Installation view, New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-altered Landscape, 1975, George Eastman Museum

When you think of “landscape photography,” what comes to mind? Whatever pictures you’re imagining, they likely look different from the photographs in the 1975 exhibition New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-altered Landscape. Organized at the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, New York, the show featured ten photographers who examined the American landscape in a new way.[1] Instead of focusing on pristine or exceptional scenery found at national parks, they trained their cameras on the byproducts of postwar suburban expansion: freeways, gas stations, industrial parks, and tract homes. They furthermore rendered these banal subjects with a style that suggested cool detachment. While visiting the exhibition, people voiced a range of reactions:

“I don’t like them—they’re dull and flat. There’s no people, no involvement, nothing.”

“At first it’s stark nothing, but then you look at it, and it’s just about the way things are.”

“I don’t like to think there are ugly streets in America, but when it’s shown to you—without beautification—maybe it tells you how much more we need here.”[2]

Preserved within these comments are the expectations these visitors held about the American landscape and its representation. Given that people largely found the work off-putting and difficult to interpret, how did New Topographics come to be regarded as one of the most important photography exhibitions of the 20th century?

Landscape as the built environment

On the one hand, New Topographics represented a radical shift by redefining the subject of landscape photography as the built (as opposed to the natural) environment. To comprehend the significance of this, it helps to consider the type of imagery that previously dominated the genre in the United States.

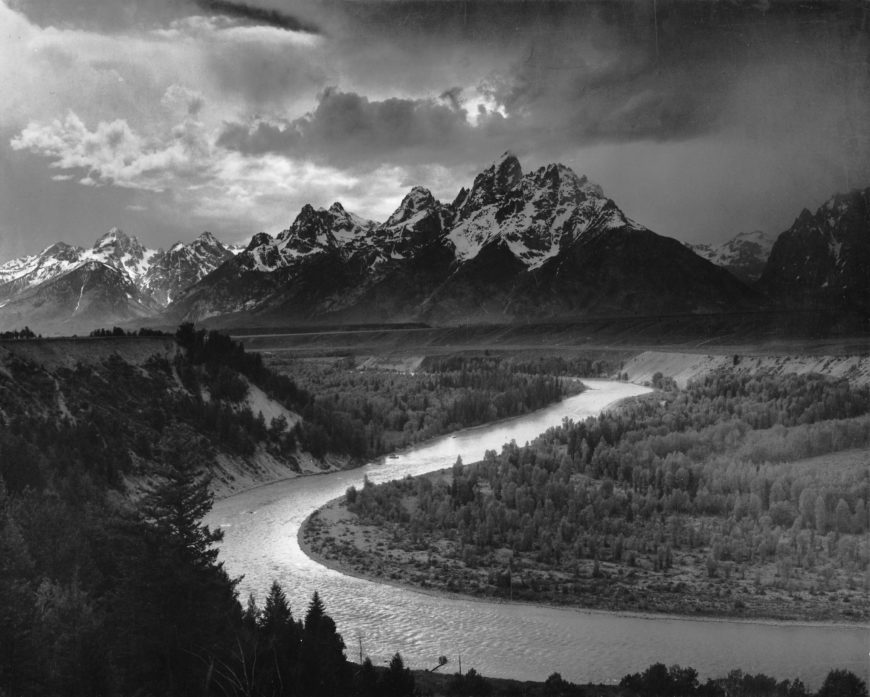

Beginning in the 1920s, Ansel Adams cultivated an approach to landscape photography that posited nature as separate from human presence. Consistent with earlier American landscape painting, Adams photographed scenery in a manner intended to provoke feelings of awe and pleasure in the viewer. He used vantage points that emphasized the towering scale of mountain peaks, and embraced a wide tonal range from black to white to record texture and dramatic effects of light and weather.

Ansel Adams, “The Tetons—Snake River,” Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming, 1942 (National Archives)

Adams wanted his pictures’ viewers to feel as uplifted as he had when looking at the scenery in person. His heroic, timeless photographs contributed to the cause of conservationism—the environmental approach that seeks to preserve exceptional landscapes and protect them from human intervention.

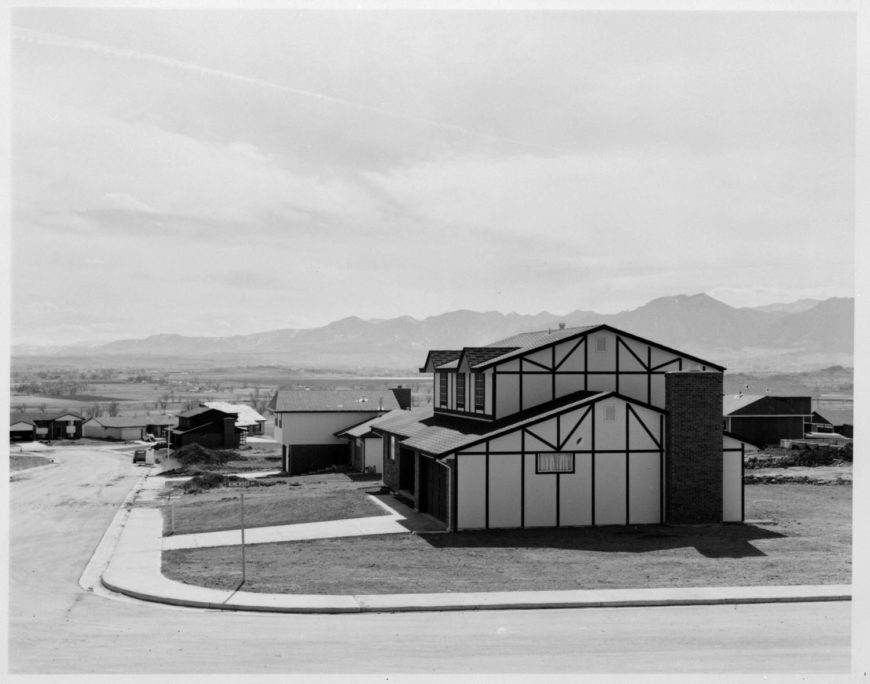

Robert Adams, Tract house, Boulder County, Colorado, 1973, gelatin silver print (George Eastman Museum, © Robert Adams)

By contrast, when visitors walked into New Topographics, they encountered subject matter that was all too commonplace, represented in an unfamiliar manner. Consider Robert Adams’s (no relation to Ansel) 1973 image Tract house, Boulder County, Colorado. The photograph pictures a two-story house whose half-timber framing appears decorative rather than structural, a kitschy imitation of an earlier architectural style.[3] Recorded under bright noon sunlight, the house’s shadow barely extends into its grassless yard. The flag on the mailbox is up, perhaps to signal the presence of outgoing mail, but there are few other signs of habitation. The hazy, organic contour of the distant mountain range—which the house’s roofline nearly interrupts—appears more durable than the newly constructed neighborhood. The sense of place is Colorado, but this is not the open frontier of myth. Here—as in John Schott’s photographs along Route 66, or Frank Gohlke’s views of paved-over Los Angeles—postwar suburban sprawl has overtaken nature (both Schott’s and Gohlke’s work was represented in the exhibition).

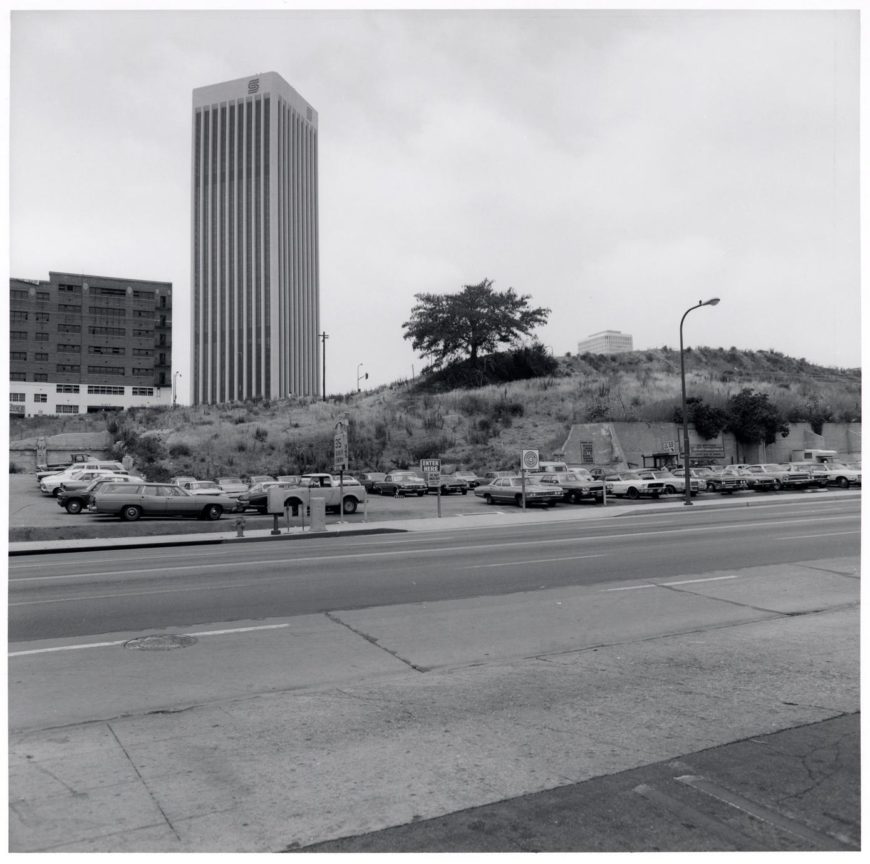

Frank Gohlke, Landscape, Los Angeles, 1974 (George Eastman House, © Frank Gohlke)

What was both novel and challenging about New Topographics was not only the photographs’ content, but how they made viewers feel. By foregrounding, rather than erasing human presence, the photographs placed people into a stance of responsibility towards the landscape’s future—a position that resonated with ecology, the branch of environmental thought that was gaining traction in the 1970s.

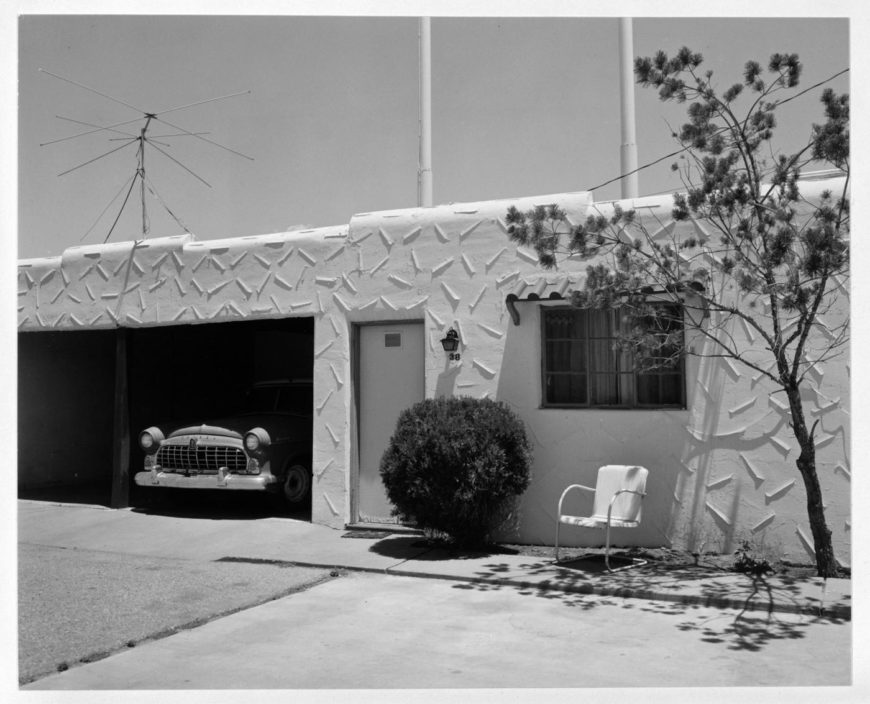

John Schott, Untitled (from Route 66 Motels), 1973, gelatin silver print, 19.3 x 23.9 cm (George Eastman Museum, © John Schott)

A “Neutral” style

In addition to subject matter, style was a major component of what distinguished New Topographics photography. In the exhibition’s catalog, curator William Jenkins described the photographs as “neutral” and “reduced to an essentially topographic state, conveying substantial amounts of visual information but eschewing entirely the aspects of beauty, emotion, and opinion.”[4] He wondered: was it possible to make pictures without style? The exhibition’s photographers all engaged with this question and pursued it through a variety of means.

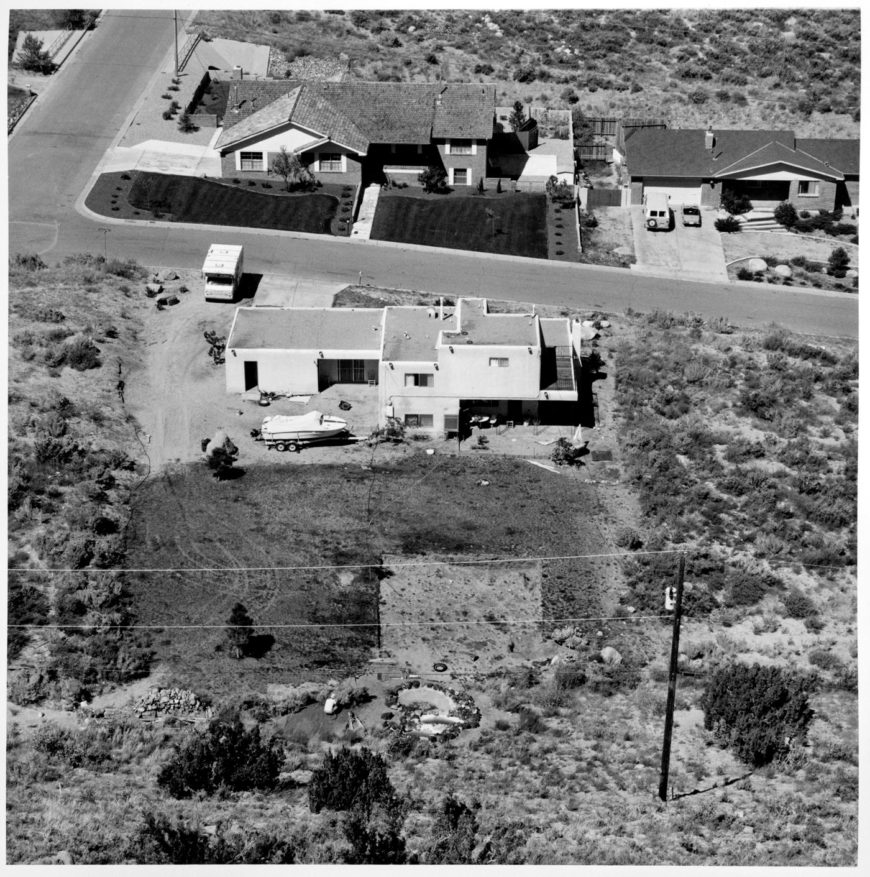

Working in square format, Joe Deal photographed new homes and construction sites in Albuquerque, New Mexico from the steep foothills of nearby mountains. Eliminating the horizon from his pictures, he filled each square frame with a dense patchwork of surfaces: driveways, newly cut roads, empty lots, and expanses of brush yet to be tamed. The effect was that the terrain appeared compressed into flatness, encouraging viewers to study the photographs as if looking at topographical maps. Their eyes suspended in a state of scanning, viewers could read the landscape as bearing traces of human decision-making. Moments of too-perfect symmetry in the patterns of rocks and bushes expose the landscaping as unnatural. Traces of ongoing development in the form of construction sites are juxtaposed with piles of refuse and empty lots that suggest the wastefulness of abandoned projects. By framing the land in this way, Deal enabled his viewers to consider the cost of rapid growth in the fragile desert.

Joe Deal, Untitled View (Albuquerque), 1973, gelatin silver print (George Eastman Museum, © Estate of Joe Deal)

New Topographics established that neutrality is as much a matter of convention as the expressivity of Ansel Adams’s photographs. If the photographs looked “neutral,” it was because they simultaneously resembled visual materials we associate with anonymity and information (such as topographical maps or real estate photographs), and activated the kind of looking we typically deploy to interpret those materials. Other New Topographics photographers also referred to fine art sources to inform their “neutral” style. For example, Lewis Baltz’s photographs of new industrial parks in Southern California invoked Minimalism. By photographing blank, corporate façades head-on, Baltz placed his viewers into a subtly critical confrontation with the homogeneity they represented.

Lewis Baltz, South Wall, Mazda Motors, 2121 East Main Street, Irvine, 1974, gelatin silver print (George Eastman Museum, © Estate of Lewis Baltz)

Influence and legacy

Though it received a lukewarm reception in 1975, New Topographics has been enormously influential in contemporary photography, both in terms of its attention to vernacular architecture and its cool, cerebral style. The exhibition was restaged in its entirety at multiple museum venues in 2009, a testament to its historical importance. Its photographers never considered themselves a school or movement, but the name of the show has come to serve as a kind of shorthand for the approach to landscape photography that they initiated. Many younger photographers collected and shared the exhibition’s catalog over the past several decades, and the ideas from the exhibition circulated among photography students—particularly influential were Stephen Shore (the exhibition’s sole color photographer) and Bernd and Hilla Becher (the only international photographers in the show). The Bechers’ students at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in Germany became known as the Düsseldorf School of Photography, and include the photographers Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, and Thomas Struth, who have each photographed the built environment using a similarly detached, unsentimental style that also harkens back to the New Objectivity tradition.

Stephen Shore, Church and 2nd Streets, Easton, Pennsylvania, June 20, 1974, 1974, chromogenic color print, © Stephen Shore

What New Topographics reinvented was both the subject matter of landscape and the kind of response we can have to such pictures: not just awe or uplift, but a sense of responsibility. As long as humans continue to intervene upon nature, this will remain a vital avenue of inquiry in contemporary photography.