The 1912 art book Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) was originally intended to be a yearly “almanac” published by a Munich-based artists’ collective of the same name. It is a fascinating document of the early-twentieth century Expressionist art scene, featuring a dozen essays on topics ranging from so-called primitive masks to the stage direction for an experimental “color-tone drama” called The Yellow Sound. Particularly interesting is the eclectic variety of its illustrations, which combine the work of modern artists such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, and Pablo Picasso with African statues, Chinese ink painting, German folk art, Renaissance woodcuts, and Medieval sculpture.

An inner Renaissance

One of the editors of the book, the Russian artist Vasily Kandinsky, wrote of Der Blaue Reiter’s intent, “We aim to show by means of the variety of forms represented how the inner wishes of the artist are embodied.” [1] This emphasis on the “inner” or subjective mental states of the artist, as opposed to the “outer” or objective experience of nature, is a central theme of Expressionist art theory.

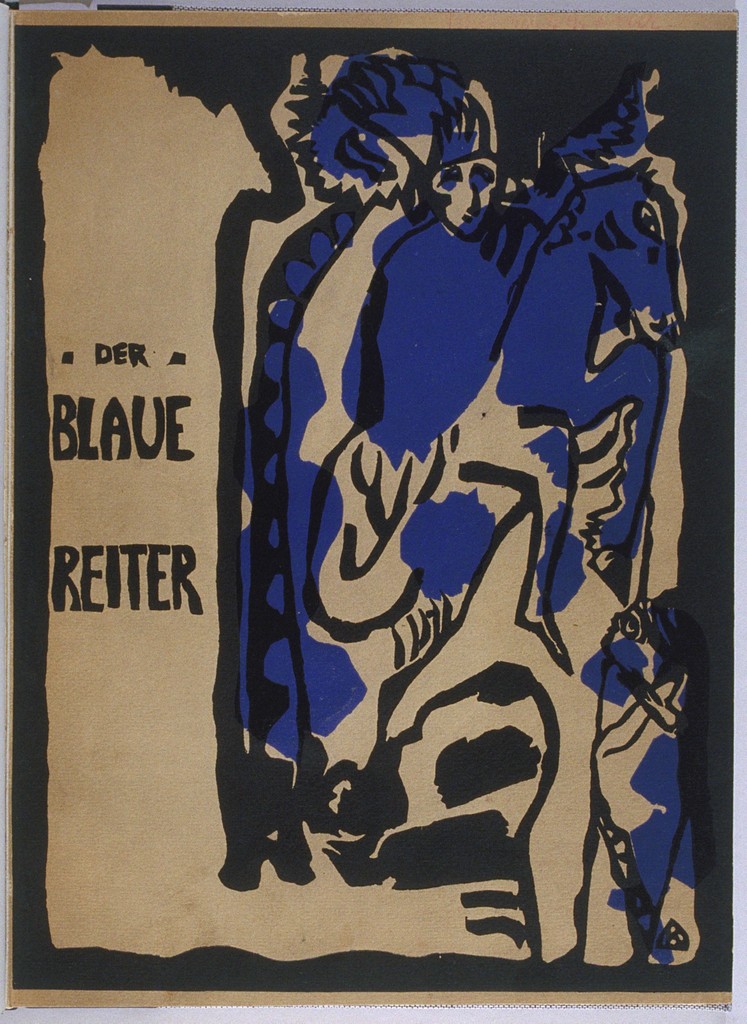

In a preface to the group’s first exhibition, Kandinsky similarly detects in his fellow artists “the signs of a new inner Renaissance.”[2] The word “inner” distinguishes this new Renaissance from the Italian Renaissance of the 1400s, which saw the rise of a naturalistic style of representation that, many Expressionist artists contended, was only concerned with representing the outer appearances of material reality. The crude, almost childlike simplicity of the cover art for the Almanac, along with its Christian medieval imagery of the blue rider as Saint George, is a visual emblem of two of the groups’ main themes that will be explored here: primitivism and spirituality.

An artists’ collective

The members of the Blaue Reiter group, including Gabriele Münter, Franz Marc, Auguste Macke, Vasily Kandinsky, and Alexej von Jawlensky, banded together because they felt that the art establishment had shut them out of opportunities. In the modern period, like-minded artists would often form such cooperatives to sponsor their own exhibitions free from conservative art juries, as well as to provide for mutual support and the exchange of ideas. Among the art movements that got their start in this way were the Impressionists, the Vienna Secession, the Fauves, and another German Expressionist group, Die Brücke.

The name Der Blaue Reiter, as Kandinsky later somewhat flippantly suggested, was chosen because fellow artist Franz Marc liked horses and Kandinsky liked riders, and they both liked the color blue. The group’s emblem was the Roman Christian soldier Saint George, who slew a dragon that was demanding human sacrifices.

The figure of the Blue Rider thus embodied the spiritual focus of the group as well as their belief that art plays an important social role in the struggle between good and evil. The intensified color and simple, almost childlike rendering of the same story by Auguste Macke is characteristic of the group’s style, although as Kandinsky noted above, they recognized the great variety of ways in which “inner” states could be expressed.

Primitivism and spirituality

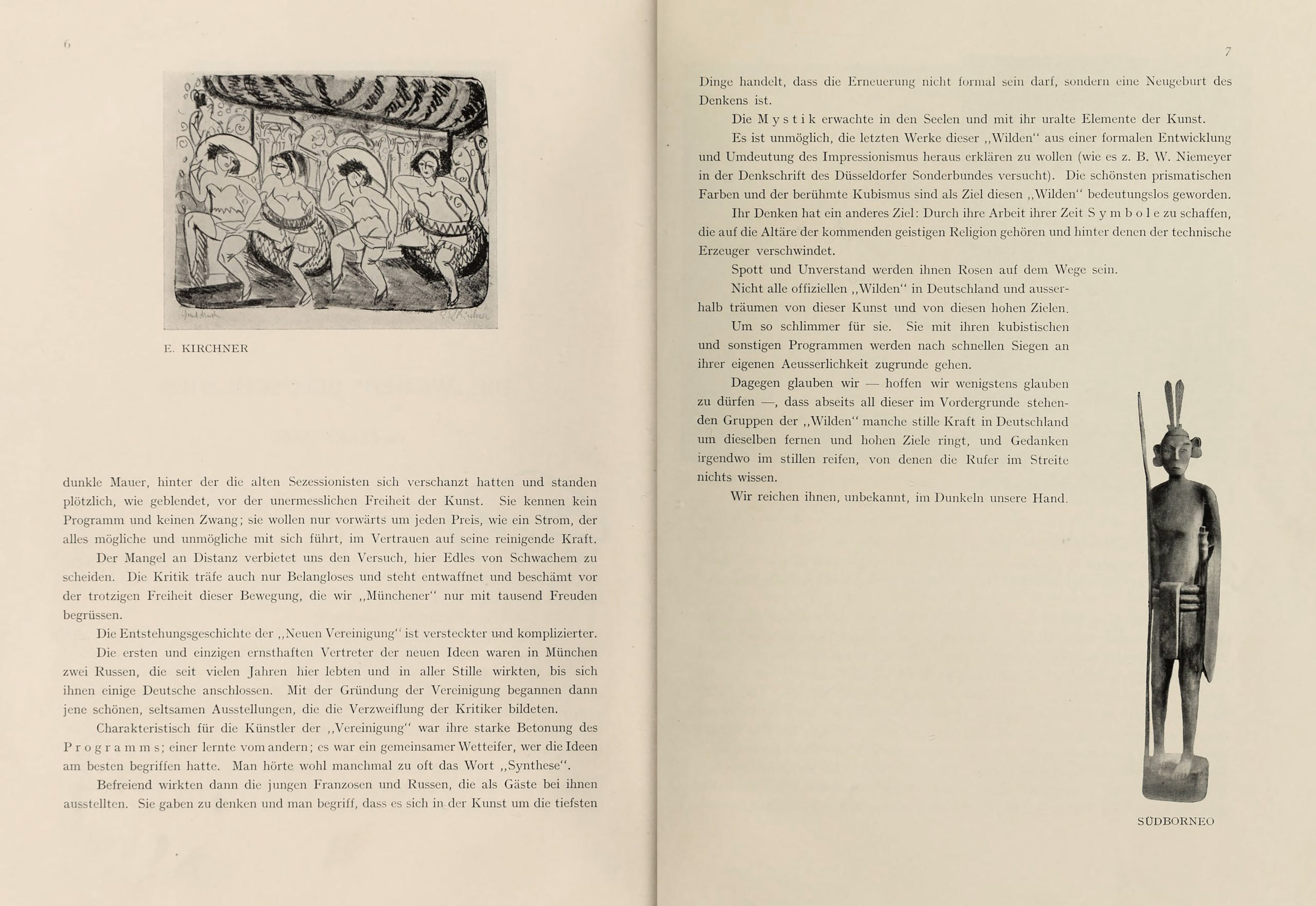

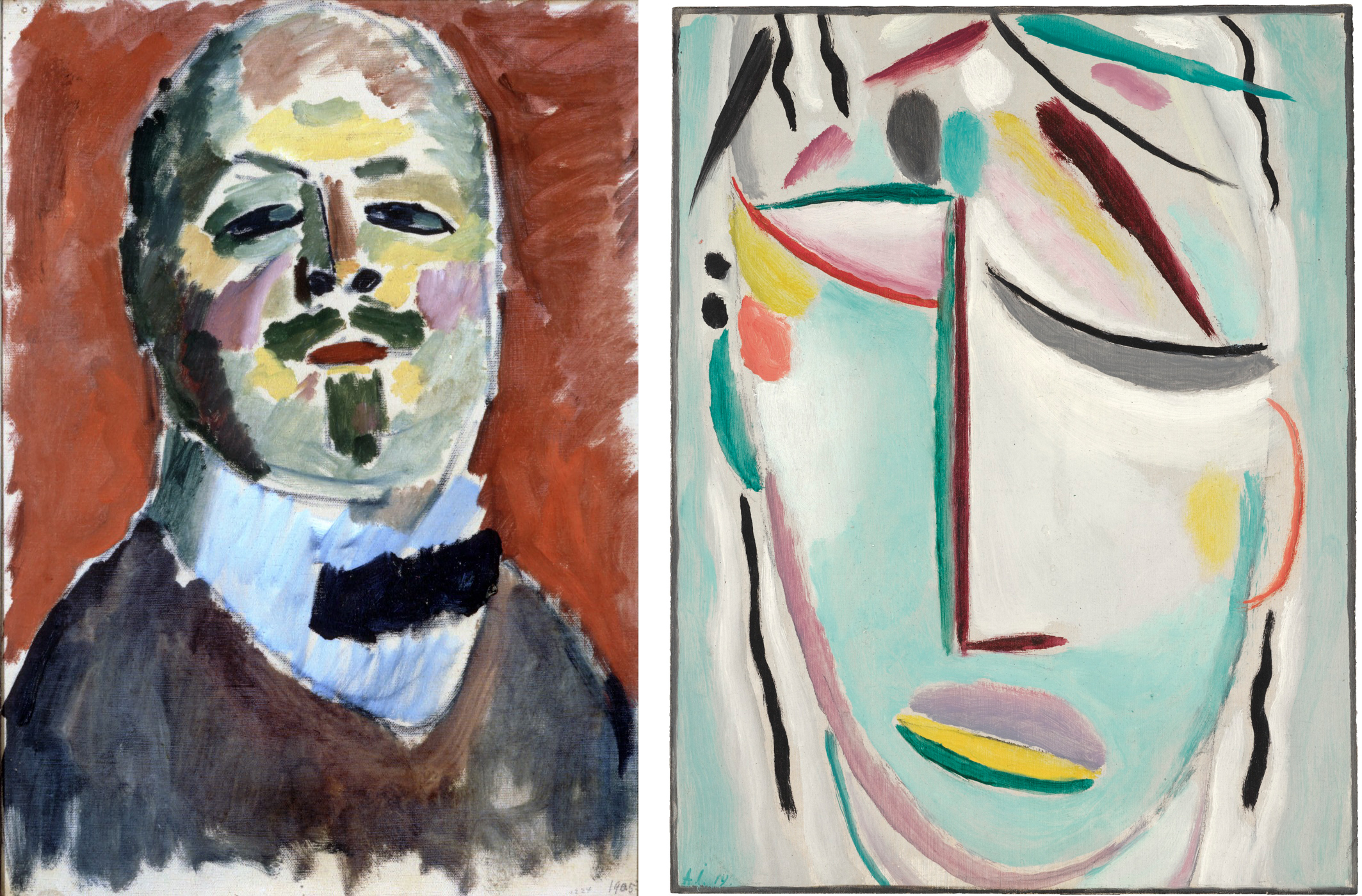

Blaue Reiter pages with Bavarian glass painting and Pablo Picasso’s Woman with Guitar by the Piano, pp. 4-5

In addition to work by its members, the Almanac and the group’s exhibitions featured works by Medieval, non-European, and untrained folk artists — all of which would have been identified at the time as “primitive.’” For example, the illustrations accompanying the first essay, “Spiritual Possessions” by Franz Marc, include a 15th-century German woodcut, a Chinese painting of cats, two drawings by children, and a German folk art glass painting alongside a recent Cubist painting by Pablo Picasso.

As Kandinsky suggested, what all of these disparate works have in common is their rejection or lack of knowledge of the post-Renaissance Western tradition, with its emphasis on artistic naturalism, scientific knowledge, and technological progress. Starting in the 1700s, a growing number of artists and thinkers saw modern science, technology, and urban life as a threat to humankind’s true spiritual vocation. The simple, even crude works of so-called “primitive” artists were seen as exemplars of an approach to both art and life that emphasized higher spiritual aims.

“I did not need nature to prompt me”

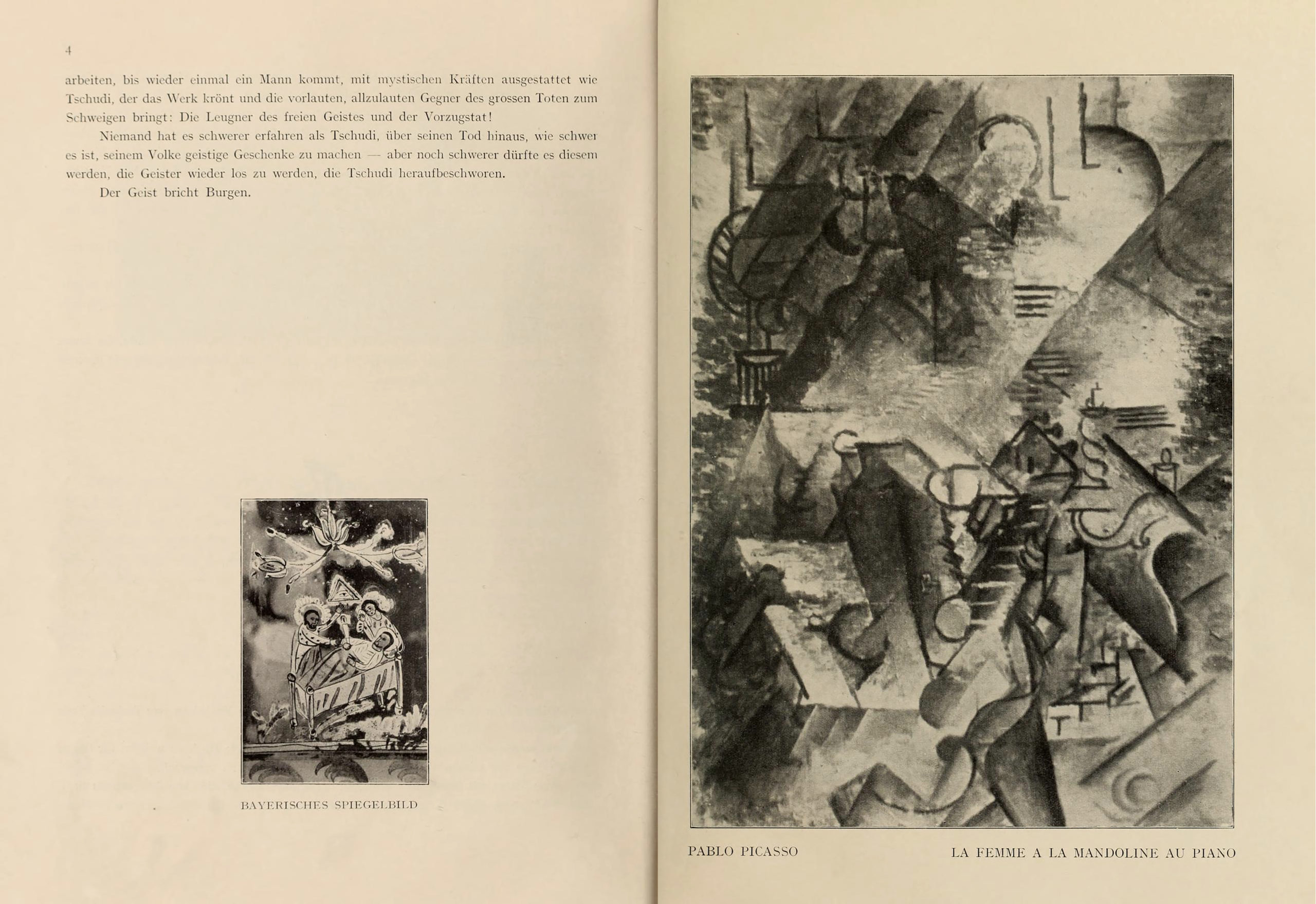

Left: Alexei von Jawlensky, Self-Portrait, 1905, oil on cardboard, 52 x 38 cm, private collection; right: Alexei von Jawlensky, Savior’s Face: Martyr, 1919, oil on linen-finish paper on board, 32.5 x 25.4 cm, private collection

Although he studied painting with the Russian Realist Ilya Repin, Alexei von Jawlensky deliberately rejected his training in favor of a childlike simplicity and directness in his later works. For example, his 1905 Self-Portrait, while painterly and simplified, is a convincing likeness of the artist, with naturalistic proportions and chiaroscuro modeling. The coloring is bright, but based on close observation — warmer red tones appear on the cheeks, nose, and forehead, and cooler tones define the eyes, temples, and jawline.

The later work, Savior’s Face, was part of a series of portraits called “mystical” or “abstract heads,” which the artist noted were not executed from nature:

I sat in my studio and painted, and I did not need Nature to prompt me. It was enough for me to immerse myself in myself, to pray and prepare my soul to attain a religious state.Cited in Jürgen Schultze, Alexej Jawlensky (Cologne, 1970), p. 39.

Here, the childlike simplicity of the work serves as a guarantor of the artist drawing, with naive directness, from an inner, mystical vision he has of the savior’s face, rather than depicting external appearances.

Folk art

Many of the Blaue Reiter artists were particularly interested in folk artists who had no professional training in art. Kandinsky and Gabriele Münter encountered a common Eastern European type of folk art, Bavarian glass painting, when they left Munich for the small town of Murnau.

Gabriele Münter, Still Life with St George, 1911, oil on cardboard, 51.1 x 68 cm (Lenbachhaus, Munich)

Münter’s Still-Life with St George is a composition of folk-art objects that she had collected. A theme of nature emerges in the flowers, chicken, and figurines of what appear to be walking peasants, while spiritual notes are sounded by the two statuettes of the Virgin Mary holding the Christ child, as well as Saint George in the upper left.

The style of the work reinforces these themes. Münter’s blunt, heavy brushwork and crude drawing style matches the rough-hewn simplicity of the folk art objects she admired, while the highly saturated colors in the flowers, Saint George, and the rightmost Virgin Mary glow almost supernaturally against the dark, earthy tones of the rest of the work.

Music

The group’s belief that art had to go beyond merely representing material reality also took inspiration from music. Several of the essays in the Almanac were about music, including one by experimental composer Arnold Schönberg, and the sheet music for three compositions was included at the end of the Almanac.

Vasily Kandinsky, Improvisation 28 (second version), 1912, oil on canvas 111.4 x 162.1 cm (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York)

Kandinsky in particular admired the way that music stirred inner emotional and spiritual states through abstract means, by combinations and sequences of sound, without attempting to imitate nature. Seeking a visual equivalent, Kandinsky theorized that painters could do the same by creating compositions of pure color and form. Although it would take several years before he was confident enough to produce pure-abstract works on this principle, Kandinsky gave his works musical titles such as “composition” and “improvisation” in order to encourage viewers to ignore their apparent subject matter and concentrate on their color harmonies.

The Blaue Reiter group was highly eclectic both in its influences and its output, but the core of the movement was based around the desire for a new Renaissance in art, one dedicated to expressing inner emotional and spiritual states, rather than simply reproducing the outer appearances of material objects. “Primitive” folk art and abstract musical compositions provided key models for their quest.

Notes:

- Translated in Kenneth C. Lindsay and Peter Vergo, eds., Kandinsky: Complete Writings on Art (New York: Da Capo Press, 1994), p. 113.

- Ibid.

Additional resources:

Read more about reverse-glass painting and Der Blaue Reiter artists