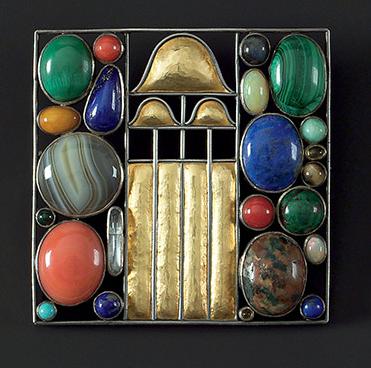

Josef Hoffmann, Brooch, 1907, silver, partly gilt, agate, coral, lapis lazuli, malachite, turquoise and other semi- precious stones (private collection)

One glance at the brooch designed by Josef Hoffmann and we get an immediate sense of the person who wore it: sophisticated, uncompromising, worldly, and wealthy, with a deep commitment to a new and modern idea of beauty. Held in a rigid scaffolding of thin metal lines, the brooch holds its luxury in perfect check. The visual pleasure of the object comes not only from the richness of its varied materials—coral, lapis, gold, agate—but from the exquisite asymmetry of the left and right sides. Nature and culture are held in perfect balance here, the dazzling organic beauty of the stones countered by the geometric order and the austerity of the metal outlines, the solidity and weight of the gems playing against the open space of the brooch. One can imagine the woman who wore it living in a world in which her most prized possession would be a gilt cigarette holder.

The brooch perfectly embodies the aesthetic of the Vereinigung für Kunsthandwerk (Arts and Crafts Association) Wiener Werkstätte (Viennese Workshops, abbreviated WW). Like many other design movements of the first decades of the 20th century, it aimed to improve real life, but only for the small elite circle that floated from salon to opera to cafe along the Ringstrasse, the main boulevard of Imperial Vienna. Despite its Imperial splendor, the city was roiled by antisemitism, conflicts between the various ethnic and language groups within the Empire, class conflict, and new ideas about gender and sexuality that bumped up against a deeply conservative culture.

Founding and aims

The Wiener Werkstätte (WW) grew out of the Vienna Secession, an organization formed in 1897 to offer artists greater aesthetic freedom and connection to wider European currents. Embracing the motto of “To Each Age its Art, to Art its Freedom,” Secession artists turned their back on the historical styles then dominant (Gothic, or classical, for example), and instead aimed to embrace the modern world. Rather than invoking well known figures from mythology or Christianity, the artists of the Secession wanted to express new ideas on love, nature, human existence, etc. and to do so using a new language based on non-Western and folk sources, as well as direct inspiration from nature. The same was true for the Wiener Werkstätte.

In 1903, architect Josef Hoffmann and graphic designer Kolomon Moser (both Secession members), formed the WW and remained committed to the Secession’s freedom, and openness to the new—but for utilitarian objects. Their endeavor was financially supported by the wealthy textile manufacturer Fritz Waerndorfer. The project was deeply ambitious, incorporating work in varied media including leather, paper, ceramics, graphic design, furniture, woodwork, and jewelry. In 1910, the WW expanded into fashion and textile design, with showrooms across Europe and in New York.

Located just outside the historic center of Vienna, the workshops would expand to 100 workers. Female designers such as ceramicist Valerie (“Vally”) Wieselthier and fashion designer Maria Likarz played a prominent role. In contrast to many early 20th-century European movements that would aim for mass production, such as the Bauhaus, the WW emphasized handicraft over mass production, a focus evident in the very name of Wiener Werkstätte. In the program for the WW, Hoffmann wrote:

That immeasurable damage caused on the one hand by inferior methods of mass production, on the other, by the mindless imitation of bygone styles, has become a mighty torrent of world-wide proportions. We have lost contact with the culture of our forefathers and are tossed hither and thither by a thousand different desires and considerations. For the most part, handiwork has been ousted by the machine. . . . [1]

Despite the great freedom of the designers, the objects produced by the WW were strongly united by a shared aesthetic. Like Josef Maria Obrich’s Secession building or Gustav Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze, the WW excelled in a kind of linear surface design (called flaschenkunst). Its designers exhibited a taste for luxury materials, repeated patterns, and an underlying geometrical scaffolding. As in the brooch, this resulted in a sophisticated beauty that derived less from extraneous ornament and instead from the beauty of materials, and the slightly elongated and asymmetrical proportions.

Josef Hoffmann, Palais Stoclet (Brussels), c. 1905–11 (photo: PtrQs, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Gesamtkunstwerk and life as art

While many artists and architects in the early 20th century were drawn to the notion of the total aesthetic environment, or Gesamtkunstwerk, perhaps no movement embodied it more than the WW. The concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk was originally derived from the operas of Richard Wagner. The composer saw theater productions as places where all of the arts would work in unison to create an overwhelming sensory and emotional experience, embodied in productions like Wagner’s opera cycle of The Ring.

Dining room of the Palais Stoclet, Brussels, c. 1905–11, designed by Josef Hoffmann. Wall frieze by Gustav Klimt includes enamel, mother-of-pearl and gold leaf.

For visual artists interpreting the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk, every last detail of the lived environment would become part of a coordinated ensemble, turning life itself into a giant work of art. The entire aesthetic could as well be read from a brooch as from a building. The most complete embodiment of the Gesamtkunstwerk was Hoffmann’s Palais Stoclet, built in Brussels for Adolphe Stoclet. Given an unlimited budget, Hoffmann, Klimt, and assorted WW craftsmen turned the entire house into a coordinated environment, from the two dimensional exterior, lacking historical references, to the gleaming knobs on the bathtubs. Every element partook of a refined luxury, with polished stone, wood, metal, and gems fitted into severe geometric compositions.

In its rejection of the shoddy machine-made environment and the desire to transform life into an aesthetic program, the WW drew on the earlier British Arts and Crafts movement. But if its upholding of craft workshops relates back to the Arts and Crafts ethos, the WW could not be more different. In Britain, the artist William Morris had celebrated a do-it-yourself spirit, simplicity in workmanship, and a genuine inspiration from nature. In contrast, in the objects turned out by the WW, nature is fitted into a pre-existing schema, glamorous and refined rather than rustic. Materials are polished and cut to the finest degree. Kolomon Moser’s Highback Chair differs from William Morris’s armchair in its willful lack of concern for comfort, embodying the philosophy that it is “better to look good than to feel good.” One can hardly sink into the stiff lines and taut back of Moser’s chair. The self-conscious sitter utilizing such a chair would seem concerned, first and foremost, with being seen in it, rather than being comfortable. Like the brooch, the chair displays a repetition of geometric elements, in a contained field. Its luxury comes from its slightly exaggerated proportions and austere design.

Josef Hoffmann, Flatware, 1905, manufactured by the Wiener Werkstätte, Vienna (The Museum of Modern Art)

The same can be said for the silverware designed by Hoffmann for the WW. In contrast to the sleek and understated cutlery, earlier formal silver tableware, like this eighteenth-century tureen, looks fussy, overdone, and decadent. The animals, crests, and large foliage ornamentation seems to obscure the shape and surface of the vessel rather than to enhance it and are redolent of a world of aristocracy and staid manners.

Edme-Pierre Balzac, Tureen with Cover, 1757–59, silver, 26 × 23.2 × 39.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In contrast, Hoffmann’s table service is stripped of any surface embellishments. Lacking the extraneous curves and floral designs of the tureen, the proportions of the flatware echo those of the chair, and the brooch–elongated, elegant and asymmetrical. The implements are designed to impress rather than for ease of use or serving. This set seems to be less about satisfying appetite and far more about looking good while eating. If the straight lines make it hard to get that soup on the spoon, so be it. Such silverware was designed to be wielded in a dining room conceived as a work of art, playing against the elongated shapes of furniture, the rhythms of the wallpaper, the patterns of the rug, the light fixtures, and the after-dinner schnapps set.

One imagines walking into a dinner party in such a WW dining room, dressed appropriately, of course, in WW clothing, where the shapes of the garment and its texture and pattern upstage the body completely. The loose-fitting Wiener Werkstätte dress (above) was entirely modern in its overthrow of corsets and the hourglass silhouette of 19th-century fashion. Like the brooch, the Secession building, and the other WW objects, the dress restricts its decoration to limited fields, which work against the dark fabric and proportions, giving it an understated elegance.

Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein, 1905, 70.7 x 35.6 in. (Neue Pinakothek, Munich)

So, too, these Wiener Werkstätte designs are like the portraits painted by Gustav Klimt, balancing decadent touches of ornament against geometric severity. It is surely no coincidence that this aesthetic emerged in Imperial Vienna, a city that remained buttoned up and proper despite the chaos of the time and its parliamentary crises, social unrest, religious and ethnic divisions that teemed beneath the surface.

World War I: a finale

While the style of the WW perfectly expressed the taste of its wealthy and highly cultured patrons, the Austro-Hungarian empire in which it flourished would not last much longer, the end of World War I bringing it to a finale. Already by 1914, the WW had run into severe economic woes and was reliant on its new patron/benefactor Otto Primavesi and a series of financial restructurings. A banker by trade, Primavesi and his wife, Eugenia, were among the most important patrons of both Josef Hoffmann and painter Gustav Klimt.

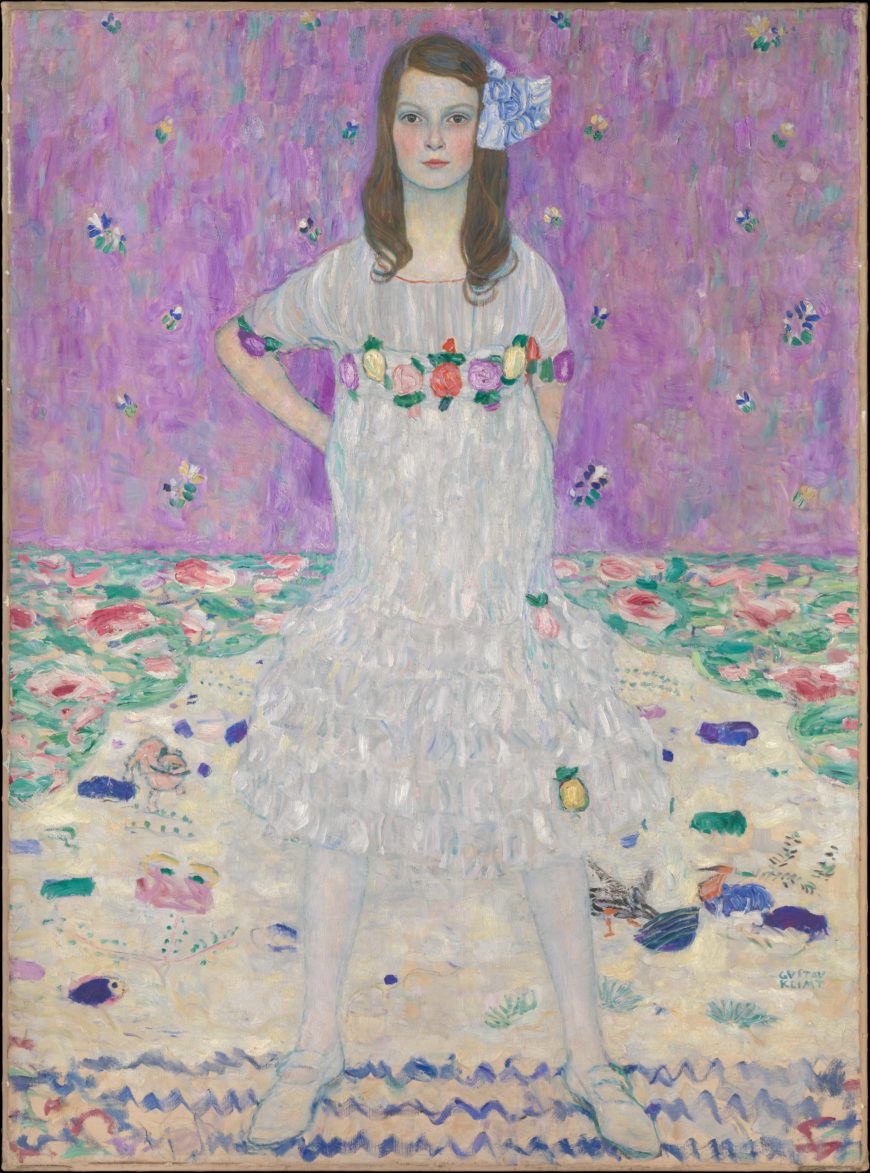

Mäda Primavesi (daughter of Otto and Eugenia Primavesi),oil on canvas, 1912–13, oil on canvas, 149.9 x 110.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Aesthetically liberating and beautiful, the WW was only for those who had the wealth, freedom, and education to fully appreciate it. Given its inward-facing focus on a small circle of cultured patrons, and on the ultimate refinement of taste, the Wiener Werkstätte floundered financially during the First Austrian Republic, a time period framed by the two world wars. Such focus on rarified aesthetics was hard to sustain in a period of material shortages and worker agitation.The deep depression that spread over Europe in the early 1930s led to the Wiener Werkstätte’s demise; the objects produced in its workshops remind us of a world, too, that has all but disappeared. Yet the near-exact reproductions of Hoffmann’s brooch that sell today for $8,000 in the gift shop of New York City’s Neue Galerie reveal the continuing hold that the Wiener Werkstätte has on our contemporary taste and our collective fantasies.

Additional resources

“Vienna 1900: Design/Art and Crafts 1890–1938,” Museum of Applied Arts (MAK)

Wiener Werkstätte Archive (MAK)