Natalia Goncharova’s Gardening is an example of the contradictions of early-twentieth century Russian modernism. It simultaneously faces outward and inward, forward and backward — outward and forward to engage with some of the most radical trends of European modern art, and inward and backward to reflect on traditional Russian subjects and themes.

Looking forward

In terms of style, Gardening is aggressively modern. With its flat colors and decorative patterning created by the flowers and distant houses, the painting reflects the deliberately simplified style initially developed by the Post-Impressionists in the late nineteenth century. At the same time, the crudely rendered forms of the figures and spatial dislocations suggest contemporaneous painting techniques associated with Fauvism and German Expressionism.

During the first decade of the twentieth century Goncharova and other Russian artists worked hard to assimilate the new styles and attitudes of modern European art. They were able to see many examples of modern art in traveling exhibitions and reproductions in books and magazines. The extensive collections of Ivan Morozov and Sergei Shchukin in Moscow also provided Russian artists with opportunities to view many works by prominent European modernists.

Natalia Goncharova, Peasants Picking Apples, 1911, oil on canvas, 104.5 x 98 cm (Tretyakov State Gallery).

Goncharova was a remarkably prolific and eclectic painter who produced an enormous number of works that show her immersion in contemporary European styles and techniques. Peasants Picking Apples, created a few years after Gardening, depicts a similar subject, but the painting’s forms are flatter and more simplified, now reflecting Goncharova’s assimilation of the formal innovations of early Cubism. This is particularly evident in the simultaneous profile and frontal view of the peasants’ faces and in the hard, angular facets of their bodies.

Peasant life and Russian nationalism

Goncharova’s subjects were at odds with her aggressively international and forward-leaning style. Peasant labor was a popular subject for many Russian modern artists between 1910 and 1913, especially for those associated with Neo-Primitivism, which included Goncharova and her partner Mikhail Larionov, as well as Kasimir Malevich and Aleksandr Shevchenko. Although they were deeply engaged with the developments of European art, Russian modernists were also committed to explicitly Russian themes and subjects — and peasants were a particularly significant subject for them.

Belief in a specifically Russian identity had deep historical roots in Russian culture, which had defined itself since the 18th century in ambivalent relation to Western European culture. Russian modernists maintained this long-standing ambivalence. They embraced many of the ideas and formal innovations of European modernism, but they insisted on interpreting and developing them in distinctively Russian ways.

Peasants who had worked the land for centuries were widely considered to embody the Russian national identity and soul. To assert their difference from Europe, Russian intellectuals described Russian peasants and the land itself as Eastern and Asian or Oriental. Russian peasants were often portrayed as true primitives, uncorrupted by European civilization. Ironically, by embracing the primitive Russian peasant, Russian modern artists were following European precedents, most famously that of Paul Gauguin, who admired and painted the primitive lifestyle of the French peasants in Brittany before he moved to the Pacific Islands.

Embracing Russian folk traditions

Russian Neo-Primitivist artists did not just depict Russian peasants, they also often modeled their styles on traditional Russian folk art, particularly popular woodcuts called luboks, as well as shop signs, embroidery, hand-made toys, and religious icons. Paintings by Mikhail Larionov display varied styles associated with traditional folk art.

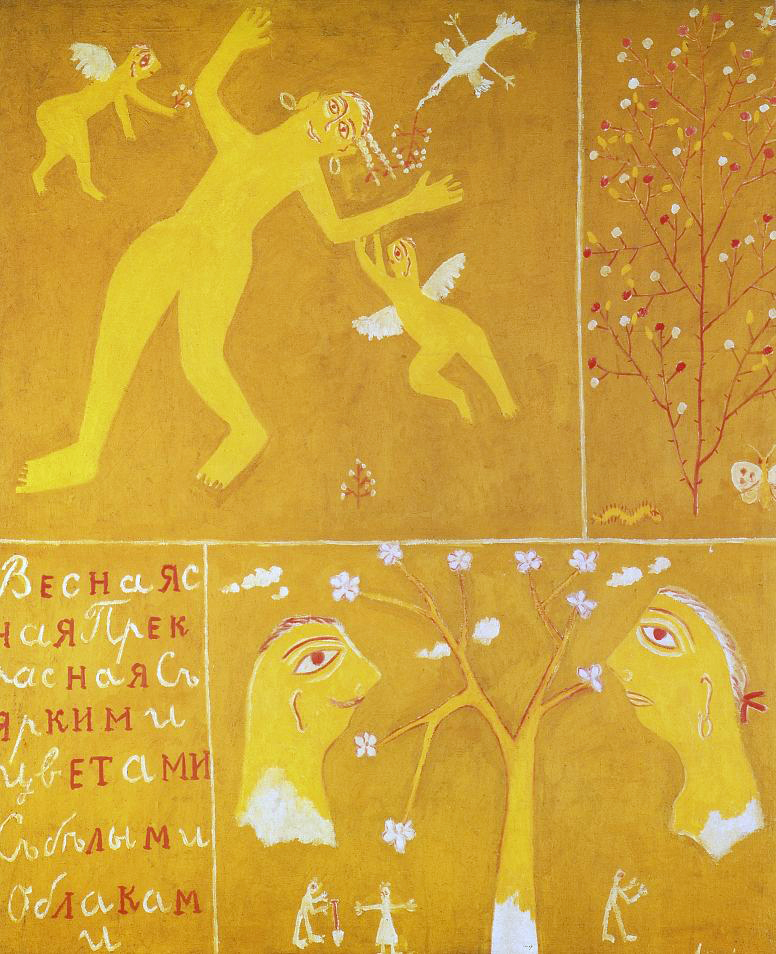

In Spring, instead of depicting peasants performing seasonal labor, Larionov adopted folk art forms to create whimsical panels in bright yellow, red, gold, and white that represent the season of fertility and new growth through symbolic imagery and text. A bird and flying cupids bring flowering branches to a smiling nude woman, a stick figure holds a shovel at the base of one flowering tree, while another flowering tree is flanked by a caterpillar and a butterfly. The style is highly decorative and abstracted in the manner of traditional folk embroidery and painted furniture designs.

Children’s art

Larionov also employed styles associated with children’s art and graffiti, which were considered contemporary manifestations of primitive artistic expression. With its limited palette of vivid primary colors and flat simplified forms, his Soldier on a Horse is reminiscent of crude sign painting and children’s art.

Although it lacks the sophisticated techniques of naturalistic representation, the subject is clearly legible, and the painting effectively conveys the excitement of the rearing horse and the pride of the erect soldier, a nationalistic subject. To emphasize their connection with popular Russian art, Neo-Primitivist artists included the work of children and sign painters alongside their own paintings in the 1913 Target exhibition in Moscow.

Russia’s ancient Scythian roots

Russia’s prehistoric past was also the subject of some Neo-Primitive paintings. Goncharova’s God of Fertility depicts a type of stone funerary sculpture thought to have originated with ancient Scythians (nomadic tribes who roamed Siberia in the first millennium B.C.E.). These mysterious carved stones remained objects of folk superstition and ritual into modern times. Scythian myths and prehistoric pagan rituals were popular subjects for late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century avant-garde Russian music and dance as well. The most famous example is Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, whose primitive rhythms, dissonances and anti-classical choreography caused a scandal at its first performance in Paris in 1913.

In God of Fertility Goncharova again joins a primitive subject to a modern artistic style, using a Cubist technique of faceting to create a non-naturalistic, depthless space in which various symbolic objects associated with fertility float. These include a flower and a horse, the latter referring to the importance of horses in Scythian culture. Abstract geometric forms describe the basic shapes of the ancient sculpture and also suggest that it exists in a space beyond that of the transitory material world.

Promoting Russian modernist primitivism

Neo-Primitivism was an important trend in early Russian modern art, pioneered in large part by Goncharova and Larionov. In addition to producing their own works of modern art, they were organizers of the Jack of Diamonds exhibiting group, which mounted a series of shows of modern European and Russian art in Moscow between 1910 and 1917. The first Jack of Diamonds exhibition showed the French Cubist painters Albert Gleizes and Henri Le Fauconnier alongside Russian artists working in Munich such as Vassily Kandinsky and Alexei von Jawlensky, as well as Russian artists working in Moscow.

In 1912, however, Goncharova and Larionov left the Jack of Diamonds group because they felt it had become too European in its orientation. They mounted The Donkey’s Tail exhibition devoted exclusively to Russian modern art and largely focused on Neo-Primitivism. The artworks nevertheless remained an amalgam of modern and primitive, European and Russian influences. That year, Alexander Schevchenko’s essay “Neo-Primitivism” acknowledged this fundamental contradiction by defining Russian modern art as a hybrid form that had assimilated French avant-garde painting and combined it with the traditional decorative forms of Russian folk art and icons.

Additional resources: