheetah is from his workshop).

Marginal decoration

Even more sophisticated are model books that show how to create elaborate decoration that runs in the margin along the length of the page. These border decorations, with their curly leaves and unexpected turns, could be tricky to produce.

Model book and the same decoration executed in an actual book. Left: Göttingen Model Book, c. 1450 (Universitätsbibliothek, Göttingen, MS Uffenbach 51, folios 2 verso–3 recto); right: Gutenberg Bible, volume 3, c. 1455 (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris)

The so-called Göttingen Model Book, made around 1450, provides a solution to this problem. Its pages not only show, step by step, how to build a 3D leaf pattern, they also present detailed instructions like the following:

The foliage one shall first draw with a lead or a point. Then one shall outline the foliage with a pen and with very thin ink or with thin black color. Then one shall polish the foliage with a tooth, so that the color can be applied smoothly, but not too firmly. Then one shall paint it with the colors, one side right and the other side left or reversed, with a brush, namely light red and green. […] Göttingen Model Book, MS Uffenbach 51, c. 1450

The drawings and narrative clearly complement one another. From time to time the instructions mention something like “as it is shown here” or “as the image shows.” A model book can hardly be clearer than this: while the alphabet books shown above were more or less meant to simply inspire the artist, the Göttingen book really takes the artist by the hand and guides him through each step of the production process. The instructions apparently worked well, as is shown by a surviving Gutenburg Bible that contains these very leafy borders.

The final point

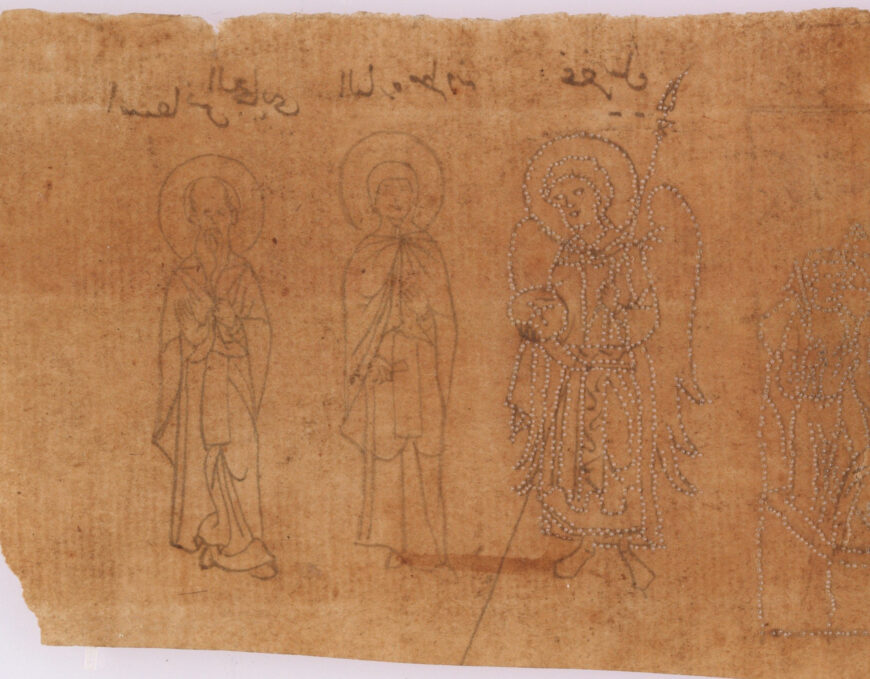

Models are crucial in any learning process. Observing how something is done helps you acquire a skill you lack as much as it encourages you to develop further those you already have. Moreover, there is an additional use to these pattern books that has not yet been mentioned: patrons visiting artisans’ shops could well have been given these objects to find out what the book-maker was capable of providing. Given its many uses, it is hardly surprising that the tradition is also encountered in other cultures, including Byzantine and Arabic book production.

Outline drawings from a pattern book, 1400–1700 (Beinecke Library, Yale, MS 553)

One particularly unusual Arabic specimen deserves to make the final point. The fragment shown above presented Arabic decorators with models of scenes from the New Testament. It figures that the artisans, used to decorating the Qur’an, needed a little inspiration when it came to the Bible. This specimen is also interesting because some of the figures have been outlined by tiny holes, meaning that the sheet could be used as “tracing paper” (click the image to see this closer). While this ultimate instruction method took all potential flaws and creativity out of the modeling process, it allowed decorators with lesser talents to produce something beautiful.