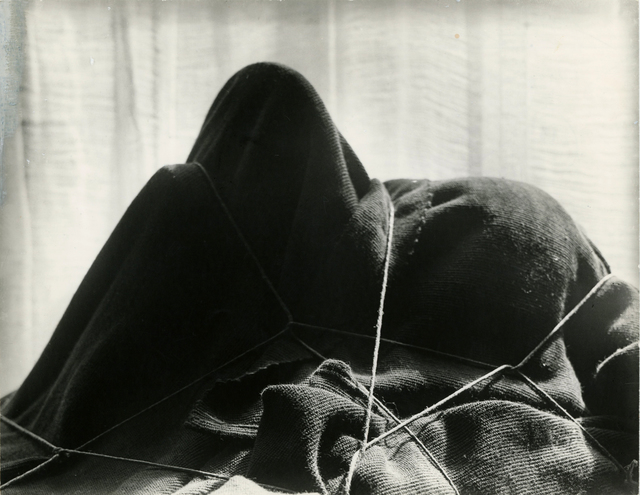

An enigmatic image

Man Ray’s photograph of a mysterious object or objects covered in a blanket and tied up with rope is the opening image of the Surrealists’ first journal, La Révolution Surréaliste. It appeared without caption or attribution in the middle of an essay announcing the Surrealists’ dedication to dreams and revolution. Readers were left to determine its significance on their own. Perhaps it was intended to represent the mysteries of the unconscious bound up and hidden beneath the surface of ordinary things. Perhaps it referred to the as-yet-undisclosed contents of the magazine that the reader would encounter in the following pages.

Most likely it was intended to appeal to the unconscious desires of each individual reader. Surrealism as a movement was dedicated to creating works that not only expressed their author’s unconscious mental activity, but also provoked such activity in the viewer. The Surrealists developed a number of tools for achieving this end, including irrational juxtapositions, suggestion, and subversive realism, all of which were mobilized in Surrealist photography.

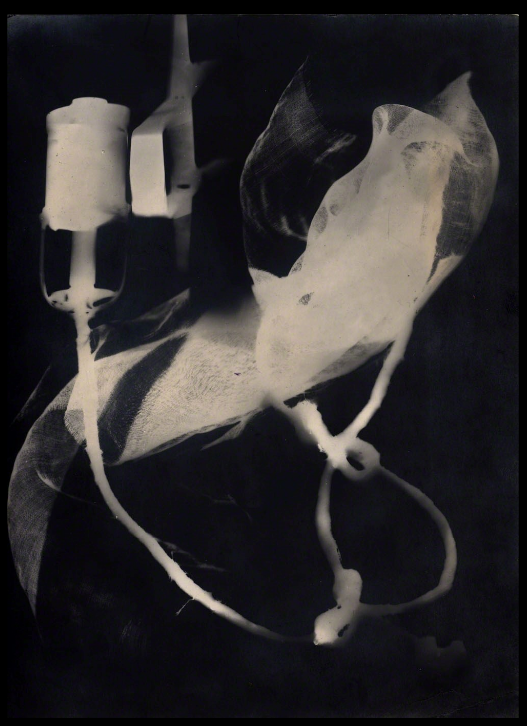

Rayographs

Photography played an important role in Surrealism from the movement’s inception. The New York Dadaist Man Ray moved to Paris in the 1920s and became an early member of the Surrealist group as well as working as a successful fashion photographer. The Surrealist leader André Breton admired his Dada rayographs for the surprising ways they both revealed and transformed common objects. Rayographs, also known as rayograms or photograms, are made by placing objects on photo-sensitive paper and briefly exposing them to light. The silhouettes of the objects are recorded on the paper as white unexposed areas, and can create unexpected patterns and suggestive images.

Photographic proof

Man Ray’s photographs liberally illustrate Surrealist journals, as do many photographs from anonymous sources. In many instances these photographs were intended as visual proof of Surrealism’s existence in the world. Traditionally regarded as a means to create factual visual records, photographs were used by the Surrealists both to document Surrealist occurrences and to call into question the nature of reality.

During early debates on the possibility of a Surrealist visual art, Pierre Naville published a statement that the only acceptable types of visual production were non-artistic photographs that revealed the Surrealist nature of reality. Although this restrictive view of Surrealist art did not prevail, interest in photography as a form of Surrealist documentation endured and became an important aspect of Surrealist visual production.

Breton’s autobiographical texts Nadja and L’Amour fou were illustrated with photographs by Man Ray, Brassaï, Boiffard, and others. The photographs document the objects and Paris locations described in Breton’s narrative. They are presented as a form of evidence that implicitly attests to the truth of Breton’s description of his Surrealist adventures.

Man Ray’s photographs of fashionable hats and Brassaï’s photographs of discarded bus tickets were used to illustrate Surrealist essays on the widespread presence of erotic forms and automatism in daily life. The photographs were intended to document how the common objects of the modern world are profoundly shaped by unconscious, frequently sexual, desires. Women’s hats take on phallic and vaginal forms, while the tickets and other odds and ends people drop on the street have been folded and fondled into elaborate and suggestive shapes.

The Surrealists called these manipulated objects involuntary sculptures and, like doodles and Surrealist artworks created by using automatic techniques, they understood them to be the direct result of unconscious creative activity.

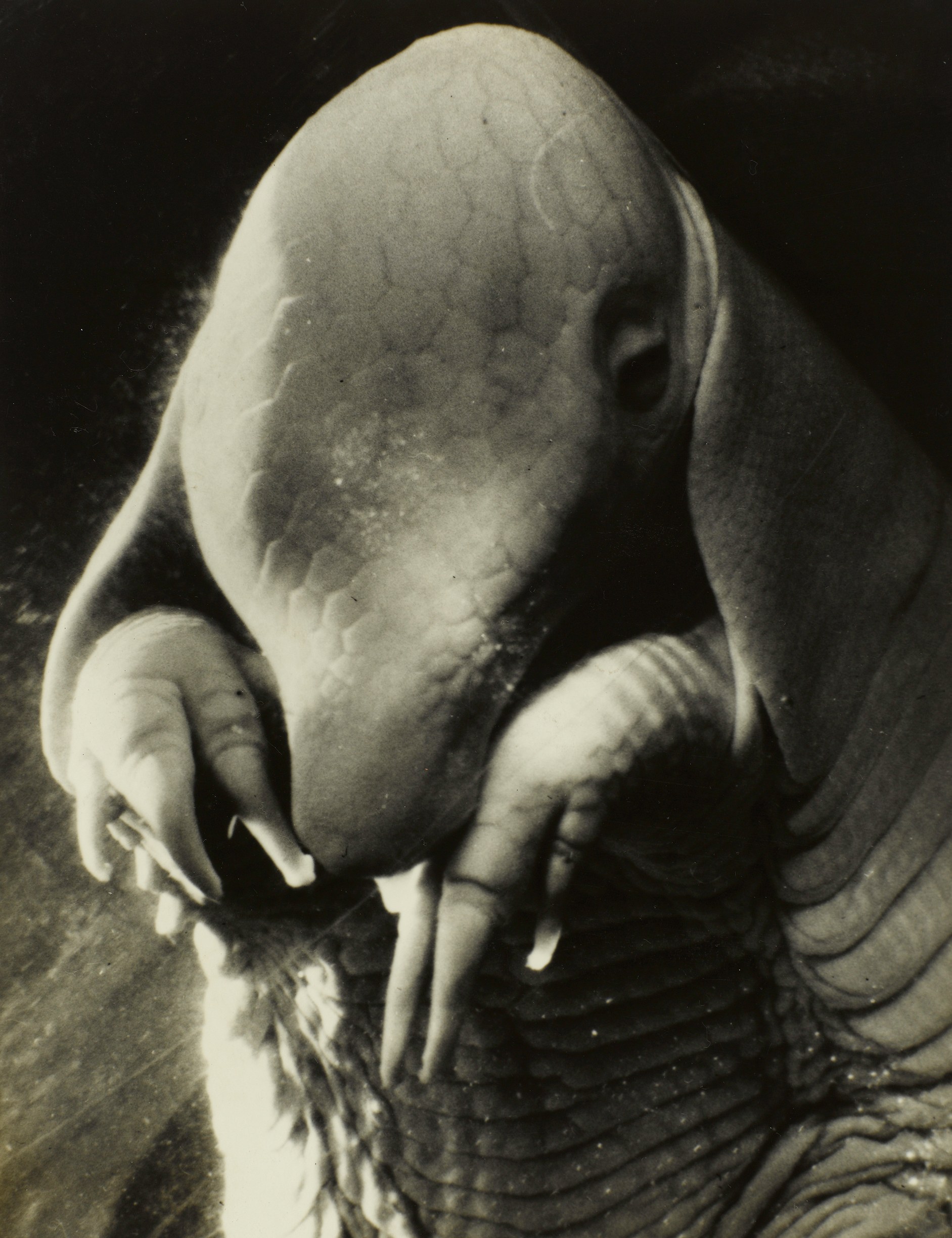

The strangeness of the world

Surrealist photographs were also used to reveal the strangeness of the world we think we know, often by simply presenting it in a new way. Dora Maar titled her photograph of a baby armadillo after the anti-hero of Alfred Jarry’s famously transgressive and iconoclastic play Ubu Roi (1896), which was much admired by the Surrealists.

The close-up image of the animal’s unfamiliar form is startling in itself, but by connecting the armadillo to Père Ubu, Maar created an emotional resonance for viewers familiar with the character. Suddenly, the small animal is transformed into a large, greedy, and violent human being — what was perhaps merely strange becomes monstrous. This is possible in part because of the way the photograph distorts our sense of scale by close-cropping and isolating the animal within the frame.

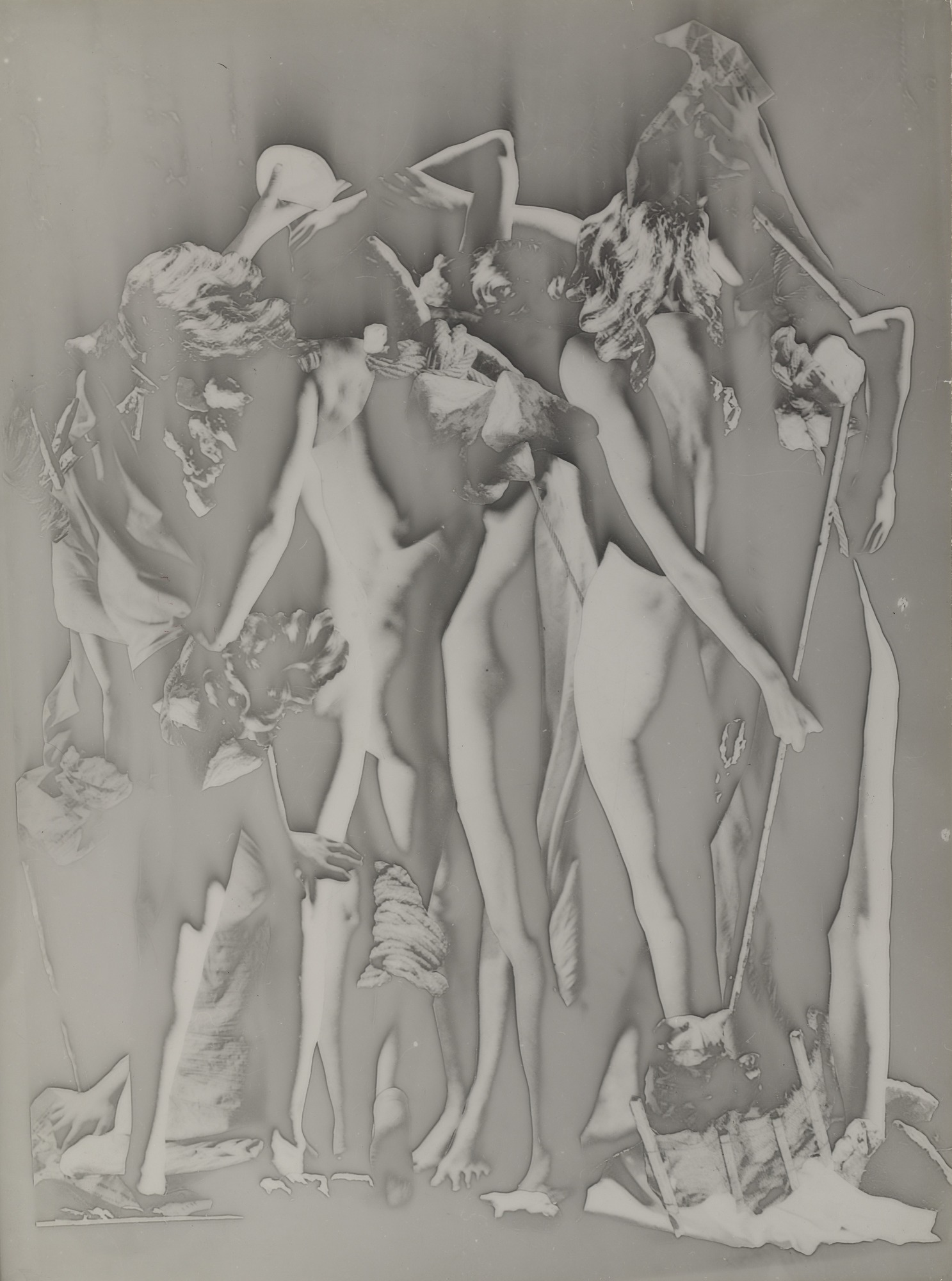

Innovative techniques

In addition to presenting photographs as Surrealist documents of the unexpected strangeness of reality, photographers associated with Surrealism experimented with darkroom techniques to create bizarre, often unpredictable, results.

In works such as The Secret Gathering, Raoul Ubac exploited the unsettling effects of double exposures and solarization (extreme over-exposure of film, which reverses tones) to suggest photography’s capacity to reveal a Surrealist reality hidden from ordinary vision. Based on photographs of two nude women, Ubac used darkroom manipulations to transform the original photographs into the suggestion of an other-worldly gathering of semi-human beings. Because we can still see some body parts clearly, we are led to think that this strange photograph may be a faithful document of a surreal world.

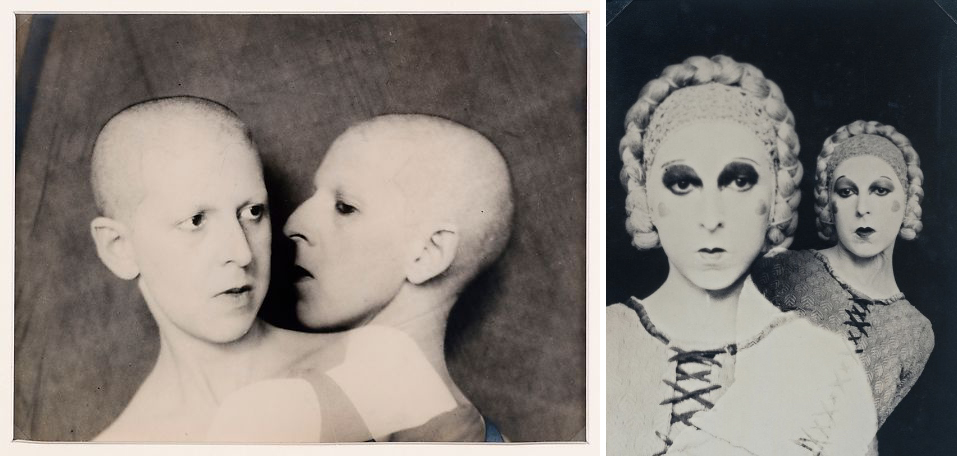

Left: Claude Cahun, Que me veux tu? 1929, gelatin silver print (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York); Right: Claude Cahun, Self-Portrait, 1929, gelatin silver print (Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris)

In Que me veux tu? (What do you want from me?) Claude Cahun similarly used darkroom manipulation to present herself doubled. Cahun’s self-portraits use multiple exposures, costumes and varied strategies of self-presentation to question the nature of individual identity. Her photographs are unusual in the context of Surrealist photography both as self-portraits and as images of a woman made by a woman.

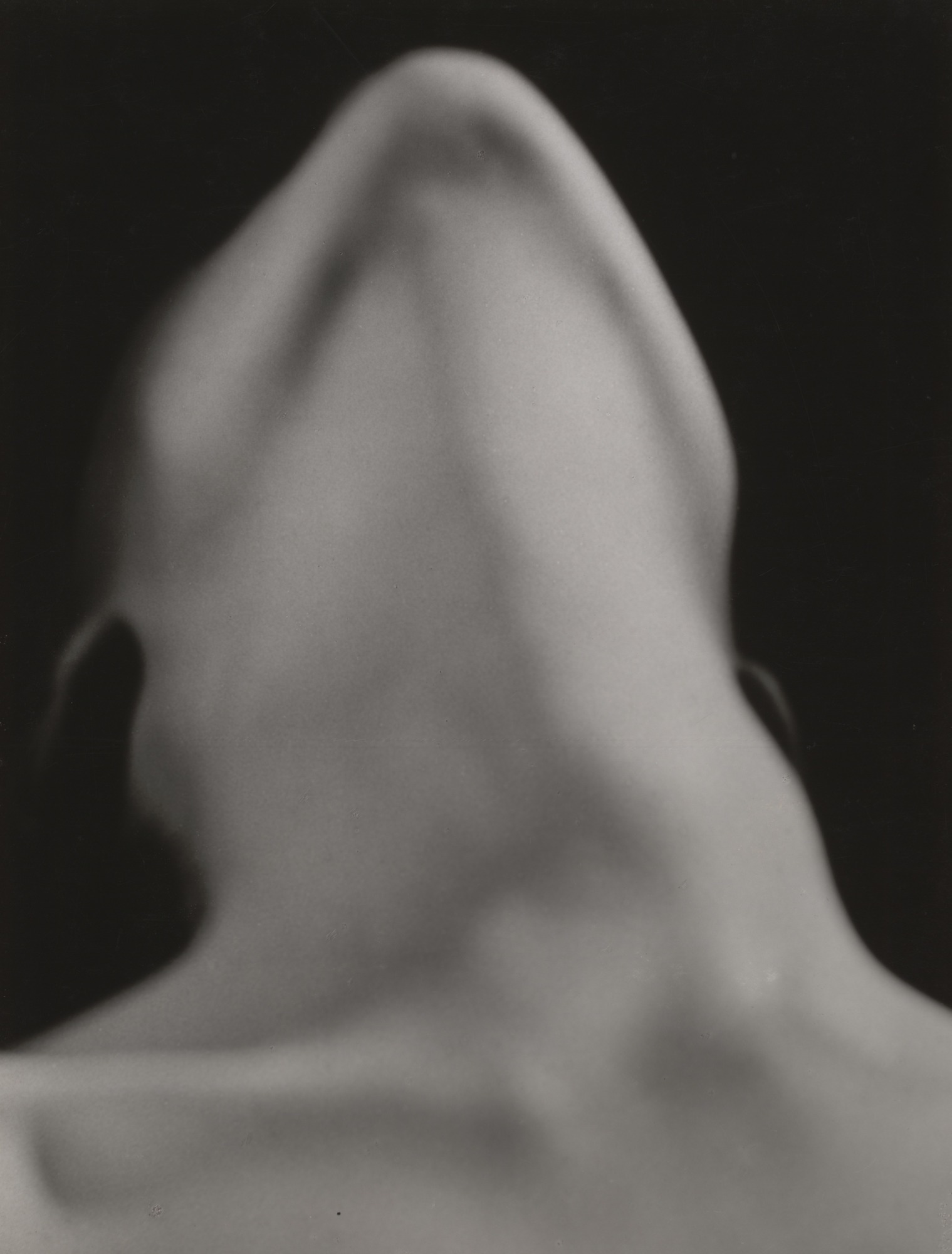

Women’s bodies were a favored subject for Surrealist photographers. Employing unusual angles, cropping, distorting lenses, and selective focus, Surrealist photographers transformed the body according to their desires and imagination. The infinitely malleable forms of the body served as revelatory means for Surrealist vision. Man Ray’s Anatomies, for example, transforms a woman’s chin and neck into a phallic form, in keeping with Freudian theories of fetishism.

Hans Bellmer combined sculpture with photography in the creation of his doll, whose body changed with each image, fragmenting and multiplying body parts according to the erotic desires of its maker.

Photography and film as Surrealist media

Some scholars consider photography to be the most effective of the Surrealists’ visual productions in part because of its ability to reveal hidden realities and to demonstrate the transformative powers of vision. In addition, photography is less restricted by the expectations and artistic conventions that affect the traditional art forms of painting and sculpture.

Film also seems to be a particularly appropriate Surrealist medium, as was noted in the first published discussion of the possibilities for Surrealist visual art. The Surrealists recognized that film could literally show the flow of unconscious thought and create extended dream-like visual experiences. During the Dada period the group made a practice of moving from theater to theater, watching only parts of the films being screened. In this way they experienced the unfolding of a suggestive collection of disparate images without submitting to the logic of a single narrative.

Luis Buñuel was the most dedicated and successful Surrealist filmmaker. Salvador Dalí collaborated with him in the creation of the two most important and notorious Surrealist films, Un Chien andalou (1929) and L’Age d’Or (1930). While film never became the primary focus of Surrealist visual production, the influence of Surrealism on photography and filmmaking has been immense and endures to the present day.

Additional resources:

Read more about Man Ray at MoMA

See all of the Rayograms from Champs Délicieux at the J. Paul Getty Museum