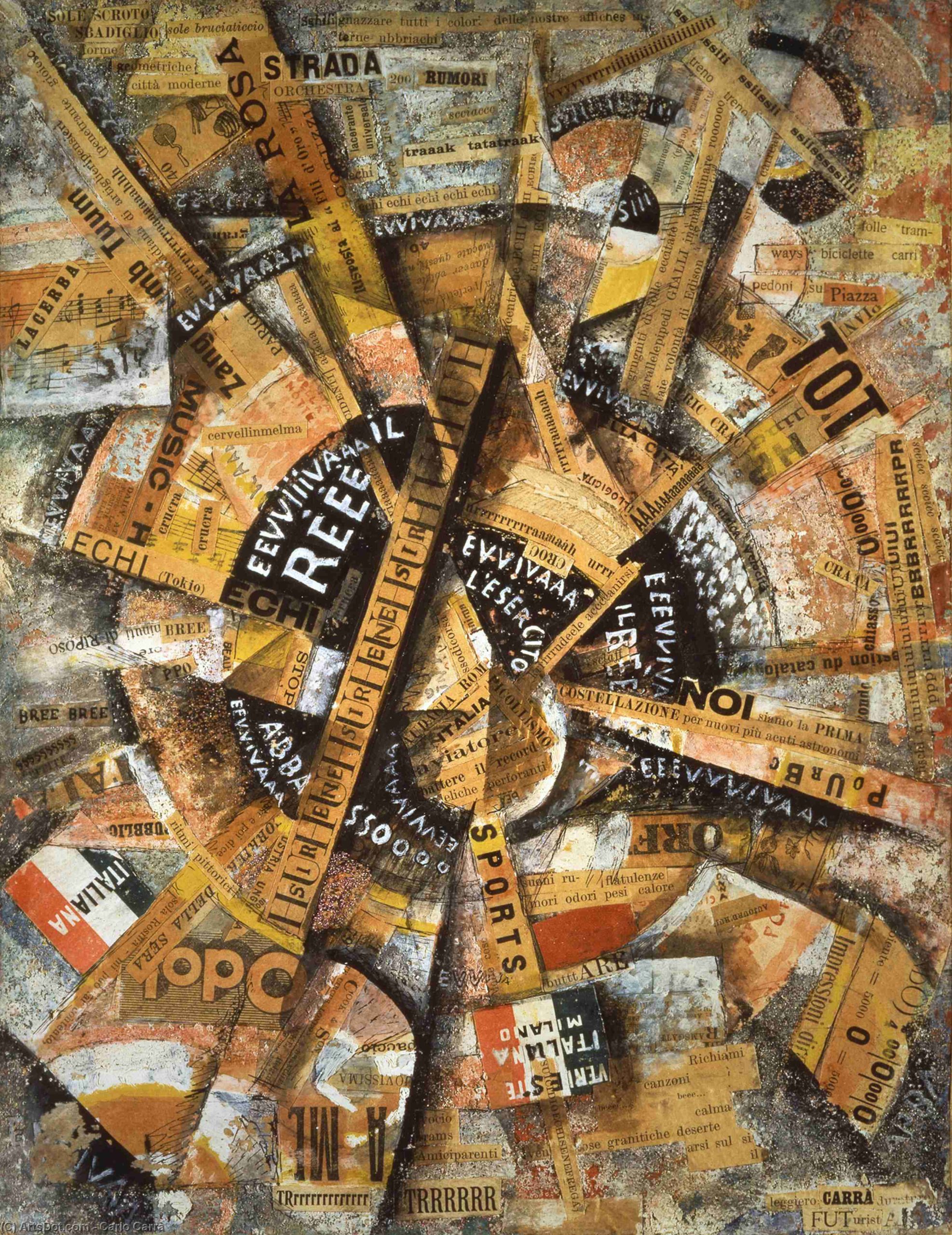

Carlo Carrà, Interventionist Demonstration (Patriotic Holiday – Free Word Painting), 1914, tempera, pen, mica powder, and collage on cardboard, 38.5 x 30 cm (Mattioli Collection, on long-term loan to Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice)

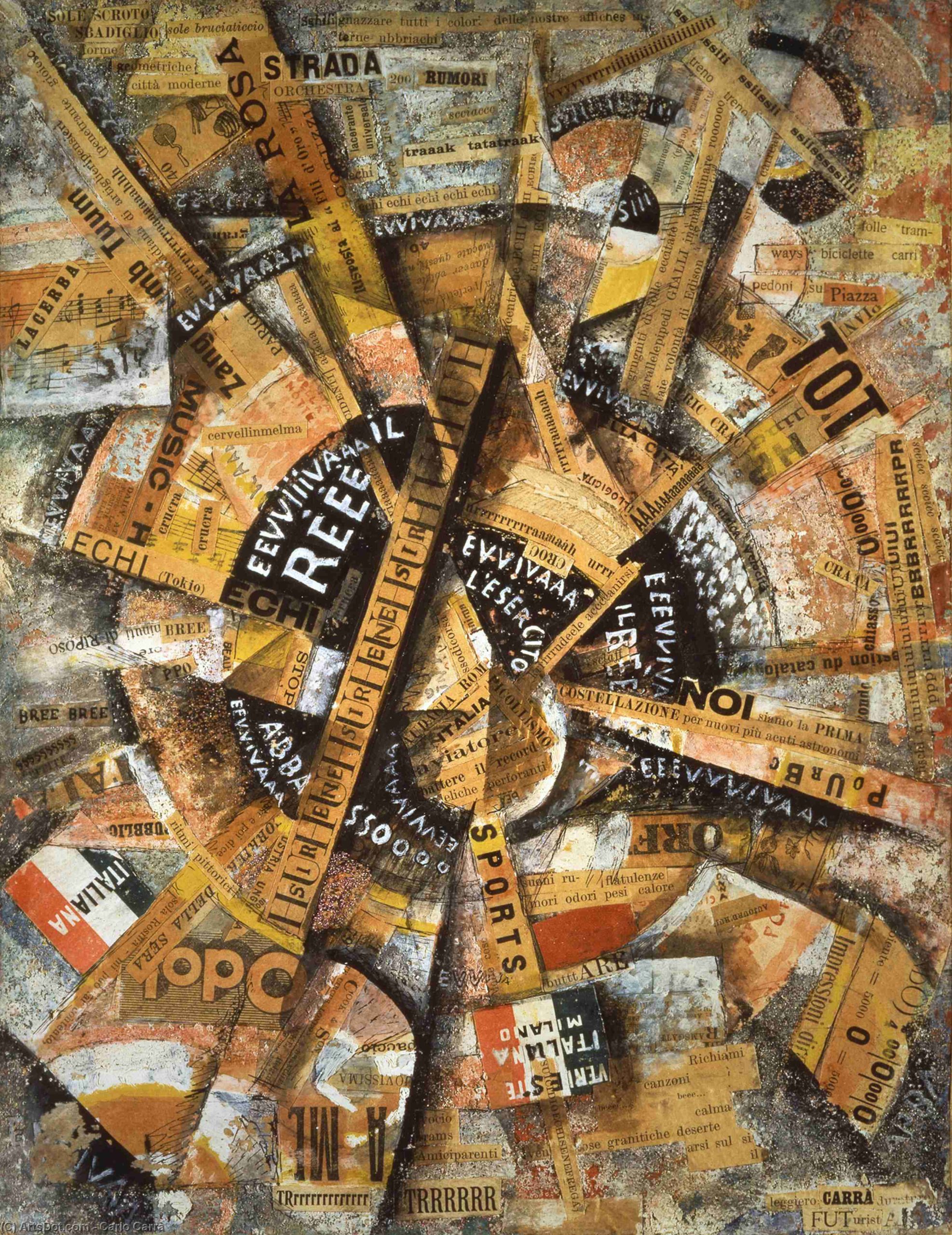

Carlo Carrà, Interventionist Demonstration (Patriotic Holiday – Free Word Painting), 1914, detail, 38.5 x 30 cm (Mattioli Collection, on long-term loan to Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice)

Created in the politically volatile days leading up to World War I, Carlo Carrà’s Interventionist Demonstration (Patriotic Holiday – Free Word Painting) displays both the Italian Futurists’ avant-garde techniques and their militant nationalism. It is a collage painting that uses words as its primary element.

The composition rotates like an airplane propeller, and the word “aviator” is pasted at its heart. Dozens of pasted and painted words fan out from the center like voices shouting in a crowd. There are clippings from advertisements, Futurist poems, and newspaper articles, as well as two painted Italian flags and graffiti-like inscriptions of popular slogans supporting the Italian army and king, and condemning Austria.

Instructions from a propeller

Free word painting is a development of Filippo Marinetti’s parole in libertà — “words in freedom,” often translated as “free word poetry.” Inspired by the intensity of his experiences as a war correspondent in Libya, Marinetti first described parole in libertà as instructions emanating from an airplane propeller. The instructions included the abolition of syntax, punctuation, conjunctions, adverbs, and adjectives. Verbs must be used only in the infinitive form.

These restrictions defined a poetry largely based on conjunctions of nouns intended to directly express things and their physical qualities. For example, a section of Marinetti’s first free word poem Battle of Weight + Smell reads, “20 meters battalions-ants cavalry-spiders roads-fords general-island couriers-locusts sands-revolution howitzers-grandstands clouds-grates guns-martyrs . . .” [1]

A multi-sensory approach

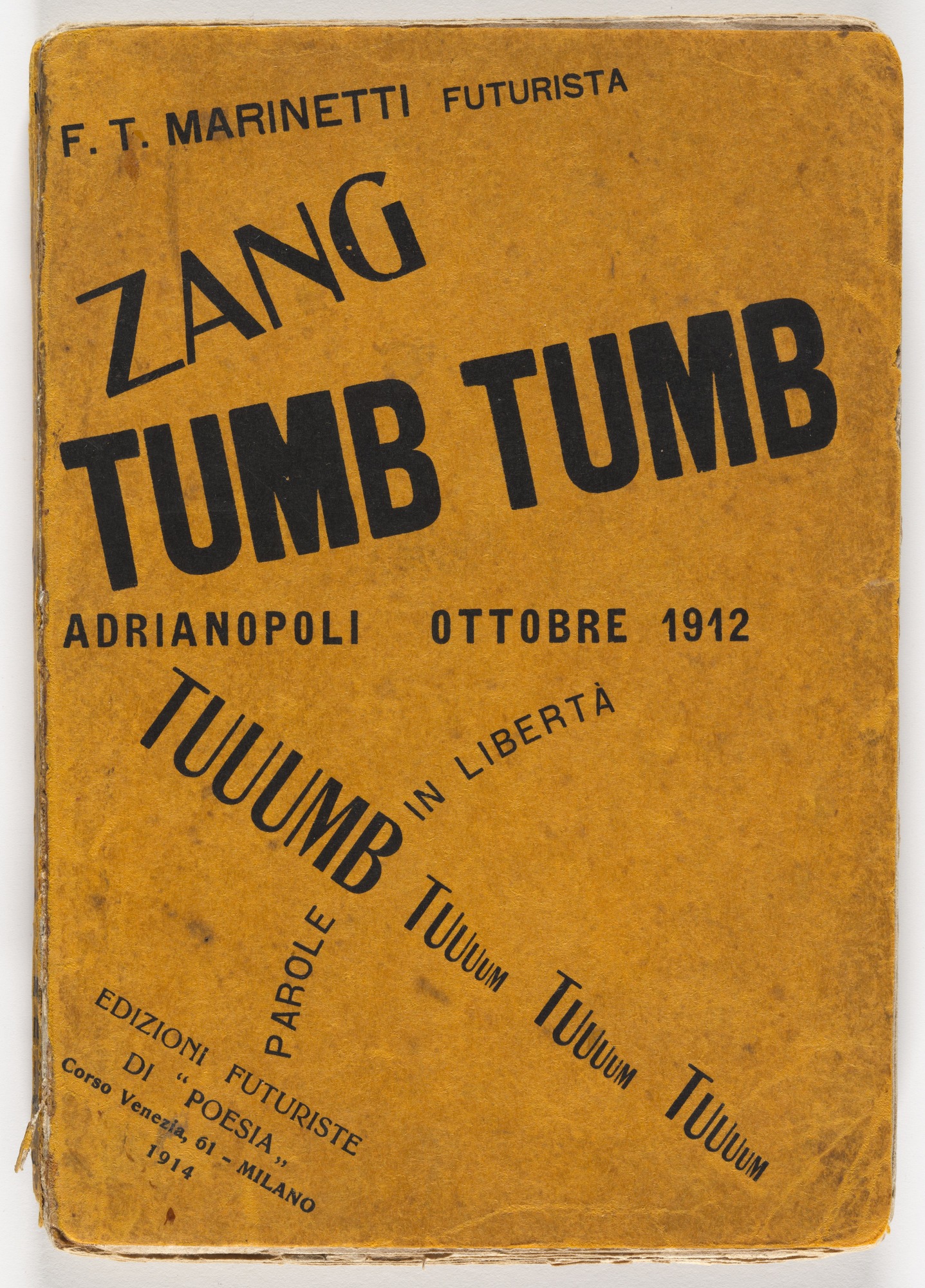

The Futurists developed multi-sensory approaches to communicate the experiences of physical reality. Instead of description, Futurist poets used onomatopoeia to convey sounds directly. The title of Marinetti’s poem ZANG TUMB TUUUM is onomatopoeic; the “words” are the successive sounds of an artillery shell firing, exploding, and reverberating.

In addition to sound, parole in libertà appealed directly to vision and instigated a revolution in typography. The cover of ZANG TUMB TUUUM uses different weights of type to signify the relative volume of different sounds and layout to convey relationships and physical movement. ZANG is on top and angles steeply upward to indicate the firing of the shell. The twice-repeated TUMB is lower and heavier to convey the booming impact of the shell and the power of the explosion. The diminishing echoes of the sonic reverberation are represented below by the steep down-sloping TUUUMBs that shrink with each repetition.

While Futurist poets added concrete aural and visual dimension to their poems, Futurist artists worked to expand the sensory appeal of their works beyond the visual. Carlo Carrà published a manifesto in which he called for painters to express sounds and smells through the use of shape and color. He claimed that all sounds and smells are dynamic vibrating intensities that provoke mental shapes and colors. This is a reference to a well-known perceptual phenomenon known as synesthesia, which can affect people in varying ways. Some people, for example, see colors when they hear music, while others smell a specific odor when they see a particular color. Synesthesia played an important role in the development of abstract painting in the early 20th century, most famously in the theories of Vasily Kandinsky.

Eliminating boundaries

Carlo Carrà, Interventionist Demonstration (Patriotic Holiday – Free Word Painting), 1914, 38.5 x 30 cm (Mattioli Collection, on long-term loan to Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice)

The dynamic arrangement of words in Interventionist Demonstration creates a vortex of expressive significance that sucks the viewer into the composition. There are no still or stable places in the painting. The expanding, radiating composition, along with the inconsistent orientation of the lines of text, suggests that the sounds are coming at the viewer from all sides, dissolving the traditional boundary between viewer and artwork. This was a key goal of the Futurist painters, who wanted to create the sensation of immediacy and aimed to place the viewer in the center of the artwork.

Eliminating boundaries between the senses and between artistic media was also crucial for the Futurists. Carrà intended his painting to communicate emotion directly and synesthetically by means of color, shape, and composition, as well as by words. In addition to political slogans, most of the collaged words are references to Futurist themes, including the city and its crowds, sports and speed, sounds and music, colors and odors. There are numerous violent-sounding onomatopoeic words as well, including the title of Marinetti’s poem ZANG TUMB TUUUM pasted in the upper left.

A twirling dancer

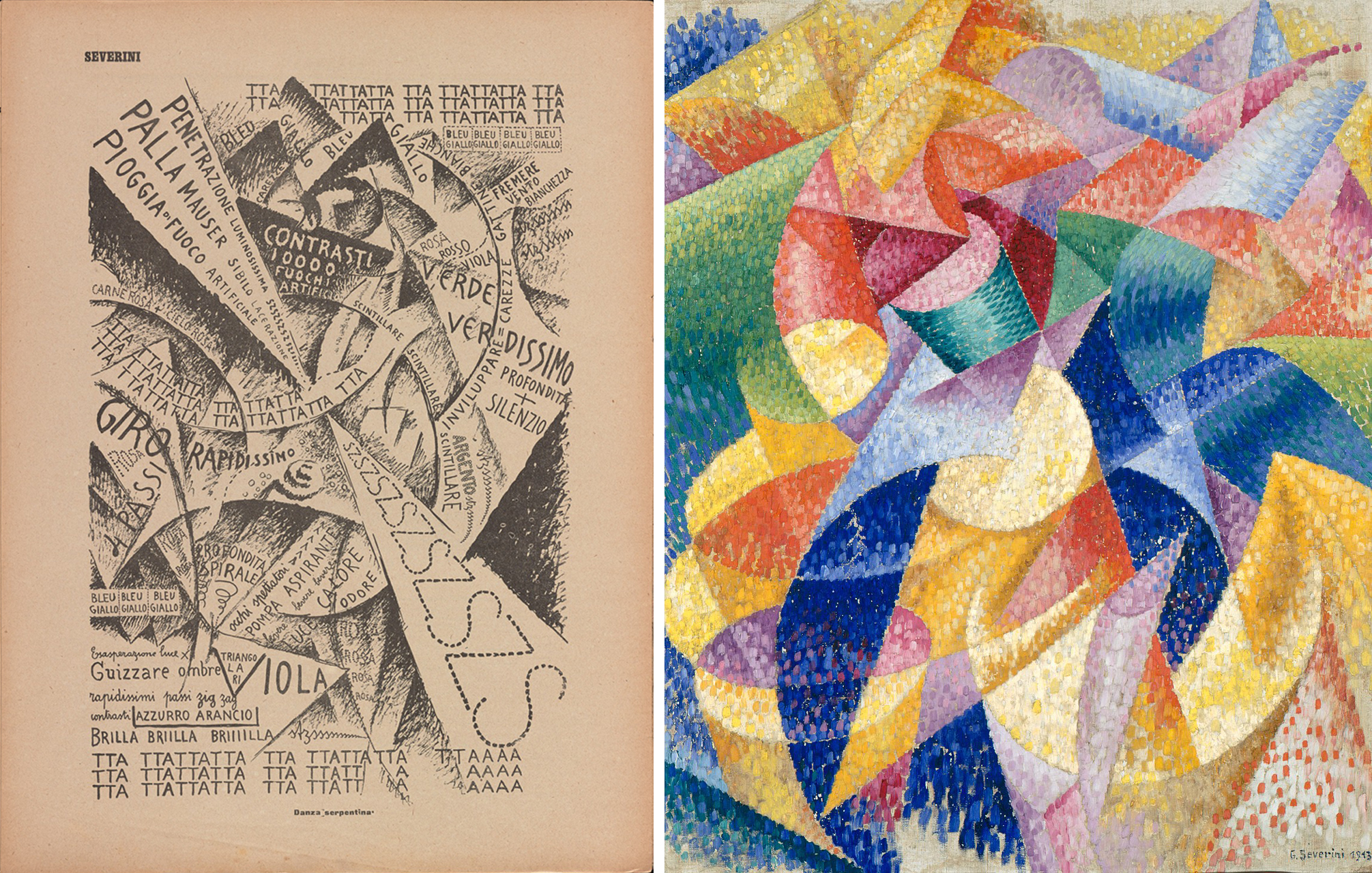

Left: Gino Severini, Serpentine Dancer, in Lacerba (July 1, 1914), p. 202; Right: Gino Severini, Sea = Dancer, 1914, oil on canvas, 39 3/8 x 31 11/16 inches (Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice)

Gino Severini’s Serpentine Dancer uses an approach similar to that of Carrà’s Interventionist Demonstration. It represents the experience of watching a dancer in a nightclub. The abstract composition combines semi-circular arcs accompanied by acute triangles and stark contrasts of black and white. The forms of the drawing are comparable to Severini’s Sea = Dancer, painted only a few months earlier.

Reinforcing the equivalencies of words, sounds, and colors, the drawing includes many names of colors (verde, bleu, giallo, azzurro), as well as onomatopoeic sounds like TTATTA and SZSX. Words of different sizes are woven through the image, creating repeating patterns, echoing shapes in contrasting tones, and contributing both sound and meaning.

Severini indicated the twirling of the dancer with both repeated arcs and the words giro rapidissimo (rapid turn) and profondita spirale (deep spiral). Luce (light), calor (heat), and odore (odor) evoke the sensory experience of being in the nightclub. Piogga di fuoco artificiale (rain of fireworks), palla mauser sililo lacerazione (hissing Mauser pistol shot) and penetrazione luminosissima szszsz (luminous penetration) slash through the image in a white triangle that pierces the heart of the image. They remind us that for the Futurists any mass activity, including the pleasures of nightclubs and dancing, went hand in hand with a desire to incite violence, riot, and war.

On the battlefield

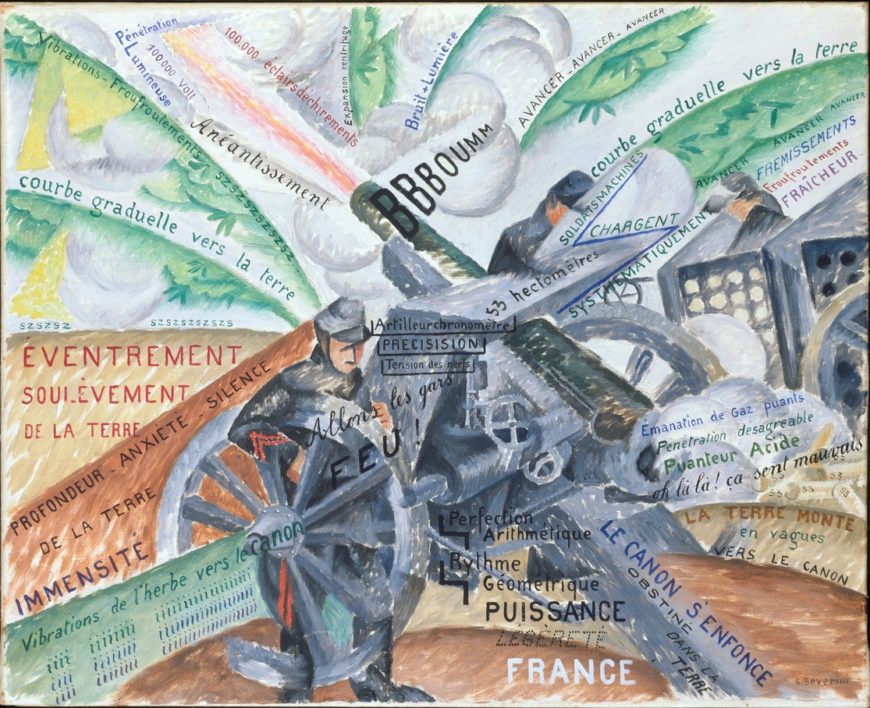

Painted a year later, Severini’s Cannon in Action uses similar techniques to communicate the experience of soldiers on the battlefield in World War I. Rather than representing the twirling of a dancer, this composition explodes out from the center in curves and arcs that convey the power and noise of a cannon firing. In keeping with the Futurists’ love of machinery, a cannon and armored vehicle dominate the scene with soldiers serving as their faceless accessories. Written words follow the painted forms, and most are informational and descriptive, just as the painting is largely representational rather than abstract. For example, the phrases written in the cloud of smoke behind the cannon are all comments on the horrible smell.

Gino Severini, Cannon in Action, 1915, oil on canvas, 50 x 60 cm (Museum Ludwig, Cologne)

The Futurists’ parole in libertà and the development of free word painting arose from their desire to break down the divisions between different art forms to communicate feeling directly. Words, sounds, images, shapes, and colors were all used to convey the intensity of experience and bring the viewer into the heart of the action, be it participating in a crowd in a city square, dancing in a nightclub, or joining artillery men on a battlefield.

Notes:

- Translated in Christine Poggi, In Defiance of Painting: Cubism, Futurism, and the Invention of Collage (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), p. 207.

Additional resources:

Read about “words in freedom” at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum’s Checklist blog

Read Carlo Carrà’s manifesto, The Painting of Sounds, Noises, and Odors

Read Filippo Marinetti’s Technical Manifesto of Futurist Literature