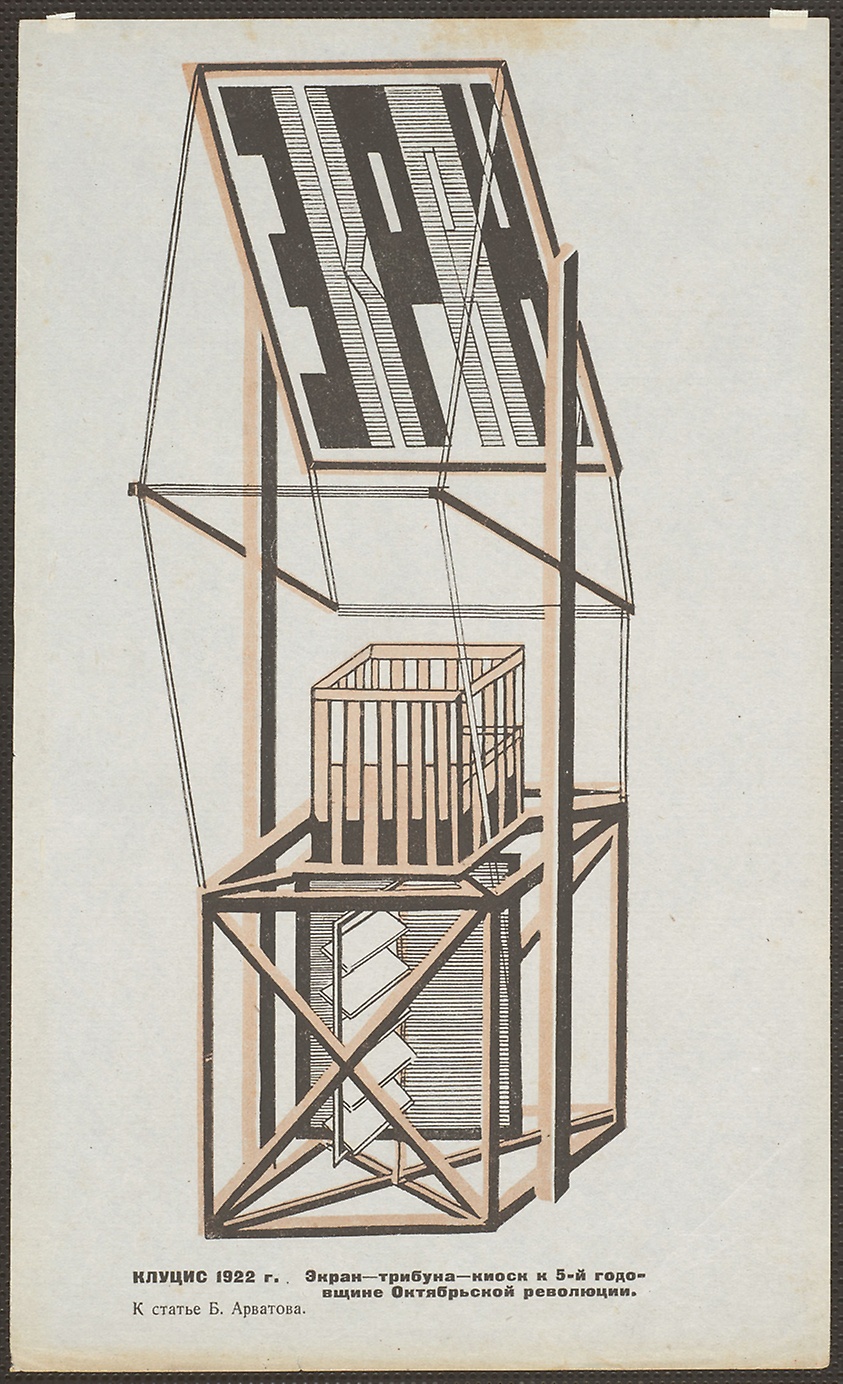

Gustav Klutsis, Screen-Platform-Kiosk for the Fifth Anniversary of the Great October Revolution, 1922, color lithograph on paper, 259 x 157 mm (Art Institute of Chicago)

Gustav Klutsis’ kiosk is a utilitarian Constructivist design from the early 1920s. The structure is economical and based on a systematic rational design stripped down to its essential supporting elements. It is a simple multi-purpose structure containing a bookshelf, a screen for projecting newsreels, a platform for a speaker, and a board for posters. In this single object we see the fundamental aim of the Constructivists: the creation of utilitarian works whose structural organization and materials were aligned with the ideology of communism and contributed to the creation of a new society.

The kiosk was intended to be a public locus for spreading “agitation and propaganda,” often shortened to agitprop. The Agitation and Propaganda Section was a crucial arm of the Central Committee of the Communist Party. Its work included conveying information about communism and the Soviet government’s policies and goals, as well as more directly practical information intended to support the development of the people.

Agitprop played an important role in the creation of the new Soviet society, helping to turn a poor agricultural country of largely-uneducated peasants into a modern nation of literate industrial workers. Propaganda directed people to become dedicated Communist Party members and contributors to the new socialist society. As artists and designers, the Constructivists were closely involved with Soviet agitprop during the 1920s.

A New Environment

After 1921 the Constructivists renounced the creation of mere art objects and entered a “productivist” phase during which they attempted to design utilitarian objects for factory production. Given the nascent state of Soviet industry at the time, this effort was largely unsuccessful, however, and very few Constructivist designs made it past the drawing board.

Alexandr Rodchenko’s Workers’ Club is a rare documented example of Constructivist furniture designs that were actually made. It was exhibited in the Soviet pavilion (itself a famous example of early Russian modernist architecture by Konstantin Melnikov) at the 1925 International Exposition of Decorative Arts in Paris.

Like Klutsis’ kiosk, the furniture of the Workers’ Club is made of basic, undecorated geometric forms that display their structural purpose and integrity. The material — wood — is economical, and some of the furniture (the bookshelf, podium, display board, projection screen, and bench) was collapsible so it could be stored when not in use. The color scheme was red, gray, white, and black, which created a distinctive graphic quality as well as highlighting red, the signature color of the Communist Revolution.

Also like Klutsis’ kiosk, the purpose of the Workers’ Club was to foster the new communist society. It was both a center for education and a place for the new workers to meet socially. As such, it is the best example ever made of the Constructivist ideal of designing an environment to foster the new communist life. It was, however, not mass-produced, nor did it serve as a prototype for factory production. It was in the end closer to an artisan-produced conceptual art project than it was to a modern industrial product.

Designing for life

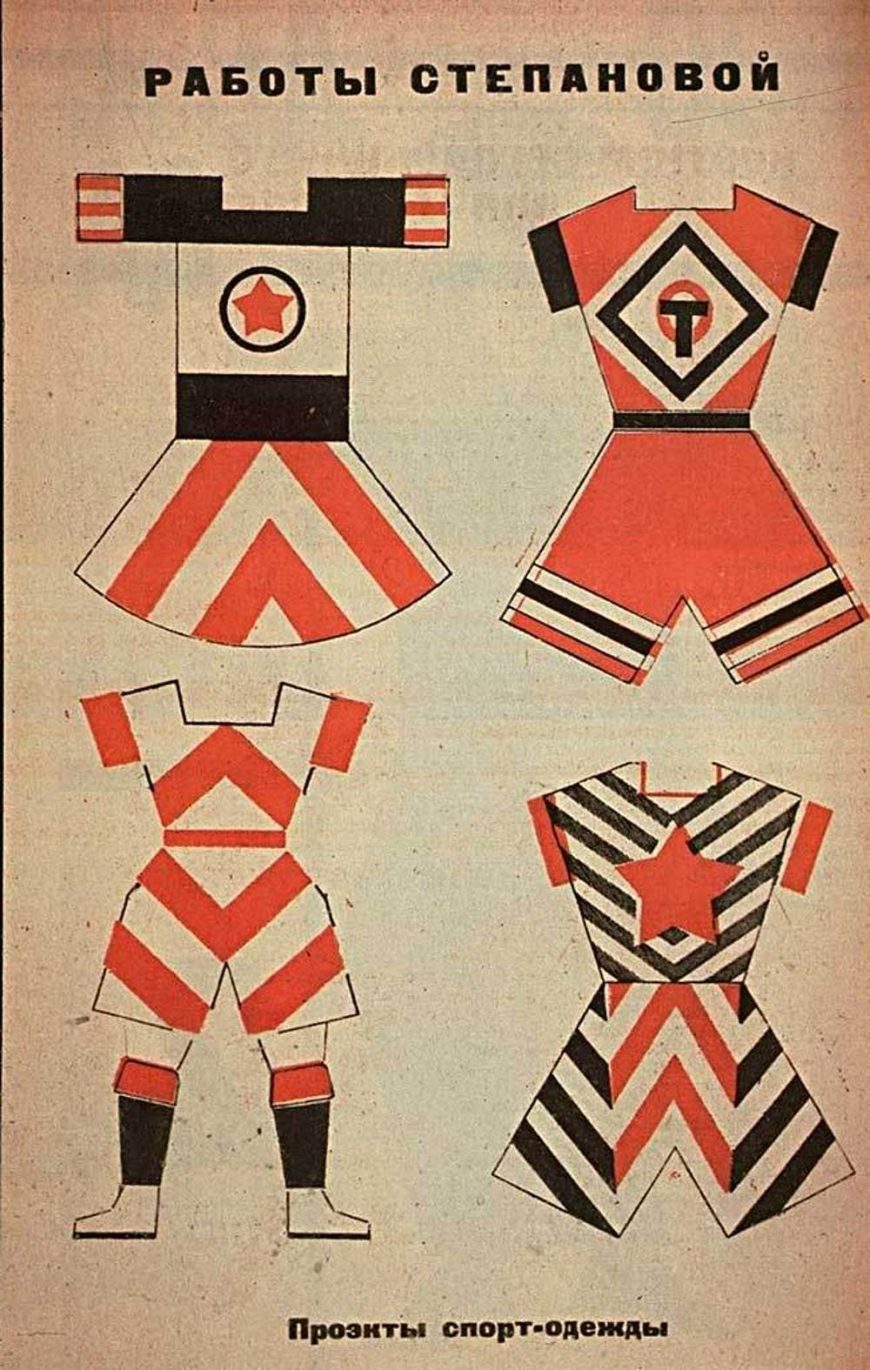

The everyday utilitarian objects designed by the Constructivists included clothing. Vavara Stepanova published her ideas about clothing designed for pure functionality, accompanied by illustrations of her sports clothing designs. They used a minimum of cloth cut into boxy shapes that would be easy to manufacture and comfortable to wear. The graphic textile designs were intended to distinguish the individual athletes or teams for spectators viewing from a distance.

Stepanova’s designs rejected the pitfalls of bourgeois “fashion,” in which designs change rapidly to promote consumerism and signal gender and class differences. By subsuming all stylistic decisions to the unifying Constructivist visual language of basic geometric forms, strong diagonals, and a restricted palette of red, black, and white, clothing design itself could reflect the communist ideals of rigorous functionalism and class leveling.

Working in Industry

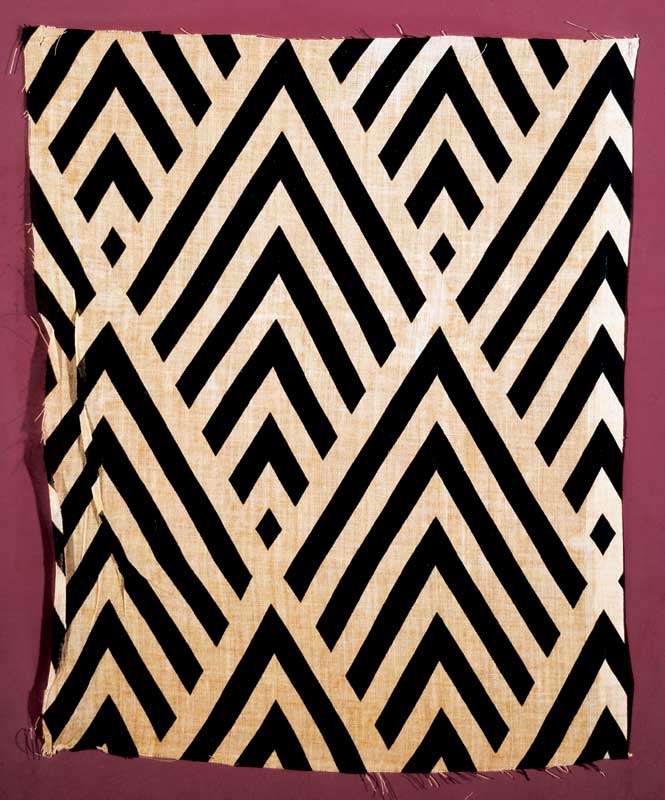

Stepanova and Liubov Popova were the only prominent Constructivists working as designers in industrial production during the 1920s. They were employed by the First State Textile Printing Works to design textile patterns. Their designs were aggressively abstract and economical, using repeating patterns of basic geometric forms in black and white and sometimes one or two colors. They described their designs as a form of Constructivist propaganda, but their success in Constructivist terms was limited.

Although their textile patterns were mass-produced and used to make clothing, their employment in the textile industry was exclusively that of conventional artisan/designers. It did not reflect their Constructivist goal to be a new type of artist-producer fully engaged in all areas of the production and marketing processes, from developing chemicals for dyes to designing store window displays and advertisements.

Advertising and Posters

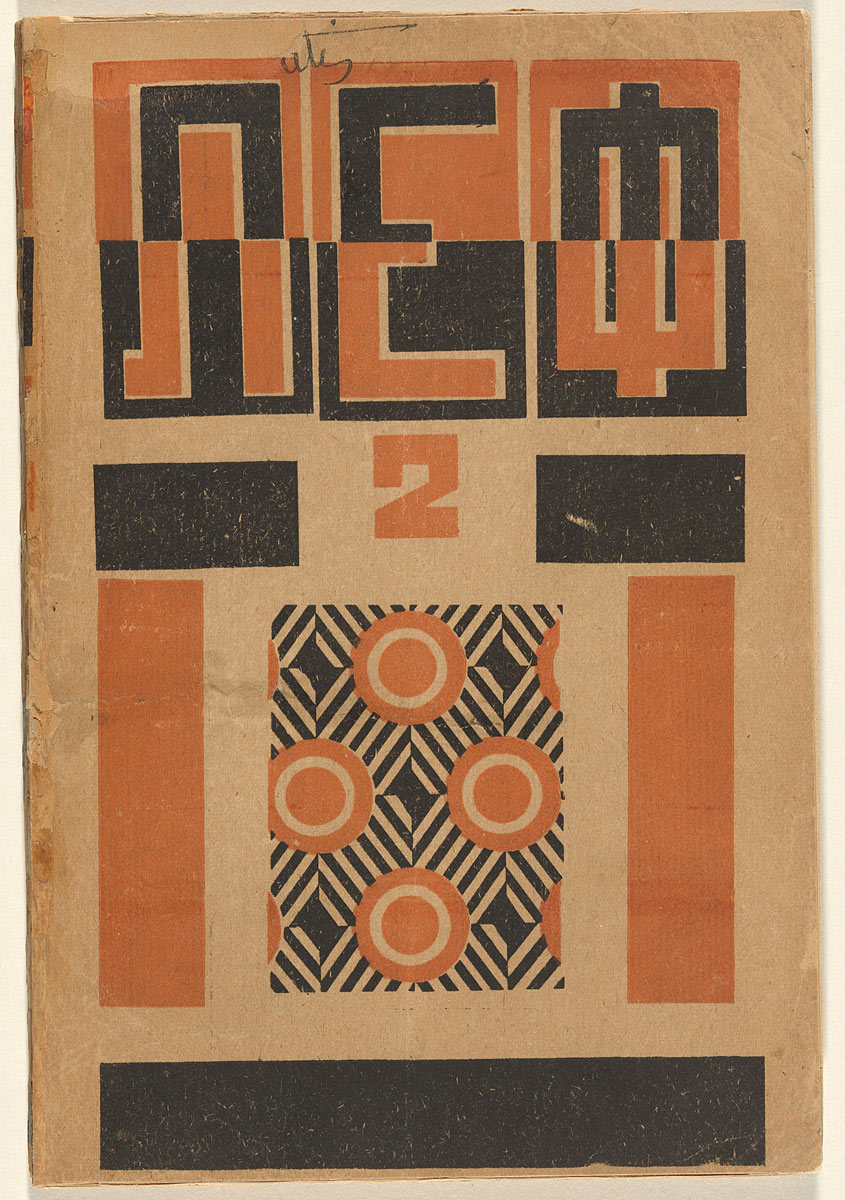

Ultimately, the most widely disseminated Constructivist products were their advertising posters and graphic designs for product packaging, books, and magazines. Rodchenko saw his work in advertising as a direct engagement with building the Soviet economy during the NEP (New Economic Policy) period of the 1920s.

His poster for rubber overshoes combines representation and abstract geometric forms to convey its message. White diagonal lines representing heavy rain are prevented from hitting the globe by an enormous rubber overshoe. The color scheme is simple: red, yellow, blue, black, and white. The simple sans serif font uses different colors to create emphasis and support the visual message. The blue background suggests water, while the USSR in red dominates the globe. Not only will buying rubber overshoes keep your feet dry, it will help to maintain Soviet dominance of the world.

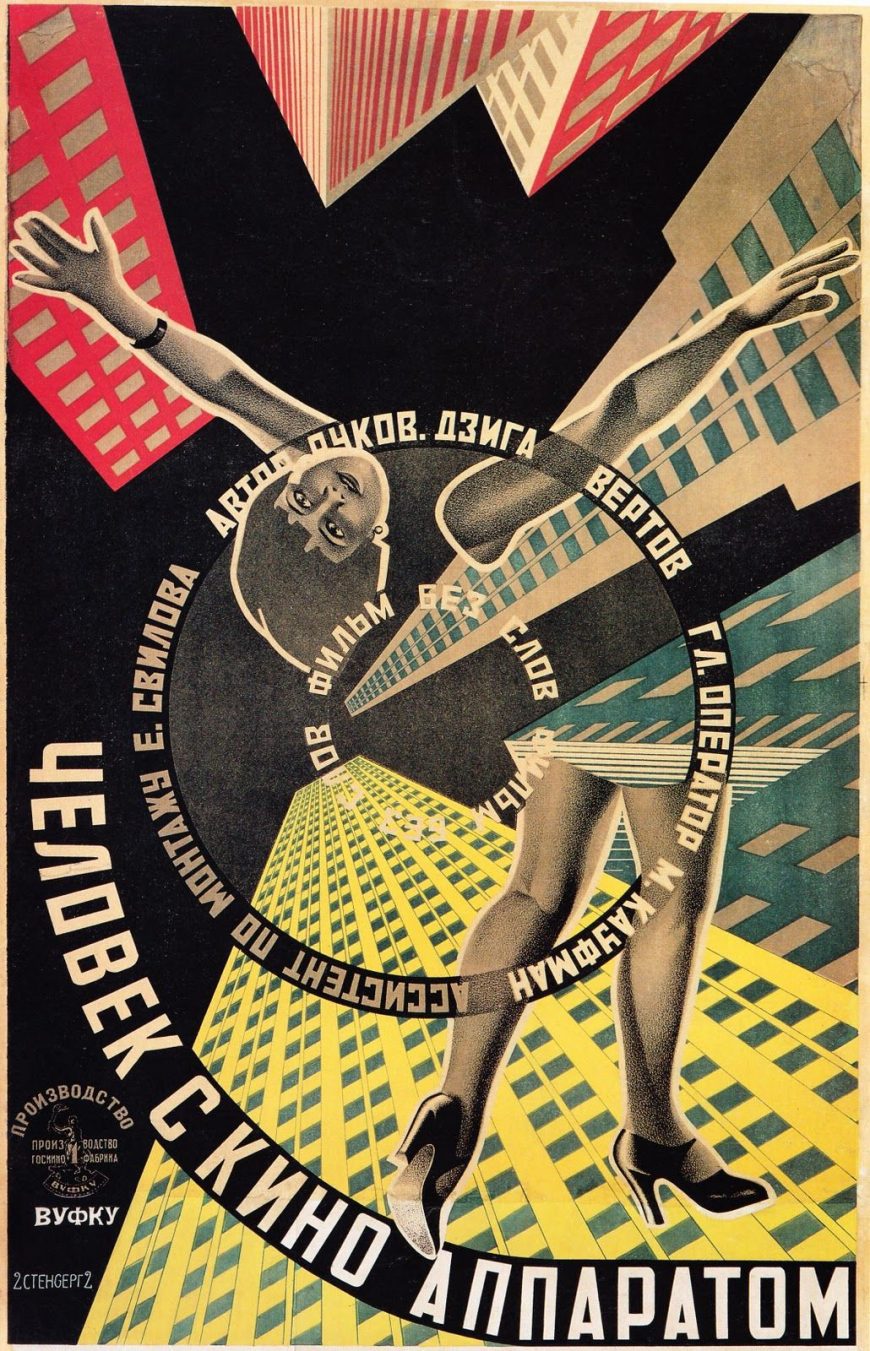

Georgii and Vladimir Stenberg, Poster for Dziga Vertov’s The Man with the Movie Camera, 1929, lithograph, 106.2 x 70.5 cm

The Stenberg Brothers’ poster for Dziga Vertov’s The Man with the Movie Camera uses a low vantage point to depict a dizzying array of skyscrapers rising diagonally into space and suggesting the kind of modern, productive, and prosperous communist city shown in the film. The text is formed into a spiral that also appears to rise toward the center, while a woman’s arms, legs and head are arranged to suggest a dancer spinning through space. The abstract forms of modern design have become the forms of the urban environment and the human body. The emphasis on dynamic compositions and hard-edged geometric design made the Constructivist style a perfect vehicle for fostering excitement about the new Communist/industrial society.

Turning to Photomontage

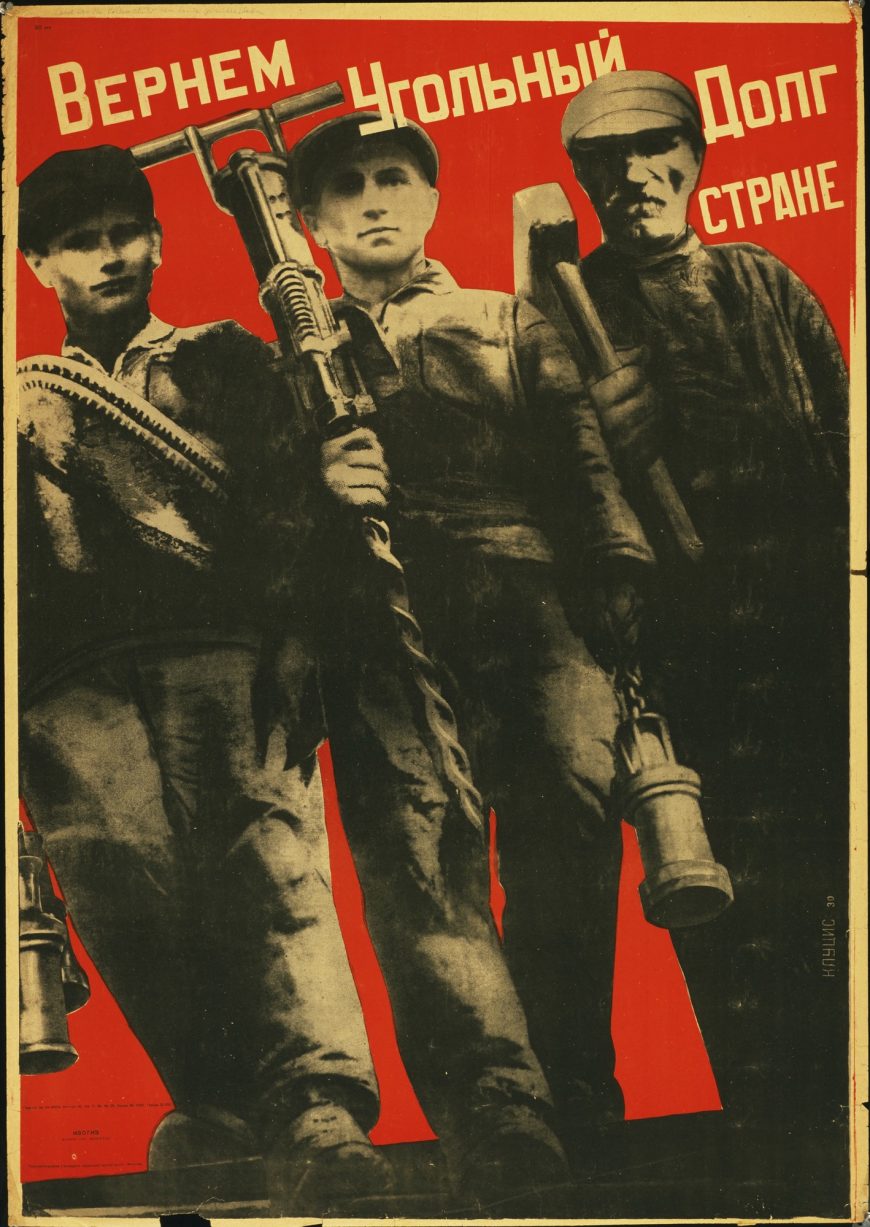

By the late 1920s photography and photomontage had come to dominate Constructivist poster design. This was part of a widespread turn away from modernist abstraction in Soviet culture and an embrace of realistic styles that would be more easily understood by the masses. Klutsis’ We Will Repay the Coal Debt is one of many posters he designed as propaganda for the first Five Year Plan—Stalin’s drive to industrialize the nation.

Although the main content of the poster is a photograph of workers, the overall design and color scheme remains Constructivist. The figures are closely cropped to make them appear large, and they loom up over the viewer at a diagonal. The dynamism of the diagonal is further emphasized by the drill and mallet held by two workers, as well as the belts strapped across the third worker’s chest. The flat red background and sans serif text placed at an opposing diagonal and partly overlapping the central worker turn the photograph of three individuals into a timeless image of the Soviet workers’ determination to support the economic goals of their society.

Additional resources:

Permanent Reconstruction of Rodchenko’s Workers’ Club in Kunstmuseum, Liechtenstein

Read more about Liubov Popova at the Tate Museum

Christina Kiaer, Imagine No Possessions: The Socialist Objects of Russian Constructivism (Cambridge: M.I.T. Press, 2005).

Christina Lodder, “Liubov Popova: From Painting to Textile Design,” Tate Papers no. 14.

Christina Lodder, Russian Constructivism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983).

The Great Utopia: The Russian and Soviet Avant-Garde, 1915–1932 (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1992).