Yvonne Rainer, We Shall Run, 1963 performed March 7, 1965 at the Wadsworth Atheneum (photo: Peter Moore, © Barbara Moore); left to right: Robert Rauschenberg (obscured), Sally Gross, Joseph Schlichter (obscured), Tony Holder, Deborah Hay, Yvonne Rainer, Alex Hay, Robert Morris (obscured), and Lucinda Childs

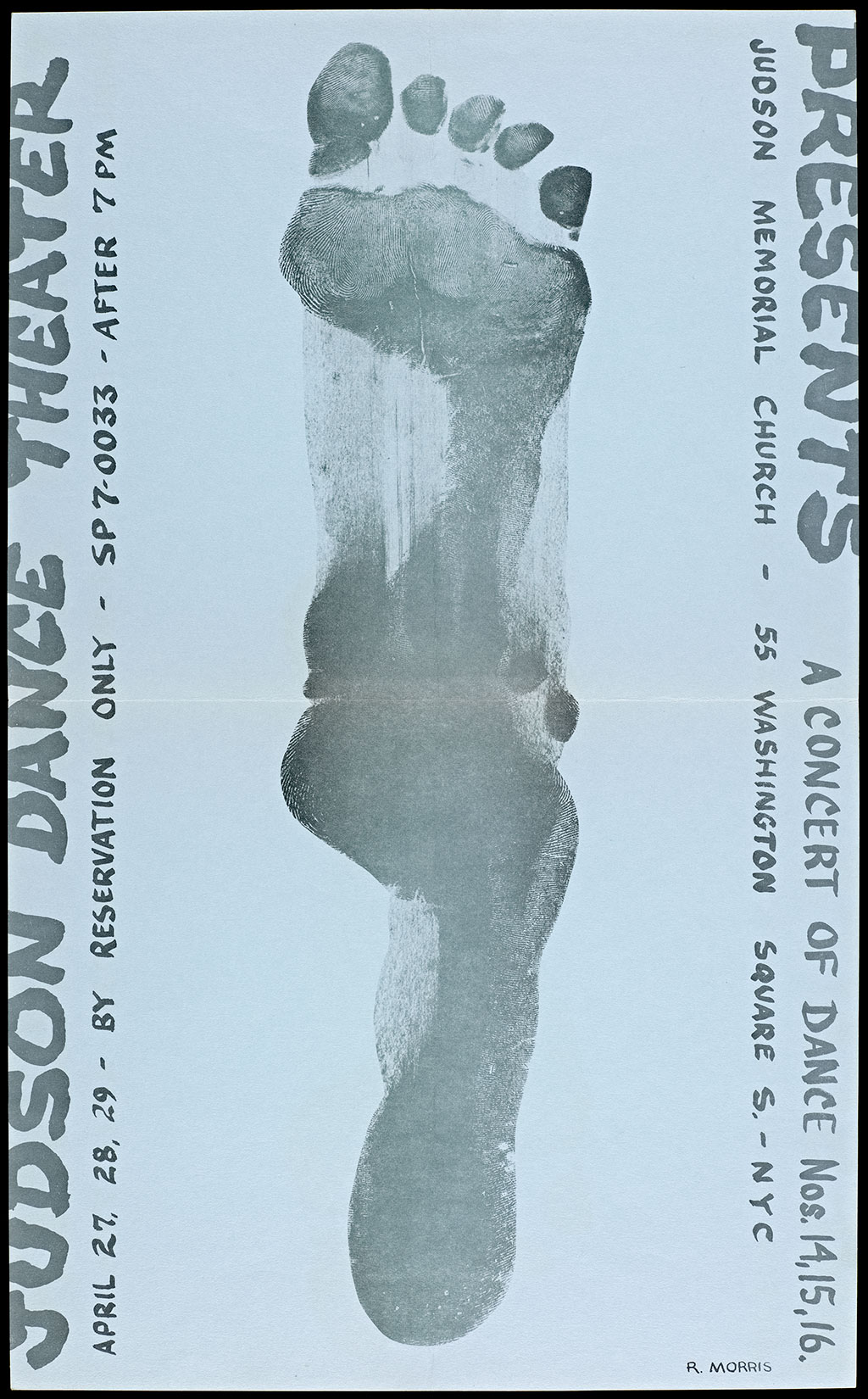

Robert Morris, “A Concert of Dance Nos. 14, 15, 16,” Judson Memorial Church, 1964, offset on paper (Getty Research Institute, © Robert Morris)

We Shall Run

Twelve performers stand still onstage. A minute passes, then another. You sit there watching, waiting for the dancing to begin. After what feels like an interminable period of stillness, the performers take off at a brisk jog. They form packs, crisscross the stage, peel off, and then rejoin the group. You make out the sound of sneakers squeaking on the floor under the booming, dramatic climax of Hector Berlioz’s Requiem played on the loudspeaker. If there is a pattern here, it evades you. But you watch as the joggers, like synchronized swimmers, merge, swerve, and break off from the group. Occasionally, you will zero in on a single performer. One woman jogs assuredly, her straight spine and intense gaze hint at her dance background. Meanwhile, another performer is getting visibly tired; they have been running for a while. This brisk jogging is the centerpiece of Yvonne Rainer’s We Shall Run (1963), the opening piece of the Judson Dance Theater’s “A Concert of Dance #3.”

The group was so-named for their primary performance space located across the street from Washington Square Park in the historically progressive Judson Memorial Church. Here, the Judson Dance Theater redefined dance as movement and formed a link between the worlds of visual art, music, theater, and film beginning in the early 1960s.

Stanford White, Judson Memorial Church, 1888–96 (photo: Rachel Moore, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

What is post-modern dance?

The choreographers and performers associated with Judson participated in a series of concerts and workshops between 1962 and 1964 and defined the criteria for what is typically called post-modern dance. Post-modern dance, like postmodernism in architecture or visual art, refers to a period of avant-garde activity responding to, and reacting against, the orthodoxies of modernism. This means that in order to understand post-modern dance, we must turn briefly to modern dance.

Isadora Duncan, Long Beach, California, 1917 (photo: Arnold Genthe)

The earlier generations associated with modern dance (Isadora Duncan, Martha Graham, and others) had moved away from ballet, or classical dance, and its precise, disciplined vocabulary towards an understanding of dance as authentic, spiritual expression. By the 1960s, however, this expressive version of dance no longer seemed relevant. The Judson Dance Theater emerged as a group of artists seeking to challenge the status quo and re-imagine avant-garde dance for a new generation. In the place of the spiritual and psychological, they celebrated improvisation, the unidealized physical body, and everyday movements.

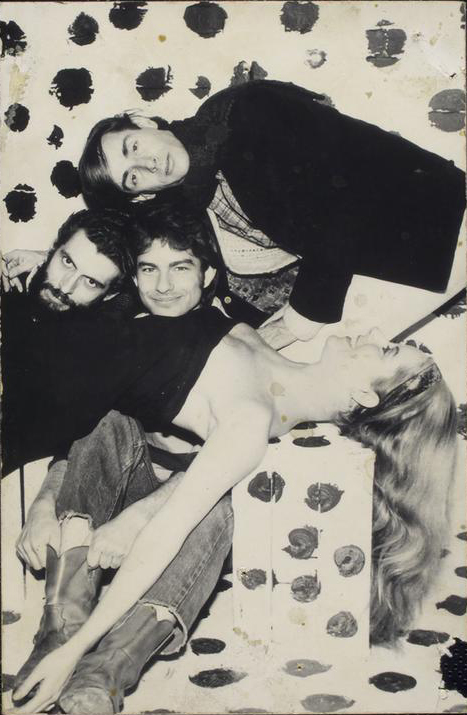

Promotional photo for dance performance at Judson Memorial Church, 1967, James Waring (top), Charles Stanley (with beard), Peter Hartman, and Deborah Lee (photo: © James Gossage, The New York Public Library)

The Judson Dance Theater began with a series of composition workshops led by Robert Dunn in Merce Cunningham’s studio space at 530 Sixth Avenue in Manhattan (Merce Cunningham was one of the leading avant-garde choreographers of the 20th century). Many of the Judson Dance Theater participants were members of the Cunningham Company. Through these workshops, Dunn translated and tested the relevance of composer John Cage’s use of chance but in a choreographic context.

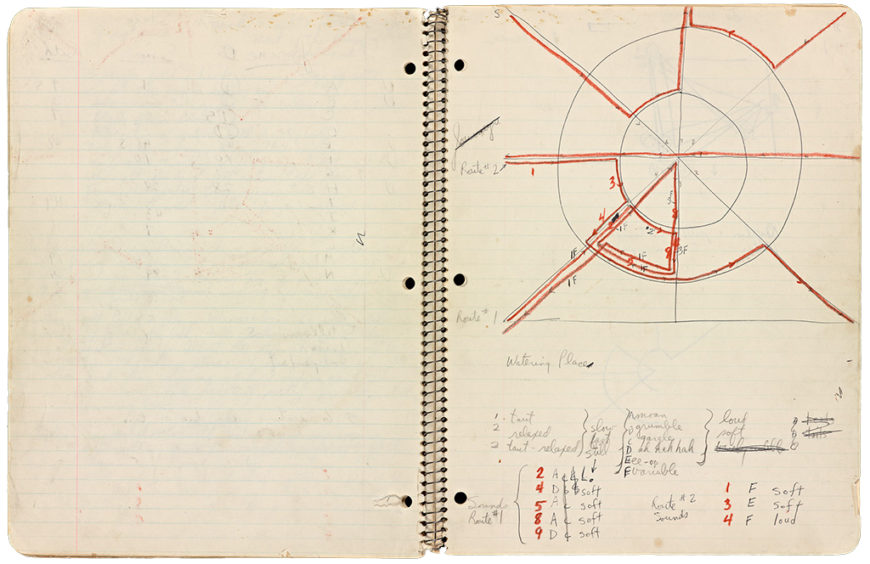

Cage innovated the use of chance in musical composition in the United States. Unlike the Surrealist automatic drawing or other versions of chance composition, Cage’s version of chance, termed indeterminacy, involves carefully scored compositions that invited chance to impact performance in unexpected ways. Cage used indeterminacy to disrupt the artist’s control over musical performance and to re-imagine noise as music. In the Dunn workshops, indeterminacy and ambient noise was translated into improvised and everyday movement.

Cage, via Dunn, was one of the three primary influences for the Judson group. Many of the workshop participants had also studied with the postmodern dance pioneer, Anna Halprin on the West Coast. Halprin’s teaching emphasized the physicality of the body and improvisation. A number of the choreographers who attended the Dunn workshops also studied and danced with James Waring, whose interdisciplinary approach to composition synthesized movement drawn from classical, modern, and even popular dance (just as a visual artist might gather found images together in a collage). Drawing on these influences, the Judson choreographers explored methods like improvisation and choreographic scoring techniques that, like Dada collage, privileged chance.

Judson and Minimalism

Yvonne Rainer wrote simple instructions for making Minimalist work which she titled “A Quasi-Survey of Some ‘Minimalist’ Tendencies in the Quantitatively Minimal Dance Activity Midst the Plethora, or an Analysis of Trio A.” Want to make a Minimalist object? Follow the chart and simply substitute “illusionism” for what she calls “literalness.” Are you making a dance? Replace the narrative arc of “development and climax” with “repetition.” Minimalist artists often used repetition to create logic and structure within a work of art.

Minimalism was also called “Primary Structures” and “ABC art” in its earlier years because it was so matter-of-fact. Minimalism sought to present forms in space that were simply expressive of themselves without reliance on any external reference or meaning. This art wasn’t meant to draw on literary references or cultural symbolism. Its own internal logic was enough.

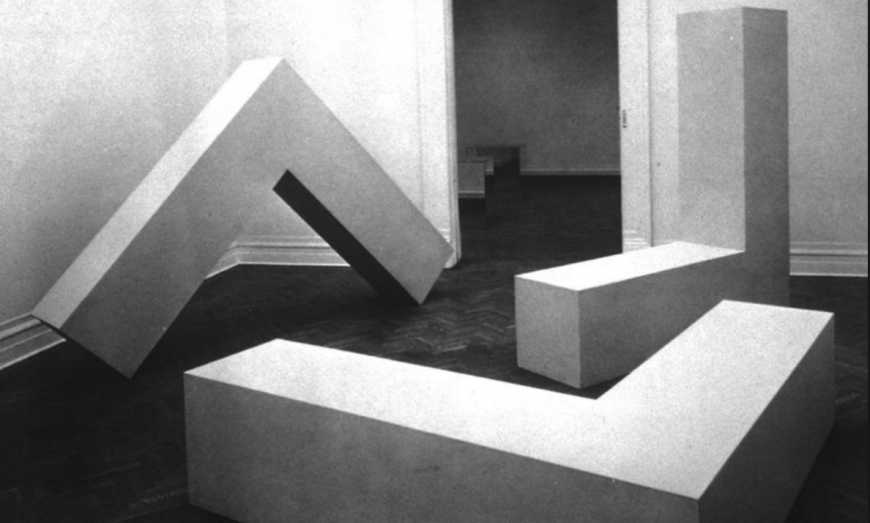

In the Robert Morris sculpture, Untitled L-Beams, each of the three L-beams are identical, repeating the same form in space though at such differing angles they make us doubt their uniformity. Like Morris, Rainer offers a simple enough formula, but her document’s verbose title renders the purported procedure tongue-in-cheek. Rainer has a sense of humor. As the booming Berlioz sound track for the somewhat comic We Shall Run, assures us, there is room for both grandeur and levity in post-modern dance.

Robert Morris, Untitled (L-Beams), 1965, originally plywood, later versions made in fiberglass and stainless steel, 8 x 8 x 2′

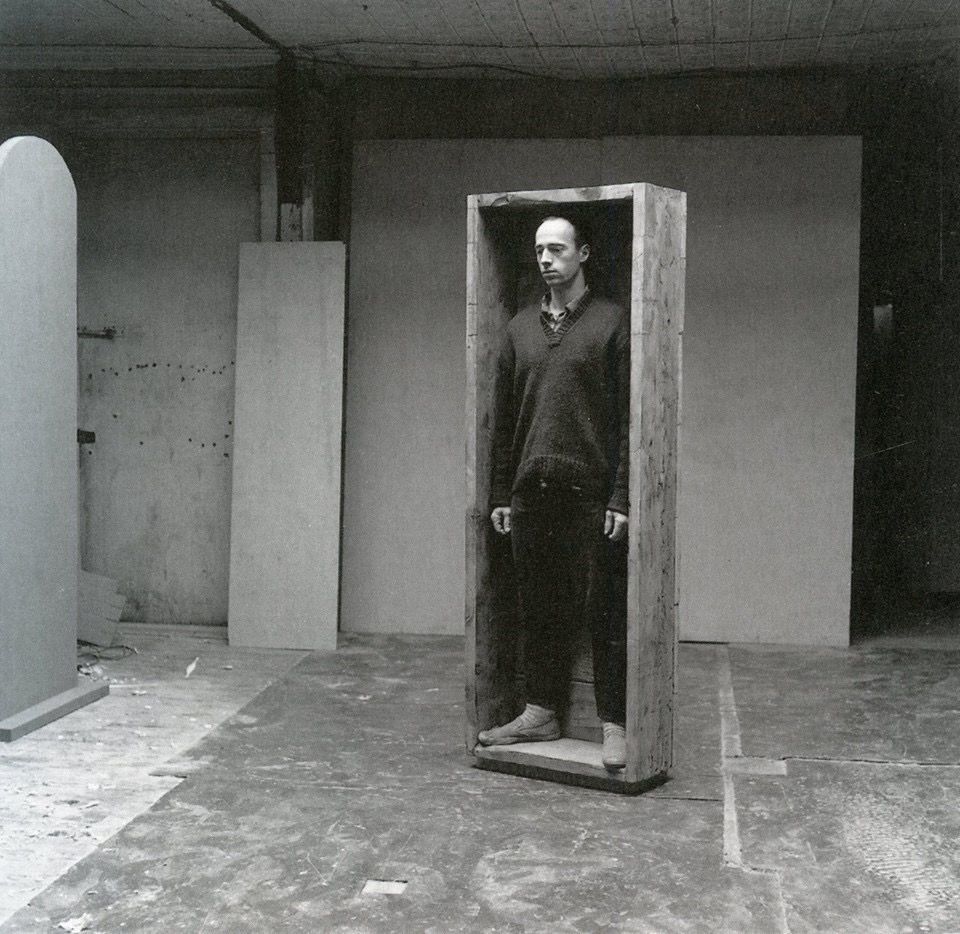

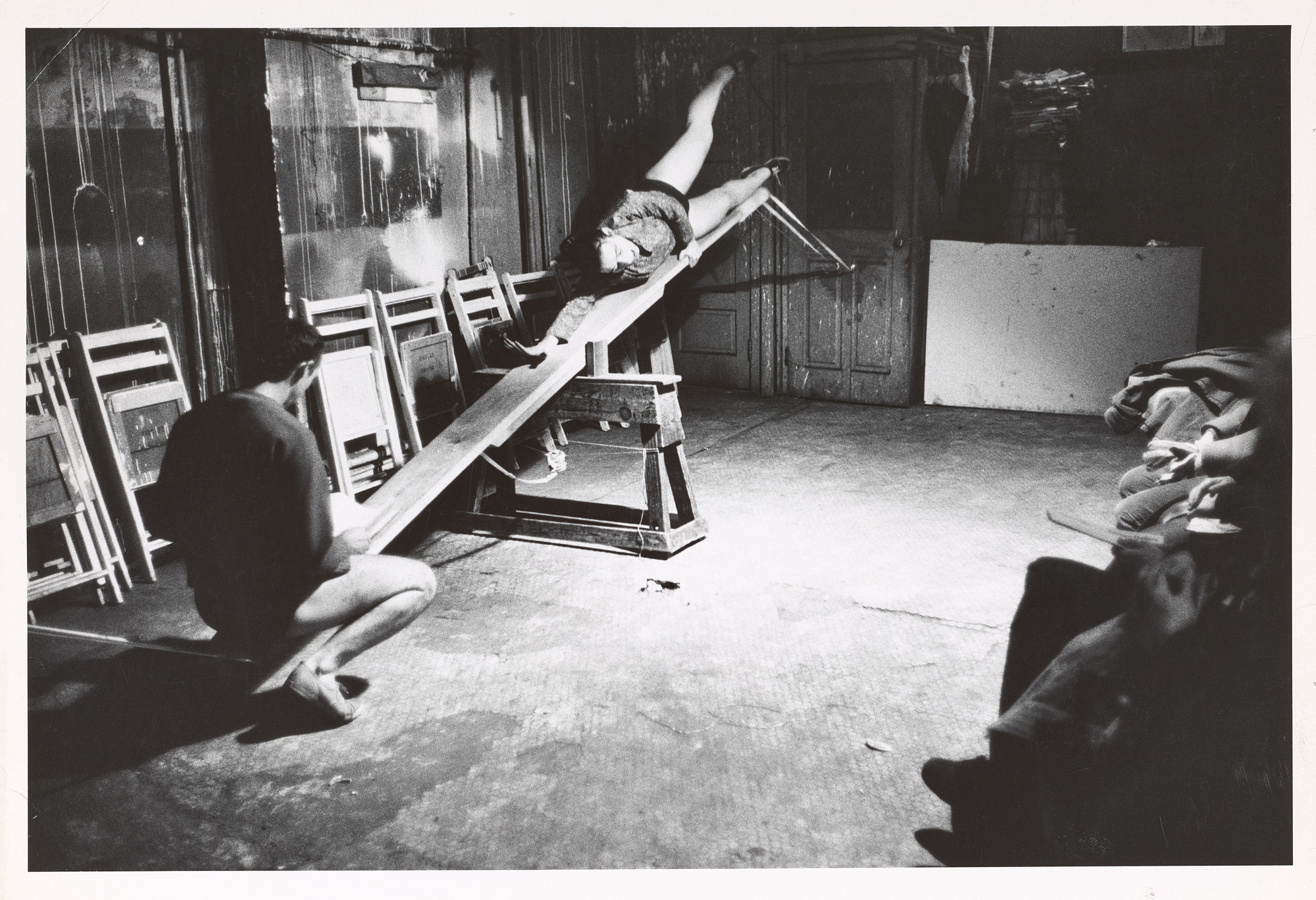

Rainer’s “Quasi-Survey,” points to the strong relationship between Minimalism in the visual arts and the choreography coming out of Judson. Like the Minimalist sculptors, the Judson group avoided psychological depth, narrative convention, and illusionism in favor of Minimalism’s interest in literal presence. Sculptor Robert Morris first began to make the simple geometric forms that he became for known for, as props for the dances created by his partner Simone Forti.

Through the influence of Forti and Rainer and his attendance of the Halprin and Dunn workshops, Morris developed his reduced geometric vocabulary as a part of his dance-based explorations of the physicality and the dimensional form of the human body.

Simone Forti, “See Saw” 1960 with Yvonne Rainer and Robert Morris (photo: © Robert R. McElroy, Getty Research Institute)

Just as the investigation of objects in space propelled Morris’s early Minimalist installations, similarly, other Judson performers were propelled by the analytic investigation of movement. As Rainer’s flair for grandeur suggests, the Judson group was not all about reductive Minimalism. Rather, the members of the Judson Dance Theater fall loosely into three camps: reductive, theatrical, and multimedia. The theatrical strand of the Judson project is best represented by the work of two other dancers, David Gordon and Fred Herko.

Judson in Greenwich Village

More than a series of concerts and workshops, the Judson Dance Theater was a dense web of individuals, social interactions, and interdisciplinary collaborations that touched many of the most influential facets of artistic activity in 1960s Greenwich Village. Just as Judson members danced with Merce Cunningham, acted in productions by the American Poets Theater, and starred in Warhol films, so they called on poets, artists, and musicians to collaborate in their concerts of dance.

Greenwich Village in the early sixties was animated by a deeply shared sense of the potential of avant-garde innovation and efforts to erase boundaries between disciplines. In this milieu, artists like Morris or Rauschenberg could become not just sculptors and painters but performers, choreographers, and filmmakers. The experimental spirit of the concerts at Judson Memorial Church offered sites for interdisciplinary collaboration. As one of his contributions to the first Concert of Dance, Judson choreographer Fred Herko collaborated with legendary jazz musician Cecil Taylor; the two simultaneously improvised, riffing on each other in their chosen media.

The Judson Dance Theater was a collaborative, interdisciplinary constellation of workshops, concerts, and individuals that radically expanded our understanding of what dance could be. Dance, the Judson work argues, is not only a ballerina’s grand jetés and fouetté turns or Martha Graham’s angst-ridden contractions but also, running in sneakers.

Additional resources:

Judson Dance Theater: The Work is Never Done. New York: MoMA, 2018

Sally Banes, Democracy’s Body: Judson Dance Theater 1962 – 1964 (Durham: Duke University Press, 1993)

Ramsay Burt, Judson Dance Theater: Performative Traces (London and New York: Routledge, 2006)