Peter Behrens, Turbine Factory, 1909-10

The establishment and evolution of AEG—the initials for the German Allgemeine Elektricitäts-Gesellschaft, or General Electric Company—was quintessentially linked to the rise of modernism. Founded in Berlin in 1883, AEG pioneered modern, large-scale industrial development. In 1887, having purchased several patents from Thomas Edison, the firm began producing electric light bulbs. Just over a decade later, AEG was not only one of the fastest growing companies in Germany, but a world-leader in the production of generators, cables, transformers, motors, light bulbs, and arc lamps.

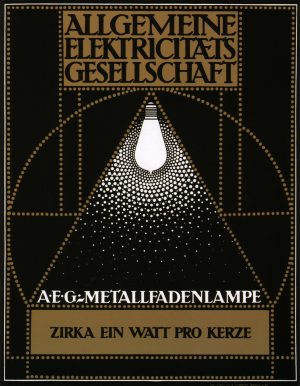

Peter Behrens, Poster for Allgemeine Elektricitäts Gesellschaft (AEG), 1910

Behrens and AEG

How exactly Peter Behrens—a painter turned graphic designer—came to receive his first commissions from AEG in 1907 remains somewhat unclear. But the credentials Behrens’ brought to this appointment were substantial, and his success within the industrial powerhouse was immediate. Prior to his tenure at AEG, Behrens had acted as artist-in-residence at the Darmstadt Artist’s Colony, headed the Kunstgewerbeschule (“School of arts and crafts”) in Düsseldorf, and with Hermann Muthesius, Josef Hoffmann, and Joseph Maria Olbrich, among others, was a founding member of the Deutscher Werkbund (German Association of Craftsmen).

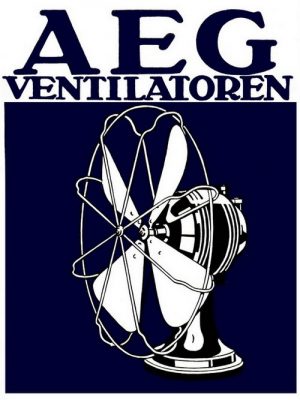

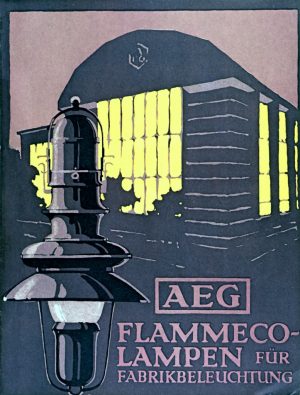

Behrens’ first assignment for AEG involved the re-design of arc lamps—utilitarian hanging lamps intended for factories, warehouses, railway stations, and other public buildings. In his work in Darmstadt and Düsseldorf, Behrens had advocated for a functionally-guided approach to industrial design. “Design,” he wrote, “is not about decorating functional forms—it is about creating forms that accord with the character of the object and that show new technologies to advantage.” Thus while there was little about the existing AEG lamps that could be functionally improved, Behrens succeeded in formally enhancing them. He made the lamp’s joints as few as possible, streamlined their moldings and contours, and adjusted their overall sculptural properties and proportions according to artistic principles. The new lamps were so successful that AEG promptly invited him to design the AEG trademark, as well as its kettles, coffee pots, fans, clocks, a dentist’s drill, and even factory buildings.

Peter Behrens, Poster for Allgemeine Elektricitäts Gesellschaft (AEG), 1912

The impact of design

Today, the idea of an artist designing commercial, mass-produced objects or housewares is unremarkable. Numerous celebrity designers have product lines with major retailers like Target and Walmart, and as consumers, we are conditioned to look for names and labels. We associate labels with a standard of design and quality, and our fundamental reliance on “name brands” simplifies daily shopping. But this was not yet the case at the turn of the twentieth-century. The European industrial revolution had led to the rise of the factory and systematized mass-production, and at the same time had contributed to the demise of the artisan and individualized production. Retailers no longer sold what they themselves had produced. Rather, they sold the anonymous, white-label products that had been manufactured in factories and hawked by wholesalers. Thus when shopping for a kettle, for example, the consumer could find the same, standardized product in a dozen of different stores. But he had no choice in terms of the kettle’s design, material or make. Moreover, because there were no labels or name brands, it was nearly impossible for him to distinguish a good-quality kettle from an inferior model.

Peter Behrens, Poster for Allgemeine Elektricitäts Gesellschaft (AEG), c. 1910

AEG was one of the first major manufacturers to develop a label as a means to distinguish their products from those of their competitors. Beyond this, AEG was the first firm to invest in the art of industrial design. It wanted to sell not only the best-functioning kettles, but also the most streamlined, aesthetically pleasing kettles. AEG changed the nature of mass-production not only in its decision to hire talented artists like Behrens, but also its immense size and ever-increasing economic power.

AEG’s introduction of design to industrial production heralded a new age of capitalism. It also created a new role for the artist within the industrial marketplace. According to Behrens, the role of the artist was to give form to the culture in which he lived. In the age of industry and modernization, therefore, the artist was not to replicate historical models and age-old forms, but was to create designs that expressed the spirit and rhythm of the moment. Still, good design was never to sacrifice aesthetics in favor of functionality. This was also the case in architecture. In designing highly functional factory buildings for AEG in Berlin, Peter Behrens chose not to emphasize pure functionalism. Rather, he sought to contextualize his modern constructions within the ever-evolving political and social milieu of early-twentieth-century Europe.

AEG Turbine Factory

Located in the Moabit district of Berlin, the AEG Turbine Factory was Behrens’ first factory design. The structure was to house the production of steam turbines—engines that use pressurized steam to generate electricity—a rapidly growing industry in the early-20th century Germany, as the country’s maritime power developed in rivalry with that of Britain. The essential contours of the factory—a steel-frame rectangular structure, approximately 122 meters long, 40 meters wide and 26 meters tall—were specified by AEG’s turbine fabrication director Oscar Lasche. The main assembly hall had to accommodate two large cranes, capable of lifting 100 tons and installed at such a height that the largest turbine parts could be lifted over the machines on the assembly floor. Smaller, flanking constructions were also necessary for storage and secondary manufacturing operations, and it was imperative that railroad cars enter directly into the work space.

AEG Turbine Factory interior, 1909

As a self-taught architect, untrained in engineering, Behrens was willingly reliant on the expertise of Lasche and other talented engineers when it came to the building’s materials and structural dimensions. But as an artist, Behrens was able to give form and meaning to the factory in way that eluded the engineers. Behrens saw the Turbine Factory as a symbol of modernism, and its attributes of speed, noise and power. He wanted to make the interior and exterior as simple as possible, and in collaboration with the engineers chose to use fewer, but more massive girder frames than was commonly employed in such a large building. The AEG Turbine Factory was to be a temple dedicated to a new age of production. The classicism evoked in its reinforced concrete, pedimented façade was not of bygone traditions, but a new classicism that expressed the industrial advances that were reshaping contemporary life.

AEG-Turbinenhalle, Berlin-Moabit, Juli 2013 (photo: Bernd, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The monumental iconic façade—at the center of which stood Behren’s hexagonal logo for the AEG—was also to become the company’s corporate face. It is here that we can best recognize how Behrens used symbolically-charged forms to create new functions. In its materiality, the concrete façade serves no structural purpose. But in its mass, it accomplishes what the elongated steel beams of the structure’s skeleton does not. The Turbine factory was not Germany’s first major iron and glass building, nor was it the country’s first industrial construction. It was unprecedented because it served as a cultural icon of modern industrial power. It expanded the realm of the architect’s work and established new guidelines for mass-production.