President Reagan giving a speech at the Berlin Wall, June 12, 1987 (photo: Reagan White House Photographs, CC0)

“Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!”

— U.S. President Ronald Reagan

When Ronald Reagan addressed these words to Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in June of 1987, few believed that just two years later the Berlin Wall would actually be dismantled. It seemed like a permanent fixture, symbolizing the irreparable divide between the Cold War powers. But by 1990, all but a few traces of the wall were gone.

Map of post-WWII Germany divided between the Allied Powers (adapted by Dr. Naraelle Hohensee from WikiNight2, GNU Free Documentation License)

Dividing a nation and a city

After Germany’s defeat in World War II, the Allied Powers each took control of a section of the country. By 1949, two Germanys emerged from this occupation. The Federal Republic of Germany (commonly known as West Germany) was an independent, democratic nation formed out of the British, French, and American zones. The German Democratic Republic (or GDR, commonly known as East Germany), was a socialist state under the leadership of the Soviet Union.

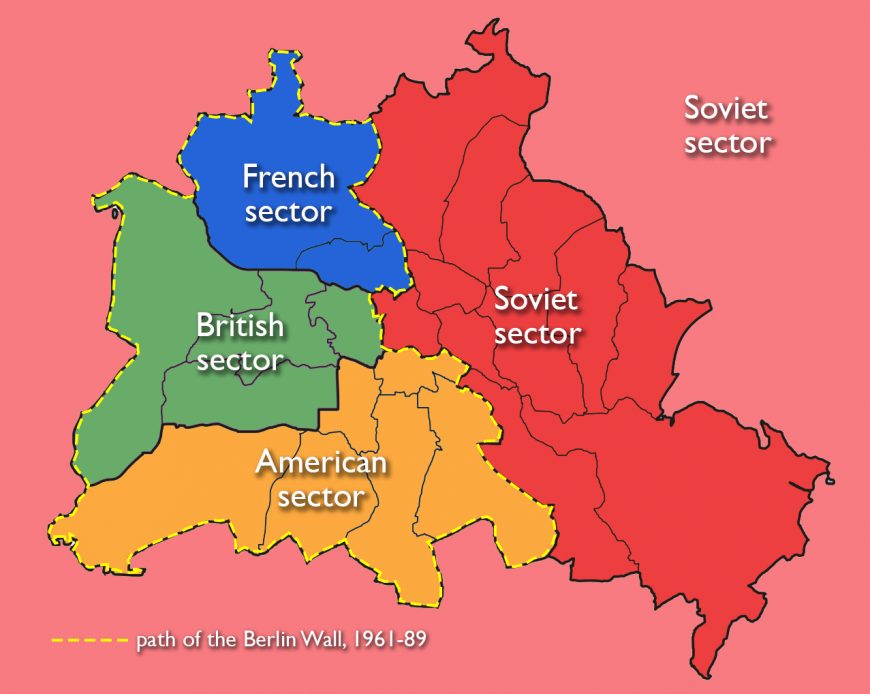

Map of the four post-WWII sectors of Berlin and the future path of the Berlin Wall (map adapted by Dr. Naraelle Hohensee from Paasikivi, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Berlin lay deep within what became East Germany, but as the former capital of Hitler’s empire, it received special treatment. The city itself was divided between the four Allied powers after the war, and so it, too, was divided into two parts once East and West Germany were created. East Berlin remained the capital of the GDR, while a new West German capital was established far to the west, in Bonn. West Berlin, formed from the British, French, and American sectors of the city, effectively became a tiny West German outpost in the midst of East Germany.

It may be surprising to learn that during the first decade after the country’s division, the border between East and West Berlin remained completely open. Aside from using different currencies, East and West Berlin were relatively indistinguishable—city trams still ran between the two halves, and people could visit friends and relatives on the other side of the city.

Traffic between West and East Berlin passes through the Brandenburg Gate, 1959 (photo: German Federal Archives, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Outside of Berlin, though, the differences between the two countries were becoming increasingly stark. West Germany experienced an “economic miracle” or “Wirtschaftswunder” thanks to subsidies from the Western powers, while East Germany struggled economically. Over the course of the 1950s, several million people chose to leave for West Germany to seek jobs and a better quality of life. In response, the East German government—afraid of losing its labor force, but also ashamed of the increasing tide of emigration—imposed continuously stricter limits on travel.

As leaving East Germany became increasingly difficult, West Berlin, with its open internal border to East Berlin, remained one of the only exit routes for those who wished to emigrate. It also operated as a “show-window for the West” (that is, a beacon of Western consumerism and liberal democracy placed prominently alongside the capital of communist East Germany). Most importantly, Berlin was a major site of political confrontation between the United States and Soviet Union, whose leaders were threatening one another with nuclear war. The city became a heated microcosm of Cold War politics.

The border that would become the Berlin Wall, constructed with barbed wire, in August, 1961 (photo: Helmut J. Wolf, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Constructed overnight

On the morning of August 13, 1961, Berliners awoke to find that overnight, soldiers had used barbed wire to completely close the border between the two halves of the city—catching almost everyone by surprise. No warning had been given: trams stopped in their tracks, people headed to shop or visit friends on the other side of the city were turned back, and deadly force was employed to keep people from crossing. Over the next 25 years, the GDR fortified this border by erecting a series of solid walls and barbed-wire barriers, as well as a “death strip” of cleared land with tripwires and mines, all to prevent people from escaping. Over the next four decades, more than 140 people were killed in connection with the Berlin Wall.

The Berlin Wall not only prevented people from moving across the city—it also fundamentally changed how the two halves of the city functioned. Systems like water, electricity, sewer, and public transportation had to be separated. [1] Because the Berlin Wall went through the center of the city, urban development on each side began to focus elsewhere. What had been the city’s glittering, historic baroque city center was now located on the western outskirts of East Berlin, along the wall. It became virtually a forgotten wasteland, as new centers sprang up to the east and west.

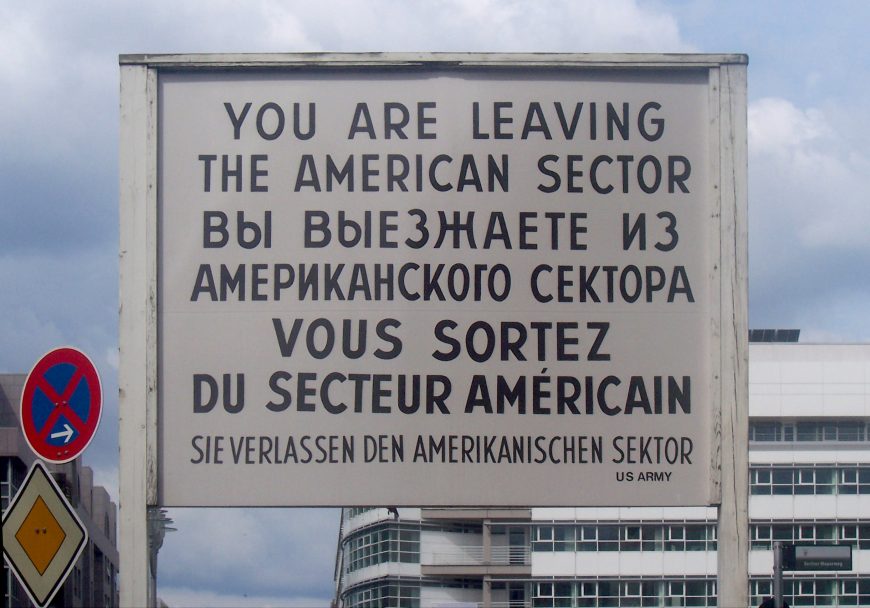

The sign at Checkpoint Charlie announcing the border between the American and Soviet sectors (East and West Berlin), now preserved as a memorial (photo: Henry Robbert, CC0)

A political symbol

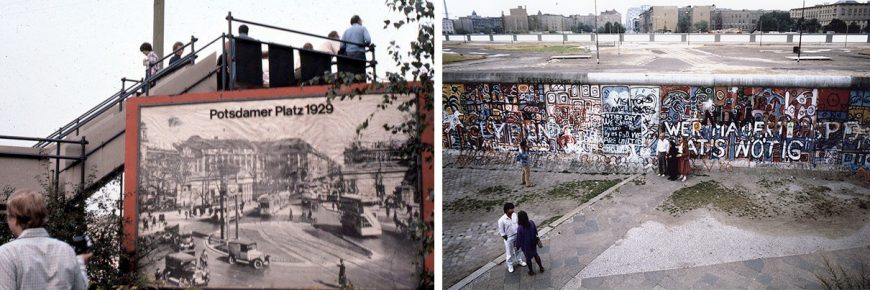

Over time, particular points along the Berlin Wall became well-known symbols of the division. Checkpoint Charlie, a border crossing between the former American and Soviet regions of the city, was famous for its sign that boldly stated, “You are leaving the American sector.” The section of wall in front of the Brandenburg Gate, Berlin’s monumental baroque triumphal arch, was also often photographed. Potsdamer Platz, which had been a busy commercial center during the Weimar years but was left barren and desolate after heavy bombing in World War II, was one of the largest open areas next to the Berlin Wall. The viewing platform that was installed there on the western side became a popular destination for tourists.

Left: the viewing platform on the West Berlin side of Potsdamer Platz, 1977, with a billboard displaying a photo of the site in 1929 (photo: BeenAroundAWhile, CC BY-SA 3.0); right: the view over the Berlin Wall, with West Berlin tourists in the foreground, 1986 (photo: Nancy Wong, CC BY-SA 3.0)

These often-photographed sites functioned as both objects of curiosity for Westerners, and symbols of the cruelty and repression imposed by the GDR and the Soviet Union. Their nearness to democratic West Berlin brought the Cold War conflict home: as opposed to wars happening “elsewhere” (such as the proxy wars that the United States and USSR were fighting in Vietnam and Afghanistan), this one was taking place on the doorstep of Western Europe.

The Berlin Wall also became a potent symbol through the art that appeared on its western side. As a political outpost, West Berlin became a place that many social radicals and artists called home. In the late 1970s and 1980s, the East German government replaced the hodge-podge of barriers that had been constructed over the years with a single, more defensible, 12-foot-high wall. The western side of this new enclosure provided the perfect surface for graffiti, and street artists from around the world flocked to Berlin to make their mark on it.

Thierry Noir murals, left: Berlin Wall, 1985 (photo: Thierry Noir, CC BY-SA 3.0); right: section of the Berlin Wall displayed in New York City (photo: Ronny-Bonny, CC BY 3.0)

Thierry Noir is one of the best-known artists to have painted the Berlin Wall in the 1980s. Today he continues to produce murals in his signature style, often featuring cartoonish, elongated heads with enlarged lips, on the remaining pieces of the Wall and elsewhere. Well-known international artists like Keith Haring also created murals on the Berlin Wall during this time.

Graffiti on the Berlin Wall was only visible to those on the West Berlin side. In East Germany, it was officially called an “Antifaschistischer Schutzwall,” or “anti-fascist protection barrier.” Despite the fact that those who tried to cross this border were killed or imprisoned and tortured, GDR propaganda claimed that the Berlin Wall was not a way to keep East Germans in, but a way to keep the forces of fascism out. Because even approaching the wall was dangerous, most East Berliners chose to ignore its existence in their daily lives.

People atop the Berlin Wall near the Brandenburg Gate on 9 November 1989. The text on the sign “Achtung! Sie verlassen jetzt West-Berlin” (“Attention! You are now leaving West Berlin”) has been modified with the additional handwritten “Wie denn?” (“How?”) (photo: Sue Ream, CC BY 3.0)

The fall of the wall

Throughout the 1980s, the Soviet Union gradually loosened many of its policies as well as its control over the countries behind the Iron Curtain. By 1989, Hungary (also a Soviet satellite state, like East Germany) had opened its border, allowing a path for thousands of East Germans to leave for the West. Protests against the Communist government began to take place throughout East Germany. Finally, on November 9th, officials rather abruptly announced that the border between East and West was open—effective immediately.

East Germans drive through Checkpoint Charlie after the fall of the Berlin Wall, 1989 (photo: Staff Sergeant F. Lee Cockran, CC0)

The news was broadcast across Germany and the world, and with a combination of euphoria and bewilderment, East Berliners streamed through the checkpoints, greeted by jubilant West Berliners. Soon, people began hacking away at the wall, and its “fall” became yet another Cold War symbol: this time of the fall of the Iron Curtain.

“Mauerspechte” chip off pieces of the Berlin Wall, December 1989 (photo: Aad van der Drift, CC BY 2.0)

Within a year, most of the Berlin Wall had been dismantled and sold—either unofficially, by “Mauerspechte” (“wall-peckers”), who chipped off pieces as souvenirs, or by the bulldozers and cranes of the East German government. The two halves of the nation and its capital city were legally reunified the following year, on October 3, 1990. [2]

A double row of cobblestones now marks the former route of the Berlin Wall in front of the Brandenburg Gate (photo: Wici, CC0)

Where is the Berlin Wall?

Thirty years after its fall, the Berlin Wall is still the landmark most visitors look for when they come to Berlin. Most of the barrier has been erased from the urban landscape, but a few remaining sites pay tribute to its existence. The city of Berlin installed a line of double cobblestones in the ground to mark the wall’s former route.

A preserved Berlin Wall border strip at the Berlin Wall Memorial on Bernauer Straße, Berlin, photographed from the viewing tower in the memorial documentation center (photo: Domaine public, CC0)

Informational boards and memorial markers have been installed throughout the city center to explain the history of the wall and honor those who died trying to cross it. Just north of the city center, one strip of the border system has been carefully preserved, including a guard tower and a “death strip,” accompanied by a small museum and information center.

East Side Gallery, Berlin (photo: Freepenguin, CC BY-SA 3.0)

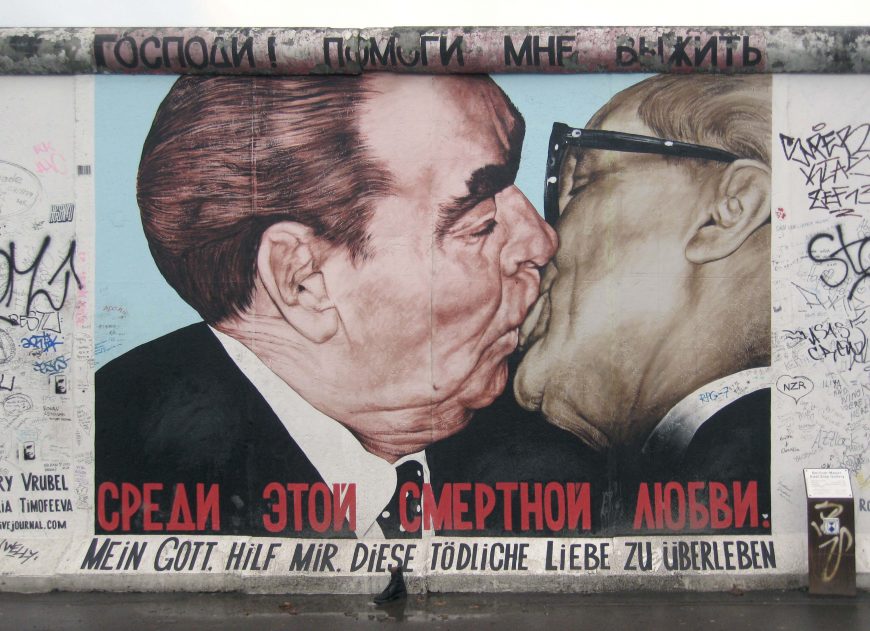

By far the most visible and most frequently visited piece of the wall in Berlin today is the East Side Gallery, a long strip of the wall covered in murals. Located at the end of the former East Berlin neighborhood of Friedrichshain, it stretches along the Spree River for over 1.3 km (0.8 miles). It was painted by a collaborative of international artists in 1990 on its eastern side (hence the name “East Side Gallery”) shortly after the opening of the border. (Painting on this side would not have been allowed when the GDR existed.) This section of the Berlin Wall was landmarked in 1991, though vandalism and development have had an impact. [3]

Dmiti Vrubel, Mein Gott, hilf mir, diese tödliche Liebe zu überleben (My God, Help Me to Survive This Deadly Love), original created 1990, East Side Gallery, Berlin (photo: Pelorucho, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Several of the East Side murals (there are currently 101) have become especially famous. My God, Help Me to Survive This Deadly Love by Russian artist Dmitri Vrubel is based on a photograph of USSR and GDR leaders Leonid Brezhnev and Erich Honecker kissing each other on the lips. The mural at first shocks many viewers with its large-scale portrayal of two older men locked in a seemingly romantic embrace. This “fraternal kiss” had taken place in 1979, on the 30th anniversary of the GDR. The image alludes directly to the political intimacy between East Germany and the Soviet Union, while the title of the painting, appearing above and below the figures in Russian and German, adds a critical or satirical tone to the piece: who is hoping to “survive,” and why is this love “deadly”? One might surmise that the words are the voice of East Germany, for whom a relationship with the Soviet Union was ultimately both politically and economically destructive.

Birgit Kinder, Test the Best, 2009 version (detail), originally created 1990, East Side Gallery, Berlin (photo: Lorena a.k.a. Loretahur, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Another famous East Side Gallery mural is Birgit Kinder’s Test the Best, which depicts an East German Trabant (virtually the only brand of car available in the GDR) breaking through the Berlin Wall. Kinder painted a companion mural depicting the back of the car on another section of the Wall, which is now preserved in the State Ministry for the Environment.

Perhaps the most lasting, and problematic, legacy of the Berlin Wall is not physical at all, however. It is the so-called “Wall in the Head” that still separates former East Germans (“Ossis”) from West Germans (“Wessis”). The former East is still plagued by high unemployment and poverty today. Though Berlin has been put back together, the ongoing social and economic division between the two halves of the country has yet to be healed, and the Berlin Wall remains an important symbol for both the history and future of the nation, Europe, and the world.

Notes:

- The two cities had been gradually separating their systems of governance as well as services (like police departments) and infrastructure (phone lines and transportation) since the end of the war, but the construction of the Wall in 1961 required that this process be swiftly and thoroughly completed.

- After East and West Germany reunited, it was still not clear whether the capital of the nation would be located in Bonn or Berlin. The parliament voted to locate the new capital in Berlin in 1991.

- The artists of the murals that make up the East Side Gallery have had to make numerous requests for additional funds from the city to clean and restore the murals because of frequent vandalism, and nearby development has resulted in the demolition of a few parts of the wall.

Additional resources:

Information on the Berlin Wall and its memorials from the city of Berlin

Keith Haring’s mural on the Berlin Wall

Thierry Noir’s account of painting the Berlin Wall

Photographs of the Berlin Wall in the 1980s by Edward Murray

Website of the East Side Gallery

An overview of Berlin history from Berlin.de

Emily Pugh, Architecture, Politics, and Identity in Divided Berlin (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2014)

Brian Ladd, The Ghosts of Berlin (University of Chicago Press, 1998)

Janet Ward, Post-Wall Berlin: Borders, Space and Identity (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011)