Marianne Brandt, Kandem Bedside Table Lamp, 1928, lacquered steel, 23.5 x 18.4 cm (MoMA)

Chances are you have owned a lamp just like this one. It has no decoration or added “flair” that would distinguish it as being in the style of any particular designer, or even any particular decade. It appears absolutely generic — and yet it is the result of a very thoughtful design process in which each feature has been carefully considered.

The hood is long to protect the viewer from the glare of the raw bulb. A pin attaches the hood to the arm, allowing it to pivot slightly to direct the light. The wedge shape of the base helps in this regard as well, and provides ergonomic access to an obvious on-off switch. (How many times have you had to search to find the switch on a lamp?)

Its few, geometrically-regular parts are easy to manufacture and very efficient — notice the way the steel is rolled under at the opening of the hood to smooth the rough edge, as well as to provide additional rigidity. The lack of decoration keeps down manufacturing costs, but the proportions of the parts and the sheen on the curves of the lacquered steel are attractive in themselves.

Although it looks like it could have been made yesterday, this desk lamp was in fact designed in 1928 by a remarkable woman named Marianne Brandt at the Bauhaus, a famous design school in Germany. Brandt was exceptional not only as a designer, but also as a woman in the male-dominated field of metalwork.

Women at the Bauhaus

The charter of the Bauhaus stated that “any person of good repute, without regard to age or sex … will be admitted,” but when female applicants unexpectedly threatened to equal or even outnumber male applicants, the masters at the school agreed to limit their numbers and channel women exclusively into the pottery, bookbinding, and weaving workshops.[1]

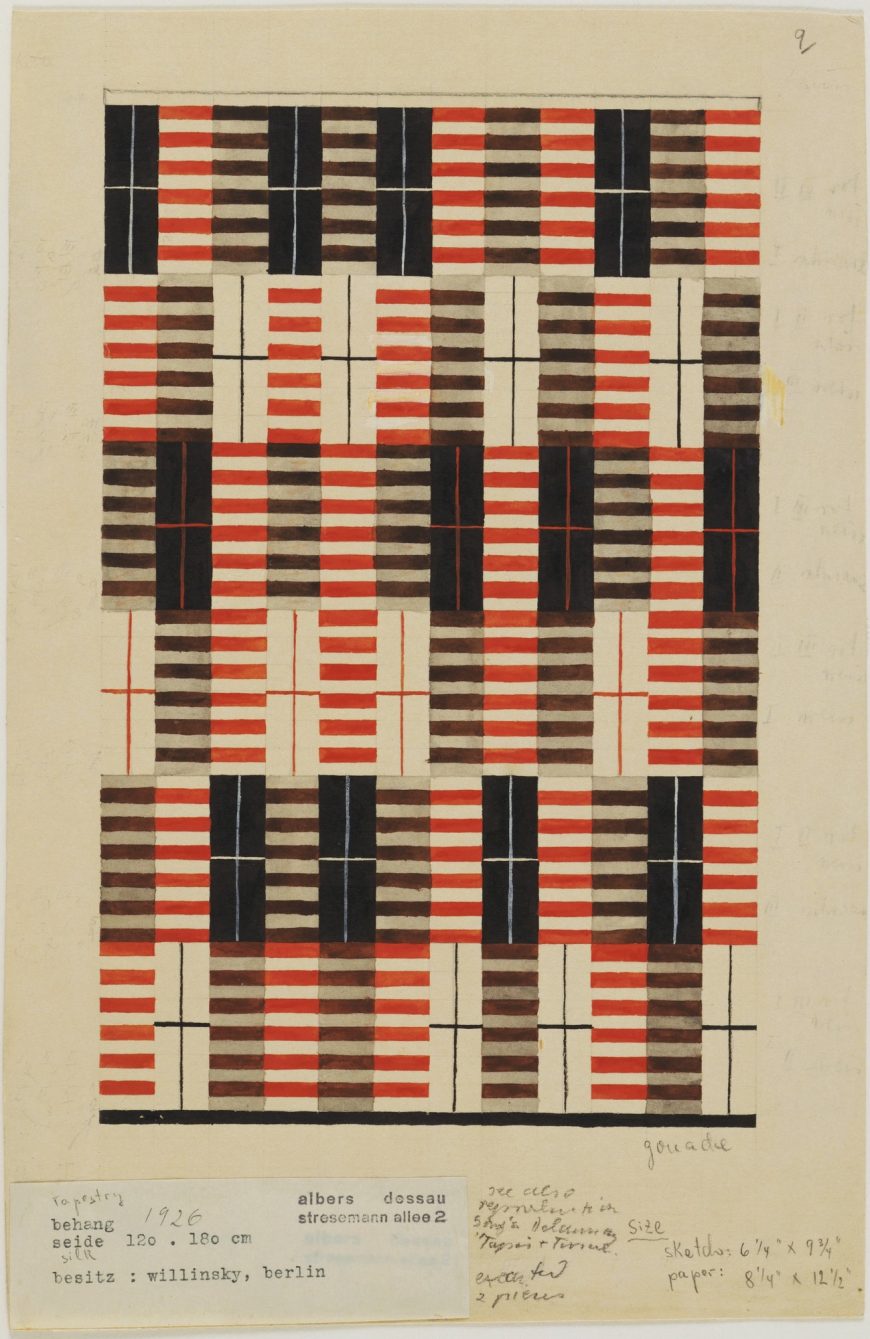

The pottery master resisted, and the bookbinding workshop was dissolved in 1922, so as a consequence almost all the women at the Bauhaus studied textiles such as weaving, embroidery, decorative edging, crocheting, sewing, and macrame. Anni Albers, for example, came to the Bauhaus in 1922 to study painting, but went into textiles instead, and by 1931 was appointed the head of the weaving workshop. When the Bauhaus closed in 1933, Albers emigrated to the United States, where she continued to teach. In 1949 Albers was the first female textile artist to have a solo show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

An exception to the rule

Brandt was an exception to this tendency to direct women into what were seen as gender-appropriate media. When she came to the Bauhaus in 1923, her work in the preliminary course caught the eye of the head of the metal workshop, László Moholy-Nagy, who made her his assistant. She designed the lighting fixtures for the new building when the Bauhaus moved to Dessau, and secured a number of important contracts with local manufacturers, helping to fund the school. When Moholy-Nagy left the Bauhaus in 1928, Brandt became acting director of the metal workshop before leaving the Bauhaus herself to work in industry.

Marianne Brandt, Ceiling Lamp, 1925, spun aluminum and milk glass shade, 105.4 x 38.1 cm (MoMA)

Key Bauhaus design principles

Brandt’s works exemplify the key principles of Bauhaus design: rationalism, functionalism, formalism, and design for manufacture:

Rationalism signifies the design of objects using a limited repertory of elementary shapes and colors. Geometric shapes such as circles, squares, cylinders, and cones, and primary colors and values such as red, yellow, blue, black, and white, are to be preferred wherever possible over more complex shapes and mixed colors.

Functionalism signifies a primary emphasis on making the object as easy and efficient as possible to use. “Pure” functionalism takes this creed to an extreme in which the design has no features that do not serve some necessary function: no merely decorative frills whatsoever, however attractive they may be.

Formalism signifies the use of materials in ways that suit their inherent properties: the transparency and brittleness of glass, the sheen and flexibility of metal, and so on. Ideally, those materials are to be left in their raw state and not disguised. Paint as a protective coat is permissible, but not giving plastic a fake wood veneer, for example.

Design for Manufacture takes into account how the object will be mass-produced by machines, and attempts to make that process as efficient as possible. Objects are designed with few (ideally modular) parts with simple shapes that can be produced and assembled easily and inexpensively.

Sometimes compromises were necessary. For example, rational shapes are not always the most functional or ergonomic, and in such cases functionalism tended to override other principles. The Bauhaus is thus associated primarily with functionalism in design.

A tea set for the machine age

George Christian Gebelein, Five-Piece Coffee and Tea Service, 1929, silver and ebony wood (MFA Boston)

To see how these design principles work in practice, we can compare a Marianne Brandt tea pot with a roughly contemporaneous one by George Christian Gebelein. The biggest difference is the amount of added decoration in the Gebelein, most obviously the fluting (vertical grooves) and engraved designs that serve no functional purpose but would considerably increase the difficulty, time, and hence expense of manufacture. By contrast, Brandt’s teapot — a handmade model for a design intended for manufacture — is made of as few parts as possible, and all of those parts are reduced to simple, rational forms.

Marianne Brandt, Tea Pot, 1924, nickel silver and ebony (photo: Sailko, CC BY 3.0)

It is largely a study in circles: the overall hemispheric shape of the body is complemented by a circular opening and a half-circular handle. The strainer insert (not shown here) is similarly a cylinder with a hemispherical base, topped with a circular rim, and its handle is a perfect half-circle with an inset half-circle thumb grip. These simple shapes are not only easy to manufacture, their repetition gives an overall harmony to the work.

If we look closely, though, within this highly rationalized, geometric design there are a number of subtle choices. The spout is not a perfect circle, since that would cause the pot to dribble, so a slight lip helps to project the tea when it is poured. This is an example of functionalism superseding rationalism.

Similarly, notice that the fill opening is offset towards the back of the pot, and the handle is similarly not centered. This unexpected asymmetry seems capricious, but in fact it prevents the tea from sloshing out of the lid when it pours, and helps to keep the center of gravity consistent in the pot as it is tilted. Notice that the ebony wood handle — a material chosen for the handle and lid knob because it does not conduct heat — is similarly set backwards to prompt the user to grip it appropriately.

Marianne Brandt, Tea Infuser and strainer, 1924, Silver and ebony wood, 8.3 x 10.8 x 16.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Design experimentation

Another mock-up of the tea infuser design shows some slightly different balances among the principles of rationalism, functionalism, and design for manufacture. Here, the hinged handle has been replaced by a half-disk of ebony wood attached to the side with flanges. This design is simpler, and has the benefit of keeping the handle from getting in the way when filling the pot and accessing the infuser. Brandt probably tested this option because it would be easier and cheaper to manufacture.

This version of the tea pot would not, however, be as easy to hold and pour. Considerable grip strength would be required to pinch the wooden handle securely, especially when the kettle was full of water, and the weight would not be evenly balanced throughout the pour. This comparison does show that, while the Bauhaus principles were not conducive to stylistic flair or personal expression on the part of the designer, a good deal of thoughtful attention did go into their apparently obvious, generic designs.

Notes:

- Sigrid Wortmann Wellige. Women’s Work: Textile art from the Bauhaus (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1993), pp. 41-42.

Additional resources:

Bauhaus: Building the New Artist at the Getty Research Institute

Magdalena Droste, Bauhaus: 1919-1933 (Köln: Taschen, 2006).

Sigrid Wortmann Wellige, Women’s Work: Textile art from the Bauhaus (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1993).