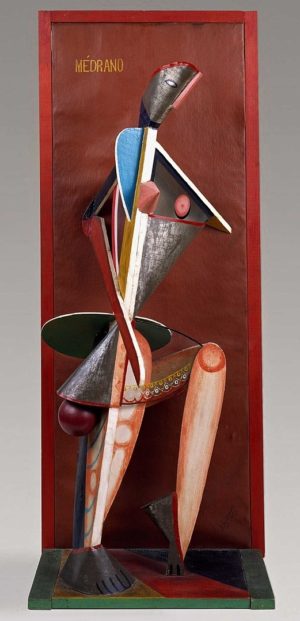

Alexander Archipenko, Médrano II, 1913, painted tin, wood, glass and oil cloth, 49 7/8 x 20 ¼ x 12 ½ inches (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York)

Cubism instigated significant developments in twentieth-century sculpture, challenging the European sculptural tradition in terms of form, media, and often subject matter. Alexander Archipenko’s Médrano II is an early example of the new approaches used by Cubist sculptors.

A circus performer

Médrano II is a representation of a woman made from simple shapes in a variety of materials. She looks like a jaunty doll dancing on a shelf. Her head is a piece of folded tin with a painted eye and red hairline and a thin piece of pink wood for a nose. A central wooden vertical supports glass, tin, and wood planes, which are cut into basic geometric shapes and painted in bright colors to represent her shoulders, arms, legs, and skirt. Two simplified wooden feet anchor the figure on a multicolored horizontal plane that projects like a shelf from a vertical red backdrop that frames the figure.

The title refers to the Médrano circus, which was frequented by many artists in the early 20th century, and indicates that the brightly painted figure is a circus performer. Her mobile stance with one leg bent on tiptoes and the inclusion of a ball below her skirt suggests the lighthearted attitude of an acrobat or juggler. The forms of Archipenko’s sculpture are similarly playful with repeated circles that seem to bounce through the figure, as well as the delicate pattern painted on the glass skirt, through which we can see the woman’s thigh.

Sculptures that hang from the wall

Médrano II is a rare surviving early Cubist sculpture that reflects the innovations of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque’s Synthetic Cubist collages and sculptures. Like them, Archipenko combines a variety of cheap materials, emphasizes repeated geometric shapes, and adopts a playful approach to representation and design. The presentation of the sculpture against a framing backdrop is also similar to Picasso’s early Cubist sculptures, which were frequently conceived as hanging from the wall like paintings. The subject of a female figure and the bright colors are, however, more comparable to the approaches used by the Salon Cubists, and Médrano II was, in fact, exhibited in the 1914 Salon des Indépendants.

Henri Laurens, Head of a Woman, 1915, painted wood, 20 x 18 ¼ inches (MoMA)

Henri Laurens’ Head of a Woman also uses a Cubist assemblage technique, but it is a more abstract and formally ambitious work than Archipenko’s. Like the later Cubist paintings and collages of Braque and Picasso, the head is fractured into multiple abstract shapes that represent specific features by relationship and form. For example, we can recognize the central vertical white triangle as a nose and the white circle next to it as an eyeball, while zigzag edges in the plane above suggest hair. The sculpture successfully translates the ambiguities of Cubist representation into three dimensions; however, it was made to hang on a wall, and thus intended to be viewed from a restricted angle. Like Archipenko’s Médrano II, it does not exploit the full potential of sculpture’s three-dimensionality.

A more traditional approach

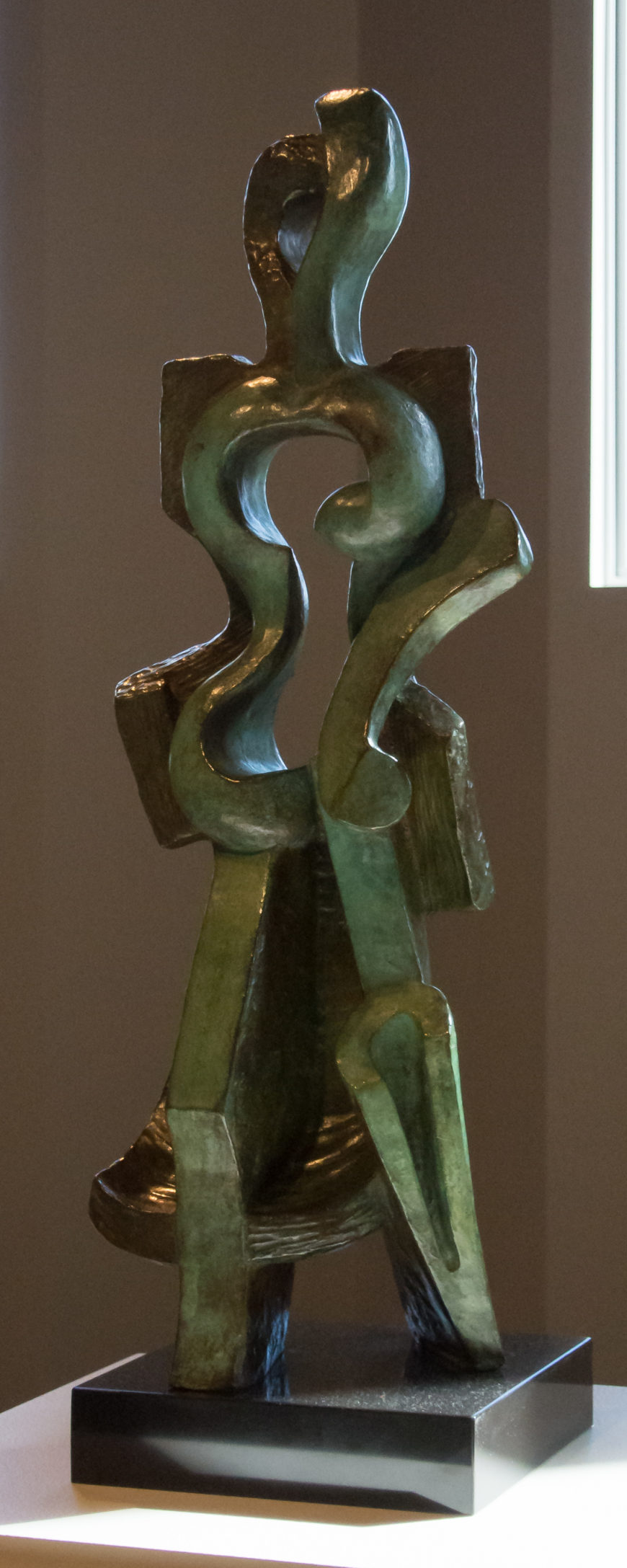

Alexander Archipenko, Walking Woman, 1912, bronze, 30 ½ x 9 ¾ x 8 ½ inches (Denver Art Museum) (photo: mark6mauno, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Archipenko also created several small freestanding bronze Cubist sculptures of women. In terms of medium, these were much more traditional than his Médrano II. They did, nevertheless, fully translate the Cubist approach into the three dimensions of sculpture. Walking Woman breaks down the mass of the body and incorporates space into the center of the form. The solid elements of the sculpture shape space, turning a void into an implied solid. The woman’s torso is defined by the conventional double curves that outline breasts, waist, and hips, but here they shape emptiness. Picasso used a similar strategy to define the body of the guitar in his collage Guitar, Sheet Music and Glass.

Pablo Picasso, Guitar, Sheet Music and Glass, 1912, Collage and charcoal on board, 18 7/8 x 14 3/4 inches (McNay Museum, San Antonio)

Archipenko’s Walking Woman is also reminiscent of the Analytic Cubist strategies used in paintings like Picasso’s Girl with a Mandolin in which simplified, geometric body parts are fragmented and dissolved into the surrounding space. The figure is suggested in Archipenko’s sculpture, and some parts of it, like the head, legs and part of a skirt, can be identified with confidence, but others, like the arms, are missing or only indirectly suggested.

Pablo Picasso, Girl with a Mandolin (Fanny Tellier), 1910, oil on canvas, 39 1/2 x 29 inches (MoMA)

Classical references

Woman Combing Her Hair is much more traditional than Walking Woman despite the shaped void representing the woman’s head and neck. Archipenko used Cubist techniques here to create a decorative form with obvious classical references in both the contrapposto pose and the form. The truncated arm and breaks at the knees suggest the broken remains of Classical figures like the Venus de Milo.

Left: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her Hair, 1915, bronze, 34 7/8 inches tall (Yale University Art Gallery); Right: Aphrodite, known as the “Venus de Milo,” c. 100 B.C. E., marble, 2.02 m. tall (Louvre) (photo: Mattgirling, CC BY 3.0)

A non-naturalistic concavity defines the inner thighs and pubic area, but the effect is still fundamentally naturalistic and sensual. The raised arm merging with the figure’s hair is a quotation of many images of Venus. In this work the innovations of Cubism are used to create a modernist update of a decorative table-top sculpture.

Left: Jacques Lipchitz, Man with a Guitar, 1915, limestone, 38 1/4 x 10 1/2 x 7 3/4 inches (MoMA); Right: Jacques Lipchitz, Man with a Mandolin, 1916-17, limestone, 30 x 10 1/4 x 11 3/8 inches (Yale University Art Gallery)

Jacques Lipchitz also made Cubist figure sculptures in the mid-1910s that participate in the contemporary trend to establish Cubism as a classical style. His Man with a Guitar and Man with a Mandolin abstract the figures into clusters of simple geometric planes. This approach is notably similar to Picasso’s contemporary Cubist figure paintings, such as Seated Man.

Picasso, Seated Man, 1915-16, watercolor on paper, 11 3/8 x 8 7/8 inches (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The technique of stone carving is traditional, and the soft white tones of Lipchitz’s figures reflect the classical tradition of Western sculpture. The figures themselves are radically abstracted, but the overall treatment of the sculptural form remains conventional. Lipchitz emphasizes sculptural mass, rather than integrating mass and space. Man with a Guitar stands on an integrated pedestal, a long-established mode of presentation. Like Archipenko’s more sensual figures of women, Lipchitz’s male musicians turn Cubism into a decorative style with classical overtones.

Cubism instigated two significant developments in twentieth century sculpture. The first, and more radical of the two, was the combination and assemblage of non-traditional materials to create objects that challenged the European sculptural tradition in terms of form, media, and often subject matter. This development led through Dada and Surrealism and on to the many art works of the later 20th century that challenged traditional conceptions of art.

Robert Rauschenberg, Monogram, 1955-59, mixed media (photo: rocor, CC BY-NC 2.0)

The second development of Cubist sculpture was also extremely fertile. It was the establishment of a new abstract formal language for sculpture that retained the traditional Western conception of the art object as designed for aesthetic contemplation, while expanding its range into non-representational forms.

David Smith, Cubi X, 1963, stainless steel, 1308.3 x 199.9 x 61 cm (MoMA) (photo: rocor, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Additional resources:

Read more about Robert Rauschenberg’s Monogram at the Moderna Museet, Stockholm

Read more about David Smith’s Cubi X at the Museum of Modern Art, New York