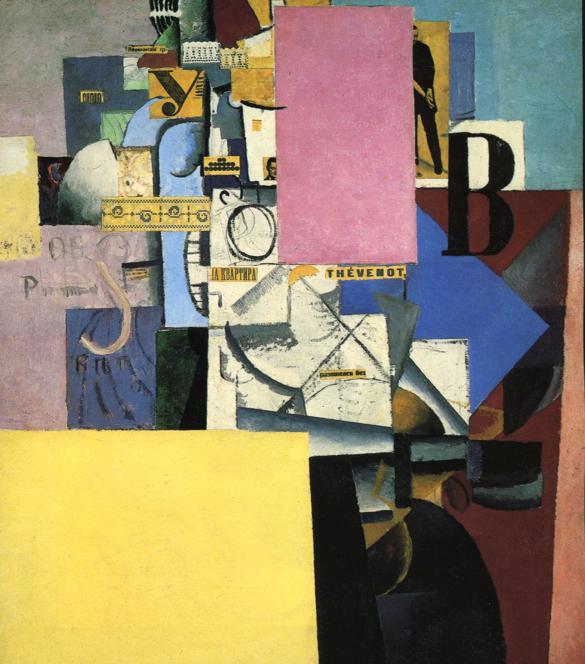

Kazimir Malevich, Reservist of the First Division, 1914, oil, collage, and thermometer on canvas, 21 1/8” x 17 5/8” (MoMA)

Kazimir Malevich created Reservist of the First Division (1914) in the first year of World War I. The title refers to a member of the reserve army waiting to be called up for military service, and it had personal significance as Malevich was himself a reservist (although not in the First Division). He was anxious about going to war, but the painting does not convey any obvious emotion or even a clear message. It is a combination of oil paint and collage in a style related to the Synthetic Cubism of Picasso and Braque. At the time Malevich was part of a group of Russian modern artists known as Cubo-Futurists, who used pictorial techniques initially developed by modern artists in Western Europe.

Combining representations

Like Synthetic Cubist paintings, Malevich’s Reservist of the First Division combines different systems of representation. Several objects are depicted using naturalistic techniques — a white cylinder projecting towards the viewer in the middle of the painting and a green cylinder on the left cast shadows and have traditional chiaroscuro shading to indicate their curved shapes. On the right a human ear is clearly depicted. There are also two immediately recognizable schematic objects — a gold cross just to the left of center at the top, and below it half of a black handlebar mustache on a peachy flesh-colored ground; both are symbolic references to a Russian military man.

These identifiable objects and symbols are detached elements in an abstract geometric design of colored shapes, varied textures, and painted lines that includes paper collages with printed words, letters, the number 8, a postage stamp depicting the Czar, and a real thermometer. The collaged words are: opera (at the top), Thursday and tobacconist (in the middle), and (to the left) the name of a traditional academic painter, A. Vasnetzov, who had rejected Malevich’s paintings from exhibition. The words, like the represented forms, refer to things without clearly relating them to the other elements of the painting.

Zaum Realism

Reservist of the First Division uses fragments of objects, shapes, and words to communicate by non-rational means. This was a central technique of Russian Futurist writers that they called zaum, a neologism usually translated as “transrational.” Zaum entailed using non-referential linguistic forms — simple phonemes, letters, and nonsense words — to bypass rational understanding and communicate emotion directly. The Futurists believed that through zaum they were able to access a higher reality that transcended the limitations of rationality and the material world.

Malevich collaborated with the Futurist writers on several projects, the most important of which was the radically innovative opera Victory over the Sun (1913). Like the Futurists, he tried to use the formal elements of painting (line color, shape, composition, etc.) as direct means to communicate feeling independent of representation or obvious reference. He described many of his paintings, including Morning in the Village after Snowstorm (1912-13) and The Knife Grinder (1912-13), as “zaum realism.”

Kazimir Malevich, The Knife Grinder, 1912-13, oil on canvas, 79.5 x 79.5 cm (Yale University Art Gallery)

Russian Subjects

Although Malevich explicitly linked these two paintings to zaum’s direct emotional non-rational communication through basic formal units, they are less abstract and easier to decipher than the slightly later work Reservist of the First Division. Figures and space are simplified into geometric shapes and arranged to create repeating abstract patterns. The Knife Grinder depicts a man pumping a sharpening wheel as he works. His foot, hand, and knife appear in multiple positions to convey motion in time. Malevich derived the faceting of space and figure from techniques popular among many well-known Western European Cubists and Futurists whose works were reproduced in art magazines and exhibited in Russia.

Kazimir Malevich, Morning in the Village after Snowstorm, 1912-13, oil on canvas, 80 x 80 cm (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York)

The Italian Futurists often used modern representational techniques to depict conspicuously modern subjects. Malevich, by contrast, used an avant-garde formal vocabulary to represent traditional (even self-consciously “primitive”) subjects. Such subjects were popular among Russian avant-garde painters such as Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov, who promoted a specifically Russian approach to modernism by embracing Russian subjects and traditional art forms. Morning in the Village after Snowstorm shows Russian peasants carrying buckets and pulling a sled through a snowy village scene. The Knife Grinder uses his foot to pump a simple wheel and pulley mechanism, a marked contrast to the Italian Futurists’ passion for depicting electricity and powerful, sometimes violent, modern machines such as automobiles, trains, and machine guns.

Kazimir Malevich, Woman at a Poster Column, 1914, oil, collage and lace on canvas, 71 x 64 cm (Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam)

Combining Media and Styles

Malevich combined geometric abstraction, Cubist systems of representation, and collage in an unprecedented manner in Reservist of the First Division and related works such as Woman at a Poster Column (1914) and Composition with Mona Lisa (1914). With these works the zaum techniques of non-rational communication using basic formal units are more fully realized and developed to include recognizable images and objects detached from their usual context.

All three use large flat planes of color as a structuring device. These planes seem to hover in front of the picture plane, creating complex layers of space markedly different from the shallow, fractured pictorial space of most Cubist paintings. The inclusion of photographs and objects, such as the thermometer in Reservist of the First Division and the strips of lace in Woman at a Poster Column, was also an innovative zaum pictorial strategy that foreshadowed the Dada artists’ embrace of the illogical in their strategically disruptive use of collage.

Kazimir Malevich, Composition with Mona Lisa (Partial Eclipse), 1914, oil, graphite, and collage on canvas, 62.4 x 49.2 cm (State Russian Museum)

Replacing Conventions

Composition with Mona Lisa combines a collaged reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa with colored planes and suggestions of cylinders and other objects rendered in a Cubist style. The painted Russian text translates as “partial eclipse,” and the collaged newspaper text directly under the Mona Lisa reproduction declares “apartment for rent,” while the text collaged on the painted cube below reads, “in Moscow.” Two red ‘X’s have been painted on the Mona Lisa’s face and chest, and the top of her head is torn off. The work seems to thematize as well as embody the fact that the conventions of naturalistic representation, which had dominated Western art since the Renaissance, have been cancelled out. New replacements are available in Moscow, and Malevich puts himself at the forefront of the avant-garde.

Malevich’s intense engagement with Cubist and Futurist styles exemplified the Russian avant-garde’s adaptation of European modernist techniques to serve their own distinctive artistic aims — most notably the depiction of specifically Russian subjects. With his later collage works, Malevich ventured into new territory, combining abstract planes with representational elements. In the following year he would break away completely from representation and create a new art movement, Suprematism.

Additional resources:

Read more about Reservist of the First Division

Read more about Morning in the Village After a Snowstorm

Charlotte Douglas, Kazimir Malevich (New York: Harry Abrams, 1994).