Pablo Picasso, Guitar, 1914, sheet metal and wire, 30 1/2 x 13 3/4 x 7 5/8 inches (MoMA)

Picasso’s Guitar hangs from the wall like a painting or a real guitar, but we wouldn’t mistake it for either one. Unlike a painting, it’s a complex three-dimensional object, and it’s clearly not a functional guitar to be played. It’s an abstract representation of a guitar, an artwork, but one that doesn’t fit neatly into the tradition of Western representational sculpture. It is not a solid mass carved from marble or cast in bronze; it is not on a pedestal, nor is it attached to a background like a relief.

An unprecedented subject

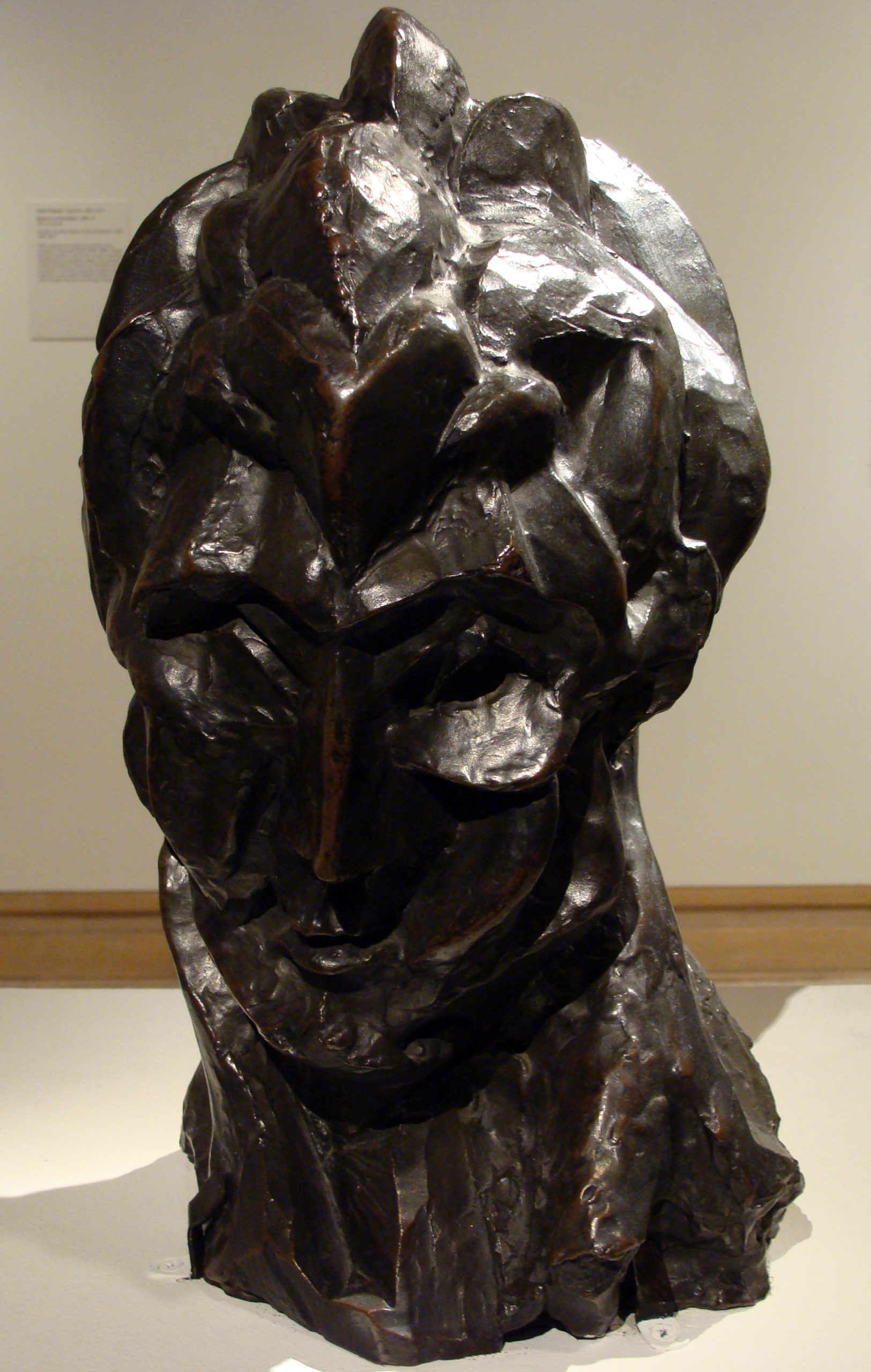

Furthermore, the guitar as a subject is unprecedented in a sculptural tradition almost exclusively devoted to representations of human and animal figures. Picasso’s own earliest Cubist-based sculptures were of a woman’s head.

Pablo Picasso, Woman’s Head (Fernande), 1909, bronze, 16 ¼ x 9 ¾ x 10 ½ inches, The Metropolitan Museum of Art (photo: Ben Sutherland, CC BY 2.0)

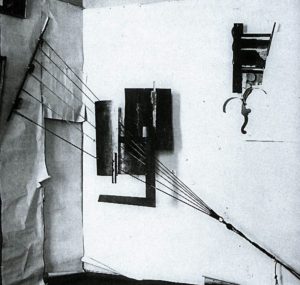

Picasso’s studio, Paris 1912 (MoMA)

Guitar represents Picasso’s attempt to expand his Cubist investigations of the ambiguities of represented form and space into three dimensions. Both Picasso and Braque began making paper and cardboard Cubist sculptures of still-life objects around the same time that they began making collages.

None of these early sculptures survive, and only a few photographs document their existence. They were, however, seen by other artists who visited Picasso’s and Braque’s studios. Vladimir Tatlin’s counter-reliefs were made in direct response to these early Cubist sculptures.

Innovations derived from an African mask

Pablo Picasso, Guitar, 1914, sheet metal and wire, 30 1/2 x 13 3/4 x 7 5/8 inches (MoMA)

The surviving sheet-metal Guitar in MoMA’s collection is a later version of a now lost cardboard model (also known as a maquette). It is an important work, not only because it is one of the earliest surviving Cubist sculptures by Picasso, but also because of what Picasso’s friend and art dealer D. H. Kahnweiler wrote about it. He claimed that the innovative treatment of forms in Guitar was directly derived from an African Grebo mask Picasso owned. In that mask the eyes are represented by projecting cylinders. Human eyes, of course, are recessed in the head and do not project out from the face. In Guitar Picasso used a similar strategy for representing the guitar’s sound hole as a tube projecting from the empty space at the base of the fretboard. Space becomes shaped forms, while solid forms — the body of the guitar in this case — become, in places, empty space.

Guitar follows the example of the Grebo mask in radically simplifying forms to basic geometric shapes and arranging them to convey information. We see the double curve of the guitar’s body in the flat frontal plane of the sculpture as well as a larger flat plane in the back. We also are shown the guitar’s hollowness by the rectangle cut into the guitar shape between the front and back curved planes. The cylinder projects from the center of this empty space; it is itself hollow, so it is both a projecting form and one signifying emptiness.

Kahnweiler explained that Picasso derived a crucial concept from the Grebo mask — that it was possible to use signs to represent things rather than imitating their appearance. This, far more than mere formal similarities, is central to understanding the way Picasso’s art as a whole was affected by insights prompted by African and Oceanic masks and sculptures. We recognize the facial features in the Grebo mask by the placement and relationship of the parts rather than their specific details. The mouth, for example, is simply a rectangle with stripes. Alone it would not be recognized as a mouth, but in the context of the mask it is a very effective representation of one.

A new type of sculpture

With Guitar, Picasso extended his collage explorations into three dimensions. By doing so he made a new type of sculpture, which is now called assemblage because it is assembled from multiple parts rather than formed as a single mass. The move into three dimensions added an important element to the work — cast shadows. These contribute to the visual complexity of Guitar by creating planes and patterns, and suggesting much greater depth and solidity than is actually created by the rather delicate metal planes. In this photograph the shadow projected on the wall to the left seems to represent the side of the guitar.

Of course, because it is a three dimensional object, the shadows projected by Guitar will change with changes in lighting. Shadows add an additional layer of complexity to Picasso’s Cubist investigation of the ambiguities that can arise from the juxtaposition of real things and their representations.

A workman’s lunch

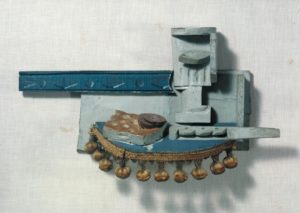

Pablo Picasso, Still LIfe, 1914, painted wood and upholstery fringe, 25.4 x 45.7 x 9.2 cm (Tate, London)

Picasso’s Still Life is another Cubist sculpture attached to a wall that plays with reality and representation. The still life subject is unconventional for a sculpture. It represents a working man’s simple lunch of sausage and bread accompanied by a glass of wine and a knife. All of the elements are painted wood except for a real piece of tasseled upholstery fringe attached to the semicircular plane representing the table top. The bread and sausage are crudely painted imitations of the subject, the knife is a simplified basic form, while the wineglass is Cubist in style. A strip of wood painted with a repeating pattern represents a decorative railing on the wall.

The sculpture uses a real decorative object, the strip of upholstery tassels, in combination with representations of objects depicted with varying degrees of naturalism. Adding to the complex display of reality and illusion is the painted decorative railing, which is attached to the wall as part of the sculpture, but could be a “real” decorative railing on the gallery wall.

Despite the inclusion of real objects and the realistically painted bread and sausage, Picasso clearly wanted the viewer to see Still Life as art, a hand-made object. The semi-circular plane representing the table top does not project from the wall at 90 degrees; it is tipped down like the table tops in Cubist paintings and collages, and could not support a real glass or knife. The quality of the workmanship is intentionally crude and roughly finished, in keeping with the simple workman’s lunch depicted.

Fine art versus craft

Still Life leads us to consider different possible approaches to representation and decoration, fine art and craft, and what they signify. The work juxtaposes the crafts of woodworking and upholstering, both associated with working class labor, with the illusionistic representation of still life objects associated with fine art. In uniting these two very differently-valued types of craft labor Picasso calls into question the traditional high valuation of the fine arts in relation to the so-called crafts, as well as challenging established distinctions between fine art and decoration. Known for his working class sympathies, Picasso here seems to claim an affinity with the artisans who work in the decorating trades.

Although they were little known at the time they were made, the innovations of Picasso’s Cubist assemblages foreshadowed many developments of twentieth-century sculpture. His use of found materials, rejection of the traditional materials and techniques of European sculpture, and elimination of a clear distinction between artwork and object make his early Cubist assemblages important early contributions to the breakdown between art and life that would become a key theme of twentieth-century sculpture.

Additional resources:

Picasso: Guitars 1912-1914 at the Museum of Modern Art, New York

A Technical Study of Picasso’s Construction Still Life, 1914 in the Tate Papers