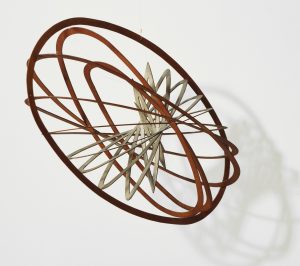

Aleksandr Rodchenko, Spatial Construction no. 12, c. 1920, plywood, aluminum paint and wire, 24 x 33 x 18.5” (MoMA)

Aleksandr Rodchenko’s Spatial Construction no. 12 is one of a set of three-dimensional geometric forms generated by a simple iterative process. It began as a sheet of plywood cut into an ellipse. Rodchenko then made a second cut following the edge of the first to create a narrow oval ring. He continued cutting ever smaller rings until reaching the center.

Once cut, the rings were fanned out into three dimensional forms held in place by wire. They were covered with aluminum paint and suspended from the ceiling for exhibition, along with similar constructions cut from a square, a circle, a triangle, and a hexagon. These visually complex sculptures created by a simple process were the result of the Russian Constructivists’ goal to create rationally-produced objects based on fundamental laws of form and structure.

Constructing a new art for a new Russia

The Constructivists were a group of avant-garde artists who worked to establish a new social role for art and the artist in the communist society of 1920s Soviet Russia. They were committed to applying new methods of creation aligned with modern technology and engineering to art, and eventually to utilitarian objects. Their overall approach was theoretical and scientific, and they rejected the stereotype of the artist as intuitive and inspired.

They made a distinction between composition, which resulted from the artist’s intuition, and construction, based on scientific laws. Rodchenko’s Spatial Constructions were examples of the latter, forms structured by logical deduction, not intuition. They were considered “lab work” rather than art objects and were made to demonstrate theoretical concepts.

Structure as form

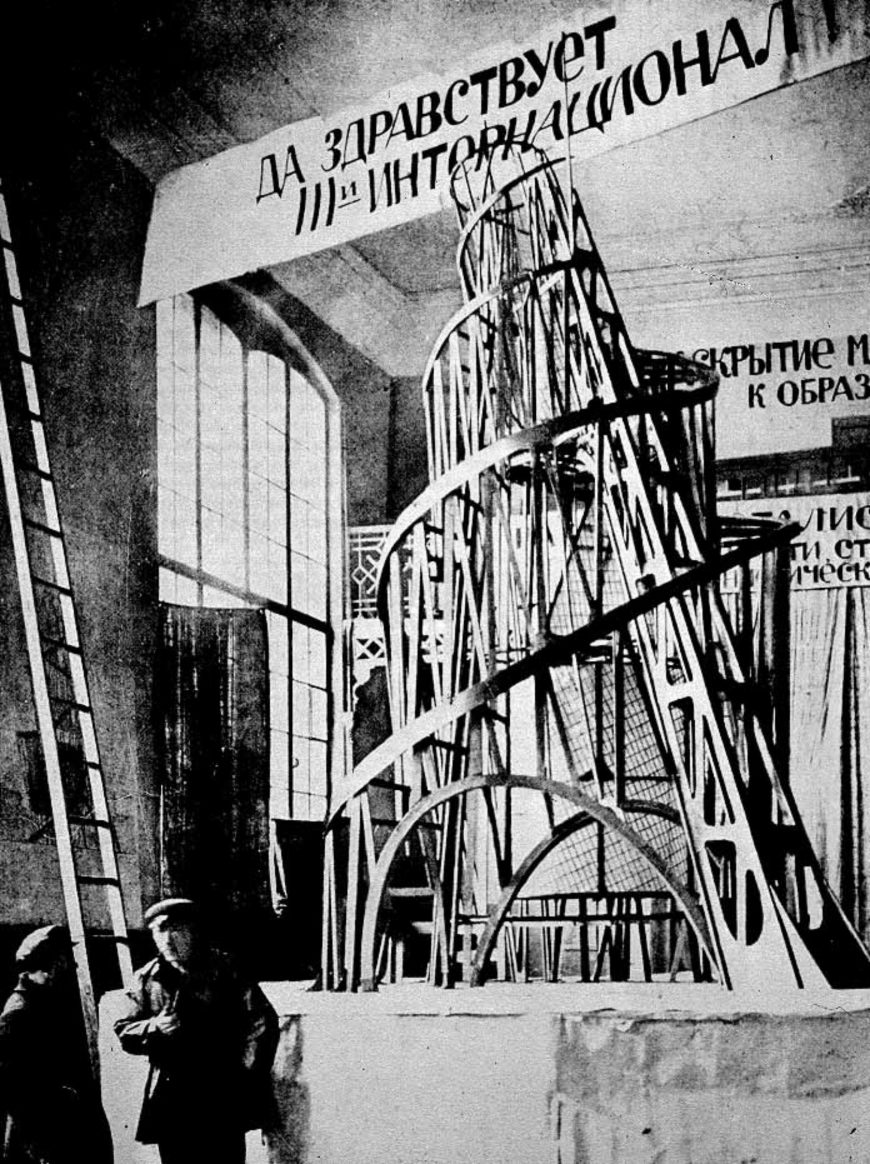

Very few early Russian Constructivist works have survived, but the photograph of the Obmokhu (Society of Young Artists) exhibition where Rodchenko displayed his Spatial Constructions in 1921 shows a variety of Constructivist works. Most use simple geometric forms and straight lines, a visual language that suggests the basic structural units of modern engineering and architecture.

In two-dimensional works, paint strokes and free-hand drawings were replaced by lines and shapes created by ruler and compass. Most of the three-dimensional works were made of wood, but they have uniform smooth surfaces suggesting machine-made forms rather than textures created by the artist’s hand. As noted above, Rodchenko’s Spatial Constructions were covered with aluminum paint, and it is likely that they would have been made of metal if that had been feasible.

The visual language of many Constructivist works signifies the modern machine age in terms of structure as well as surface. Rodchenko’s hanging Spatial Constructions were dynamic forms with visible structures, rather than static sculptural masses on pedestals. The interest of the work lies, in part, in the way it demonstrates a system. Rodchenko’s Spatial Constructions create complex shifting patterns of solid planes, spaces, and shadows, but their basis is a simple, easily-grasped rational system. Recognizing the way this rudimentary system generates complex visual experiences is part of the works’ aesthetic pleasure.

Konstantin Medunetsky, Spatial Construction (Construction no. 557), 1919, tin, brass, painted iron and steel, 46 x 17.8 x 17.8 cm (Yale University Art Gallery)

Materials and faktura

Konstantin Medunetsky’s Spatial Construction was also in the Obmokhu exhibition, but it displays different concerns from Rodchenko’s works. Instead of demonstrating a rational construction system, Medunetsky’s work displays contrasts between shaped metals. A tin S-curve, a steel circle, a brass triangle, and a red-painted iron parabola are interwoven and welded to a painted metal cube. The work is strikingly modern in its abstract formal language and its machine-age materials.

Vladimir Tatlin, Counter-Relief, 1913, wood, metal, leather (The State Tretyakov Gallery)

The different shapes of the metals demonstrate their material properties: the thin S-curve shows the great flexibility of tin; the thin triangle plate of brass highlights its qualities as a surface material; the heavy steel ring showcases its strength and flexibility; while the red-painted iron parabola is the stabilizing, unifying, and dynamic force of the composition. It also has symbolic references; it is like both a handle and an arrow pointing upward to the communist future, signified by the brilliant red paint.

The juxtaposition of different materials in Medunetsky’s work reflects the Constructivist concept of faktura. Faktura was a much-debated term among Russian modernists in the first decades of the twentieth century that signaled a focus on the texture and working qualities of materials.

Vladimir Tatlin’s Counter-Relief is an example of a modern sculpture that was seen as primarily concerned with faktura. It is a non-representational sculptural assemblage of various found materials displayed in ways that demonstrate their properties. The wood, pitted and discolored with age, acts as a tack board for the other elements, including coarse-grained leather stained with different dyes and various types of metal with contrasting colors and sheens.

Each material is manipulated in ways that display its working qualities: the soft elasticity of the leather tacked to the upper half, and the stiff flexibility of the metal as it is bent into curved planes and twisted into a wire corkscrew.

Traditional Western sculptors such as Michelangelo or Bernini had generally attempted to transcend their materials: to make marble appear to be flesh or cloth. The philosophy of faktura was, on the contrary, to understand and display the fundamental properties of materials.

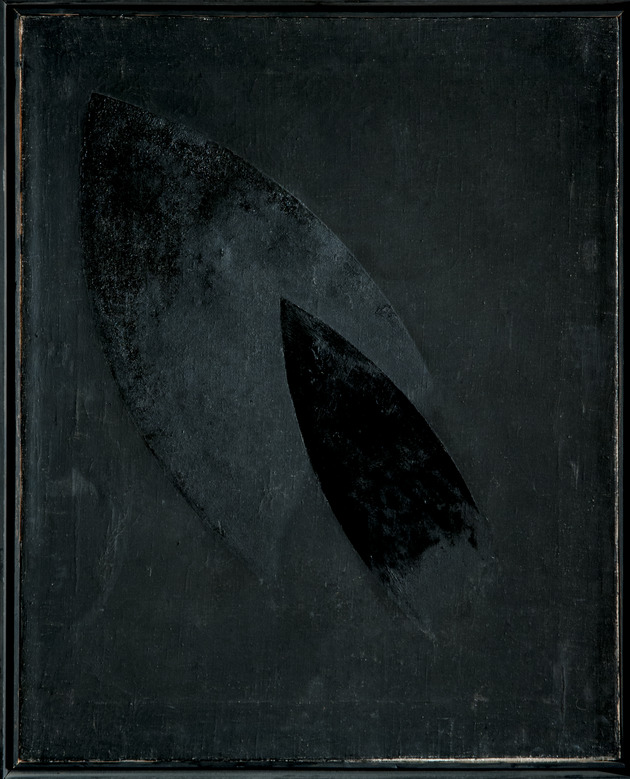

In 1918 Rodchenko made a number of paintings that demonstrate pure faktura; their surfaces were simply black paint applied to canvas in varied textures to create shapes. The paintings were made as a challenge to the white Suprematist paintings of Kasimir Malevich, which used white geometric forms as a means of spiritual communication. In contrast, Rodchenko’s black paintings made no reference to anything other than their material qualities.

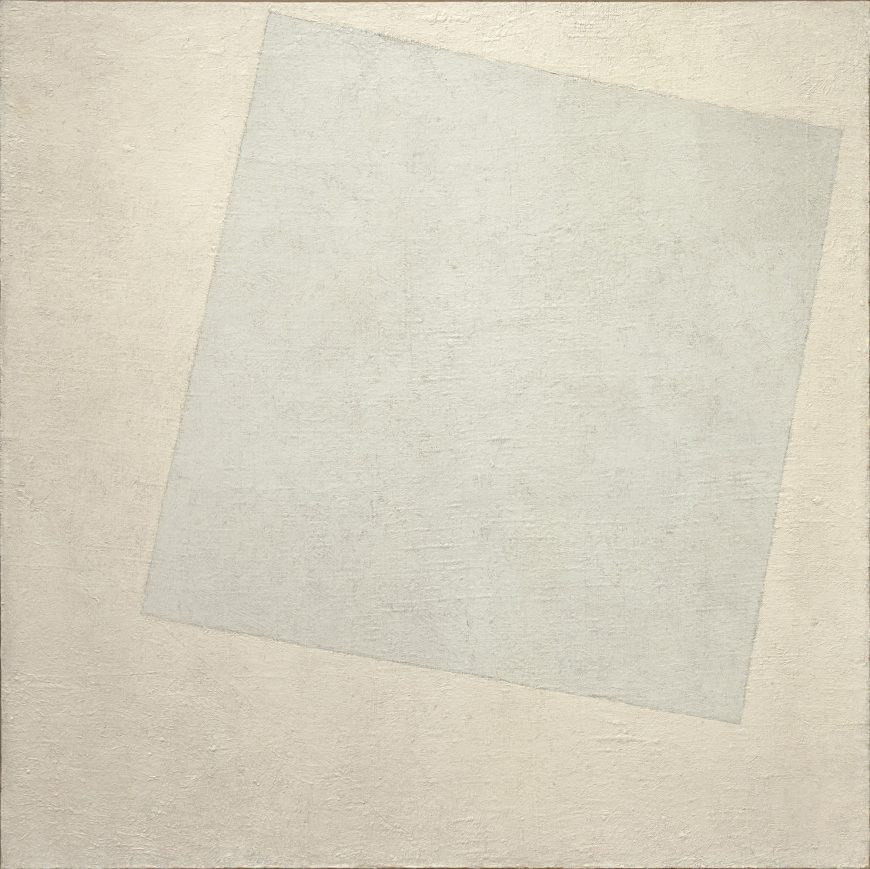

Kasimir Malevich, Suprematist Composition: White on White, 1918, oil on canvas, 79.4 x 79.4 cm (MoMA)

The end of artistic intuition

Rodchenko’s challenge to Malevich’s Suprematism illustrates one of the essential tenets of Constructivism: the rejection of old conceptions of art and the artist. Despite his radical invention of pure geometric abstraction, Malevich was what the Constructivists considered an outdated and bourgeois artist. He was an individualist who believed that he created his art intuitively. In addition, Malevich was an idealist dedicated to a spiritual world and an art that communicated transcendental meanings and emotions. The Constructivists, in line with Communist tenets, rejected spiritual concerns in favor of the material world and laws determined by scientific means. The Constructivists’ “lab works” in the 1921 Obmokhu exhibition displayed their approach to making impersonal and scientifically-grounded forms that had no significance beyond their material existence as physical examples of rational systems.

Synthesizing art and engineering

The work of Vladimir Tatlin was a major touchstone for the Constructivists. His Monument to the Third International, a model for a structure intended to house Communist Party functions, was a paradigm of the Constructivists’ efforts to synthesize art and engineering to create modern utilitarian forms for the new era. Tatlin himself, however, rejected the Constructivists’ dedication to the scientific production of works. Although his art was not engaged with spiritual concerns, as Malevich’s was, he believed the artist’s intuition could not be replaced by scientific laws.

After the 1921 Obmokhu exhibition the Constructivists left their theoretically-oriented lab works behind and became dedicated to utilitarian production. Their abstract formal ideas helped to shape designs for furniture and clothing, posters and theatrical productions, architecture and even manufacturing techniques. This turn to utilitarian projects was motivated in large part by the requirements and expectations of Soviet society and the massive drive to modernize and industrialize the country.

The Constructivists’ theories and ideas also became part of international conversations about the fundamental elements of art, designing for the modern world, and the education of artists. Another major focus for these debates was the German Bauhaus, and they resonated across the 20th century and continue to this day.

Additional resources:

Christina Lodder, Russian Constructivism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983).

The Great Utopia: The Russian and Soviet Avant-Garde, 1915-1932 (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1992).